Are there any biosimilars available for Peginterferon?

Introduction to Peginterferon

Peginterferon refers to interferon molecules that have been chemically modified through attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG) moieties. This pegylation process helps improve the pharmacokinetic profile by prolonging the half‐life of the interferon in circulation and reducing the frequency of dosing. Clinically, peginterferon is primarily used in the treatment of chronic viral infections such as hepatitis C and hepatitis B, as well as certain malignancies and other diseases with an immunomodulatory or antiviral component. Studies conducted in diverse patient populations, such as the one performed in Iranian patients with chronic hepatitis C, highlight that peginterferon alfa‐2a and peginterferon alfa‐2b are both effective therapeutic agents albeit with some differences in tolerability and side effect profiles.

Mechanism of Action

The underlying mechanism of action of peginterferon is driven by its ability to initiate a cascade of intracellular events that culminate in an enhanced antiviral and immunomodulatory state. Upon binding to specific interferon receptors on cell surfaces, peginterferon activates a series of signal transduction pathways that modulate the expression of interferon-stimulated genes. This activity results in antiviral responses, inhibition of viral replication, and modulation of the immune system so that it can effectively clear the pathogen. The pegylation does not alter the inherent biological activity of the protein; rather, it optimizes its bioavailability and stability by creating a molecule that circulates longer than its unmodified counterpart.

Overview of Biosimilars

Definition and Importance

Biosimilars are biologic products that are demonstrated, through a rigorous analytical and clinical comparability exercise, to be highly similar to an already approved reference (or originator) biologic drug. It is important to note that, due to the inherent complexity and the nature of biological production processes in living systems, biosimilars are not exact copies of the reference product; they are “highly similar” with no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency. The importance of biosimilars in modern healthcare lies in their potential to provide more cost‐effective alternatives, thereby expanding patient access to therapies that were once limited due to high costs. Regulatory agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have established stringent guidelines and approval pathways that ensure that biosimilars meet the high standards required for use in clinical settings.

Regulatory Pathways

The regulatory framework for biosimilars is designed around the “totality of evidence” approach, which requires that manufacturers demonstrate comparability through analytical assessments, nonclinical studies, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluations, and ultimately clinical trials. This stepwise process begins with a detailed physicochemical characterization to demonstrate that the biosimilar is highly similar to the reference product. It is followed by nonclinical evaluations—often to assess bioactivity and immunogenic potential—and finally clinical studies to confirm similarity in efficacy and safety. Regulatory authorities worldwide have adopted these rigorous processes to instill confidence in both healthcare providers and patients regarding the use of biosimilars. Although the manufacturing and regulatory challenges can be significant, the end benefit is a more competitive market that reduces overall healthcare expenditures.

Peginterferon Biosimilars

Current Market Availability

When it comes to peginterferon specifically, the available peer-reviewed and industry literature—particularly the studies available from the Synapse source—primarily focus on the comparison and clinical characterization of different peginterferon formulations, such as peginterferon alfa‐2a versus peginterferon alfa‐2b. These studies demonstrate that there are formulation differences that appear related to the size and shape of the attached PEG moiety or differences in the covalent attachment method. For example, peginterferon alfa‐2a typically possesses a branched 40 kDa PEG chain bound to lysine residues, whereas peginterferon alfa‐2b generally carries a linear 12 kDa PEG chain attached via more labile bonds. These differences, however, are variations within the approved reference products rather than examples of a biosimilar evaluation where a manufacturer develops a competing product that is highly similar to a marketed originator.

From the current literature provided, there is no explicit reference or indication that a biosimilar version of peginterferon has been developed and approved as a distinct product. Unlike other biologics—such as monoclonal antibodies, granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors where clear biosimilars have become available—the field of peginterferon appears to be represented by the originator products that have undergone variations (for instance, different pegylation strategies) to optimize clinical performance rather than independent biosimilar entrants. Some studies have even explored novel pegylated interferon formulations, such as a novel pegylated recombinant consensus interferon‐α variant compared with peginterferon‐α‐2a, primarily to evaluate whether such modifications can further improve pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles. While these investigations are highly valuable from a research and development standpoint, they do not constitute the full biosimilar development paradigm as defined by regulatory agencies—where the product is intentionally designed to match the reference product’s key attributes for a cost‐efficient alternative.

Thus, in the current state of the market, based on the Synapse source materials, there is no clear evidence or published information that any biosimilars for peginterferon (i.e. biosimilar counterparts intended to be alternatives to established peginterferon products) have achieved regulatory approval or are commercially available. Rather, the discussions in the literature focus on the comparison and clinical outcomes tied to products from the innovator companies that have optimized their own peginterferon formulations over time.

Regulatory Approvals

The regulatory approvals in the biosimilar field have mostly been revolutionizing for other classes of biologics. For example, approvals have been granted for biosimilars of filgrastim, monoclonal antibodies, and other therapeutic proteins which have clearly defined equivalence studies and multiple reference products from the innovator companies. In the case of peginterferon products, however, no regulatory pathway has yet been exploited for a biosimilar version that is distinct from the originator’s differentiated formulations. Regulatory agencies require comprehensive comparability studies—spanning analytical characterization, clinical efficacy, and immunogenicity assessments—to determine biosimilarity. Given that the available studies on peginterferon focus on either the differentiation between peginterferon alfa‐2a and peginterferon alfa‐2b or explore novel pegylated interferon variants, these are viewed as enhancements or variations within the same therapeutic category rather than a second, independent biosimilar product line.

While the global regulatory environment for biosimilars is robust and has clearly led to several approvals in other therapeutic segments, there are no published Synapse materials that document a complete biosimilar program for peginterferon. Consequently, there is no current evidence to suggest that any peginterferon biosimilars have been submitted for or received regulatory approval under the specific biosimilar pathways established by agencies such as the FDA or EMA.

Market Dynamics and Future Prospects

Market Trends and Challenges

The global biosimilars market has been characterized by exponential growth and clinical integration for several therapeutic areas. Innovations in reducing manufacturing complexities and robust clinical programs have resulted in multiple biosimilar approvals, which in turn have enforced market competition, reduced drug costs, and substantially improved patient access for treatments such as for oncology and autoimmune diseases. However, this dynamic is heavily dependent on several factors—patent expirations, manufacturing complexities, and robust clinical trial processes.

In the context of peginterferon, the current market dynamic is somewhat different. Peginterferon products have primarily been developed as part of the originator’s portfolio through incremental innovation via modification of PEG conjugation techniques. While the successful introduction of peginterferon products such as peginterferon alfa‐2a and peginterferon alfa‐2b has contributed to substantial clinical data backing their efficacy, the clinical landscape for hepatitis C in particular has evolved rapidly with the advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) that often offer superior efficacy and safety profiles. Consequently, there may be less competitive pressure or commercial incentive for developing biosimilar alternatives for peginterferon, as the clinical need might be shifting towards newer treatment modalities.

Furthermore, even if the patent environment allowed for biosimilar development in this area, manufacturers would have to contend with lengthy and resource-intensive biosimilar development programs. They would need to demonstrate, through detailed analytical and clinical comparability studies, that their version of peginterferon is highly similar to the reference product. No Synapse reference to such a biosimilar pathway for peginterferon exists to date, suggesting that market forces may currently not favor—or might be diverting R&D resources away from—such development endeavors.

Future Developments and Research

Looking forward, there are multiple factors that could potentially influence the future development of biosimilars in the peginterferon space. First, a paradigm shift in certain clinical indications, such as the treatment of emerging viral diseases (for instance, in response to pandemics or novel viral outbreaks), could rejuvenate interest in interferon-based therapies. An example is the investigational use of peginterferon lambda in COVID-19, which demonstrated that interferon formulations can be repurposed for new therapeutic challenges. In such a scenario, if a robust clinical need arises and if peginterferon-based therapies retain clinical importance, it may incentivize biopharmaceutical companies to explore biosimilar development for peginterferon formulations.

Secondly, technological advancements in bioprocessing and analytical characterization can reduce the costs and complexities involved in biosimilar development. As manufacturing processes become more efficient and cost-effective, more companies might consider exploring the biosimilar route for peginterferon, especially if regulatory agencies further refine guidance based on accumulated experience with other biosimilars. Additionally, emerging research that focuses on improved pharmacodynamic markers or novel methods for demonstrating immunogenicity and safety could potentially pave the way for streamlined clinical programs. However, these developments would also need to balance local clinical needs and market size considerations. For instance, the chronic hepatitis C market, once a major driver for peginterferon use, has transformed significantly in recent years due to newer direct-acting antivirals. This change in demand may reduce the immediate incentive for competing biosimilars in this specific area.

Moreover, from a global market dynamics perspective, emerging markets could potentially offer an avenue where cost pressure is higher, and where healthcare systems might benefit significantly from biosimilar alternatives. The experience from other therapeutic classes—where biosimilars have led to markedly lower drug acquisition costs—suggests that if peginterferon biosimilars were to be developed, they could play a crucial role in expanding therapeutic access in resource-limited settings. Yet, to date, no Synapse references explicitly document a biosimilar for peginterferon, indicating that at this moment, any potential biosimilar candidates are either in early development stages or not being actively pursued compared to other high-profile biosimilar programs.

Another research perspective involves the potential repurposing of peginterferon compounds owing to their unique immunomodulatory properties. Recent studies have compared novel pegylated recombinant consensus interferon variants with established peginterferon alfa products. Although these investigations are not denoted as biosimilar programs per se, they underscore the continuous innovation that occurs in the peginterferon domain. They might eventually stimulate interest in developing a product portfolio that combines both originator and biosimilar strategies if market conditions change. Advances in molecular characterization techniques, such as high-performance liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, circular dichroism, and various bioassays, all of which are crucial in biosimilar comparability exercises, continue to strengthen the reliability of similarity determinations. Such technological improvements, together with harmonized global regulatory requirements, could eventually reduce the barriers to entry for peginterferon biosimilars.

Furthermore, the scientific community is actively engaged in discussions about biosimilar acceptance. The conversations range from how to measure clinical performance to the impact of even minor modifications on properties such as immunogenicity and overall pharmacodynamics. These discussions are vital in shaping future regulatory policies and could have a positive influence on biosimilar development in less explored targets like peginterferon. In addition, educational initiatives aimed at organizing and disseminating research findings among clinicians and healthcare administrators have been a hallmark of successful biosimilar uptake in other areas. Similar approaches could be applied if any peginterferon biosimilars were to be developed, ensuring that both providers and patients are fully informed of the comparable safety and efficacy profiles of these products relative to the reference products.

Conclusion

In summary, peginterferon represents a uniquely modified interferon molecule that has improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic attributes due to pegylation. It is widely used in treating chronic viral infections like hepatitis C and hepatitis B, thanks to its ability to enhance antiviral activity and modulate immune responses. Biosimilars, on the other hand, are biologic products that are highly similar to their reference products and have become important therapeutic alternatives in various areas by lowering costs and expanding patient access.

When it comes to the specific question of whether there are any biosimilars available for peginterferon, the detailed review of the Synapse-sourced literature reveals that the focus has instead been on optimizing and comparing originator formulations—such as the differences seen between peginterferon alfa‐2a and peginterferon alfa‐2b—and on evaluating novel pegylated interferon variants. There is no clear indication from the available references that a dedicated biosimilar version of peginterferon has been developed or approved through the rigorous biosimilar pathways established by regulatory authorities like the FDA or EMA. This lack of biosimilar products in the peginterferon space may be partly due to evolving treatment landscapes (for example, the rise of direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C) and the substantial R&D investments required to develop a biosimilar for a molecule already optimized by the originator.

From a market dynamics perspective, while many biosimilars for other biologics have established competitive positions in their respective markets, peginterferon remains in a niche where originator products dominate and are continually optimized. Nonetheless, future developments could alter this scenario if new clinical needs arise—such as repurposing interferon-based therapies for emerging diseases—or if advancements in manufacturing and regulatory science lower the hurdles for biosimilar development in this space. Additionally, emerging markets with significant cost pressures might provide the impetus for companies to eventually consider entering the peginterferon biosimilar space.

In conclusion, based on the Synapse references provided, there are no marketed biosimilars available specifically for peginterferon at present. The available literature concentrates on comparing different peginterferon products and evaluating novel formulations rather than on true biosimilar development. While the overall biosimilar market has been rapidly expanding in many other therapeutic areas, the unique clinical, commercial, and regulatory dynamics of peginterferon have so far not led to the emergence of biosimilar products for this specific compound. Future research, market shifts, and technological advancements, however, may well create opportunities for biosimilar developments in this space, but as of now, peginterferon biosimilars remain an area of potential rather than an existing reality.

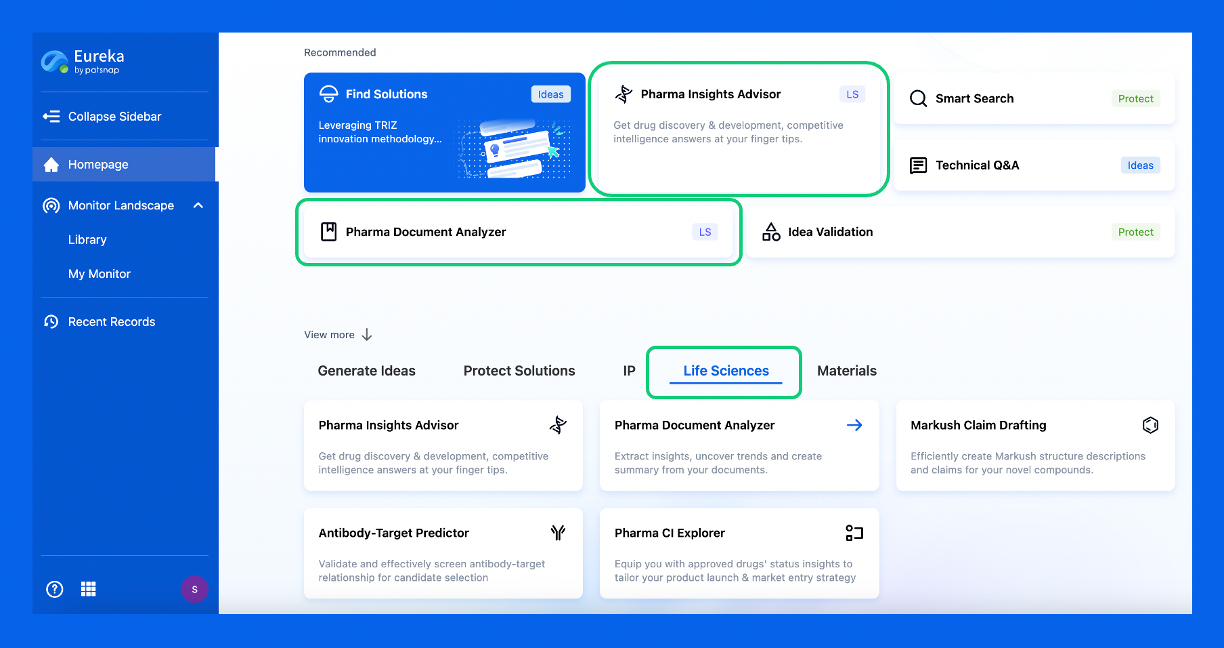

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.