Request Demo

How do different drug classes work in treating Knee Arthritis?

17 March 2025

Introduction to Knee Arthritis

Knee arthritis is a chronic, degenerative joint disease that affects the articular structures of the knee, including the cartilage, subchondral bone, ligaments, and synovial membrane. It is characterized by progressive joint degeneration, leading to pain, stiffness, and functional impairment. Over time, these changes may culminate in joint instability and significant disability, profoundly affecting quality of life.

Types and SymptomsKnee arthritisis encompasses several clinical entities. The most common is osteoarthritis, often termed degenerative joint disease, where the cumulative effect of mechanical stress on the joint and biological aging results in cartilage degradation and bone spur formation. In contrast, rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic autoimmune condition that causes inflammation primarily of the synovium, leading to joint destruction and extra-articular manifestations. Other variants include post-traumatic arthritis, which ensues after joint injury, and secondary arthritis resulting from metabolic or other systemic conditions. Clinically, patients present with joint pain which is typically worsened by activity and relieved by rest, morning stiffness that usually improves within 30 minutes, and a reduction in range of motion. Some patients may also experience joint swelling, crepitus, and occasional episodes of acute inflammation.

Prevalence and Impact

Knee arthritis is increasingly prevalent worldwide, particularly among the elderly and those with obesity, where the cumulative biomechanical stress and inflammatory milieu accelerate joint degeneration. Recent epidemiological data indicate that approximately 40% of individuals over 65 years suffer from symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, and osteoarthritis is a leading cause of disability and reduced mobility in older populations. The impact is not only clinical—with patients experiencing chronic pain and decreased function—but also socioeconomic, as it often results in a loss of work productivity, increased healthcare utilization, and the need for joint replacement surgeries when the disease progresses to its end stage.

Drug Classes for Knee Arthritis

Managing knee arthritis, particularly osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, typically involves a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Among the pharmacological treatments, three key drug classes are most commonly used: Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), Corticosteroids, and Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs). Each class works via a different mechanism of action, targets varied inflammatory pathways, and offers distinct benefits and pitfalls depending on the clinical scenario.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are widely prescribed to alleviate the pain and inflammation associated with knee arthritis. They are often the first-line therapy in many clinical guidelines, ensuring that patients obtain rapid, symptomatic relief. These drugs are available in oral, topical, and sometimes injectable formulations. The efficacy of NSAIDs has been established through numerous randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. They are particularly valued because of their dual action: reducing pain perception by inhibiting inflammatory mediators and diminishing the overall inflammatory process in the joint. However, while NSAIDs offer significant pain relief, their use is often limited by concerns regarding systemic adverse effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiovascular events, and renal impairment, especially with long-term use. Recent comparisons have also shown that while topical NSAIDs provide similar efficacy to oral agents, they tend to have a better safety profile in high-risk populations.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, particularly when administered via intra-articular injection, are used primarily for short-term relief of acute flare-ups in knee arthritis. These potent anti-inflammatory agents act more broadly on the inflammatory cascade compared to NSAIDs. They suppress the inflammatory response not only by inhibiting enzymes and pathways similar to those targeted by NSAIDs but also by modulating immune cell function and cytokine production on a genomic level. In clinical practice, intra-articular corticosteroid injections are often employed when oral agents fail to control acute exacerbations, providing rapid pain relief that may last for several weeks. Despite their potent local anti-inflammatory effects, systemic absorption can occur with repeated injections, and there is a possibility of long-term deleterious effects on the joint structures, such as cartilage thinning or damage with excessive use over time.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)

DMARDs represent a heterogeneous group of medications that are used not only to alleviate symptoms but also to impede the progressive joint destruction characteristic of inflammatory arthritis, most notably rheumatoid arthritis. DMARDs are subdivided into conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine, and biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), which include agents targeting tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins, and other specific immune pathways. In recent years, targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) have also emerged. These drugs provide a disease-modifying effect by inhibiting specific mediators of inflammation and immune response at the cellular and molecular levels, thereby reducing synovial inflammation, decelerating structural joint damage, and maintaining joint function over the long term. DMARD therapy is especially critical in rheumatoid arthritis, where controlling the immune-mediated inflammatory process can prevent irreversible joint destructions and systemic complications.

Mechanisms of Action

The way in which these drug classes work to alleviate symptoms and alter the disease course in knee arthritis is rooted in their distinct biochemical and cellular mechanisms. Understanding these mechanisms helps clinicians tailor therapy according to the severity of the disease, patient comorbidities, and the risk–benefit profile.

How NSAIDs Work

NSAIDs exert their therapeutic effects predominantly by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes—COX-1 and COX-2. These enzymes catalyze the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, which are key mediators of inflammation, pain, and fever.

1. Inhibition of Prostaglandin Synthesis:

By blocking COX activity, NSAIDs reduce the synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a mediator responsible for pain sensitization, vasodilation, and inflammatory responses. This biochemical inhibition leads to a decrease in both the pain sensation and the inflammatory process within the joint.

2. Selective Versus Nonselective Inhibition:

Traditional NSAIDs inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2. Inhibition of COX-1 is associated with adverse gastrointestinal and renal effects because COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues and serves physiological functions such as protecting the gastric mucosa, regulating renal blood flow, and aiding in platelet aggregation. Conversely, COX-2 selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) target the inducible form of the enzyme, which is upregulated during inflammation, thereby offering pain relief with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. However, even COX-2 inhibitors are not without risk, as they have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in some studies.

3. Topical NSAIDs:

The development of topical NSAIDs aims to localize the drug effect to the joint region while minimizing systemic exposure. This formulation delivers sufficient concentration to inhibit local COX activity and reduce pain and inflammation while avoiding many of the systemic adverse effects seen with oral NSAIDs.

Mechanism of Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids work through a different pathway compared to NSAIDs, providing a broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effect by modulating the transcription of numerous genes involved in the inflammatory response.

1. Transcriptional Regulation:

Corticosteroids penetrate the cell membrane and bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the cytoplasm. The steroid–receptor complex then translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) on the DNA. This binding results in upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes and downregulation of pro-inflammatory genes, including those encoding cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha) as well as enzymes such as COX-2.

2. Inhibition of Cytokine Production:

By reducing the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines along with the inhibition of leukocyte infiltration, corticosteroids effectively blunt the inflammatory cascade. This mechanism is particularly beneficial in dampening the acute inflammatory flare-ups seen in knee arthritis, allowing for rapid symptomatic improvement.

3. Depot Effect with Injections:

When administered intra-articularly, corticosteroids form a depot within the joint space, permitting a slow release of the active agent. This allows for sustained anti-inflammatory activity at the site of pathology for several weeks. However, long-term or repeated injections must be approached with caution as they might lead to joint structural changes such as cartilage thinning or degeneration over time.

DMARDs and Their Function

DMARDs work by targeting the underlying immunological processes that drive inflammatory arthritis, especially rheumatoid arthritis. Their mechanisms are diverse, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of the disease process.

1. Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs):

- Methotrexate:

Methotrexate is the cornerstone of RA treatment. It functions primarily as an antimetabolite, inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase and thereby impairing the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. In addition to these anti-proliferative effects, methotrexate enhances the release of adenosine, a potent anti-inflammatory mediator, which helps reduce synovial inflammation and subsequent joint damage.

- Sulfasalazine, Hydroxychloroquine, and Others:

Other csDMARDs work through various mechanisms including inhibition of cytokine production, modulation of immune cell function, or interference with antigen presentation. These agents help reduce systemic inflammation and can slow joint erosion over time.

2. Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs):

These agents are typically monoclonal antibodies or receptor constructs that specifically target inflammatory mediators. For instance:

- TNF-α Inhibitors:

Drugs like etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab bind to TNF-α, a critical cytokine in RA pathogenesis, thereby neutralizing its effects. This targeted approach can lead to reduced synovial inflammation and preservation of joint structure over the long term.

- Interleukin Inhibitors:

Agents targeting interleukins such as IL-6 (e.g., tocilizumab) help in controlling the inflammatory cascade by blocking cytokine signaling. These drugs have shown efficacy not only in reducing pain and swelling but also in impeding the progression of joint damage.

3. Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs):

These are small-molecule inhibitors of intracellular signaling pathways, such as the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, that mediate cytokine signal transduction. By blocking the JAK-STAT pathway, these drugs reduce the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes and provide clinical improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Effectiveness and Considerations

While understanding the underlying mechanisms is critical, it is equally important to consider the clinical efficacy, potential side effects, and patient-specific factors that guide the choice of treatment. A comparative analysis helps in selecting the most appropriate agent or combination of agents for individual patients.

Clinical Efficacy

The clinical efficacy of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs has been extensively studied across various trials and meta-analyses.

1. NSAIDs:

NSAIDs are effective at reducing pain symptoms and improving joint function in knee arthritis, particularly in osteoarthritis. Network meta-analyses have shown that topical NSAIDs can provide a similar degree of pain relief compared to oral preparations, with the added advantage of fewer systemic side effects. Nonetheless, the degree of pain reduction is generally modest and primarily addresses the symptoms rather than altering the underlying disease progression.

2. Corticosteroids:

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections yield rapid pain relief and functional improvement for acute exacerbations of knee arthritis. The benefit is typically observed in the short-term (up to six weeks), after which the effects of a single injection may wane. Some studies have noted a significant increase in cartilage volume loss with repeated use over extended periods, highlighting the need for caution. Their efficacy in providing immediate symptomatic relief makes them indispensable in managing severe flare-ups, even though they may not be ideal for long-term disease modification.

3. DMARDs:

The primary efficacy of DMARDs lies in their ability to slow disease progression, particularly in inflammatory forms of arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis. csDMARDs like methotrexate are often used as first-line agents and have demonstrated a significant impact on reducing disease activity and halting joint erosions. The targeted nature of bDMARDs has led to improvements in both clinical and radiological outcomes, significantly altering the disease course when used timely. While DMARDs may take several weeks to months to exhibit full effects, their long-term benefits in terms of joint preservation and reduction in disability are well established.

Side Effects and Risks

Each class of drugs carries its own risk profile, which must be weighed against their benefits in individual patient scenarios.

1. NSAIDs:

The common adverse effects associated with NSAIDs include gastrointestinal irritation, peptic ulcer formation, renal impairment, and an increased risk for cardiovascular events. Nonselective NSAIDs inhibit COX-1, which disrupts gastric mucosal protection and platelet function, leading to these complications. COX-2 inhibitors have a more favorable gastrointestinal safety profile but may still carry cardiovascular risks. Topical formulations have been introduced to mitigate these risks by reducing systemic drug exposure while maintaining local efficacy.

2. Corticosteroids:

Although corticosteroids are highly effective for short-term use, their adverse effects are well documented. Repeated intra-articular injections can lead to joint cartilage degradation, local soft tissue atrophy, and systemic absorption that, in some cases, may result in hyperglycemia or immunosuppression. The risk of joint damage with long-term use necessitates their cautious application and often limits the frequency of injections to avoid compromising joint integrity.

3. DMARDs:

DMARDs have a different profile of adverse effects, often related to their immunosuppressive properties. For example, methotrexate can cause gastrointestinal disturbances, hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and mucosal ulcers. Regular monitoring of liver function and blood counts is necessary during treatment. Biologic DMARDs, while highly efficacious, are associated with risks such as an increased susceptibility to infections (including opportunistic infections) and rarely the development of malignancies, necessitating careful patient selection and surveillance. Newer targeted synthetic DMARDs may also have unique side effects such as laboratory abnormalities and increased risk of thromboembolism, requiring individualized risk assessment before and during therapy.

Patient-Specific Considerations

The management strategy for knee arthritis must be tailored to the individual patient considering multiple factors such as age, comorbidities, disease severity, and patient preferences.

1. Age and Comorbidities:

Older patients or those with a history of cardiovascular, renal, or gastrointestinal disorders may benefit from topical NSAIDs or cautious dosing of oral agents to minimize systemic adverse effects. The selection of DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis also considers patient age and existing comorbid conditions, as these factors may influence the risk of adverse events such as infections or liver toxicity.

2. Disease Severity and Phenotype:

In patients with mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis, NSAIDs and supportive measures such as exercise and weight management may suffice. However, in cases with inflammatory phenotypes, especially in rheumatoid arthritis, the use of DMARDs—often in combination with short-term corticosteroids—may be necessary to control the disease process and prevent structural joint damage. For individuals experiencing acute flare-ups, an intra-articular corticosteroid injection can provide rapid symptomatic relief before longer-term therapies take effect.

3. Patient Preferences and Lifestyle Considerations:

The route of administration, potential side effects, and treatment duration are key factors influencing patient adherence. Some patients may prefer topical applications due to a lower systemic risk profile, whereas others might be more amenable to intra-articular injections if rapid relief is desired. Additionally, the cost and availability of medications, especially advanced biologic agents, play an important role in the decision-making process, particularly in healthcare systems with limited resources.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the treatment of knee arthritis with pharmacological agents involves a complex interplay between addressing acute symptoms and modifying the disease course in the long term. NSAIDs provide rapid and effective symptomatic relief through the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by blocking the COX enzymes. They are effective in reducing pain and inflammation, but their safety profile is heavily influenced by the selectivity of COX inhibition and the formulation used, with topical NSAIDs emerging as a safer alternative for at-risk populations.

Corticosteroids, with their broad anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions, are particularly valuable in acute flare-ups of knee arthritis. By modulating gene transcription and cytokine production, they achieve rapid pain reduction and decrease joint inflammation. However, their potential for joint damage with repeated or long-term use necessitates judicious application, favoring their use in short-term scenarios or as bridging therapy.

DMARDs represent the cornerstone for altering disease progression in inflammatory arthritis. Through various mechanisms—including inhibiting cytokine production, modulating immune cell function, and interfering with intracellular signaling pathways—DMARDs such as methotrexate and biologic agents have revolutionized the management of rheumatoid arthritis, offering long-term benefits in joint preservation and functional improvement. Their use is complemented by the need for careful monitoring and individualized patient assessment to balance efficacy and safety.

From a general perspective, the pharmacological management of knee arthritis is a dynamic field where therapeutic choices are guided by a careful assessment of clinical efficacy, side effect profiles, and patient-specific factors. On a specific level, the mechanistic differences between NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs underscore the need to align treatment strategies with the stage, severity, and type of arthritis. Finally, on a general level, the selection of appropriate drug therapies reflects the necessity to manage pain and inflammation effectively while minimizing adverse effects and improving overall long-term outcomes for patients.

The integration of these perspectives into clinical practice allows for a more nuanced and individualized approach to the treatment of knee arthritis. Ultimately, treatment success depends on the clinician’s ability to balance the symptomatic benefits with potential risks and to adjust the therapeutic regimen according to the evolving needs of the patient. As ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of disease mechanisms and drug action, further improvements in both pharmacological efficacy and safety are anticipated, leading to better patient outcomes and quality of life.

In summary, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs each play distinct yet complementary roles in the management of knee arthritis. NSAIDs are best suited for immediate symptom relief, corticosteroids for rapid control of acute exacerbations, and DMARDs for long-term disease modification in inflammatory arthritis—all while being mindful of their respective side effect profiles and patient-specific considerations. This multimodal strategy forms the basis of contemporary therapy for knee arthritis and provides a framework for individualized treatment planning that is essential for optimizing clinical outcomes.

Knee arthritis is a chronic, degenerative joint disease that affects the articular structures of the knee, including the cartilage, subchondral bone, ligaments, and synovial membrane. It is characterized by progressive joint degeneration, leading to pain, stiffness, and functional impairment. Over time, these changes may culminate in joint instability and significant disability, profoundly affecting quality of life.

Types and SymptomsKnee arthritisis encompasses several clinical entities. The most common is osteoarthritis, often termed degenerative joint disease, where the cumulative effect of mechanical stress on the joint and biological aging results in cartilage degradation and bone spur formation. In contrast, rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic autoimmune condition that causes inflammation primarily of the synovium, leading to joint destruction and extra-articular manifestations. Other variants include post-traumatic arthritis, which ensues after joint injury, and secondary arthritis resulting from metabolic or other systemic conditions. Clinically, patients present with joint pain which is typically worsened by activity and relieved by rest, morning stiffness that usually improves within 30 minutes, and a reduction in range of motion. Some patients may also experience joint swelling, crepitus, and occasional episodes of acute inflammation.

Prevalence and Impact

Knee arthritis is increasingly prevalent worldwide, particularly among the elderly and those with obesity, where the cumulative biomechanical stress and inflammatory milieu accelerate joint degeneration. Recent epidemiological data indicate that approximately 40% of individuals over 65 years suffer from symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, and osteoarthritis is a leading cause of disability and reduced mobility in older populations. The impact is not only clinical—with patients experiencing chronic pain and decreased function—but also socioeconomic, as it often results in a loss of work productivity, increased healthcare utilization, and the need for joint replacement surgeries when the disease progresses to its end stage.

Drug Classes for Knee Arthritis

Managing knee arthritis, particularly osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, typically involves a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Among the pharmacological treatments, three key drug classes are most commonly used: Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), Corticosteroids, and Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs). Each class works via a different mechanism of action, targets varied inflammatory pathways, and offers distinct benefits and pitfalls depending on the clinical scenario.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are widely prescribed to alleviate the pain and inflammation associated with knee arthritis. They are often the first-line therapy in many clinical guidelines, ensuring that patients obtain rapid, symptomatic relief. These drugs are available in oral, topical, and sometimes injectable formulations. The efficacy of NSAIDs has been established through numerous randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. They are particularly valued because of their dual action: reducing pain perception by inhibiting inflammatory mediators and diminishing the overall inflammatory process in the joint. However, while NSAIDs offer significant pain relief, their use is often limited by concerns regarding systemic adverse effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiovascular events, and renal impairment, especially with long-term use. Recent comparisons have also shown that while topical NSAIDs provide similar efficacy to oral agents, they tend to have a better safety profile in high-risk populations.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, particularly when administered via intra-articular injection, are used primarily for short-term relief of acute flare-ups in knee arthritis. These potent anti-inflammatory agents act more broadly on the inflammatory cascade compared to NSAIDs. They suppress the inflammatory response not only by inhibiting enzymes and pathways similar to those targeted by NSAIDs but also by modulating immune cell function and cytokine production on a genomic level. In clinical practice, intra-articular corticosteroid injections are often employed when oral agents fail to control acute exacerbations, providing rapid pain relief that may last for several weeks. Despite their potent local anti-inflammatory effects, systemic absorption can occur with repeated injections, and there is a possibility of long-term deleterious effects on the joint structures, such as cartilage thinning or damage with excessive use over time.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)

DMARDs represent a heterogeneous group of medications that are used not only to alleviate symptoms but also to impede the progressive joint destruction characteristic of inflammatory arthritis, most notably rheumatoid arthritis. DMARDs are subdivided into conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine, and biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), which include agents targeting tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins, and other specific immune pathways. In recent years, targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) have also emerged. These drugs provide a disease-modifying effect by inhibiting specific mediators of inflammation and immune response at the cellular and molecular levels, thereby reducing synovial inflammation, decelerating structural joint damage, and maintaining joint function over the long term. DMARD therapy is especially critical in rheumatoid arthritis, where controlling the immune-mediated inflammatory process can prevent irreversible joint destructions and systemic complications.

Mechanisms of Action

The way in which these drug classes work to alleviate symptoms and alter the disease course in knee arthritis is rooted in their distinct biochemical and cellular mechanisms. Understanding these mechanisms helps clinicians tailor therapy according to the severity of the disease, patient comorbidities, and the risk–benefit profile.

How NSAIDs Work

NSAIDs exert their therapeutic effects predominantly by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes—COX-1 and COX-2. These enzymes catalyze the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, which are key mediators of inflammation, pain, and fever.

1. Inhibition of Prostaglandin Synthesis:

By blocking COX activity, NSAIDs reduce the synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a mediator responsible for pain sensitization, vasodilation, and inflammatory responses. This biochemical inhibition leads to a decrease in both the pain sensation and the inflammatory process within the joint.

2. Selective Versus Nonselective Inhibition:

Traditional NSAIDs inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2. Inhibition of COX-1 is associated with adverse gastrointestinal and renal effects because COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues and serves physiological functions such as protecting the gastric mucosa, regulating renal blood flow, and aiding in platelet aggregation. Conversely, COX-2 selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) target the inducible form of the enzyme, which is upregulated during inflammation, thereby offering pain relief with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. However, even COX-2 inhibitors are not without risk, as they have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in some studies.

3. Topical NSAIDs:

The development of topical NSAIDs aims to localize the drug effect to the joint region while minimizing systemic exposure. This formulation delivers sufficient concentration to inhibit local COX activity and reduce pain and inflammation while avoiding many of the systemic adverse effects seen with oral NSAIDs.

Mechanism of Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids work through a different pathway compared to NSAIDs, providing a broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effect by modulating the transcription of numerous genes involved in the inflammatory response.

1. Transcriptional Regulation:

Corticosteroids penetrate the cell membrane and bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the cytoplasm. The steroid–receptor complex then translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) on the DNA. This binding results in upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes and downregulation of pro-inflammatory genes, including those encoding cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha) as well as enzymes such as COX-2.

2. Inhibition of Cytokine Production:

By reducing the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines along with the inhibition of leukocyte infiltration, corticosteroids effectively blunt the inflammatory cascade. This mechanism is particularly beneficial in dampening the acute inflammatory flare-ups seen in knee arthritis, allowing for rapid symptomatic improvement.

3. Depot Effect with Injections:

When administered intra-articularly, corticosteroids form a depot within the joint space, permitting a slow release of the active agent. This allows for sustained anti-inflammatory activity at the site of pathology for several weeks. However, long-term or repeated injections must be approached with caution as they might lead to joint structural changes such as cartilage thinning or degeneration over time.

DMARDs and Their Function

DMARDs work by targeting the underlying immunological processes that drive inflammatory arthritis, especially rheumatoid arthritis. Their mechanisms are diverse, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of the disease process.

1. Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs):

- Methotrexate:

Methotrexate is the cornerstone of RA treatment. It functions primarily as an antimetabolite, inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase and thereby impairing the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. In addition to these anti-proliferative effects, methotrexate enhances the release of adenosine, a potent anti-inflammatory mediator, which helps reduce synovial inflammation and subsequent joint damage.

- Sulfasalazine, Hydroxychloroquine, and Others:

Other csDMARDs work through various mechanisms including inhibition of cytokine production, modulation of immune cell function, or interference with antigen presentation. These agents help reduce systemic inflammation and can slow joint erosion over time.

2. Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs):

These agents are typically monoclonal antibodies or receptor constructs that specifically target inflammatory mediators. For instance:

- TNF-α Inhibitors:

Drugs like etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab bind to TNF-α, a critical cytokine in RA pathogenesis, thereby neutralizing its effects. This targeted approach can lead to reduced synovial inflammation and preservation of joint structure over the long term.

- Interleukin Inhibitors:

Agents targeting interleukins such as IL-6 (e.g., tocilizumab) help in controlling the inflammatory cascade by blocking cytokine signaling. These drugs have shown efficacy not only in reducing pain and swelling but also in impeding the progression of joint damage.

3. Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs):

These are small-molecule inhibitors of intracellular signaling pathways, such as the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, that mediate cytokine signal transduction. By blocking the JAK-STAT pathway, these drugs reduce the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes and provide clinical improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Effectiveness and Considerations

While understanding the underlying mechanisms is critical, it is equally important to consider the clinical efficacy, potential side effects, and patient-specific factors that guide the choice of treatment. A comparative analysis helps in selecting the most appropriate agent or combination of agents for individual patients.

Clinical Efficacy

The clinical efficacy of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs has been extensively studied across various trials and meta-analyses.

1. NSAIDs:

NSAIDs are effective at reducing pain symptoms and improving joint function in knee arthritis, particularly in osteoarthritis. Network meta-analyses have shown that topical NSAIDs can provide a similar degree of pain relief compared to oral preparations, with the added advantage of fewer systemic side effects. Nonetheless, the degree of pain reduction is generally modest and primarily addresses the symptoms rather than altering the underlying disease progression.

2. Corticosteroids:

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections yield rapid pain relief and functional improvement for acute exacerbations of knee arthritis. The benefit is typically observed in the short-term (up to six weeks), after which the effects of a single injection may wane. Some studies have noted a significant increase in cartilage volume loss with repeated use over extended periods, highlighting the need for caution. Their efficacy in providing immediate symptomatic relief makes them indispensable in managing severe flare-ups, even though they may not be ideal for long-term disease modification.

3. DMARDs:

The primary efficacy of DMARDs lies in their ability to slow disease progression, particularly in inflammatory forms of arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis. csDMARDs like methotrexate are often used as first-line agents and have demonstrated a significant impact on reducing disease activity and halting joint erosions. The targeted nature of bDMARDs has led to improvements in both clinical and radiological outcomes, significantly altering the disease course when used timely. While DMARDs may take several weeks to months to exhibit full effects, their long-term benefits in terms of joint preservation and reduction in disability are well established.

Side Effects and Risks

Each class of drugs carries its own risk profile, which must be weighed against their benefits in individual patient scenarios.

1. NSAIDs:

The common adverse effects associated with NSAIDs include gastrointestinal irritation, peptic ulcer formation, renal impairment, and an increased risk for cardiovascular events. Nonselective NSAIDs inhibit COX-1, which disrupts gastric mucosal protection and platelet function, leading to these complications. COX-2 inhibitors have a more favorable gastrointestinal safety profile but may still carry cardiovascular risks. Topical formulations have been introduced to mitigate these risks by reducing systemic drug exposure while maintaining local efficacy.

2. Corticosteroids:

Although corticosteroids are highly effective for short-term use, their adverse effects are well documented. Repeated intra-articular injections can lead to joint cartilage degradation, local soft tissue atrophy, and systemic absorption that, in some cases, may result in hyperglycemia or immunosuppression. The risk of joint damage with long-term use necessitates their cautious application and often limits the frequency of injections to avoid compromising joint integrity.

3. DMARDs:

DMARDs have a different profile of adverse effects, often related to their immunosuppressive properties. For example, methotrexate can cause gastrointestinal disturbances, hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and mucosal ulcers. Regular monitoring of liver function and blood counts is necessary during treatment. Biologic DMARDs, while highly efficacious, are associated with risks such as an increased susceptibility to infections (including opportunistic infections) and rarely the development of malignancies, necessitating careful patient selection and surveillance. Newer targeted synthetic DMARDs may also have unique side effects such as laboratory abnormalities and increased risk of thromboembolism, requiring individualized risk assessment before and during therapy.

Patient-Specific Considerations

The management strategy for knee arthritis must be tailored to the individual patient considering multiple factors such as age, comorbidities, disease severity, and patient preferences.

1. Age and Comorbidities:

Older patients or those with a history of cardiovascular, renal, or gastrointestinal disorders may benefit from topical NSAIDs or cautious dosing of oral agents to minimize systemic adverse effects. The selection of DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis also considers patient age and existing comorbid conditions, as these factors may influence the risk of adverse events such as infections or liver toxicity.

2. Disease Severity and Phenotype:

In patients with mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis, NSAIDs and supportive measures such as exercise and weight management may suffice. However, in cases with inflammatory phenotypes, especially in rheumatoid arthritis, the use of DMARDs—often in combination with short-term corticosteroids—may be necessary to control the disease process and prevent structural joint damage. For individuals experiencing acute flare-ups, an intra-articular corticosteroid injection can provide rapid symptomatic relief before longer-term therapies take effect.

3. Patient Preferences and Lifestyle Considerations:

The route of administration, potential side effects, and treatment duration are key factors influencing patient adherence. Some patients may prefer topical applications due to a lower systemic risk profile, whereas others might be more amenable to intra-articular injections if rapid relief is desired. Additionally, the cost and availability of medications, especially advanced biologic agents, play an important role in the decision-making process, particularly in healthcare systems with limited resources.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the treatment of knee arthritis with pharmacological agents involves a complex interplay between addressing acute symptoms and modifying the disease course in the long term. NSAIDs provide rapid and effective symptomatic relief through the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by blocking the COX enzymes. They are effective in reducing pain and inflammation, but their safety profile is heavily influenced by the selectivity of COX inhibition and the formulation used, with topical NSAIDs emerging as a safer alternative for at-risk populations.

Corticosteroids, with their broad anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions, are particularly valuable in acute flare-ups of knee arthritis. By modulating gene transcription and cytokine production, they achieve rapid pain reduction and decrease joint inflammation. However, their potential for joint damage with repeated or long-term use necessitates judicious application, favoring their use in short-term scenarios or as bridging therapy.

DMARDs represent the cornerstone for altering disease progression in inflammatory arthritis. Through various mechanisms—including inhibiting cytokine production, modulating immune cell function, and interfering with intracellular signaling pathways—DMARDs such as methotrexate and biologic agents have revolutionized the management of rheumatoid arthritis, offering long-term benefits in joint preservation and functional improvement. Their use is complemented by the need for careful monitoring and individualized patient assessment to balance efficacy and safety.

From a general perspective, the pharmacological management of knee arthritis is a dynamic field where therapeutic choices are guided by a careful assessment of clinical efficacy, side effect profiles, and patient-specific factors. On a specific level, the mechanistic differences between NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs underscore the need to align treatment strategies with the stage, severity, and type of arthritis. Finally, on a general level, the selection of appropriate drug therapies reflects the necessity to manage pain and inflammation effectively while minimizing adverse effects and improving overall long-term outcomes for patients.

The integration of these perspectives into clinical practice allows for a more nuanced and individualized approach to the treatment of knee arthritis. Ultimately, treatment success depends on the clinician’s ability to balance the symptomatic benefits with potential risks and to adjust the therapeutic regimen according to the evolving needs of the patient. As ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of disease mechanisms and drug action, further improvements in both pharmacological efficacy and safety are anticipated, leading to better patient outcomes and quality of life.

In summary, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs each play distinct yet complementary roles in the management of knee arthritis. NSAIDs are best suited for immediate symptom relief, corticosteroids for rapid control of acute exacerbations, and DMARDs for long-term disease modification in inflammatory arthritis—all while being mindful of their respective side effect profiles and patient-specific considerations. This multimodal strategy forms the basis of contemporary therapy for knee arthritis and provides a framework for individualized treatment planning that is essential for optimizing clinical outcomes.

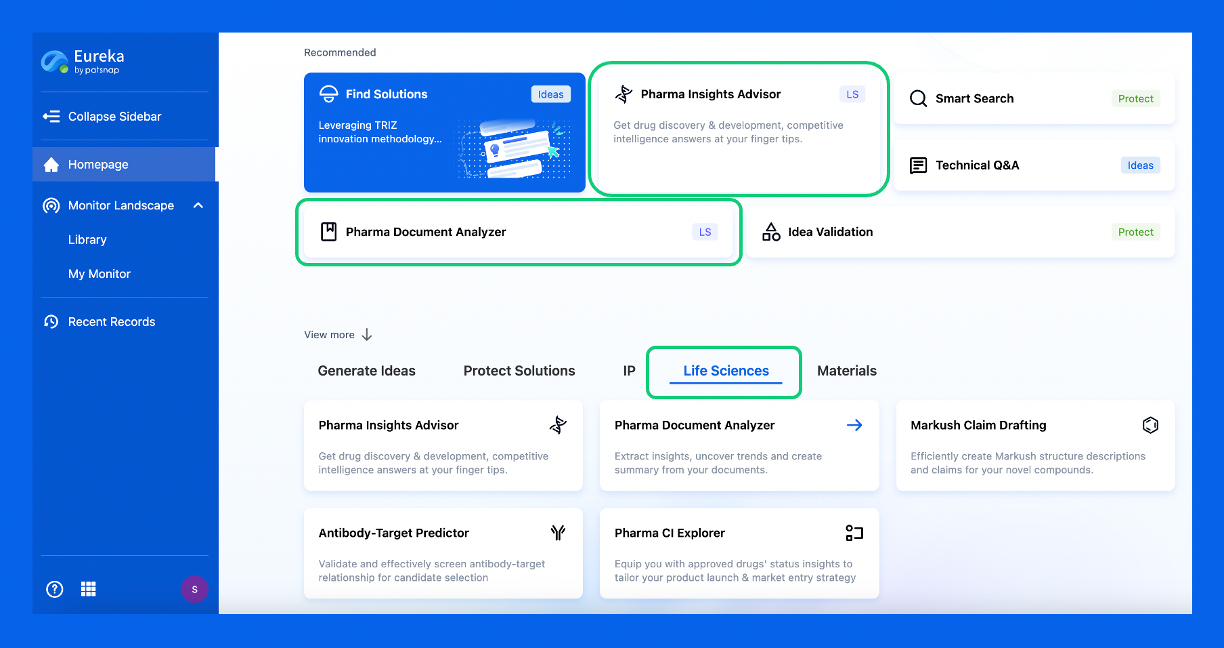

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.