Request Demo

How long does a prescription drug patent last before a generic can be made?

21 March 2025

Introduction to Drug Patents

Definition and Purpose of Drug Patents

Drug patents are a form of intellectual property protection that grant the innovator exclusive rights over a new pharmaceutical compound, formulation, or therapeutic application for a defined period. Their primary purpose is to reward innovation by allowing the patent holder to recoup the exorbitant costs associated with research and development, clinical trials, and regulatory approval. Drug patents are also intended to spur further innovation in drug discovery while ultimately benefiting the public once the patent expires and lower-cost generic versions enter the market. Essentially, these patents establish a temporary monopoly giving the brand‐name manufacturer the right to be the sole producer and seller of the drug, thereby setting the stage for high initial pricing and controlled market dynamics.

Overview of the Patent System in Pharmaceuticals

In the pharmaceutical industry, the patent system plays a crucial role in balancing innovation and public access. By granting exclusive rights for a prescribed duration, the system incentivizes companies to invest billions of dollars in drug innovation. However, the process of obtaining a patent is complex. Patents may cover the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), novel formulations, methods of use, and manufacturing processes. Regulatory frameworks such as the Hatch‐Waxman Act in the U.S. have been introduced to harmonize the interests of drug innovators and generic manufacturers. On one end, innovators secure market exclusivity, and on the other, once exclusivity expires, generic manufacturers are permitted to develop bioequivalent alternatives that are significantly less expensive, greatly expanding patient access and reducing healthcare costs.

Duration and Regulations of Drug Patents

Standard Patent Duration

The standard patent duration for pharmaceuticals, similar to other fields, is typically 20 years from the date of filing. This period is established to create a reasonable timeframe during which patent holders can benefit from their investment in drug development. However, because a significant portion of this 20‐year term is consumed during the lengthy process of drug discovery, preclinical testing, and clinical trials, the effective market life—the period during which the drug is commercially marketed under patent protection—is often much shorter, usually between 10 and 12 years.

For instance, although the legal patent protection lasts 20 years, the effective or available patent life after regulatory approval reflects the time remaining after these extensive developmental and approval phases have been completed. This nuance is pivotal: a drug may accrue only a fraction of the 20 years as effective market exclusivity due to delays inherent in clinical testing and the regulatory review process.

Extensions and Exclusivity Periods

Recognizing the gap between patent filing and market approval, many jurisdictions offer mechanisms to extend the nominal patent term. In the United States, for example, patent term restoration can extend the effective patent life by up to 5 years to compensate for the time lost during regulatory review. This means that while the base patent remains 20 years, specific extensions based on regulatory delays can lead to effective protection periods that are somewhat longer, though they are capped to ensure that patients eventually have access to more affordable alternatives.

Data exclusivity is another regulatory tool that provides market protection independent of patent rights. In the U.S., new chemical entities (NCEs) receive 5 years of data exclusivity, during which generic drug applicants cannot rely on the safety and efficacy data of the originator drug. Similarly, in the European Union and Canada, additional exclusivity periods are granted which may further delay the entry of generics. For biologics, these exclusivity periods are even longer (up to 12 years in the U.S. for biologics).

These extensions and exclusivity periods play a significant role in sustaining the revenue streams for pharmaceutical companies even if the nominal patent term is only 20 years. They ensure that the innovator benefits from a commercially viable period of exclusivity despite the inherent time lags in drug development.

Transition from Patent to Generic

Regulatory Process for Generic Approval

Once a drug’s patent and any regulatory-exclusive rights have expired, generic manufacturers can initiate the process to bring a bioequivalent version to the market. This process is tightly regulated by authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Health Canada. The regulatory pathway for generics typically involves the submission of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), which focuses on demonstrating bioequivalence rather than repeating the extensive clinical trials that were required for the original approval.

The ANDA process is designed to streamline generic drug approval by relying on the safety and efficacy data that were already established for the brand‐name drug. Generic manufacturers must provide evidence that their product has the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration, and that it performs in the body in a manner highly similar to that of the innovator drug.

Furthermore, while the patent on the active ingredient must have expired, other intellectual property protections such as formulation patents or secondary patents regarding delivery mechanisms may still be in place, potentially delaying the entry of generics. Regulatory frameworks have mechanisms in place, such as a “notice of compliance” system and specific timelines (e.g., the 180‐day exclusivity for the first generic challenger in the U.S.), which are intended to balance the rights of both innovator and generic manufacturers.

Criteria for Generic Drug Production

For a generic drug to be approved, it is crucial that the product be pharmaceutically equivalent to the original. Generic manufacturers must demonstrate that the drug's bioavailability—measured through parameters like the maximum concentration (Cmax) and the area under the curve (AUC) in pharmacokinetic studies—is within an acceptable range compared to the originator drug. This criterion of bioequivalence ensures that the generic product will have the same therapeutic effect and safety profile as the brand‐name product, albeit with a few acceptable variances such as differences in excipients or manufacturing processes.

In addition, within the context of international agreements like the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), patent holders must allow the entry of generics after the expiry of protection. Many countries have tailored their regulatory systems to encourage robust scrutiny of documents and ensure that generics adhere to stringent quality standards, thereby ensuring patient safety and consistent treatment outcomes.

Thus, while a 20-year patent nominally protects the drug, the practical ability for a generic manufacturer to bring an equivalent product to market hinges on both the expiration of the patent and all supplementary exclusivity rights, as well as satisfying rigorous regulatory criteria for generic approval.

Impact on the Pharmaceutical Market

Effect on Drug Prices and Accessibility

The expiration of a drug patent is a pivotal market event with significant repercussions for drug prices, accessibility, and, ultimately, public health outcomes. When a patent expires, the exclusive market rights granted to the innovator end, and generic manufacturers can enter the market. This typically leads to a dramatic decrease in drug prices, sometimes resulting in reductions as significant as 40–70% within a few years.

Following patent expiration, price competition intensifies, and healthcare payers, including governments and insurers, benefit from the lower cost of treatment. The decreased prices are primarily due to competition among multiple generic entrants who must offer their products at significantly lower price points compared to the originator to gain market share. In some cases, the shift from brand-name to generic usage can result in price reductions up to 41% after four years, thereby translating into substantial cost savings for the healthcare system and improved patient adherence due to increased affordability.

Moreover, the increase in the number of generic competitors is often associated with a further downward trend in prices and enhanced market penetration. The dynamics of generic competition often result in the brand-name drug’s price falling even before the first generic is marketed, as the innovator may lower its price in anticipation of generic entry to maintain market share.

Ultimately, the availability of generic drugs following patent expiration significantly improves access to essential medicines, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where cost is a critical barrier to treatment. This influx of affordable alternatives not only fosters public health by ensuring broader distribution but also compels policymakers to continuously refine regulatory policies to balance innovation and access effectively.

Case Studies of Major Drugs Transitioning to Generic

Several case studies have illustrated the profound impact of patent expiration on the pharmaceutical market. For example, regulatory and legal strategies have often been employed to extend the market exclusivity of blockbuster drugs, thereby delaying generic entry. In one well-documented case, brand-name manufacturers used legal strategies such as listing multiple patents and initiating litigation to postpone generic market entry for several years, as observed in the litigation around the antidepressant Paxil.

Another scenario involves the phenomenon of authorized generics, where the brand-name manufacturer itself releases a generic version under the same brand name once the patent expires. This practice can sometimes mitigate the loss in revenue and complicate the competitive landscape, as the brand-name company may still capture a substantial share of the market despite the expiration of the initial patent.

In the United States, the Hatch-Waxman Act details a structured approach whereby the first generic applicant may receive 180 days of market exclusivity if successful in challenging the innovator’s patent. This period acts as both an incentive for generic manufacturers to initiate litigation and a mechanism to ensure that competition is eventually introduced into the market. Similar mechanisms are in place in other jurisdictions, although the specifics—such as the duration of exclusivity—vary depending on the country's regulatory framework.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that when generic entry occurs, the overall impact on drug prices is both significant and rapid, leading to enhanced market penetration and reduced costs for consumers. In the Netherlands, for example, a systematic review found that drug prices can decline by approximately 41% within four years after patent expiration, underscoring the critical role that generic competition plays in driving cost efficiencies and expanding treatment access.

Conclusion

In summary, a prescription drug patent typically lasts for 20 years from the date of filing, which is the standard legal duration worldwide. However, by the time the drug undergoes extensive research and clinical testing and receives regulatory approval, the effective period of market exclusivity available to the innovator is often reduced to approximately 10 to 12 years. Regulatory mechanisms such as patent term restoration or extension—allowing up to an additional 5 years in certain jurisdictions—and data exclusivity periods can further adjust this effective duration, prolonging the time before generics can enter the market.

Once the patent and all related exclusivity protections expire, generic manufacturers can enter the market by submitting an ANDA and proving bioequivalence to the originator drug. This process, governed by stringent regulatory frameworks to ensure safety and efficacy, opens the door for significant price reductions and enhanced drug accessibility, as evidenced by numerous case studies and market analyses across regions such as the United States, Europe, and Latin America.

From a broad perspective, the pharmaceutical patent system is designed to stimulate innovation by granting time-limited exclusivity, but it is equally structured to eventually benefit the public through the availability of more affordable generic alternatives. Detailed studies and references from reputable sources such as Synapse reveal that while the nominal patent duration is 20 years, the actual period during which a brand-name drug enjoys near-total market exclusivity is shorter—typically around a decade—after which generics can be made and marketed.

This system, when functioning as intended, helps balance the need for rewarding innovative drug development with the equally important goal of ensuring that life-saving and essential medicines remain accessible and affordable to patients globally. The interplay of patent duration, regulatory extensions, legal strategies like authorized generics, and the rigorous generic approval process collectively shape the dynamics of the pharmaceutical market, influencing both drug prices and patient access.

In conclusion, while the legal patent lasts 20 years, the practical timeframe for market exclusivity is often closer to 10–12 years post-approval, after which generic manufacturers are permitted to produce lower-cost alternatives following carefully regulated processes that ensure therapeutic equivalence and safety. This balanced approach, informed by robust regulatory frameworks, legal provisions, and market dynamics, ultimately serves the dual purpose of fostering pharmaceutical innovation and promoting public health by making drugs more affordable once their patents expire.

Definition and Purpose of Drug Patents

Drug patents are a form of intellectual property protection that grant the innovator exclusive rights over a new pharmaceutical compound, formulation, or therapeutic application for a defined period. Their primary purpose is to reward innovation by allowing the patent holder to recoup the exorbitant costs associated with research and development, clinical trials, and regulatory approval. Drug patents are also intended to spur further innovation in drug discovery while ultimately benefiting the public once the patent expires and lower-cost generic versions enter the market. Essentially, these patents establish a temporary monopoly giving the brand‐name manufacturer the right to be the sole producer and seller of the drug, thereby setting the stage for high initial pricing and controlled market dynamics.

Overview of the Patent System in Pharmaceuticals

In the pharmaceutical industry, the patent system plays a crucial role in balancing innovation and public access. By granting exclusive rights for a prescribed duration, the system incentivizes companies to invest billions of dollars in drug innovation. However, the process of obtaining a patent is complex. Patents may cover the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), novel formulations, methods of use, and manufacturing processes. Regulatory frameworks such as the Hatch‐Waxman Act in the U.S. have been introduced to harmonize the interests of drug innovators and generic manufacturers. On one end, innovators secure market exclusivity, and on the other, once exclusivity expires, generic manufacturers are permitted to develop bioequivalent alternatives that are significantly less expensive, greatly expanding patient access and reducing healthcare costs.

Duration and Regulations of Drug Patents

Standard Patent Duration

The standard patent duration for pharmaceuticals, similar to other fields, is typically 20 years from the date of filing. This period is established to create a reasonable timeframe during which patent holders can benefit from their investment in drug development. However, because a significant portion of this 20‐year term is consumed during the lengthy process of drug discovery, preclinical testing, and clinical trials, the effective market life—the period during which the drug is commercially marketed under patent protection—is often much shorter, usually between 10 and 12 years.

For instance, although the legal patent protection lasts 20 years, the effective or available patent life after regulatory approval reflects the time remaining after these extensive developmental and approval phases have been completed. This nuance is pivotal: a drug may accrue only a fraction of the 20 years as effective market exclusivity due to delays inherent in clinical testing and the regulatory review process.

Extensions and Exclusivity Periods

Recognizing the gap between patent filing and market approval, many jurisdictions offer mechanisms to extend the nominal patent term. In the United States, for example, patent term restoration can extend the effective patent life by up to 5 years to compensate for the time lost during regulatory review. This means that while the base patent remains 20 years, specific extensions based on regulatory delays can lead to effective protection periods that are somewhat longer, though they are capped to ensure that patients eventually have access to more affordable alternatives.

Data exclusivity is another regulatory tool that provides market protection independent of patent rights. In the U.S., new chemical entities (NCEs) receive 5 years of data exclusivity, during which generic drug applicants cannot rely on the safety and efficacy data of the originator drug. Similarly, in the European Union and Canada, additional exclusivity periods are granted which may further delay the entry of generics. For biologics, these exclusivity periods are even longer (up to 12 years in the U.S. for biologics).

These extensions and exclusivity periods play a significant role in sustaining the revenue streams for pharmaceutical companies even if the nominal patent term is only 20 years. They ensure that the innovator benefits from a commercially viable period of exclusivity despite the inherent time lags in drug development.

Transition from Patent to Generic

Regulatory Process for Generic Approval

Once a drug’s patent and any regulatory-exclusive rights have expired, generic manufacturers can initiate the process to bring a bioequivalent version to the market. This process is tightly regulated by authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Health Canada. The regulatory pathway for generics typically involves the submission of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), which focuses on demonstrating bioequivalence rather than repeating the extensive clinical trials that were required for the original approval.

The ANDA process is designed to streamline generic drug approval by relying on the safety and efficacy data that were already established for the brand‐name drug. Generic manufacturers must provide evidence that their product has the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration, and that it performs in the body in a manner highly similar to that of the innovator drug.

Furthermore, while the patent on the active ingredient must have expired, other intellectual property protections such as formulation patents or secondary patents regarding delivery mechanisms may still be in place, potentially delaying the entry of generics. Regulatory frameworks have mechanisms in place, such as a “notice of compliance” system and specific timelines (e.g., the 180‐day exclusivity for the first generic challenger in the U.S.), which are intended to balance the rights of both innovator and generic manufacturers.

Criteria for Generic Drug Production

For a generic drug to be approved, it is crucial that the product be pharmaceutically equivalent to the original. Generic manufacturers must demonstrate that the drug's bioavailability—measured through parameters like the maximum concentration (Cmax) and the area under the curve (AUC) in pharmacokinetic studies—is within an acceptable range compared to the originator drug. This criterion of bioequivalence ensures that the generic product will have the same therapeutic effect and safety profile as the brand‐name product, albeit with a few acceptable variances such as differences in excipients or manufacturing processes.

In addition, within the context of international agreements like the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), patent holders must allow the entry of generics after the expiry of protection. Many countries have tailored their regulatory systems to encourage robust scrutiny of documents and ensure that generics adhere to stringent quality standards, thereby ensuring patient safety and consistent treatment outcomes.

Thus, while a 20-year patent nominally protects the drug, the practical ability for a generic manufacturer to bring an equivalent product to market hinges on both the expiration of the patent and all supplementary exclusivity rights, as well as satisfying rigorous regulatory criteria for generic approval.

Impact on the Pharmaceutical Market

Effect on Drug Prices and Accessibility

The expiration of a drug patent is a pivotal market event with significant repercussions for drug prices, accessibility, and, ultimately, public health outcomes. When a patent expires, the exclusive market rights granted to the innovator end, and generic manufacturers can enter the market. This typically leads to a dramatic decrease in drug prices, sometimes resulting in reductions as significant as 40–70% within a few years.

Following patent expiration, price competition intensifies, and healthcare payers, including governments and insurers, benefit from the lower cost of treatment. The decreased prices are primarily due to competition among multiple generic entrants who must offer their products at significantly lower price points compared to the originator to gain market share. In some cases, the shift from brand-name to generic usage can result in price reductions up to 41% after four years, thereby translating into substantial cost savings for the healthcare system and improved patient adherence due to increased affordability.

Moreover, the increase in the number of generic competitors is often associated with a further downward trend in prices and enhanced market penetration. The dynamics of generic competition often result in the brand-name drug’s price falling even before the first generic is marketed, as the innovator may lower its price in anticipation of generic entry to maintain market share.

Ultimately, the availability of generic drugs following patent expiration significantly improves access to essential medicines, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where cost is a critical barrier to treatment. This influx of affordable alternatives not only fosters public health by ensuring broader distribution but also compels policymakers to continuously refine regulatory policies to balance innovation and access effectively.

Case Studies of Major Drugs Transitioning to Generic

Several case studies have illustrated the profound impact of patent expiration on the pharmaceutical market. For example, regulatory and legal strategies have often been employed to extend the market exclusivity of blockbuster drugs, thereby delaying generic entry. In one well-documented case, brand-name manufacturers used legal strategies such as listing multiple patents and initiating litigation to postpone generic market entry for several years, as observed in the litigation around the antidepressant Paxil.

Another scenario involves the phenomenon of authorized generics, where the brand-name manufacturer itself releases a generic version under the same brand name once the patent expires. This practice can sometimes mitigate the loss in revenue and complicate the competitive landscape, as the brand-name company may still capture a substantial share of the market despite the expiration of the initial patent.

In the United States, the Hatch-Waxman Act details a structured approach whereby the first generic applicant may receive 180 days of market exclusivity if successful in challenging the innovator’s patent. This period acts as both an incentive for generic manufacturers to initiate litigation and a mechanism to ensure that competition is eventually introduced into the market. Similar mechanisms are in place in other jurisdictions, although the specifics—such as the duration of exclusivity—vary depending on the country's regulatory framework.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that when generic entry occurs, the overall impact on drug prices is both significant and rapid, leading to enhanced market penetration and reduced costs for consumers. In the Netherlands, for example, a systematic review found that drug prices can decline by approximately 41% within four years after patent expiration, underscoring the critical role that generic competition plays in driving cost efficiencies and expanding treatment access.

Conclusion

In summary, a prescription drug patent typically lasts for 20 years from the date of filing, which is the standard legal duration worldwide. However, by the time the drug undergoes extensive research and clinical testing and receives regulatory approval, the effective period of market exclusivity available to the innovator is often reduced to approximately 10 to 12 years. Regulatory mechanisms such as patent term restoration or extension—allowing up to an additional 5 years in certain jurisdictions—and data exclusivity periods can further adjust this effective duration, prolonging the time before generics can enter the market.

Once the patent and all related exclusivity protections expire, generic manufacturers can enter the market by submitting an ANDA and proving bioequivalence to the originator drug. This process, governed by stringent regulatory frameworks to ensure safety and efficacy, opens the door for significant price reductions and enhanced drug accessibility, as evidenced by numerous case studies and market analyses across regions such as the United States, Europe, and Latin America.

From a broad perspective, the pharmaceutical patent system is designed to stimulate innovation by granting time-limited exclusivity, but it is equally structured to eventually benefit the public through the availability of more affordable generic alternatives. Detailed studies and references from reputable sources such as Synapse reveal that while the nominal patent duration is 20 years, the actual period during which a brand-name drug enjoys near-total market exclusivity is shorter—typically around a decade—after which generics can be made and marketed.

This system, when functioning as intended, helps balance the need for rewarding innovative drug development with the equally important goal of ensuring that life-saving and essential medicines remain accessible and affordable to patients globally. The interplay of patent duration, regulatory extensions, legal strategies like authorized generics, and the rigorous generic approval process collectively shape the dynamics of the pharmaceutical market, influencing both drug prices and patient access.

In conclusion, while the legal patent lasts 20 years, the practical timeframe for market exclusivity is often closer to 10–12 years post-approval, after which generic manufacturers are permitted to produce lower-cost alternatives following carefully regulated processes that ensure therapeutic equivalence and safety. This balanced approach, informed by robust regulatory frameworks, legal provisions, and market dynamics, ultimately serves the dual purpose of fostering pharmaceutical innovation and promoting public health by making drugs more affordable once their patents expire.

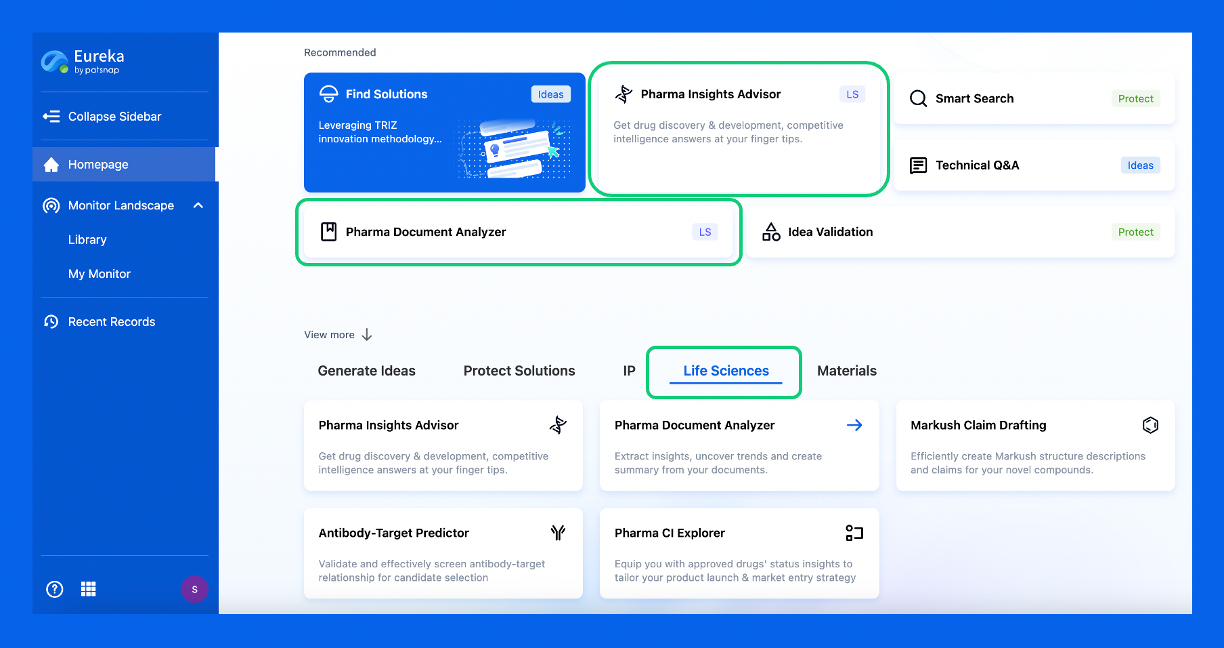

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.