Request Demo

How do different drug classes work in treating Endometriosis?

17 March 2025

Overview of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen‐dependent gynecological disease that is broadly characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity. This aberrant tissue can implant on various structures in the pelvis and even beyond, causing inflammation, scarring, and adhesion formation that underlie many of its clinical manifestations.

Definition and Symptoms

Endometriosis is defined by the ectopic presence and growth of endometrial mucosa and stroma outside of the uterus, most commonly on the ovaries, peritoneum, bowel surfaces, and other pelvic organs. Patients can experience a variety of symptoms; these range from cyclic pelvic pain (dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pain) to deep dyspareunia (painful intercourse), dyschezia (painful defecation), and even urinary symptoms in cases of bladder involvement. In addition, many women suffer from heavy menstrual bleeding and chronic fatigue. The clinical spectrum is broad, as some women remain asymptomatic while others report debilitating pain that severely affects their daily activities, work productivity, social relationships, and overall quality of life. Furthermore, the inflammation associated with these lesions contributes not only to local pain but may also influence fertility, as up to 30–50% of women with endometriosis struggle with infertility.

Current Treatment Landscape

The management of endometriosis is challenging because the disease is both chronic and heterogeneous in its presentations, with no definitive cure available. Traditionally, treatment strategies have involved either surgical intervention or medical management to alleviate pain symptoms, reduce lesion size, and improve fertility outcomes when desired by the patient. In clinical practice, the selection of a treatment modality is typically based on the severity of symptoms, the extent of the disease, the patient’s reproductive plans, and the balance between efficacy and side effects. Hormonal therapies remain the first-line medical option as they target the estrogen-dependent nature of the disease, while non-hormonal and emerging agents are gaining attention to address cases where existing treatments are either contraindicated or poorly tolerated.

Drug Classes Used in Endometriosis Treatment

Effective pharmacotherapy for endometriosis is built on two major drug classes: hormonal therapies and non-hormonal therapies. Each of these classes employs different mechanisms to achieve symptom relief and disease control, with their selection further tailored by patient-specific goals, especially regarding fertility preservation and long-term safety.

Hormonal Therapies

Hormonal therapies are currently the mainstay of medical treatment for endometriosis given the disease’s dependence on estrogen. The following drug classes are commonly used under hormonal management:

• Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs): These preparations typically contain both estrogen and progestin and work by suppressing ovulation, stabilizing the endometrium, and reducing menstrual flow which, in turn, decreases retrograde menstruation and local inflammatory mediators.

• Progestins: Administered either orally or as intrauterine devices, progestins act by inducing a decidualization and consequent atrophy of ectopic endometrial tissue. They exert direct effects on the endometrium by depressing estrogen receptor expression and reducing inflammatory cytokine production.

• Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Agonists and Antagonists: GnRH agonists downregulate the pituitary–gonadal axis by first causing a flare-up and then suppressing the secretion of gonadotropins, resulting in a hypoestrogenic state which reduces endometriotic lesion proliferation. In contrast, GnRH antagonists (e.g., elagolix) provide more rapid and adjustable estrogen suppression with a shorter half-life, enabling a dose-dependent balance between efficacy and side effects.

• Aromatase Inhibitors: These agents block the aromatase enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis, thereby reducing both ovarian and peripheral estrogen production, including local estrogen production within endometriotic lesions. Although effective, their use is often limited due to systemic hypoestrogenism.

• Selective Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Modulators (SERMs and SPRMs): SERMs act as estrogen receptor agonists or antagonists, depending on the target tissue, while SPRMs modulate progesterone receptor activity. They are designed to offer a more targeted hormonal effect with potentially fewer systemic side effects, although their clinical profile in endometriosis remains under investigation.

Non-Hormonal Therapies

While hormonal treatments tackle the estrogen receptor pathways, non-hormonal therapies aim to address other aspects of the disease’s multifactorial pathophysiology. Key non-hormonal options include:

• Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs are widely utilized to relieve endometriosis-associated pain primarily through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2), thereby reducing the synthesis of prostaglandins that contribute to inflammation and pain.

• Immunomodulators and Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Given the significant inflammatory component of endometriosis, agents targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α inhibitors) and other markers of inflammation are under investigation. These compounds aim to modulate the immune response that can perpetuate local inflammation and lesion growth.

• Anti-Angiogenic Agents: Endometriotic lesions are highly dependent on neovascularization for survival. Drugs that inhibit angiogenesis, such as selective inhibitors targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathways, aim to starve the lesions of their blood supply, thereby reducing lesion size and associated symptoms.

• Statins and Other Metabolic Modulators: Emerging evidence suggests that statins may exert anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects on endometriotic tissue, potentially through modulation of small GTPases and cytokine production. Furthermore, drugs like metformin, traditionally used in diabetes management, are being explored for their anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative benefits in endometriosis.

• Cannabinoids: Due to their multifaceted anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and neuromodulatory effects, cannabinoids are emerging as potential non-hormonal agents that may help manage chronic pain associated with endometriosis while preserving fertility.

Mechanisms of Action

Hormonal Therapies

Hormonal treatments for endometriosis principally work by manipulating the endocrine milieu that supports the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue. Their mechanisms of action include:

• Ovarian Suppression and Hypoestrogenism: Nearly all hormonal therapies, including COCs, progestins, GnRH agonists/antagonists, and aromatase inhibitors, aim to lower systemic and local estrogen levels. By suppressing ovulation and inducing a hypoestrogenic state, these drugs reduce the estrogen-driven proliferation of endometriotic lesions. For example, GnRH agonists initially stimulate but then desensitize the pituitary receptors, leading to reduced circulating gonadotropins and subsequent estrogen depletion.

• Endometrial Decidualization and Atrophy: Progestins promote decidualization of the endometrial tissue and eventually cause atrophy of both eutopic and ectopic endometrium. This mechanism not only reduces lesion size but also blunts the inflammatory response by decreasing the expression of estrogen receptors and inflammatory mediators.

• Inhibition of Local Estrogen Biosynthesis: Aromatase inhibitors block the conversion of androgens to estrogens by inhibiting the aromatase enzyme, which is often overexpressed in endometriotic lesions. This reduction in local estrogen synthesis can lead to decreased proliferation of ectopic endometrial cells.

• Selective Modulation of Estrogen/Progesterone Receptors: SERMs and SPRMs allow for tissue-selective action on hormone receptors. These agents work by providing agonistic or antagonistic activity at estrogen or progesterone receptors in endometriotic tissue, thereby potentially offering beneficial effects without the systemic side effects associated with non-selective hormonal suppression.

• Feedback and Downregulation Mechanisms: In addition to direct suppression of estrogen production, many hormonal agents invoke negative feedback loops at the hypothalamic-pituitary axis to further reduce gonadotropin release. This multi-level approach reinforces the hypoestrogenic state that is detrimental to endometriotic lesion survival.

Non-Hormonal Therapies

Non-hormonal therapies operate on distinct molecular and cellular processes that are integral to the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Their mechanisms include:

• Anti-Inflammatory Action: NSAIDs function primarily by inhibiting cyclooxygenase enzymes, thus reducing the production of prostaglandins that are key mediators of pain and inflammation. In addition, other anti-inflammatory agents and immunomodulators target specific cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, which have been implicated in sustaining chronic inflammation within endometriotic lesions.

• Anti-Angiogenesis: Endometriotic lesions require a robust blood supply to survive and grow. Anti-angiogenic drugs target signaling pathways (such as the VEGF pathway) that promote new blood vessel formation, thereby limiting the vascular support required for lesion proliferation.

• Immunomodulation: Since endometriosis is associated with alterations in immune surveillance and local immune cell populations (e.g., natural killer cells and macrophages), agents that modulate these immune responses can potentially reduce lesion survival and inflammation.

• Metabolic Reprogramming: Some non-hormonal agents, such as metformin, modulate metabolic pathways and have been shown to exert antiproliferative effects on endometriotic cells. Metformin’s mechanism appears to involve inhibition of aromatase activity as well as a reduction in inflammatory cytokine production, thereby simultaneously targeting both the proliferative and inflammatory components of endometriosis.

• Neuromodulation: Emerging evidence suggests that cannabinoids may alleviate endometriosis-associated pain by acting on the endocannabinoid system, which modulates nociception, immune response, and inflammation. Their multifaceted mechanism offers a promising alternative approach with potentially fewer reproductive side effects.

Comparative Effectiveness

Clinical Studies and Data

Clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of hormonal versus non-hormonal treatments with a focus on pain reduction, quality of life improvements, and recurrence rates after intervention. For instance, GnRH antagonists such as elagolix have demonstrated dose-dependent improvements in endometriosis-associated pain with a rapid onset of effect and reversible hypoestrogenic profiles, as evidenced in several phase III trials. Clinical data have shown that while COCs and progestins are effective in a majority of patients, approximately one-third of women do not achieve adequate symptom relief, necessitating alternative or adjunct therapies. Comparisons between GnRH agonists and antagonists have revealed that antagonists may offer similar efficacy with a more manageable side effect profile and better tolerability, making them especially appealing for long-term management. Non-hormonal agents like NSAIDs offer immediate relief from inflammatory pain, though their efficacy is generally inferior to that of hormonal therapies in addressing the underlying pathology or preventing lesion progression. Meanwhile, emerging therapies such as aromatase inhibitors and selective receptor modulators have demonstrated promising results in small-scale studies but still lack the extensive clinical validation of more established hormonal treatments. In addition, randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews comparing these agents have indicated that while hormonal therapies reliably reduce circulating estrogen and produce symptomatic relief, they often lead to adverse effects—an issue that non-hormonal approaches may help mitigate in certain patient populations.

Side Effects and Patient Outcomes

The choice between hormonal and non-hormonal treatments is strongly influenced by the side effect profiles and overall patient outcomes observed in clinical practice.

• Hormonal Therapies: The suppression of ovarian function, while effective, can lead to a constellation of hypoestrogenic side effects. GnRH agonists, for example, are associated with menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, decreased bone mineral density, and mood changes. Combined oral contraceptives and progestins may cause weight gain, bloating, breakthrough bleeding, and in some cases, mood disturbances or intolerance to the contraceptive effect, which can complicate treatment in women desiring pregnancy. Moreover, the long-term use of these agents is often limited by their side effect burden, which in turn affects adherence and patient satisfaction.

• Non-Hormonal Therapies: NSAIDs are generally well tolerated when used intermittently; however, their chronic use can be limited by gastrointestinal toxicity, cardiovascular risks, and renal issues in susceptible populations. Immunomodulators and anti-angiogenic agents, while promising, remain under investigation with concerns about off-target effects and potential immunosuppression. Agents such as metformin have demonstrated a favorable safety profile in populations such as women with polycystic ovary syndrome and are now being repurposed, with early studies suggesting that metformin may have both anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative benefits in endometriosis without significant endocrine disruption. Additionally, novel treatments like cannabinoids may offer analgesia and anti-inflammatory effects with a lower risk of hormonal side effects, though their legal status, standardization, and long-term outcomes continue to be areas of active research. Overall, while hormonal therapies remain the most effective in terms of lesion suppression and long-term symptom control, non-hormonal therapies provide an important complementary approach, particularly in patients who prioritize fertility or who experience unacceptable side effects from hormonal agents.

Future Directions in Treatment

Emerging Therapies

Recent advancements in understanding the pathophysiology of endometriosis have spurred the development of several novel therapeutic approaches aimed at improving efficacy and reducing adverse effects. Among the most promising emerging treatments are:

• Next-Generation GnRH Antagonists: New oral GnRH antagonists are being developed with more precise dose control to achieve a balance between reducing endometriosis-associated pain while limiting hypoestrogenic side effects. Their rapid onset and reversibility are making them attractive alternatives to conventional GnRH agonists.

• Selective Receptor Modulators: Continued research into SERMs and SPRMs is yielding compounds that may offer tissue-selective modulation of estrogen and progesterone receptors, potentially providing effective lesion control with fewer systemic effects.

• Anti-Angiogenic and Immunomodulatory Agents: As studies increasingly unravel the importance of angiogenesis and immune dysregulation in lesion survival, drugs targeting VEGF signaling and inflammatory cytokines are emerging as novel pharmaceutical strategies. Early-phase trials of anti-angiogenic compounds show that targeting neovascularization can limit lesion growth and pain. Similarly, immunomodulators targeting pathways such as TNF-α or NF-κB may offer dual benefits in reducing chronic inflammation and controlling lesion progression.

• Metabolic Modulators: With drugs like metformin showing promise in reducing aromatase activity locally and exerting anti-inflammatory effects, further investigations are underway to characterize their role either as standalone therapies or in combination with hormonal treatments.

• Cannabinoids: The analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of cannabinoids are being actively explored, particularly given their potential to manage chronic pain without compromising fertility. Their ability to target multiple pain pathways gives them an edge in addressing the often multifactorial etiology of endometriosis-associated pain.

Research and Development Trends

Looking ahead, research in endometriosis treatment is moving toward a more personalized, precision medicine approach by integrating clinical, genomic, and molecular data. Key trends include:

• Drug Repurposing: Leveraging the safety profiles of existing medications such as metformin and statins, researchers are repurposing these agents for endometriosis treatment. Early data suggest that such approaches could complement or even replace some of the current therapies, particularly in patients with refractory symptoms.

• Biomarker-Driven Therapy: The identification of molecular markers associated with endometriosis progression and treatment response is paving the way for more tailored interventions. Advances in high-throughput sequencing and integrated omics data are enabling clinicians to stratify patients based on disease phenotype, which may direct them toward specific hormonal or non-hormonal treatments.

• Digital Health and Electronic Health Records: The integration of clinical data through electronic health records (EHRs) and the application of artificial intelligence (AI) are anticipated to enhance our understanding of disease heterogeneity. These developments will likely lead to improved patient stratification, risk prediction models, and individualized therapeutic strategies for managing endometriosis.

• Combination Therapies: Given the complex, multifactorial nature of endometriosis, it is becoming increasingly clear that a single-agent approach may not be sufficient. Future treatment strategies are likely to include combination therapies that target multiple pathogenic pathways simultaneously, such as combining hormonal suppression with anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory agents, to achieve a synergistic effect.

• Long-Term Safety and Patient-Centered Outcomes: Ongoing clinical trials are placing greater emphasis on not only short-term efficacy but also long-term safety, quality of life, and fertility outcomes. This trend is influencing drug development priorities and could lead to a new generation of therapies that minimize adverse effects while maximizing patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of endometriosis encompasses a broad spectrum of drug classes that work by targeting different aspects of the disease’s complex pathophysiology. Hormonal therapies act primarily by suppressing ovarian function and lowering estrogen levels, thereby reducing the estrogen-dependent growth and inflammation of ectopic endometrial tissue. These agents – including combined oral contraceptives, progestins, GnRH agonists/antagonists, aromatase inhibitors, and selective receptor modulators – are effective in alleviating pain and reducing lesion size but are often limited by their side effect profiles and contraceptive effects, which can be particularly problematic for women who wish to conceive.

On the other hand, non-hormonal therapies target different mechanisms such as inflammation, angiogenesis, and immune dysregulation. NSAIDs provide symptomatic relief by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, while emerging agents such as immunomodulators, anti-angiogenic drugs, metabolic modulators like metformin, and cannabinoids offer novel avenues for reducing lesion survival and chronic pain with potentially fewer reproductive side effects. Comparative studies reveal that although hormonal treatments remain the cornerstone of therapy given their robust efficacy, non-hormonal options play a crucial role in managing those patients who are either resistant to or cannot tolerate hormonal treatments.

Looking to the future, research in endometriosis is increasingly focused on emerging therapies that promise improved efficacy and reduced side effects. Advances in precision medicine, driven by the integration of omics data and electronic health records, are enabling a more personalized approach to therapy. Novel agents such as next-generation GnRH antagonists, selective receptor modulators, anti-angiogenic compounds, and repurposed drugs like metformin are at various stages of clinical development and hold the potential for more effective and individualized treatment strategies. Along with these pharmacological innovations, the emphasis on understanding and addressing patient quality of life and long-term treatment outcomes is expected to guide future research directions.

In conclusion, different drug classes for endometriosis work through complementary mechanisms—hormonal therapies primarily target estrogen-mediated proliferation and inflammation, whereas non-hormonal therapies focus on reducing inflammation, angiogenesis, and lesion vascularization, among other pathways. The clinical decision-making process is influenced by both the effectiveness of these therapies and their side effect profiles, with future treatment paradigms likely to involve personalized, combination therapy approaches that optimize patient outcomes. As multidisciplinary research efforts continue to expand our understanding of endometriosis pathogenesis and treatment response, the next generation of therapies promises to balance improved efficacy with enhanced safety and tolerability, ultimately advancing the quality of life for affected women.

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen‐dependent gynecological disease that is broadly characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity. This aberrant tissue can implant on various structures in the pelvis and even beyond, causing inflammation, scarring, and adhesion formation that underlie many of its clinical manifestations.

Definition and Symptoms

Endometriosis is defined by the ectopic presence and growth of endometrial mucosa and stroma outside of the uterus, most commonly on the ovaries, peritoneum, bowel surfaces, and other pelvic organs. Patients can experience a variety of symptoms; these range from cyclic pelvic pain (dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pain) to deep dyspareunia (painful intercourse), dyschezia (painful defecation), and even urinary symptoms in cases of bladder involvement. In addition, many women suffer from heavy menstrual bleeding and chronic fatigue. The clinical spectrum is broad, as some women remain asymptomatic while others report debilitating pain that severely affects their daily activities, work productivity, social relationships, and overall quality of life. Furthermore, the inflammation associated with these lesions contributes not only to local pain but may also influence fertility, as up to 30–50% of women with endometriosis struggle with infertility.

Current Treatment Landscape

The management of endometriosis is challenging because the disease is both chronic and heterogeneous in its presentations, with no definitive cure available. Traditionally, treatment strategies have involved either surgical intervention or medical management to alleviate pain symptoms, reduce lesion size, and improve fertility outcomes when desired by the patient. In clinical practice, the selection of a treatment modality is typically based on the severity of symptoms, the extent of the disease, the patient’s reproductive plans, and the balance between efficacy and side effects. Hormonal therapies remain the first-line medical option as they target the estrogen-dependent nature of the disease, while non-hormonal and emerging agents are gaining attention to address cases where existing treatments are either contraindicated or poorly tolerated.

Drug Classes Used in Endometriosis Treatment

Effective pharmacotherapy for endometriosis is built on two major drug classes: hormonal therapies and non-hormonal therapies. Each of these classes employs different mechanisms to achieve symptom relief and disease control, with their selection further tailored by patient-specific goals, especially regarding fertility preservation and long-term safety.

Hormonal Therapies

Hormonal therapies are currently the mainstay of medical treatment for endometriosis given the disease’s dependence on estrogen. The following drug classes are commonly used under hormonal management:

• Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs): These preparations typically contain both estrogen and progestin and work by suppressing ovulation, stabilizing the endometrium, and reducing menstrual flow which, in turn, decreases retrograde menstruation and local inflammatory mediators.

• Progestins: Administered either orally or as intrauterine devices, progestins act by inducing a decidualization and consequent atrophy of ectopic endometrial tissue. They exert direct effects on the endometrium by depressing estrogen receptor expression and reducing inflammatory cytokine production.

• Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Agonists and Antagonists: GnRH agonists downregulate the pituitary–gonadal axis by first causing a flare-up and then suppressing the secretion of gonadotropins, resulting in a hypoestrogenic state which reduces endometriotic lesion proliferation. In contrast, GnRH antagonists (e.g., elagolix) provide more rapid and adjustable estrogen suppression with a shorter half-life, enabling a dose-dependent balance between efficacy and side effects.

• Aromatase Inhibitors: These agents block the aromatase enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis, thereby reducing both ovarian and peripheral estrogen production, including local estrogen production within endometriotic lesions. Although effective, their use is often limited due to systemic hypoestrogenism.

• Selective Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Modulators (SERMs and SPRMs): SERMs act as estrogen receptor agonists or antagonists, depending on the target tissue, while SPRMs modulate progesterone receptor activity. They are designed to offer a more targeted hormonal effect with potentially fewer systemic side effects, although their clinical profile in endometriosis remains under investigation.

Non-Hormonal Therapies

While hormonal treatments tackle the estrogen receptor pathways, non-hormonal therapies aim to address other aspects of the disease’s multifactorial pathophysiology. Key non-hormonal options include:

• Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs are widely utilized to relieve endometriosis-associated pain primarily through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2), thereby reducing the synthesis of prostaglandins that contribute to inflammation and pain.

• Immunomodulators and Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Given the significant inflammatory component of endometriosis, agents targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α inhibitors) and other markers of inflammation are under investigation. These compounds aim to modulate the immune response that can perpetuate local inflammation and lesion growth.

• Anti-Angiogenic Agents: Endometriotic lesions are highly dependent on neovascularization for survival. Drugs that inhibit angiogenesis, such as selective inhibitors targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathways, aim to starve the lesions of their blood supply, thereby reducing lesion size and associated symptoms.

• Statins and Other Metabolic Modulators: Emerging evidence suggests that statins may exert anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects on endometriotic tissue, potentially through modulation of small GTPases and cytokine production. Furthermore, drugs like metformin, traditionally used in diabetes management, are being explored for their anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative benefits in endometriosis.

• Cannabinoids: Due to their multifaceted anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and neuromodulatory effects, cannabinoids are emerging as potential non-hormonal agents that may help manage chronic pain associated with endometriosis while preserving fertility.

Mechanisms of Action

Hormonal Therapies

Hormonal treatments for endometriosis principally work by manipulating the endocrine milieu that supports the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue. Their mechanisms of action include:

• Ovarian Suppression and Hypoestrogenism: Nearly all hormonal therapies, including COCs, progestins, GnRH agonists/antagonists, and aromatase inhibitors, aim to lower systemic and local estrogen levels. By suppressing ovulation and inducing a hypoestrogenic state, these drugs reduce the estrogen-driven proliferation of endometriotic lesions. For example, GnRH agonists initially stimulate but then desensitize the pituitary receptors, leading to reduced circulating gonadotropins and subsequent estrogen depletion.

• Endometrial Decidualization and Atrophy: Progestins promote decidualization of the endometrial tissue and eventually cause atrophy of both eutopic and ectopic endometrium. This mechanism not only reduces lesion size but also blunts the inflammatory response by decreasing the expression of estrogen receptors and inflammatory mediators.

• Inhibition of Local Estrogen Biosynthesis: Aromatase inhibitors block the conversion of androgens to estrogens by inhibiting the aromatase enzyme, which is often overexpressed in endometriotic lesions. This reduction in local estrogen synthesis can lead to decreased proliferation of ectopic endometrial cells.

• Selective Modulation of Estrogen/Progesterone Receptors: SERMs and SPRMs allow for tissue-selective action on hormone receptors. These agents work by providing agonistic or antagonistic activity at estrogen or progesterone receptors in endometriotic tissue, thereby potentially offering beneficial effects without the systemic side effects associated with non-selective hormonal suppression.

• Feedback and Downregulation Mechanisms: In addition to direct suppression of estrogen production, many hormonal agents invoke negative feedback loops at the hypothalamic-pituitary axis to further reduce gonadotropin release. This multi-level approach reinforces the hypoestrogenic state that is detrimental to endometriotic lesion survival.

Non-Hormonal Therapies

Non-hormonal therapies operate on distinct molecular and cellular processes that are integral to the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Their mechanisms include:

• Anti-Inflammatory Action: NSAIDs function primarily by inhibiting cyclooxygenase enzymes, thus reducing the production of prostaglandins that are key mediators of pain and inflammation. In addition, other anti-inflammatory agents and immunomodulators target specific cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, which have been implicated in sustaining chronic inflammation within endometriotic lesions.

• Anti-Angiogenesis: Endometriotic lesions require a robust blood supply to survive and grow. Anti-angiogenic drugs target signaling pathways (such as the VEGF pathway) that promote new blood vessel formation, thereby limiting the vascular support required for lesion proliferation.

• Immunomodulation: Since endometriosis is associated with alterations in immune surveillance and local immune cell populations (e.g., natural killer cells and macrophages), agents that modulate these immune responses can potentially reduce lesion survival and inflammation.

• Metabolic Reprogramming: Some non-hormonal agents, such as metformin, modulate metabolic pathways and have been shown to exert antiproliferative effects on endometriotic cells. Metformin’s mechanism appears to involve inhibition of aromatase activity as well as a reduction in inflammatory cytokine production, thereby simultaneously targeting both the proliferative and inflammatory components of endometriosis.

• Neuromodulation: Emerging evidence suggests that cannabinoids may alleviate endometriosis-associated pain by acting on the endocannabinoid system, which modulates nociception, immune response, and inflammation. Their multifaceted mechanism offers a promising alternative approach with potentially fewer reproductive side effects.

Comparative Effectiveness

Clinical Studies and Data

Clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of hormonal versus non-hormonal treatments with a focus on pain reduction, quality of life improvements, and recurrence rates after intervention. For instance, GnRH antagonists such as elagolix have demonstrated dose-dependent improvements in endometriosis-associated pain with a rapid onset of effect and reversible hypoestrogenic profiles, as evidenced in several phase III trials. Clinical data have shown that while COCs and progestins are effective in a majority of patients, approximately one-third of women do not achieve adequate symptom relief, necessitating alternative or adjunct therapies. Comparisons between GnRH agonists and antagonists have revealed that antagonists may offer similar efficacy with a more manageable side effect profile and better tolerability, making them especially appealing for long-term management. Non-hormonal agents like NSAIDs offer immediate relief from inflammatory pain, though their efficacy is generally inferior to that of hormonal therapies in addressing the underlying pathology or preventing lesion progression. Meanwhile, emerging therapies such as aromatase inhibitors and selective receptor modulators have demonstrated promising results in small-scale studies but still lack the extensive clinical validation of more established hormonal treatments. In addition, randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews comparing these agents have indicated that while hormonal therapies reliably reduce circulating estrogen and produce symptomatic relief, they often lead to adverse effects—an issue that non-hormonal approaches may help mitigate in certain patient populations.

Side Effects and Patient Outcomes

The choice between hormonal and non-hormonal treatments is strongly influenced by the side effect profiles and overall patient outcomes observed in clinical practice.

• Hormonal Therapies: The suppression of ovarian function, while effective, can lead to a constellation of hypoestrogenic side effects. GnRH agonists, for example, are associated with menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, decreased bone mineral density, and mood changes. Combined oral contraceptives and progestins may cause weight gain, bloating, breakthrough bleeding, and in some cases, mood disturbances or intolerance to the contraceptive effect, which can complicate treatment in women desiring pregnancy. Moreover, the long-term use of these agents is often limited by their side effect burden, which in turn affects adherence and patient satisfaction.

• Non-Hormonal Therapies: NSAIDs are generally well tolerated when used intermittently; however, their chronic use can be limited by gastrointestinal toxicity, cardiovascular risks, and renal issues in susceptible populations. Immunomodulators and anti-angiogenic agents, while promising, remain under investigation with concerns about off-target effects and potential immunosuppression. Agents such as metformin have demonstrated a favorable safety profile in populations such as women with polycystic ovary syndrome and are now being repurposed, with early studies suggesting that metformin may have both anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative benefits in endometriosis without significant endocrine disruption. Additionally, novel treatments like cannabinoids may offer analgesia and anti-inflammatory effects with a lower risk of hormonal side effects, though their legal status, standardization, and long-term outcomes continue to be areas of active research. Overall, while hormonal therapies remain the most effective in terms of lesion suppression and long-term symptom control, non-hormonal therapies provide an important complementary approach, particularly in patients who prioritize fertility or who experience unacceptable side effects from hormonal agents.

Future Directions in Treatment

Emerging Therapies

Recent advancements in understanding the pathophysiology of endometriosis have spurred the development of several novel therapeutic approaches aimed at improving efficacy and reducing adverse effects. Among the most promising emerging treatments are:

• Next-Generation GnRH Antagonists: New oral GnRH antagonists are being developed with more precise dose control to achieve a balance between reducing endometriosis-associated pain while limiting hypoestrogenic side effects. Their rapid onset and reversibility are making them attractive alternatives to conventional GnRH agonists.

• Selective Receptor Modulators: Continued research into SERMs and SPRMs is yielding compounds that may offer tissue-selective modulation of estrogen and progesterone receptors, potentially providing effective lesion control with fewer systemic effects.

• Anti-Angiogenic and Immunomodulatory Agents: As studies increasingly unravel the importance of angiogenesis and immune dysregulation in lesion survival, drugs targeting VEGF signaling and inflammatory cytokines are emerging as novel pharmaceutical strategies. Early-phase trials of anti-angiogenic compounds show that targeting neovascularization can limit lesion growth and pain. Similarly, immunomodulators targeting pathways such as TNF-α or NF-κB may offer dual benefits in reducing chronic inflammation and controlling lesion progression.

• Metabolic Modulators: With drugs like metformin showing promise in reducing aromatase activity locally and exerting anti-inflammatory effects, further investigations are underway to characterize their role either as standalone therapies or in combination with hormonal treatments.

• Cannabinoids: The analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of cannabinoids are being actively explored, particularly given their potential to manage chronic pain without compromising fertility. Their ability to target multiple pain pathways gives them an edge in addressing the often multifactorial etiology of endometriosis-associated pain.

Research and Development Trends

Looking ahead, research in endometriosis treatment is moving toward a more personalized, precision medicine approach by integrating clinical, genomic, and molecular data. Key trends include:

• Drug Repurposing: Leveraging the safety profiles of existing medications such as metformin and statins, researchers are repurposing these agents for endometriosis treatment. Early data suggest that such approaches could complement or even replace some of the current therapies, particularly in patients with refractory symptoms.

• Biomarker-Driven Therapy: The identification of molecular markers associated with endometriosis progression and treatment response is paving the way for more tailored interventions. Advances in high-throughput sequencing and integrated omics data are enabling clinicians to stratify patients based on disease phenotype, which may direct them toward specific hormonal or non-hormonal treatments.

• Digital Health and Electronic Health Records: The integration of clinical data through electronic health records (EHRs) and the application of artificial intelligence (AI) are anticipated to enhance our understanding of disease heterogeneity. These developments will likely lead to improved patient stratification, risk prediction models, and individualized therapeutic strategies for managing endometriosis.

• Combination Therapies: Given the complex, multifactorial nature of endometriosis, it is becoming increasingly clear that a single-agent approach may not be sufficient. Future treatment strategies are likely to include combination therapies that target multiple pathogenic pathways simultaneously, such as combining hormonal suppression with anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory agents, to achieve a synergistic effect.

• Long-Term Safety and Patient-Centered Outcomes: Ongoing clinical trials are placing greater emphasis on not only short-term efficacy but also long-term safety, quality of life, and fertility outcomes. This trend is influencing drug development priorities and could lead to a new generation of therapies that minimize adverse effects while maximizing patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of endometriosis encompasses a broad spectrum of drug classes that work by targeting different aspects of the disease’s complex pathophysiology. Hormonal therapies act primarily by suppressing ovarian function and lowering estrogen levels, thereby reducing the estrogen-dependent growth and inflammation of ectopic endometrial tissue. These agents – including combined oral contraceptives, progestins, GnRH agonists/antagonists, aromatase inhibitors, and selective receptor modulators – are effective in alleviating pain and reducing lesion size but are often limited by their side effect profiles and contraceptive effects, which can be particularly problematic for women who wish to conceive.

On the other hand, non-hormonal therapies target different mechanisms such as inflammation, angiogenesis, and immune dysregulation. NSAIDs provide symptomatic relief by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, while emerging agents such as immunomodulators, anti-angiogenic drugs, metabolic modulators like metformin, and cannabinoids offer novel avenues for reducing lesion survival and chronic pain with potentially fewer reproductive side effects. Comparative studies reveal that although hormonal treatments remain the cornerstone of therapy given their robust efficacy, non-hormonal options play a crucial role in managing those patients who are either resistant to or cannot tolerate hormonal treatments.

Looking to the future, research in endometriosis is increasingly focused on emerging therapies that promise improved efficacy and reduced side effects. Advances in precision medicine, driven by the integration of omics data and electronic health records, are enabling a more personalized approach to therapy. Novel agents such as next-generation GnRH antagonists, selective receptor modulators, anti-angiogenic compounds, and repurposed drugs like metformin are at various stages of clinical development and hold the potential for more effective and individualized treatment strategies. Along with these pharmacological innovations, the emphasis on understanding and addressing patient quality of life and long-term treatment outcomes is expected to guide future research directions.

In conclusion, different drug classes for endometriosis work through complementary mechanisms—hormonal therapies primarily target estrogen-mediated proliferation and inflammation, whereas non-hormonal therapies focus on reducing inflammation, angiogenesis, and lesion vascularization, among other pathways. The clinical decision-making process is influenced by both the effectiveness of these therapies and their side effect profiles, with future treatment paradigms likely to involve personalized, combination therapy approaches that optimize patient outcomes. As multidisciplinary research efforts continue to expand our understanding of endometriosis pathogenesis and treatment response, the next generation of therapies promises to balance improved efficacy with enhanced safety and tolerability, ultimately advancing the quality of life for affected women.

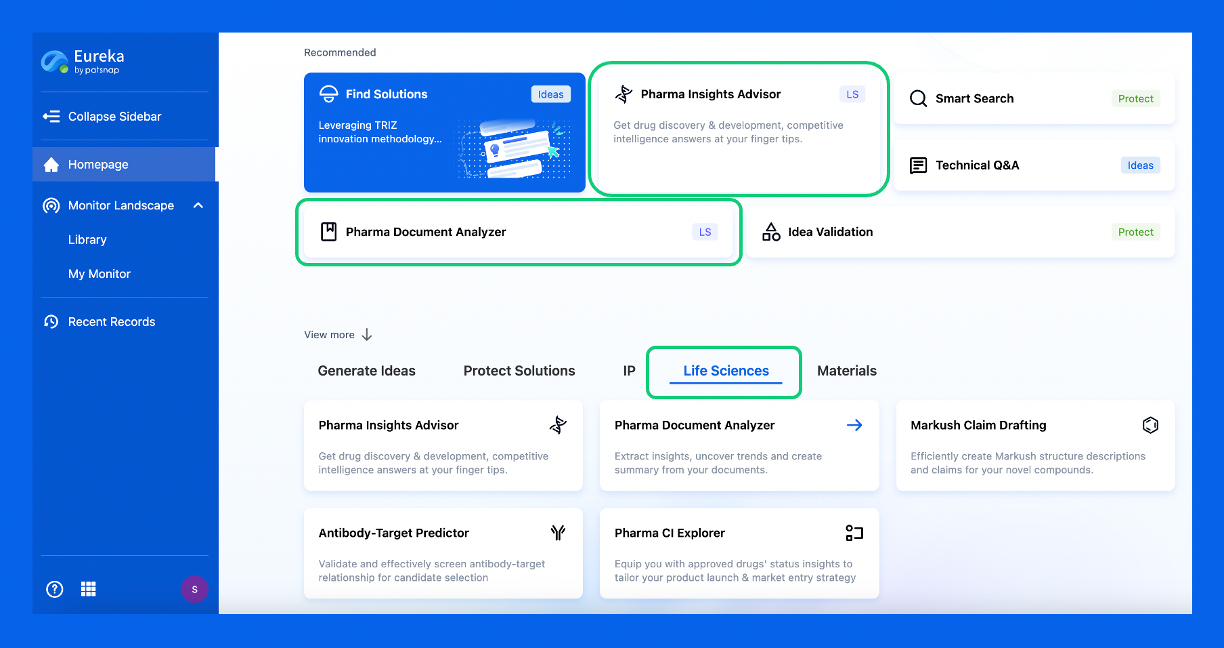

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.