Request Demo

How do different drug classes work in treating ulcerative colitis?

17 March 2025

Overview of Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that predominantly affects the large intestine and is characterized by an unpredictable course marked by periodic flare-ups and remissions. Although the disease is idiopathic, its clinical presentation and underlying pathology have been carefully studied over the last decades.

Definition and Symptoms

UC is defined as a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease of the colonic mucosa with continuous lesions starting in the rectum and extending proximally to variable distances in the colon. Patients with UC commonly experience symptoms such as bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenesmus, urgency, and weight loss. In more severe cases, patients might also develop high fever, severe cramps, and systemic manifestations as a consequence of chronic inflammation. The variability in clinical presentation—from mild intermittent discomfort to severe, life‐threatening episodes—requires a flexible and individualized approach to treatment.

Pathophysiology and Disease Progression

The pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, environmental factors, immune dysregulation, and alterations in the gut microbiome. Within the colonic mucosa, an abnormal immune response leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and activated T lymphocytes. These cells secrete pro‐inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF‑α), interleukin‑1 beta (IL‑1β), IL‑6, and IL‑13, thereby perpetuating a cycle of inflammation that results in mucosal ulceration and impaired barrier function. Over time, ongoing inflammation and epithelial injury may lead to complications such as strictures, dysplasia, and, in some cases, an increased risk of colorectal cancer. This evolving nature of the disease—from initial mucosal injury to chronic inflammation and eventual complications—reinforces the need for therapies that target multiple steps in the pathogenic cascade.

Drug Classes Used in Ulcerative Colitis Treatment

A range of drug classes is now available to treat UC. Each class comes with distinct mechanisms of action and therapeutic roles, which have been honed by years of clinical research and practice. There is a step‐up approach in therapy: initial treatments are usually less aggressive, such as aminosalicylates or corticosteroids, whereas more advanced therapies like immunomodulators, biologics, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are reserved for patients with moderate‐to‐severe disease or those with refractory responses.

Aminosalicylates

Aminosalicylates (also known as 5‑aminosalicylic acid or mesalamine-based agents) represent the conventional backbone treatment for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. They can be formulated as topical agents (suppositories, enemas) for distal disease or as oral formulations with controlled release to target the colon. Their early introduction in the treatment of UC is justified by their safety profile and effectiveness in reducing mucosal inflammation.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are potent anti‑inflammatory medications employed mainly as “rescue” therapies to induce remission in patients with moderate-to-severe flares. They are used for short-term management to blunt the acute inflammatory process while other maintenance therapies are introduced. Systemic steroids (such as prednisone) act rapidly; however, due to their adverse effect profile, long-term use is generally avoided.

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators, including thiopurines (azathioprine and 6‑mercaptopurine) and methotrexate, are used to maintain remission and spare steroids in patients with a relapsing or steroid-dependent course. These drugs modulate the immune response by interfering with nucleotide synthesis (in the case of thiopurines) or by anti-metabolite effects (methotrexate). They have a slower onset of action compared with corticosteroids but are valuable for long-term disease control.

Biologics

Biologic agents, such as monoclonal antibodies, have revolutionized the treatment landscape for moderate-to-severe UC. The first biologics approved for UC were anti‑tumor necrosis factor (anti‑TNF) agents (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab), which directly target key inflammatory cytokines. More recently, integrin antagonists like vedolizumab and interleukin‑12/23 antagonists such as ustekinumab have been introduced. These therapies directly interrupt specific immune signaling pathways and offer a targeted approach to immune modulation with improved outcomes in refractory cases.

Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors

JAK inhibitors represent a new class of small-molecule drugs that target the intracellular Janus kinase signaling pathway. By inhibiting JAK enzymes (especially JAK1), these drugs interfere with the signal transduction of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines simultaneously. Tofacitinib was the first JAK inhibitor approved for UC, with others like upadacitinib also showing promise in clinical trials.

Mechanisms of Action

Understanding the mechanisms of action for each drug class is crucial, as it offers insights into how these therapies not only relieve symptoms but also modify the underlying inflammatory processes in UC.

How Aminosalicylates Work

Aminosalicylates primarily work by exerting local anti-inflammatory effects on the colonic mucosa. The active ingredient, mesalamine, is thought to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes, through interference with the cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase pathways. In addition, mesalamine has antioxidant properties that help neutralize free radicals at the site of inflammation. These drugs are formulated in ways that allow the active compound to be delivered directly to the colon—either through pH-dependent coatings or time-dependent release systems—ensuring maximum local efficacy with minimal systemic absorption and side effects.

Corticosteroids Mechanisms

Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and budesonide, work by binding to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors, which translocate to the cell nucleus and alter gene transcription. This leads to the suppression of inflammatory cytokine production (including TNF‑α, IL‑1, IL‑6, and chemokines), the inhibition of phospholipase A2 (and consequently the arachidonic acid cascade), and the reduction of immune cell migration to inflamed tissue. The net effect is a rapid decrease in inflammation. However, the systemic nature of their action can lead to wide-ranging side effects, particularly when used over the long term.

Immunomodulators Function

Immunomodulators such as thiopurines and methotrexate act over a longer time frame to maintain remission by modulating the immune system. Thiopurines interfere with nucleic acid synthesis, leading to decreased proliferation of T and B lymphocytes, and they induce apoptosis in activated immune cells. This results in a gradual reduction in the chronic inflammatory process. Methotrexate, on the other hand, acts as an anti‑metabolite by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase, thereby disrupting DNA synthesis and cell replication in rapidly dividing immune cells. These agents are particularly useful for patients who are steroid-dependent or who experience frequent relapses, although they require close monitoring due to potential toxicity and long-term adverse effects.

Biologics Mechanisms

Biologic therapies in UC are designed to target specific molecules or cellular pathways implicated in the inflammatory cascade. The mechanisms by which biologics work differ depending on their target:

- Anti-TNF Agents: Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab bind directly to TNF‑α, a central cytokine driving inflammation in UC. By neutralizing TNF‑α, these agents block a key step in the inflammatory cascade, leading to a reduction in inflammatory cell recruitment, decreased cytokine release, and induction of immune cell apoptosis.

- Integrin Antagonists: Vedolizumab targets the α4β7 integrin, which is expressed on gut-homing lymphocytes. By preventing the adhesion of these lymphocytes to mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) on the endothelium, vedolizumab reduces the migration of inflammatory cells into the gut tissue. This mechanism is gut-selective and minimizes systemic immunosuppression.

- Interleukin-12/23 Antagonists: Ustekinumab blocks the p40 subunit shared by interleukin-12 and interleukin-23. These cytokines are key modulators of Th1 and Th17 immune responses. Inhibiting these cytokines helps dampen the aberrant immune response responsible for chronic inflammation in UC.

The specificity of biologics allows for relatively targeted immune suppression, thereby improving clinical outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe UC while often offering a better safety profile compared to broad-spectrum immunosuppressants.

JAK Inhibitors Action

Janus kinase inhibitors act on intracellular signaling pathways rather than extracellular cytokines. By targeting one or more members of the Janus kinase (JAK) family (with JAK1 being a primary focus in UC), these drugs block the signaling of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines that use the JAK-STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway. For example, tofacitinib blocks multiple JAK enzymes, thereby inhibiting the downstream transcription of inflammatory genes involved in immune cell activation. Upadacitinib, a selective JAK1 inhibitor, similarly disrupts cytokine signaling with the aim of reducing inflammation without inducing significant immunogenicity. These inhibitors offer the advantage of oral administration and a rapid onset of action, and they have demonstrated promising efficacy in clinical trials.

Efficacy and Safety Profiles

The relative efficacy and safety of these different drug classes have been evaluated in numerous randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and real-world studies. Comparing these profiles helps clinicians better position each therapy in the treatment algorithm based on disease severity, patient characteristics, and risk factors.

Clinical Efficacy Comparisons

From a clinical efficacy standpoint, aminosalicylates are effective for inducing and maintaining remission in mild to moderate UC, particularly when delivered as topical agents for distal disease. Their role as first-line agents makes them indispensable despite the fact that they might not be enough for more severe cases. Corticosteroids, though highly effective in inducing rapid remission during acute flares, are not suitable for long-term maintenance because of the risk of serious systemic side effects and complications when used chronically.

Immunomodulators offer a bridge between induction and maintenance therapies by providing longer-term control of inflammation with a steroid-sparing effect. However, their onset is slower and their efficacy may vary between individuals; some patients can achieve prolonged remission with thiopurines while others may not benefit as much and require escalation of therapy.

Biologics have transformed the management of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Anti-TNF agents have demonstrated high rates of mucosal healing, clinical remission, and improvement in quality of life in patients who are refractory to conventional therapy. Integrin antagonists like vedolizumab provide a gut-selective mechanism that offers substantial clinical benefits and improved safety outcomes, particularly in reducing systemic immunosuppression. The interleukin‑12/23 antagonist ustekinumab also shows promising efficacy in patients with prior treatment failures.

JAK inhibitors, as newer agents, have shown robust efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission even in patients who have failed biologic therapies. Their ability to rapidly down-regulate multiple cytokines involved in the inflammatory cascade has translated into significant improvements in both clinical and endoscopic measures of disease activity. Overall, when compared in network meta-analyses or head-to-head studies, each drug class offers unique advantages that may be harnessed depending on the patient’s disease characteristics and prior treatment history.

Side Effects and Safety Concerns

Each drug class comes with its own risk–benefit profile. Aminosalicylates are generally well tolerated; however, in some cases, they may be associated with rare adverse effects such as nephrotoxicity when high doses are used.

Corticosteroids are notorious for their wide range of side effects, including weight gain, hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, hypertension, mood changes, and predisposition to infections. While they are effective in the short term, the long-term use of corticosteroids is limited by these adverse effects, necessitating their use only for induction rather than maintenance therapy.

Immunomodulators, primarily thiopurines and methotrexate, carry risks of hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders. The need for regular monitoring of blood counts and liver enzymes is a clear drawback that makes them less appealing for some patients, despite their value in corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Biologic therapies, due to their target specificity, generally offer an improved safety profile compared to traditional immunosuppressants. Nonetheless, anti-TNF agents have been linked to infusion reactions, reactivation of latent tuberculosis, and an increased risk of infections. Integrin antagonists like vedolizumab tend to have more favorable safety profiles because of their gut-selective mechanism, thereby reducing systemic exposure. Interleukin‑12/23 antagonists also show good tolerability; however, long-term safety data continue to be accrued, and vigilance for rare adverse events is still warranted.

JAK inhibitors have raised some specific concerns regarding safety. Although they are effective and orally administered, they carry risks of thromboembolic events, herpes zoster reactivation, and dyslipidemia. Recent studies indicate that while these side effects are relatively infrequent, careful patient selection and monitoring are essential, particularly in those with underlying cardiovascular risk factors.

Future Directions and Research

The treatment paradigm for ulcerative colitis continues to evolve as new drug classes are introduced and as our understanding of disease pathogenesis deepens. Ongoing research is driven by the need to overcome the current “therapeutic ceiling” and to optimize long-term outcomes.

Emerging Therapies

Several novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation to address the unmet needs in UC management. Emerging therapies include:

- New Janus Kinase Inhibitors: Beyond tofacitinib and upadacitinib, there is ongoing research into more selective JAK inhibitors that may offer enhanced safety profiles by targeting specific JAK family members without broadly suppressing the immune system.

- Other Small-Molecule Agents: Research into small-molecule drugs with improved pharmacokinetic properties continues. These agents may target various pathways involved in inflammation, such as specific kinases (e.g., those mentioned in patents) or other intracellular signaling molecules.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) and Microbiome-Based Therapies: Innovative approaches leverage the modulation of the gut microbiota. Patents describe methods and compositions based on fecal bacteria that correlate with treatment success or failure. These strategies could help restore the microbial balance and reduce inflammation through mechanisms that are distinct from classical anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Combination Therapy Strategies: Combining agents from different classes (for example, biologics with immunomodulators or FMT with conventional drugs) is also an area of active investigation. Combination therapy may address the shortcomings of monotherapy, particularly in refractory cases. Recent clinical trials have explored sequential and simultaneous treatment regimens to optimize both efficacy and safety.

- Novel Cytokine-Targeted Approaches: Beyond TNF and IL-12/23 blockade, novel targets such as interleukin‑17/IL‑23 axis modulation and anti‑integrin therapeutics are being examined further. These therapies aim to provide more personalized targeting based on the unique cytokine profiles of individual patients.

Research Gaps and Opportunities

Despite significant advancements, several research gaps persist:

- Biomarker Discovery and Stratification: One of the major challenges is the identification of reliable biomarkers to predict which patients will respond to a specific therapy. Biomarker-driven stratification could lead to personalized treatment algorithms, minimizing trial-and-error approaches and reducing time to effective remission.

- Long-term Safety Data: As many of the newer agents such as JAK inhibitors and biologics are integrated into clinical practice, long-term safety data remain limited. Ongoing registries and real-world studies are essential to better characterize the safety profiles of these agents, particularly regarding infection risks, cardiovascular events, and malignancy.

- Head-to-Head Trials: Although numerous randomized controlled trials have individually demonstrated the efficacy of different drug classes, there is a scarcity of direct comparison studies. Head-to-head trials would provide clearer guidance on treatment sequencing and allow for more precise positioning of drugs within the therapeutic algorithm.

- Resistance Mechanisms and Loss of Response: Understanding why some patients exhibit primary non-response or secondary loss of response to biologics or other therapies is another critical area. Research into the molecular mechanisms underlying treatment resistance can inform the development of next-generation agents designed to overcome these limitations.

- Integration of Microbiome Research: The role of the gut microbiota in UC is increasingly recognized. However, integrating microbiome-based therapies into mainstream treatment protocols is still in its infancy. Future research will need to address issues related to donor selection, formulation standardization, and long-term impacts on the host immune response.

- Combination and Sequential Therapy: Optimizing combination therapy remains a key area for investigation. Research must elucidate the optimal timing and sequencing of different drug classes to maximize therapeutic benefits while minimizing cumulative toxicity.

Detailed and Explicit Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of ulcerative colitis involves multiple drug classes, each working through distinct mechanisms to restore colonic homeostasis and suppress the inflammatory process. Aminosalicylates act at the local level by inhibiting pro-inflammatory mediators and providing antioxidant effects, making them the first line of therapy for mild-to-moderate disease. Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory agents that rapidly induce remission by altering gene transcription and suppressing cytokine production, although their use is limited by systemic side effects when used long-term. Immunomodulators such as thiopurines and methotrexate offer a slower onset of action but provide sustained immunosuppression through interference with nucleic acid synthesis and cell proliferation. Biologic therapies, including anti-TNF agents, integrin antagonists, and IL‑12/23 inhibitors, target specific components of the immune system and have significantly improved outcomes in moderate-to-severe UC by reducing inflammation and promoting mucosal healing. Finally, Janus kinase inhibitors represent an innovative oral therapeutic option that blocks multiple cytokine signaling pathways via the JAK-STAT cascade, thereby reducing inflammatory gene transcription.

Efficacy comparisons suggest that while aminosalicylates remain highly effective for early-stage disease control, corticosteroids are indispensable for acute flares, and more aggressive agents such as immunomodulators and biologics are necessary for chronic or refractory disease. Safety concerns vary by class—with corticosteroids and immunomodulators carrying risks related to systemic side effects, while biologics and JAK inhibitors, although more targeted, require vigilant monitoring for infections, thromboembolic events, and other adverse reactions.

Future research is poised to further refine treatment strategies through personalized medicine approaches, including biomarker development, combination and sequential therapy studies, and the integration of microbiome-based therapies. Advances in the understanding of the disease’s molecular underpinnings hold the prospect of new targets and therapeutic agents that may break through the current therapeutic ceiling, offering hope for improved long-term outcomes and quality of life for patients with ulcerative colitis.

By synthesizing data from a broad spectrum of clinical trials, regulatory reviews, and innovative patents, we gain an appreciation of the multifaceted approach needed to treat UC effectively. Each drug class plays a critical role in a step-wise therapeutic algorithm designed to tailor treatment to individual patient needs, emphasizing a balance between rapid symptom relief and long-term disease control. The evolving landscape of UC treatment is a testament to decades of research and clinical practice, and continued innovation is essential for addressing the remaining challenges in achieving durable remission and preventing disease progression.

This comprehensive understanding not only informs current clinical practice but also paves the way toward more personalized, effective, and safer therapies in the future. The integration of advanced mechanisms, robust clinical efficacy data, and strategic safety monitoring will ultimately lead to improved outcomes for patients suffering from this debilitating disease.

Through a general-specific-general approach, we can conclude that successful treatment of ulcerative colitis requires a nuanced application of multiple therapeutic modalities. First, a general understanding of the disease lays the foundation for selecting the appropriate drug class; specific mechanisms of action then provide the rationale for their use in different clinical scenarios; and a general overview of efficacy and safety profiles guides clinicians in making informed, patient-centered decisions. With future research focusing on emerging modalities and personalized treatment strategies, the promise of achieving remission and long-term disease control in UC patients becomes ever more attainable.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that predominantly affects the large intestine and is characterized by an unpredictable course marked by periodic flare-ups and remissions. Although the disease is idiopathic, its clinical presentation and underlying pathology have been carefully studied over the last decades.

Definition and Symptoms

UC is defined as a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease of the colonic mucosa with continuous lesions starting in the rectum and extending proximally to variable distances in the colon. Patients with UC commonly experience symptoms such as bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenesmus, urgency, and weight loss. In more severe cases, patients might also develop high fever, severe cramps, and systemic manifestations as a consequence of chronic inflammation. The variability in clinical presentation—from mild intermittent discomfort to severe, life‐threatening episodes—requires a flexible and individualized approach to treatment.

Pathophysiology and Disease Progression

The pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, environmental factors, immune dysregulation, and alterations in the gut microbiome. Within the colonic mucosa, an abnormal immune response leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and activated T lymphocytes. These cells secrete pro‐inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF‑α), interleukin‑1 beta (IL‑1β), IL‑6, and IL‑13, thereby perpetuating a cycle of inflammation that results in mucosal ulceration and impaired barrier function. Over time, ongoing inflammation and epithelial injury may lead to complications such as strictures, dysplasia, and, in some cases, an increased risk of colorectal cancer. This evolving nature of the disease—from initial mucosal injury to chronic inflammation and eventual complications—reinforces the need for therapies that target multiple steps in the pathogenic cascade.

Drug Classes Used in Ulcerative Colitis Treatment

A range of drug classes is now available to treat UC. Each class comes with distinct mechanisms of action and therapeutic roles, which have been honed by years of clinical research and practice. There is a step‐up approach in therapy: initial treatments are usually less aggressive, such as aminosalicylates or corticosteroids, whereas more advanced therapies like immunomodulators, biologics, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are reserved for patients with moderate‐to‐severe disease or those with refractory responses.

Aminosalicylates

Aminosalicylates (also known as 5‑aminosalicylic acid or mesalamine-based agents) represent the conventional backbone treatment for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. They can be formulated as topical agents (suppositories, enemas) for distal disease or as oral formulations with controlled release to target the colon. Their early introduction in the treatment of UC is justified by their safety profile and effectiveness in reducing mucosal inflammation.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are potent anti‑inflammatory medications employed mainly as “rescue” therapies to induce remission in patients with moderate-to-severe flares. They are used for short-term management to blunt the acute inflammatory process while other maintenance therapies are introduced. Systemic steroids (such as prednisone) act rapidly; however, due to their adverse effect profile, long-term use is generally avoided.

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators, including thiopurines (azathioprine and 6‑mercaptopurine) and methotrexate, are used to maintain remission and spare steroids in patients with a relapsing or steroid-dependent course. These drugs modulate the immune response by interfering with nucleotide synthesis (in the case of thiopurines) or by anti-metabolite effects (methotrexate). They have a slower onset of action compared with corticosteroids but are valuable for long-term disease control.

Biologics

Biologic agents, such as monoclonal antibodies, have revolutionized the treatment landscape for moderate-to-severe UC. The first biologics approved for UC were anti‑tumor necrosis factor (anti‑TNF) agents (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab), which directly target key inflammatory cytokines. More recently, integrin antagonists like vedolizumab and interleukin‑12/23 antagonists such as ustekinumab have been introduced. These therapies directly interrupt specific immune signaling pathways and offer a targeted approach to immune modulation with improved outcomes in refractory cases.

Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors

JAK inhibitors represent a new class of small-molecule drugs that target the intracellular Janus kinase signaling pathway. By inhibiting JAK enzymes (especially JAK1), these drugs interfere with the signal transduction of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines simultaneously. Tofacitinib was the first JAK inhibitor approved for UC, with others like upadacitinib also showing promise in clinical trials.

Mechanisms of Action

Understanding the mechanisms of action for each drug class is crucial, as it offers insights into how these therapies not only relieve symptoms but also modify the underlying inflammatory processes in UC.

How Aminosalicylates Work

Aminosalicylates primarily work by exerting local anti-inflammatory effects on the colonic mucosa. The active ingredient, mesalamine, is thought to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes, through interference with the cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase pathways. In addition, mesalamine has antioxidant properties that help neutralize free radicals at the site of inflammation. These drugs are formulated in ways that allow the active compound to be delivered directly to the colon—either through pH-dependent coatings or time-dependent release systems—ensuring maximum local efficacy with minimal systemic absorption and side effects.

Corticosteroids Mechanisms

Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and budesonide, work by binding to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors, which translocate to the cell nucleus and alter gene transcription. This leads to the suppression of inflammatory cytokine production (including TNF‑α, IL‑1, IL‑6, and chemokines), the inhibition of phospholipase A2 (and consequently the arachidonic acid cascade), and the reduction of immune cell migration to inflamed tissue. The net effect is a rapid decrease in inflammation. However, the systemic nature of their action can lead to wide-ranging side effects, particularly when used over the long term.

Immunomodulators Function

Immunomodulators such as thiopurines and methotrexate act over a longer time frame to maintain remission by modulating the immune system. Thiopurines interfere with nucleic acid synthesis, leading to decreased proliferation of T and B lymphocytes, and they induce apoptosis in activated immune cells. This results in a gradual reduction in the chronic inflammatory process. Methotrexate, on the other hand, acts as an anti‑metabolite by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase, thereby disrupting DNA synthesis and cell replication in rapidly dividing immune cells. These agents are particularly useful for patients who are steroid-dependent or who experience frequent relapses, although they require close monitoring due to potential toxicity and long-term adverse effects.

Biologics Mechanisms

Biologic therapies in UC are designed to target specific molecules or cellular pathways implicated in the inflammatory cascade. The mechanisms by which biologics work differ depending on their target:

- Anti-TNF Agents: Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab bind directly to TNF‑α, a central cytokine driving inflammation in UC. By neutralizing TNF‑α, these agents block a key step in the inflammatory cascade, leading to a reduction in inflammatory cell recruitment, decreased cytokine release, and induction of immune cell apoptosis.

- Integrin Antagonists: Vedolizumab targets the α4β7 integrin, which is expressed on gut-homing lymphocytes. By preventing the adhesion of these lymphocytes to mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) on the endothelium, vedolizumab reduces the migration of inflammatory cells into the gut tissue. This mechanism is gut-selective and minimizes systemic immunosuppression.

- Interleukin-12/23 Antagonists: Ustekinumab blocks the p40 subunit shared by interleukin-12 and interleukin-23. These cytokines are key modulators of Th1 and Th17 immune responses. Inhibiting these cytokines helps dampen the aberrant immune response responsible for chronic inflammation in UC.

The specificity of biologics allows for relatively targeted immune suppression, thereby improving clinical outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe UC while often offering a better safety profile compared to broad-spectrum immunosuppressants.

JAK Inhibitors Action

Janus kinase inhibitors act on intracellular signaling pathways rather than extracellular cytokines. By targeting one or more members of the Janus kinase (JAK) family (with JAK1 being a primary focus in UC), these drugs block the signaling of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines that use the JAK-STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway. For example, tofacitinib blocks multiple JAK enzymes, thereby inhibiting the downstream transcription of inflammatory genes involved in immune cell activation. Upadacitinib, a selective JAK1 inhibitor, similarly disrupts cytokine signaling with the aim of reducing inflammation without inducing significant immunogenicity. These inhibitors offer the advantage of oral administration and a rapid onset of action, and they have demonstrated promising efficacy in clinical trials.

Efficacy and Safety Profiles

The relative efficacy and safety of these different drug classes have been evaluated in numerous randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and real-world studies. Comparing these profiles helps clinicians better position each therapy in the treatment algorithm based on disease severity, patient characteristics, and risk factors.

Clinical Efficacy Comparisons

From a clinical efficacy standpoint, aminosalicylates are effective for inducing and maintaining remission in mild to moderate UC, particularly when delivered as topical agents for distal disease. Their role as first-line agents makes them indispensable despite the fact that they might not be enough for more severe cases. Corticosteroids, though highly effective in inducing rapid remission during acute flares, are not suitable for long-term maintenance because of the risk of serious systemic side effects and complications when used chronically.

Immunomodulators offer a bridge between induction and maintenance therapies by providing longer-term control of inflammation with a steroid-sparing effect. However, their onset is slower and their efficacy may vary between individuals; some patients can achieve prolonged remission with thiopurines while others may not benefit as much and require escalation of therapy.

Biologics have transformed the management of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Anti-TNF agents have demonstrated high rates of mucosal healing, clinical remission, and improvement in quality of life in patients who are refractory to conventional therapy. Integrin antagonists like vedolizumab provide a gut-selective mechanism that offers substantial clinical benefits and improved safety outcomes, particularly in reducing systemic immunosuppression. The interleukin‑12/23 antagonist ustekinumab also shows promising efficacy in patients with prior treatment failures.

JAK inhibitors, as newer agents, have shown robust efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission even in patients who have failed biologic therapies. Their ability to rapidly down-regulate multiple cytokines involved in the inflammatory cascade has translated into significant improvements in both clinical and endoscopic measures of disease activity. Overall, when compared in network meta-analyses or head-to-head studies, each drug class offers unique advantages that may be harnessed depending on the patient’s disease characteristics and prior treatment history.

Side Effects and Safety Concerns

Each drug class comes with its own risk–benefit profile. Aminosalicylates are generally well tolerated; however, in some cases, they may be associated with rare adverse effects such as nephrotoxicity when high doses are used.

Corticosteroids are notorious for their wide range of side effects, including weight gain, hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, hypertension, mood changes, and predisposition to infections. While they are effective in the short term, the long-term use of corticosteroids is limited by these adverse effects, necessitating their use only for induction rather than maintenance therapy.

Immunomodulators, primarily thiopurines and methotrexate, carry risks of hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders. The need for regular monitoring of blood counts and liver enzymes is a clear drawback that makes them less appealing for some patients, despite their value in corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Biologic therapies, due to their target specificity, generally offer an improved safety profile compared to traditional immunosuppressants. Nonetheless, anti-TNF agents have been linked to infusion reactions, reactivation of latent tuberculosis, and an increased risk of infections. Integrin antagonists like vedolizumab tend to have more favorable safety profiles because of their gut-selective mechanism, thereby reducing systemic exposure. Interleukin‑12/23 antagonists also show good tolerability; however, long-term safety data continue to be accrued, and vigilance for rare adverse events is still warranted.

JAK inhibitors have raised some specific concerns regarding safety. Although they are effective and orally administered, they carry risks of thromboembolic events, herpes zoster reactivation, and dyslipidemia. Recent studies indicate that while these side effects are relatively infrequent, careful patient selection and monitoring are essential, particularly in those with underlying cardiovascular risk factors.

Future Directions and Research

The treatment paradigm for ulcerative colitis continues to evolve as new drug classes are introduced and as our understanding of disease pathogenesis deepens. Ongoing research is driven by the need to overcome the current “therapeutic ceiling” and to optimize long-term outcomes.

Emerging Therapies

Several novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation to address the unmet needs in UC management. Emerging therapies include:

- New Janus Kinase Inhibitors: Beyond tofacitinib and upadacitinib, there is ongoing research into more selective JAK inhibitors that may offer enhanced safety profiles by targeting specific JAK family members without broadly suppressing the immune system.

- Other Small-Molecule Agents: Research into small-molecule drugs with improved pharmacokinetic properties continues. These agents may target various pathways involved in inflammation, such as specific kinases (e.g., those mentioned in patents) or other intracellular signaling molecules.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) and Microbiome-Based Therapies: Innovative approaches leverage the modulation of the gut microbiota. Patents describe methods and compositions based on fecal bacteria that correlate with treatment success or failure. These strategies could help restore the microbial balance and reduce inflammation through mechanisms that are distinct from classical anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Combination Therapy Strategies: Combining agents from different classes (for example, biologics with immunomodulators or FMT with conventional drugs) is also an area of active investigation. Combination therapy may address the shortcomings of monotherapy, particularly in refractory cases. Recent clinical trials have explored sequential and simultaneous treatment regimens to optimize both efficacy and safety.

- Novel Cytokine-Targeted Approaches: Beyond TNF and IL-12/23 blockade, novel targets such as interleukin‑17/IL‑23 axis modulation and anti‑integrin therapeutics are being examined further. These therapies aim to provide more personalized targeting based on the unique cytokine profiles of individual patients.

Research Gaps and Opportunities

Despite significant advancements, several research gaps persist:

- Biomarker Discovery and Stratification: One of the major challenges is the identification of reliable biomarkers to predict which patients will respond to a specific therapy. Biomarker-driven stratification could lead to personalized treatment algorithms, minimizing trial-and-error approaches and reducing time to effective remission.

- Long-term Safety Data: As many of the newer agents such as JAK inhibitors and biologics are integrated into clinical practice, long-term safety data remain limited. Ongoing registries and real-world studies are essential to better characterize the safety profiles of these agents, particularly regarding infection risks, cardiovascular events, and malignancy.

- Head-to-Head Trials: Although numerous randomized controlled trials have individually demonstrated the efficacy of different drug classes, there is a scarcity of direct comparison studies. Head-to-head trials would provide clearer guidance on treatment sequencing and allow for more precise positioning of drugs within the therapeutic algorithm.

- Resistance Mechanisms and Loss of Response: Understanding why some patients exhibit primary non-response or secondary loss of response to biologics or other therapies is another critical area. Research into the molecular mechanisms underlying treatment resistance can inform the development of next-generation agents designed to overcome these limitations.

- Integration of Microbiome Research: The role of the gut microbiota in UC is increasingly recognized. However, integrating microbiome-based therapies into mainstream treatment protocols is still in its infancy. Future research will need to address issues related to donor selection, formulation standardization, and long-term impacts on the host immune response.

- Combination and Sequential Therapy: Optimizing combination therapy remains a key area for investigation. Research must elucidate the optimal timing and sequencing of different drug classes to maximize therapeutic benefits while minimizing cumulative toxicity.

Detailed and Explicit Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of ulcerative colitis involves multiple drug classes, each working through distinct mechanisms to restore colonic homeostasis and suppress the inflammatory process. Aminosalicylates act at the local level by inhibiting pro-inflammatory mediators and providing antioxidant effects, making them the first line of therapy for mild-to-moderate disease. Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory agents that rapidly induce remission by altering gene transcription and suppressing cytokine production, although their use is limited by systemic side effects when used long-term. Immunomodulators such as thiopurines and methotrexate offer a slower onset of action but provide sustained immunosuppression through interference with nucleic acid synthesis and cell proliferation. Biologic therapies, including anti-TNF agents, integrin antagonists, and IL‑12/23 inhibitors, target specific components of the immune system and have significantly improved outcomes in moderate-to-severe UC by reducing inflammation and promoting mucosal healing. Finally, Janus kinase inhibitors represent an innovative oral therapeutic option that blocks multiple cytokine signaling pathways via the JAK-STAT cascade, thereby reducing inflammatory gene transcription.

Efficacy comparisons suggest that while aminosalicylates remain highly effective for early-stage disease control, corticosteroids are indispensable for acute flares, and more aggressive agents such as immunomodulators and biologics are necessary for chronic or refractory disease. Safety concerns vary by class—with corticosteroids and immunomodulators carrying risks related to systemic side effects, while biologics and JAK inhibitors, although more targeted, require vigilant monitoring for infections, thromboembolic events, and other adverse reactions.

Future research is poised to further refine treatment strategies through personalized medicine approaches, including biomarker development, combination and sequential therapy studies, and the integration of microbiome-based therapies. Advances in the understanding of the disease’s molecular underpinnings hold the prospect of new targets and therapeutic agents that may break through the current therapeutic ceiling, offering hope for improved long-term outcomes and quality of life for patients with ulcerative colitis.

By synthesizing data from a broad spectrum of clinical trials, regulatory reviews, and innovative patents, we gain an appreciation of the multifaceted approach needed to treat UC effectively. Each drug class plays a critical role in a step-wise therapeutic algorithm designed to tailor treatment to individual patient needs, emphasizing a balance between rapid symptom relief and long-term disease control. The evolving landscape of UC treatment is a testament to decades of research and clinical practice, and continued innovation is essential for addressing the remaining challenges in achieving durable remission and preventing disease progression.

This comprehensive understanding not only informs current clinical practice but also paves the way toward more personalized, effective, and safer therapies in the future. The integration of advanced mechanisms, robust clinical efficacy data, and strategic safety monitoring will ultimately lead to improved outcomes for patients suffering from this debilitating disease.

Through a general-specific-general approach, we can conclude that successful treatment of ulcerative colitis requires a nuanced application of multiple therapeutic modalities. First, a general understanding of the disease lays the foundation for selecting the appropriate drug class; specific mechanisms of action then provide the rationale for their use in different clinical scenarios; and a general overview of efficacy and safety profiles guides clinicians in making informed, patient-centered decisions. With future research focusing on emerging modalities and personalized treatment strategies, the promise of achieving remission and long-term disease control in UC patients becomes ever more attainable.

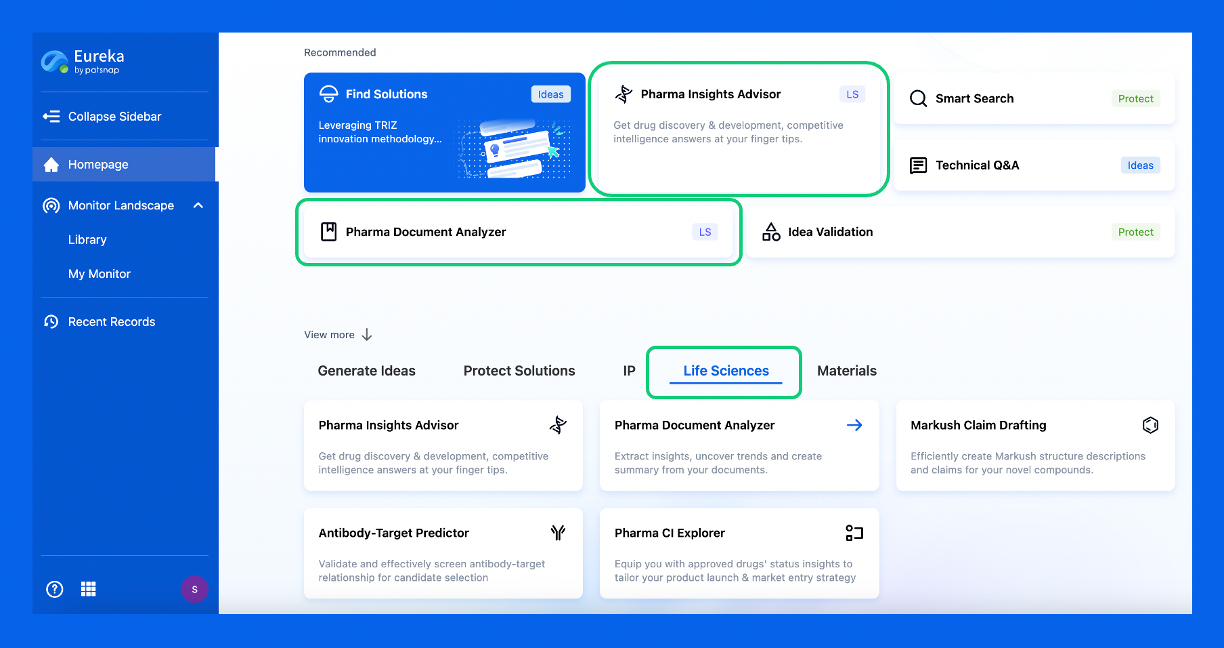

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.