Request Demo

Are there any biosimilars available for Canakinumab?

7 March 2025

Overview of Canakinumab

Canakinumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically targets interleukin‑1β (IL‑1β). By binding to IL‑1β with high affinity, it prevents this potent pro-inflammatory cytokine from interacting with its receptor. This mechanism is central to its anti‐inflammatory effects, which have been exploited for various indications, particularly in auto-inflammatory disorders. The drug has been developed and marketed by Novartis under the brand name Ilaris, with multiple patents protecting both its composition and its therapeutic uses. Several patents have been issued covering its use in reducing the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with elevated high‑sensitivity C‑reactive protein, as well as for applications in osteoarthritis and other inflammatory conditions.

Mechanism of Action

The primary mechanism of action of canakinumab involves the neutralization of IL‑1β, an important mediator of the inflammatory cascade. By preventing IL‑1β from binding to its receptor, canakinumab effectively dampens the inflammatory signals that contribute to tissue damage and disease progression in auto-inflammatory conditions. This targeted approach allows for precise modulation of the immune response, leading to reduced systemic inflammation without broadly suppressing the immune system. As such, canakinumab stands apart from conventional immunosuppressive therapies, offering a tailored approach that minimizes unwanted side effects. Its high specificity and long half‑life help maintain sustained therapeutic levels with relatively infrequent dosing, making it a valuable option in chronic conditions.

Approved Uses and Indications

Canakinumab is approved for a number of rare auto-inflammatory syndromes, including cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) such as familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome and Muckle–Wells syndrome. In addition, it has been evaluated in conditions beyond these indications; its clinical development has extended into areas such as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), periodic fever syndromes, and even cardiovascular and osteoarthritic complications. Importantly, because canakinumab targets IL‑1β—a key cytokine in many inflammatory processes—it has been investigated in multiple clinical contexts. However, it remains under patent protection as evidenced by the series of patents filed and granted by or on behalf of Novartis. This robust patent estate plays a critical role in the product’s market exclusivity and informs the landscape for potential biosimilar development.

Biosimilars: An Introduction

Biosimilars are biological products that are highly similar to an already licensed reference product in terms of quality attributes, biological activity, safety, and efficacy. They are developed once the original biologic’s data protection has expired or is near expiration and are intended to provide comparable therapeutic benefits at potentially lower costs. The regulatory approval of biosimilars is based on a “totality of the evidence” approach in which extensive analytical, nonclinical, and clinical data demonstrate that any minor differences that may exist do not affect the safety or effectiveness of the biosimilar.

Definition and Regulatory Pathways

The definition of a biosimilar emphasizes similarity rather than identity. Unlike generic drugs for small molecules—where the chemical structure is completely replicated—biosimilars are complex and are produced in living systems, so a small degree of variability is acceptable provided it is clinically insignificant. Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have established comprehensive guidelines to ensure that biosimilars match the reference product’s efficacy, safety, and purity profile through robust comparability exercises. These agencies require a stepwise approach that starts with in‑depth analytical studies to compare structure and function, followed by nonclinical assessments, and then clinical trials—usually with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) endpoints in sensitive populations—to confirm biosimilarity.

Differences between Biosimilars and Generics

While generics are exact chemical copies of their reference products, biosimilars are not identical to their reference biologics. This difference arises because the manufacturing process of biologics involves living cells and proprietary techniques, resulting in inherent variability. Biosimilars must therefore demonstrate a high degree of similarity through extensive analytical characterization, nonclinical safety, and clinical studies. Regulatory agencies allow for minor differences in clinically inactive components provided that these do not translate into any meaningful difference in clinical performance. This is a key departure from the generic paradigm and implies that the pathway for biosimilar approval is more complex and data-intensive.

Current Status of Canakinumab Biosimilars

When considering the question “Are there any biosimilars available for Canakinumab?” it is necessary to review the current landscape in the context of both the clinical evolution of canakinumab and the regulatory environment governing biosimilar approvals.

Market Availability

As of the present time, there are no biosimilars of canakinumab available on the market. Despite canakinumab being an important therapeutic option for rare auto-inflammatory conditions and having a range of clinical indications, the data and published literature—particularly the structured patent documents and pharmaceutics reports prepared by Novartis—do not provide evidence of any competing biosimilar products in the public domain. These patent filings underscore the robust protection of the canakinumab molecule and its associated therapeutic uses, thereby limiting the opportunity for other manufacturers to develop biosimilar versions.

Additionally, reviews and systematic analyses of biosimilar products have detailed numerous products in fields such as oncology, inflammatory diseases, and supportive care. However, canakinumab is notably absent from the list of biosimilars that have reached the market or are in late-stage clinical development. The absence of any publicly available references or clinical trial results discussing a biosimilar for canakinumab suggests that biosimilar development in this context has not yet emerged into the market. The reason for this situation is multifaceted: canakinumab is relatively recent compared to earlier biologics that have seen multiple biosimilar candidates, and extensive patent protection maintained by Novartis further inhibits biosimilar competition.

Development and Approval Process

The development pathway for a biosimilar is complex and is generally initiated once the reference product’s patent exclusivity is close to expiry or after sufficient data protection has been achieved. For canakinumab, a series of patents—covering both the product and its therapeutic applications—have been filed as recently as 2018 and even projected into future dates. These patents not only address the composition of the molecule but also its use in several indications, such as cardiovascular risk reduction and osteoarthritis. Given this robust intellectual property landscape, potential biosimilar developers face high barriers to entry.

Furthermore, the development of a biosimilar for a monoclonal antibody requires precise and extensive analytical comparison studies. The totality of evidence necessitates showing that the candidate product is highly similar to the originator canakinumab in terms of molecular structure, post‑translational modifications (such as glycosylation), binding affinity to IL‑1β, downstream biological activity, and clinical performance in sensitive patient populations. While many biosimilars for other monoclonal antibodies (e.g., for adalimumab, infliximab, rituximab, trastuzumab) have successfully navigated this pathway, there exists no published data or press releases indicating that any sponsor has succeeded in developing and obtaining regulatory approval for a canakinumab biosimilar.

The absence of any such information in reliable databases such as Synapse—the source of many of our references—strongly suggests that no biosimilar canakinumab has reached a sufficiently advanced stage of development or regulatory submission to warrant market entry. Companies typically announce their biosimilar candidates once they enter confirmatory phase III trials or have received a positive regulatory opinion; however, there are no announcements or clinical trial registry entries indicating that a canakinumab biosimilar is under late‐stage development.

Impact and Implications

The introduction of biosimilars into the market generally offers several benefits including reduced healthcare costs, improved patient access, and increased competition among pharmaceutical manufacturers. These impacts can be profound in fields like oncology and auto-inflammatory diseases, where biologics are expensive. Although canakinumab itself is a high‑cost biologic with important therapeutic uses, there is currently no biosimilar alternative available, which has meaningful clinical and economic implications.

Clinical and Economic Impact

Clinically, the absence of biosimilars for canakinumab means that patients and healthcare providers have only one therapeutic option from Novartis with proven efficacy and safety data. This lack of competition could lead to higher costs for patients and payers. In contrast, other drug classes have seen cost reductions following the market entry of biosimilars. For instance, biosimilars in the oncology space, such as rituximab or trastuzumab biosimilars, have encouraged price competition and increased patient access. The economic burden of canakinumab is therefore carried solely by the innovator product, which may result in limited prescribing flexibility and potential budget constraints for healthcare systems aiming to treat rare auto-inflammatory diseases.

From an economic perspective, the introduction of biosimilars generally spurs downward pressure on drug pricing. Several studies have documented cost savings once biosimilars enter the market—savings that can be significant when managing chronic and high‑cost conditions. However, due to the robust patent protection and the low likelihood of biosimilar competition for canakinumab in the near term, the cost‐benefit advantages seen with other biologics may not be realized for canakinumab patients. The lack of biosimilars may limit the overall market competition and thus maintain higher pricing, which could impact both payer reimbursement decisions and the degree of patient access in cost‐constrained environments.

Future Prospects for Canakinumab Biosimilars

Looking forward, the development of biosimilars for canakinumab could become a possibility once the current patent protections begin to expire or if legal challenges or licensing agreements alter the exclusivity landscape. Although there is currently no evidence of any biosimilar canakinumab in development, future advances in biotechnological manufacturing, regulatory science, and intellectual property law might pave the way for other companies to engage in biosimilar research for canakinumab.

The pathway to approving a biosimilar for a complex monoclonal antibody like canakinumab will require a comprehensive demonstration of analytical similarity, robust nonclinical characterizations, and tailored clinical trials. Such development programs will likely take several years and require significant investment owing to the complexity of the molecule and the need to navigate a well‑protected patent landscape. Furthermore, if any candidate is developed in the future, the regulatory process would mirror that of other biosimilars, relying on the “totality of evidence” approach to conclude that any minor differences are not clinically meaningful.

Should a canakinumab biosimilar eventually enter the market, its approval could have substantial implications on both clinical practice and healthcare economics. Clinicians might have additional therapeutic options to tailor treatment plans based on patient-specific factors. Economically, increased competition could drive down the price of canakinumab, improving patient access and potentially freeing up budgetary resources for other therapies—an outcome that has been seen in other therapeutic areas following biosimilar entry. Additionally, a biosimilar for canakinumab would also stimulate innovation in the manufacturing and evaluation of complex monoclonal antibodies, potentially leading to the development of “biosimilar next‐generation” products with further improved characteristics or even extended indications.

Conclusion

In summary, canakinumab is a highly specific IL‑1β inhibitor with established efficacy in rare auto-inflammatory conditions and other inflammatory indications. Its mechanism of action, characterized by targeted blockade of IL‑1β, underpins its clinical applications and has been rigorously supported by multiple patents and clinical studies. Biosimilars, defined as products that are highly similar to a licensed reference product without clinically meaningful differences, have emerged in many therapeutic areas to offer comparable efficacy and safety at lower costs. However, unlike other biologics where several biosimilar products have already reached the market (such as for adalimumab, infliximab, and rituximab), there is currently no evidence from Synapse-reliable sources or published literature of any biosimilar for canakinumab being available or in late-stage development.

The robust and extensive patent protection maintained by Novartis, covering both the composition and several therapeutic applications of canakinumab, represents a significant barrier to biosimilar development. Furthermore, given the complexity of melan monoclonal antibodies and the rigorous regulatory requirements needed to prove biosimilarity, potential biosimilar candidates for canakinumab have not yet emerged in the market. This situation has important clinical and economic implications—patients and healthcare providers remain dependent on the innovator product, which in turn may maintain higher drug costs and limit treatment flexibility.

Looking towards the future, the potential for a canakinumab biosimilar exists once patent exclusivity diminishes or innovative development strategies overcome current barriers. Should such a biosimilar be developed, it would likely follow a similar regulatory pathway as other biosimilars, undergoing extensive analytical, nonclinical, and clinical comparability studies to ensure that any observed differences do not compromise efficacy or safety. Ultimately, the introduction of a biosimilar for canakinumab would have a positive impact by enhancing market competition, reducing treatment costs, and expanding patient access to vital biologic therapies.

In conclusion, based on the available references from synapse and related sources, there are currently no biosimilars available for canakinumab in the global market. The robust patent protections, coupled with the complexities inherent in developing biosimilars for a monoclonal antibody like canakinumab, have precluded the entry of alternative products. The future, however, may hold promise as biosimilar development continues to evolve alongside changes in regulatory policies and patent landscapes. Until then, canakinumab remains a singular, innovator product used in the management of specific inflammatory and auto-inflammatory diseases, with its clinical and economic impact closely tied to its proprietary status and associated market dynamics.

Canakinumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically targets interleukin‑1β (IL‑1β). By binding to IL‑1β with high affinity, it prevents this potent pro-inflammatory cytokine from interacting with its receptor. This mechanism is central to its anti‐inflammatory effects, which have been exploited for various indications, particularly in auto-inflammatory disorders. The drug has been developed and marketed by Novartis under the brand name Ilaris, with multiple patents protecting both its composition and its therapeutic uses. Several patents have been issued covering its use in reducing the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with elevated high‑sensitivity C‑reactive protein, as well as for applications in osteoarthritis and other inflammatory conditions.

Mechanism of Action

The primary mechanism of action of canakinumab involves the neutralization of IL‑1β, an important mediator of the inflammatory cascade. By preventing IL‑1β from binding to its receptor, canakinumab effectively dampens the inflammatory signals that contribute to tissue damage and disease progression in auto-inflammatory conditions. This targeted approach allows for precise modulation of the immune response, leading to reduced systemic inflammation without broadly suppressing the immune system. As such, canakinumab stands apart from conventional immunosuppressive therapies, offering a tailored approach that minimizes unwanted side effects. Its high specificity and long half‑life help maintain sustained therapeutic levels with relatively infrequent dosing, making it a valuable option in chronic conditions.

Approved Uses and Indications

Canakinumab is approved for a number of rare auto-inflammatory syndromes, including cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) such as familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome and Muckle–Wells syndrome. In addition, it has been evaluated in conditions beyond these indications; its clinical development has extended into areas such as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), periodic fever syndromes, and even cardiovascular and osteoarthritic complications. Importantly, because canakinumab targets IL‑1β—a key cytokine in many inflammatory processes—it has been investigated in multiple clinical contexts. However, it remains under patent protection as evidenced by the series of patents filed and granted by or on behalf of Novartis. This robust patent estate plays a critical role in the product’s market exclusivity and informs the landscape for potential biosimilar development.

Biosimilars: An Introduction

Biosimilars are biological products that are highly similar to an already licensed reference product in terms of quality attributes, biological activity, safety, and efficacy. They are developed once the original biologic’s data protection has expired or is near expiration and are intended to provide comparable therapeutic benefits at potentially lower costs. The regulatory approval of biosimilars is based on a “totality of the evidence” approach in which extensive analytical, nonclinical, and clinical data demonstrate that any minor differences that may exist do not affect the safety or effectiveness of the biosimilar.

Definition and Regulatory Pathways

The definition of a biosimilar emphasizes similarity rather than identity. Unlike generic drugs for small molecules—where the chemical structure is completely replicated—biosimilars are complex and are produced in living systems, so a small degree of variability is acceptable provided it is clinically insignificant. Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have established comprehensive guidelines to ensure that biosimilars match the reference product’s efficacy, safety, and purity profile through robust comparability exercises. These agencies require a stepwise approach that starts with in‑depth analytical studies to compare structure and function, followed by nonclinical assessments, and then clinical trials—usually with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) endpoints in sensitive populations—to confirm biosimilarity.

Differences between Biosimilars and Generics

While generics are exact chemical copies of their reference products, biosimilars are not identical to their reference biologics. This difference arises because the manufacturing process of biologics involves living cells and proprietary techniques, resulting in inherent variability. Biosimilars must therefore demonstrate a high degree of similarity through extensive analytical characterization, nonclinical safety, and clinical studies. Regulatory agencies allow for minor differences in clinically inactive components provided that these do not translate into any meaningful difference in clinical performance. This is a key departure from the generic paradigm and implies that the pathway for biosimilar approval is more complex and data-intensive.

Current Status of Canakinumab Biosimilars

When considering the question “Are there any biosimilars available for Canakinumab?” it is necessary to review the current landscape in the context of both the clinical evolution of canakinumab and the regulatory environment governing biosimilar approvals.

Market Availability

As of the present time, there are no biosimilars of canakinumab available on the market. Despite canakinumab being an important therapeutic option for rare auto-inflammatory conditions and having a range of clinical indications, the data and published literature—particularly the structured patent documents and pharmaceutics reports prepared by Novartis—do not provide evidence of any competing biosimilar products in the public domain. These patent filings underscore the robust protection of the canakinumab molecule and its associated therapeutic uses, thereby limiting the opportunity for other manufacturers to develop biosimilar versions.

Additionally, reviews and systematic analyses of biosimilar products have detailed numerous products in fields such as oncology, inflammatory diseases, and supportive care. However, canakinumab is notably absent from the list of biosimilars that have reached the market or are in late-stage clinical development. The absence of any publicly available references or clinical trial results discussing a biosimilar for canakinumab suggests that biosimilar development in this context has not yet emerged into the market. The reason for this situation is multifaceted: canakinumab is relatively recent compared to earlier biologics that have seen multiple biosimilar candidates, and extensive patent protection maintained by Novartis further inhibits biosimilar competition.

Development and Approval Process

The development pathway for a biosimilar is complex and is generally initiated once the reference product’s patent exclusivity is close to expiry or after sufficient data protection has been achieved. For canakinumab, a series of patents—covering both the product and its therapeutic applications—have been filed as recently as 2018 and even projected into future dates. These patents not only address the composition of the molecule but also its use in several indications, such as cardiovascular risk reduction and osteoarthritis. Given this robust intellectual property landscape, potential biosimilar developers face high barriers to entry.

Furthermore, the development of a biosimilar for a monoclonal antibody requires precise and extensive analytical comparison studies. The totality of evidence necessitates showing that the candidate product is highly similar to the originator canakinumab in terms of molecular structure, post‑translational modifications (such as glycosylation), binding affinity to IL‑1β, downstream biological activity, and clinical performance in sensitive patient populations. While many biosimilars for other monoclonal antibodies (e.g., for adalimumab, infliximab, rituximab, trastuzumab) have successfully navigated this pathway, there exists no published data or press releases indicating that any sponsor has succeeded in developing and obtaining regulatory approval for a canakinumab biosimilar.

The absence of any such information in reliable databases such as Synapse—the source of many of our references—strongly suggests that no biosimilar canakinumab has reached a sufficiently advanced stage of development or regulatory submission to warrant market entry. Companies typically announce their biosimilar candidates once they enter confirmatory phase III trials or have received a positive regulatory opinion; however, there are no announcements or clinical trial registry entries indicating that a canakinumab biosimilar is under late‐stage development.

Impact and Implications

The introduction of biosimilars into the market generally offers several benefits including reduced healthcare costs, improved patient access, and increased competition among pharmaceutical manufacturers. These impacts can be profound in fields like oncology and auto-inflammatory diseases, where biologics are expensive. Although canakinumab itself is a high‑cost biologic with important therapeutic uses, there is currently no biosimilar alternative available, which has meaningful clinical and economic implications.

Clinical and Economic Impact

Clinically, the absence of biosimilars for canakinumab means that patients and healthcare providers have only one therapeutic option from Novartis with proven efficacy and safety data. This lack of competition could lead to higher costs for patients and payers. In contrast, other drug classes have seen cost reductions following the market entry of biosimilars. For instance, biosimilars in the oncology space, such as rituximab or trastuzumab biosimilars, have encouraged price competition and increased patient access. The economic burden of canakinumab is therefore carried solely by the innovator product, which may result in limited prescribing flexibility and potential budget constraints for healthcare systems aiming to treat rare auto-inflammatory diseases.

From an economic perspective, the introduction of biosimilars generally spurs downward pressure on drug pricing. Several studies have documented cost savings once biosimilars enter the market—savings that can be significant when managing chronic and high‑cost conditions. However, due to the robust patent protection and the low likelihood of biosimilar competition for canakinumab in the near term, the cost‐benefit advantages seen with other biologics may not be realized for canakinumab patients. The lack of biosimilars may limit the overall market competition and thus maintain higher pricing, which could impact both payer reimbursement decisions and the degree of patient access in cost‐constrained environments.

Future Prospects for Canakinumab Biosimilars

Looking forward, the development of biosimilars for canakinumab could become a possibility once the current patent protections begin to expire or if legal challenges or licensing agreements alter the exclusivity landscape. Although there is currently no evidence of any biosimilar canakinumab in development, future advances in biotechnological manufacturing, regulatory science, and intellectual property law might pave the way for other companies to engage in biosimilar research for canakinumab.

The pathway to approving a biosimilar for a complex monoclonal antibody like canakinumab will require a comprehensive demonstration of analytical similarity, robust nonclinical characterizations, and tailored clinical trials. Such development programs will likely take several years and require significant investment owing to the complexity of the molecule and the need to navigate a well‑protected patent landscape. Furthermore, if any candidate is developed in the future, the regulatory process would mirror that of other biosimilars, relying on the “totality of evidence” approach to conclude that any minor differences are not clinically meaningful.

Should a canakinumab biosimilar eventually enter the market, its approval could have substantial implications on both clinical practice and healthcare economics. Clinicians might have additional therapeutic options to tailor treatment plans based on patient-specific factors. Economically, increased competition could drive down the price of canakinumab, improving patient access and potentially freeing up budgetary resources for other therapies—an outcome that has been seen in other therapeutic areas following biosimilar entry. Additionally, a biosimilar for canakinumab would also stimulate innovation in the manufacturing and evaluation of complex monoclonal antibodies, potentially leading to the development of “biosimilar next‐generation” products with further improved characteristics or even extended indications.

Conclusion

In summary, canakinumab is a highly specific IL‑1β inhibitor with established efficacy in rare auto-inflammatory conditions and other inflammatory indications. Its mechanism of action, characterized by targeted blockade of IL‑1β, underpins its clinical applications and has been rigorously supported by multiple patents and clinical studies. Biosimilars, defined as products that are highly similar to a licensed reference product without clinically meaningful differences, have emerged in many therapeutic areas to offer comparable efficacy and safety at lower costs. However, unlike other biologics where several biosimilar products have already reached the market (such as for adalimumab, infliximab, and rituximab), there is currently no evidence from Synapse-reliable sources or published literature of any biosimilar for canakinumab being available or in late-stage development.

The robust and extensive patent protection maintained by Novartis, covering both the composition and several therapeutic applications of canakinumab, represents a significant barrier to biosimilar development. Furthermore, given the complexity of melan monoclonal antibodies and the rigorous regulatory requirements needed to prove biosimilarity, potential biosimilar candidates for canakinumab have not yet emerged in the market. This situation has important clinical and economic implications—patients and healthcare providers remain dependent on the innovator product, which in turn may maintain higher drug costs and limit treatment flexibility.

Looking towards the future, the potential for a canakinumab biosimilar exists once patent exclusivity diminishes or innovative development strategies overcome current barriers. Should such a biosimilar be developed, it would likely follow a similar regulatory pathway as other biosimilars, undergoing extensive analytical, nonclinical, and clinical comparability studies to ensure that any observed differences do not compromise efficacy or safety. Ultimately, the introduction of a biosimilar for canakinumab would have a positive impact by enhancing market competition, reducing treatment costs, and expanding patient access to vital biologic therapies.

In conclusion, based on the available references from synapse and related sources, there are currently no biosimilars available for canakinumab in the global market. The robust patent protections, coupled with the complexities inherent in developing biosimilars for a monoclonal antibody like canakinumab, have precluded the entry of alternative products. The future, however, may hold promise as biosimilar development continues to evolve alongside changes in regulatory policies and patent landscapes. Until then, canakinumab remains a singular, innovator product used in the management of specific inflammatory and auto-inflammatory diseases, with its clinical and economic impact closely tied to its proprietary status and associated market dynamics.

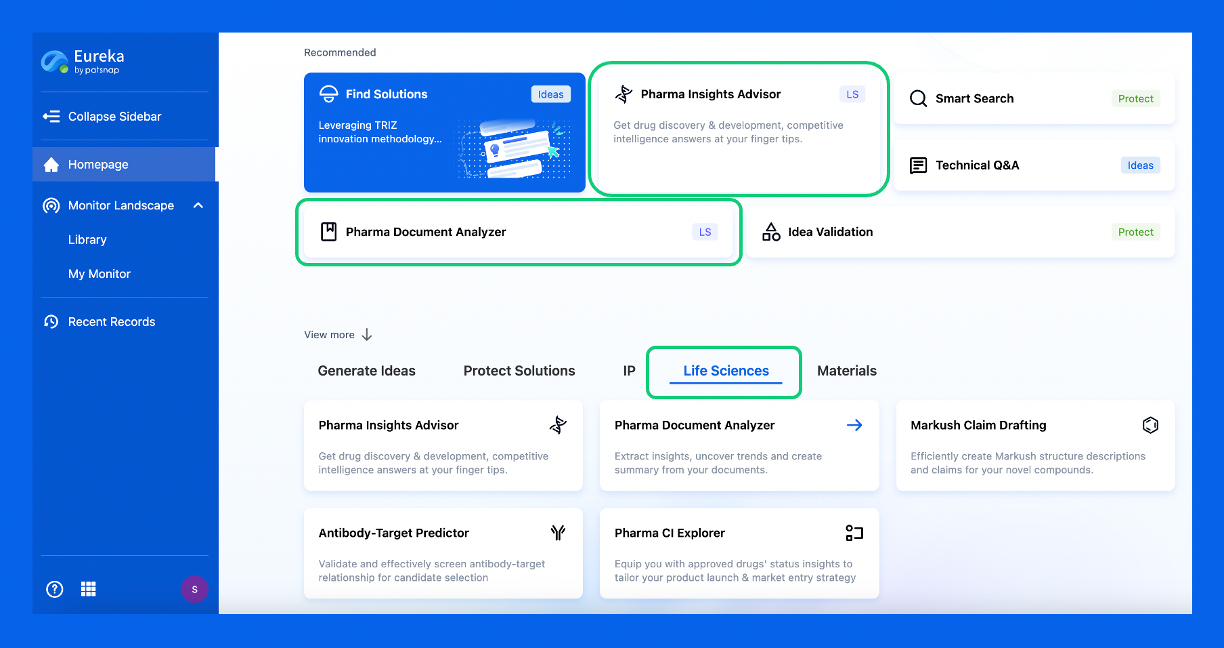

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.