How do different drug classes work in treating Dry Eye Syndromes?

Overview of Dry Eye Syndromes

Dry eye syndrome (DES) is a multifactorial, chronic disorder affecting the ocular surface and tear film. It is characterized by unstable or deficient tear production, which leads to discomfort, visual disturbances, and potential damage to the corneal and conjunctival epithelium. Patients often experience a constellation of symptoms that include dryness, burning, stinging, itching, foreign body sensation, photophobia, and episodes of blurred vision. In more severe cases, the ocular surface may sustain damage that can impinge on visual functions and overall quality of life. Importantly, the signs and symptoms observed in DES can vary considerably among patients, and the intensity may not always correspond directly to the clinical findings observed during a detailed ophthalmic evaluation.

Causes and Risk Factors

Multiple factors contribute to the development and progression of dry eye disease. The etiologies are multifaceted and can be broadly divided into aqueous-deficient and evaporative forms, with a considerable number of patients showing a mix of both mechanisms. Aqueous deficiency may result from lacrimal gland dysfunction, as seen in conditions like Sjögren’s syndrome and age-related atrophy of the lacrimal gland, while evaporative dry eye is often linked to meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), which leads to an abnormal lipid layer and increased tear evaporation. Additional risk factors include aging, female gender, extended screen time, environmental factors (such as low humidity or high pollution), contact lens use, certain systemic medications (antihistamines, antihypertensives, and antidepressants), and autoimmune disorders. The complex interplay of these factors triggers an inflammatory cascade on the ocular surface, perpetuating a “vicious cycle” that exacerbates the tear film instability and surface damage.

Drug Classes Used in Treating Dry Eye Syndromes

Treating dry eye syndrome requires a multi-pronged approach because of its multifactorial pathology. The primary therapeutic options include the use of lubricating and moisturizing agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, and immunomodulatory agents. Each drug class targets distinct elements in the pathogenesis of the disease, offering relief either by supplementing the tear film directly, reducing inflammation, or modulating the underlying immune response.

Lubricating and Moisturizing Agents

Lubricating and moisturizing agents are the first line of treatment for patients with mild to moderate dry eye disease. These agents, commonly referred to as artificial tears or tear substitutes, are formulated to temporarily replenish the tear film and relieve ocular discomfort. They often consist of aqueous solutions containing polymers (cellulose derivatives like carboxymethylcellulose and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose) that not only add volume but also enhance retention time on the ocular surface. Moreover, some formulations include lipids or lipid-containing emulsions that provide a supplementary lipid layer to reduce evaporation in cases where the tear film’s lipid component is insufficient. In addition to viscosity-enhancing polymers, certain tear substitutes may include components like hyaluronic acid, known for its hydrating properties and biocompatibility, and even naturally derived extracts that may offer additional antioxidant protection.

Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Because inflammation plays a central role in dry eye’s pathogenesis, anti-inflammatory drugs are a cornerstone of treatment, especially in moderate to severe cases. The inflammatory process in DES involves increased expression of inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), leading to epithelial damage and a further decline in tear film quality. Topical corticosteroids, such as loteprednol etabonate, dexamethasone, and fluorometholone, are often used as pulse therapy to rapidly reduce inflammation and cytokine production on the ocular surface. However, due to the potential side effects associated with chronic corticosteroid use (increased intraocular pressure, cataract formation), their use is generally limited to short-term courses.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tetracycline derivatives (e.g., doxycycline) have also been employed for their anti-inflammatory effects. Tetracycline derivatives not only provide anti-inflammatory benefits but also help manage MGD by reducing bacterial colonization and modulating lipid secretion by meibomian glands. These medications ultimately help to decrease the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as MMP-9, and restore ocular surface homeostasis.

Immunomodulatory Agents

Immunomodulatory agents represent a more targeted treatment strategy that addresses the underlying immune-mediated inflammation in DES. Cyclosporine A (CsA) is perhaps the best-known immunomodulatory drug in the context of dry eye. It works by inhibiting T-cell activation and reducing the release of inflammatory cytokines from ocular surface cells. Commercial formulations of topical CsA, such as Restasis, have been approved by the FDA and are widely used for patients whose condition does not respond adequately to lubricating agents alone.

More recently, newer immunomodulatory therapies have been developed, including compounds such as lifitegrast, an LFA-1 antagonist that interferes with T-cell adhesion and migration, and other emerging small molecules that target specific components of the inflammatory cascade. These agents actively modulate the immune response, thereby reducing chronic ocular surface inflammation and promoting the restoration of a healthier tear film and ocular surface environment.

Mechanisms of Action

Understanding the mechanisms by which these drug classes work is critical for appreciating the rationale behind their use in treating dry eye syndrome. Each class employs a distinct strategy to restore tear film stability, reduce inflammation, and alleviate ocular discomfort.

Mechanism of Lubricating Agents

Lubricating agents primarily act by physically supplementing the deficient tear film, thereby enhancing ocular surface hydration and reducing friction during blinking. The artificial tears contain polymers—such as CMC, HPMC, and hyaluronic acid—that mimic the viscosity of natural tears. These polymers increase the lubrication of the corneal and conjunctival surface and stabilize the tear film, which in turn helps to dilute and flush away inflammatory cytokines that accumulate on the ocular surface.

Many formulations have been optimized to target different aspects of dry eye pathology. For instance, solutions enriched with hyaluronic acid not only provide viscous lubrication but also promote epithelial healing and reduce osmolarity fluctuations—a key factor in triggering inflammatory cascades. Lipid-containing formulations are designed to restore the lipid layer of the tear film, thereby reducing tear evaporation and improving tear film stability. Some natural extracts and osmoprotectants have also been incorporated into these solutions to modulate cell volume and protect cells from hyperosmolar stress, which can otherwise induce inflammatory responses.

Mechanism of Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Anti-inflammatory drugs are designed to disrupt the inflammatory cascade that underlies many cases of DES. Topical corticosteroids exert their effects by penetrating ocular tissues and binding to glucocorticoid receptors, ultimately inhibiting the transcription of various pro-inflammatory genes. This inhibition leads to reduced production of cytokines (for example, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) and enzymes such as MMPs that degrade extracellular matrix components—steps that are essential in the pathogenesis of DES.

Corticosteroids, when used in a short-term ‘pulse’ regimen, can quickly ameliorate signs of ocular surface inflammation, such as epithelial damage and hyperemia, thereby providing rapid symptomatic relief. However, given their potential side effects, such as elevation of intraocular pressure and cataract formation with long-term use, they are not considered for chronic management.

Non-steroidal treatments, such as tetracycline derivatives, work somewhat differently. Doxycycline, for example, has been demonstrated to reduce MMP-9 activity and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines. Beyond their anti-inflammatory actions, these agents are effective in managing associated conditions such as MGD by normalizing lipid secretion from the meibomian glands, thus addressing both the evaporative and inflammatory components of dry eye.

Mechanism of Immunomodulatory Agents

Immunomodulatory agents offer a more targeted approach by specifically modulating the immune response on the ocular surface. Cyclosporine A (CsA) is a prime example; its mechanism involves binding to cyclophilin in T cells, which prevents the activation of calcineurin and subsequent translocation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) into the nucleus. This cascade effectively blocks the transcription of interleukins, most notably IL-2, thereby reducing T-cell proliferation and inflammatory cytokine release.

Other immunomodulatory agents, such as lifitegrast, act by inhibiting leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) and its interaction with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on ocular surface cells. This blockade prevents the adhesion and migration of T cells to the ocular surface, reducing local inflammation and contributing to improved tear film quality. Emerging agents continue to refine this targeted approach, with several novel compounds now in late-phase clinical trials aiming to further reduce ocular surface inflammation with improved tolerability and rapid onset of action.

Clinical Efficacy and Considerations

The clinical success of any therapeutic strategy in dry eye syndrome is determined not only by its mechanism of action but also by its comparative effectiveness, safety profile, and suitability for individual patients. Clinicians must balance the benefits provided by each drug class against potential risks and consider the patient’s specific disease etiology, severity, and lifestyle issues alike.

Comparative Effectiveness

Artificial tears and lubricating agents provide immediate symptomatic relief by supplementing the tear film and are generally well tolerated. Their ease of access, over-the-counter availability, and wide range of formulations make them indispensable as first-line therapy. However, while they effectively alleviate discomfort in mild to moderate cases, they do not address the underlying inflammatory process found in more severe cases of DES.

Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as corticosteroids, offer rapid reduction in ocular surface inflammation, leading to improvements in clinical signs such as tear film break-up time (TBUT) and corneal staining scores. Nevertheless, these effects are often transient, and long-term use is limited by safety concerns. Studies have demonstrated that combining corticosteroids with other agents (e.g., lubricants) may enhance short-term benefits while paving the way for adjunctive therapy with immunomodulatory agents.

Immunomodulatory agents, particularly CsA and newer agents like lifitegrast, address the chronic inflammation that characterizes DES. Clinical studies have reported significant improvements in both objective clinical parameters and patient-reported symptoms with the use of these agents in refractory cases. Comparatively, the onset of action for these agents may be delayed relative to steroids but is more appropriate for long-term management without many of the associated adverse effects.

Side Effects and Safety Profiles

The choice of therapeutic agents is hindered by the potential for side effects, and it is crucial to carefully monitor safety profiles across drug classes. Lubricating agents are generally very safe; however, multi-dose formulations may contain preservatives that can cause ocular surface irritation if used frequently, particularly in patients with moderate to severe DES. Therefore, preservative-free or single-dose formulations are often preferred in chronic use.

Topical corticosteroids, although highly effective, carry an inherent risk of side effects with prolonged use. These include ocular hypertension, cataract formation, and potential predisposition to ocular infections. For this reason, corticosteroids are usually reserved for short-term “pulse” therapy and not as a long-term maintenance solution.

Immunomodulatory agents such as CsA have a well-established safety profile when used as directed, but they may cause a transient burning sensation upon instillation, which may affect patient compliance. Newer immunomodulators have strived to reduce such local irritation, and ongoing studies continue to refine their formulations toward better tolerability and ease of administration.

Patient-specific Considerations

In clinical practice, the selection of a treatment regimen for DES must consider patient-specific factors. For instance, a patient with a primary tear deficiency driven by lacrimal gland dysfunction—as seen in Sjögren’s syndrome—may benefit more from therapies that incorporate immunomodulatory agents in addition to lubricating drops. In contrast, patients with predominantly evaporative dry eye related to meibomian gland dysfunction might require additional treatments that address the lipid layer deficiency, such as lipid-containing artificial tears and even warm compress treatments.

Age is another important consideration; for example, older patients who may have difficulty administering eye drops may require formulations that are easy to dispense and cause minimal local irritation. Patients’ tolerance of multi-dose preservatives and the potential for preservative-induced toxicity should also be taken into account, leading clinicians to opt for preservative-free formulations when indicated. Similarly, individuals already burdened with systemic medications or coexisting ocular conditions may demand treatments that have minimal systemic absorption and an optimal safety profile over extended periods. In these cases, the judicious use of immunomodulatory agents becomes particularly advantageous because of their targeted mechanism and slower systemic absorption.

Summary and Conclusion

From a general perspective, dry eye syndrome represents a complex and multifactorial disorder that significantly impacts patient quality of life. Its pathogenesis involves a combination of tear film deficiency, rapid evaporation, and a self-perpetuating inflammatory process that damages the ocular surface. The treatment of DES is therefore inherently multifaceted, with different drug classes targeting distinct mechanisms in order to restore ocular surface homeostasis and alleviate symptoms.

Specifically, lubricating and moisturizing agents offer physical supplementation to the tear film by providing a viscous, protective layer which improves ocular surface hydration and minimizes friction, while also acting as a vehicle to dilute inflammatory mediators. Anti-inflammatory drugs, particularly corticosteroids and tetracycline derivatives, work by inhibiting the transcription and release of key cytokines and enzymes implicated in the chronic inflammation seen in DES. These agents help break the vicious inflammatory cycle but are often limited by their side effect profiles when used long-term. Immunomodulatory agents, such as cyclosporine A and lifitegrast, represent a more targeted approach. They specifically inhibit T-cell mediated inflammatory responses by blocking immune signaling pathways, leading to a sustained reduction in ocular surface inflammation and improved tear film function.

On a more specific level, the mechanism of action of lubricating agents revolves around their ability to mimic the natural composition of tears through the use of polymers and lipid components. These agents stabilize the tear film, improve retention time on the ocular surface, and also provide some degree of epithelial protection and healing. Anti-inflammatory medications reduce the synthesis of cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) and matrix metalloproteinases that disrupt the ocular surface and tear film, leading to a rapid improvement in clinical signs, albeit with potential side effects such as increased intraocular pressure and cataractogenesis if used indefinitely. Immunomodulatory agents, on the other hand, offer a more physiological correction of the chronic immune dysregulation present in severe dry eye by inhibiting T-cell activation and migration. This dampens the underlying inflammatory process, thereby allowing for long-term stabilization of the tear film and improved ocular surface integrity.

Finally, from a general perspective, the clinical efficacy of these treatments is determined by multiple factors. Comparative effectiveness shows that while lubricating agents are excellent for immediate relief, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory drugs are more effective for long-term management of moderate to severe conditions. Safety considerations are paramount, with the choice of therapy often dictated by the potential for adverse reactions and the patient’s underlying risk profile. Patient-specific factors, such as age, disease severity, and concurrent systemic medications, further refine the treatment plan, ensuring that the chosen therapy not only addresses the ocular pathology but is also tailored to the lifestyle and physiological needs of the individual patient.

In conclusion, the treatment of dry eye syndrome requires a comprehensive and personalized approach. The broad range of drug classes—from lubricating and moisturizing agents that provide immediate symptomatic relief to the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents that address the underlying pathogenic mechanisms—offers clinicians a versatile toolkit to manage this multifactorial disease effectively. An in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of action and the clinical considerations of each therapeutic option enables ophthalmologists to formulate treatment strategies that are both safe and effective, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes and quality of life. This integrated, hierarchical approach—from general symptomatic management to targeted immunomodulation—not only breaks the inflammatory vicious cycle but also paves the way for long-term restoration of ocular surface homeostasis, making it possible to tailor treatments to the diverse needs of patients suffering from dry eye syndromes.

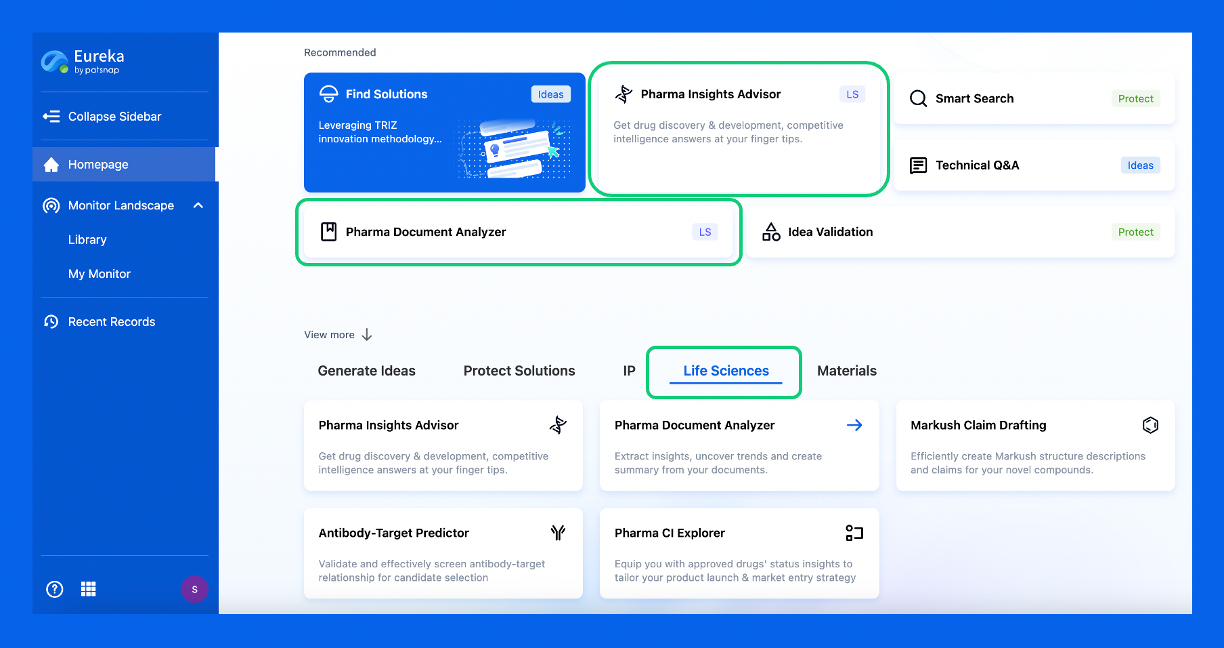

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.