Request Demo

How many FDA approved Probiotics are there?

17 March 2025

Introduction to Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. Over decades of research and historical use in fermented foods, probiotics have garnered attention for their potential to restore and maintain a balanced gut microbiota, support immune function, improve nutrient absorption, and even impact metabolic and neurobehavioral health. Traditional probiotic products are predominantly marketed as dietary supplements or as components of functional foods. Despite the extensive scientific literature supporting some of their benefits, the regulatory approach to probiotics remains unique compared to conventional pharmaceutical agents.

Definition and Health Benefits

Probiotics are defined by authoritative bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as live microorganisms that provide health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. They are most commonly derived from genera such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, and others. These beneficial microbes are known to enhance gut barrier function, competitively exclude pathogens, modulate immune responses, and improve the bioavailability of key nutrients. For example, certain probiotic formulations have been studied for their ability to increase protein absorption or modulate energy metabolism, making them attractive for populations with increased nutritional demands such as the elderly, children, pregnant women, and athletes. Furthermore, probiotics are linked to benefits in gastrointestinal function, such as the treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and reduction of symptoms in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

Overview of Probiotic Market

The global probiotic market has experienced significant growth over recent years. According to data referenced by the International Probiotic Association, the market is driven by increased consumer demand for health-enhancing functional foods and dietary supplements. The market landscape is broad, with products ranging from yogurts and fermented beverages to capsules and powders. Despite robust commercial interest and considerable investment in microbiome research, the classification and regulatory oversight of probiotics remains complex. In many countries, probiotics are sold without the need for pre-market approval by regulatory agencies because they are categorized as food supplements rather than drugs. In the United States, for example, many probiotic products are marketed under the dietary supplements category, with manufacturers relying on voluntary notifications and Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status rather than full FDA approval as a drug.

FDA Approval Process

Understanding the FDA approval process for probiotics involves a clear distinction between products that are intended for nutritional support and those aimed at treating or preventing disease. The FDA’s regulatory framework imposes different requirements on food supplements versus drug products, which can sometimes be a source of confusion for probiotics.

Regulatory Framework for Probiotics

Under U.S. law, the FDA governs products based on their intended use. Probiotic products marketed as dietary supplements or food ingredients do not require pre-market approval; instead, they must comply with standards such as Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and appropriate labeling requirements. Manufacturers of dietary supplements are responsible for ensuring that their products are safe and that any claims made about their benefits are substantiated by scientific evidence. In contrast, if a probiotic product is intended to be used as a drug (i.e., for the treatment, cure, or prevention of disease), it must go through the Investigational New Drug (IND) process and subsequent approval procedures that require extensive clinical data on safety and efficacy.

The regulatory framework for “live biotherapeutic products” (LBPs) is evolving. Although some products containing live microorganisms have been developed with an eye towards treatment of specific diseases, the FDA’s view of these as drugs means that clinical trials are strictly regulated. Notably, while probiotics as dietary supplements enjoy an exemption from pre-market approval, their designation as “drug” products has far-reaching implications regarding the scale of evidence required and the monitoring of potential adverse events.

Criteria for Approval

For a probiotic product to be approved by the FDA as a drug, several stringent criteria must be met:

- Safety and Tolerability: There must be robust evidence from preclinical and clinical trials demonstrating that the product is safe for human consumption and does not induce adverse events, particularly in vulnerable populations such as preterm infants.

- Efficacy: Clinical trials must be designed with rigorous endpoints and should show statistically significant benefits over placebo or standard treatments. The efficacy data must be reproducible and based on well-defined endpoints.

- Manufacturing and Quality Control: The manufacturing processes must adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). The product must contain live microorganisms at the levels stated on the label throughout its shelf life, with thorough documentation of the identity, purity, and potency of the strains used.

- Regulatory Status and Labeling: For dietary supplement products, a GRAS status or pre-October-1994 listing may apply, but for drug applications, the full dossier of clinical data is required.

These criteria ensure that only products with a clear benefit-risk balance are approved as therapeutic agents. However, because many probiotic products are marketed as supplements rather than drugs, they do not undergo this rigorous approval process.

Current Status of FDA Approved Probiotics

When addressing the question of how many FDA approved probiotics exist, it is essential to clarify the scope of the inquiry. The term “FDA approved probiotics” can be interpreted in different ways depending on the regulatory classification of the product.

List of Approved Probiotics

Based on the information from the available references, the FDA has not approved any probiotic products as drugs intended for the treatment or prevention of disease in the traditional sense. For example, a news article explains that “the FDA has not approved any probiotic product for use as a drug or biological product in infants of any age.” This statement reflects the reality that although there are many probiotic products on the market, they are not subject to the pre-market approval process required for drugs.

However, it is important to note that there have been FDA approvals for microbiota-based therapies that might share certain characteristics with probiotics. For instance, Ferring Pharmaceuticals’ REBYOTA™ and Seres/Nestlé Health Science’s VOWST™ have been approved by the FDA for use in treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI). These approvals represent the first instances of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) being granted FDA approval. Nevertheless, these products are not marketed as conventional probiotics; rather, they are considered pharmaceutical products designed to modulate the gut microbiota for a specific clinical indication. They are developed under a regulatory pathway that is distinct from that of dietary supplements.

In summary, if one strictly defines “FDA approved probiotics” as probiotic products that have received full FDA approval as drugs, the answer is that there are currently zero such products. All commercially available probiotics in the U.S. are sold as dietary supplements or food ingredients that do not require FDA pre-market approval.

Categories and Uses

Probiotic products in the United States fall into several broad categories based on their intended use and regulatory pathway:

1. Dietary Supplements and Functional Foods:

- These products are widely available in the form of capsules, yogurts, fermented beverages, and powders. They are marketed with general structure/function claims rather than specific health claims that require FDA approval.

- The manufacturers are responsible for ensuring that the probiotics meet quality standards such as viability and purity throughout the product’s shelf life. No pre-market approval is necessary under current regulations, although safety remains a shared responsibility between the FDA and the manufacturers.

2. Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs):

- This category includes products developed with the intention of treating or preventing diseases. LBPs undergo the rigorous clinical trial process required for drug products.

- Currently, the FDA has approved microbial-based therapies such as REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ specifically for treating recurrent CDI. These approvals, however, do not imply that traditional probiotic supplements are FDA approved as drugs.

3. Investigational New Drug (IND) Products:

- Some probiotic formulations intended for therapeutic use fall under investigational protocols. In these cases, clinical trials are conducted under IND oversight to determine safety and efficacy, but until the data are sufficient for submission of a Biologics License Application (BLA), the products are not fully approved.

Thus, while there is robust commercial availability of probiotic products, when it comes to FDA drug approval, the answer is that no probiotic product – if defined as a dietary supplement – has undergone the full FDA approval process as a drug. Only specific LBPs have achieved approval for narrow clinical indications.

Challenges and Considerations

The regulatory environment for probiotics is complex, and several challenges complicate the process of achieving FDA approval for any probiotic product when it is intended for use as a therapeutic agent. These challenges include the evolving science of the microbiome, variations in manufacturing practices, and differing interpretations of how probiotics should be classified.

Regulatory Challenges

1. Dichotomy Between Dietary Supplements and Drugs:

- The FDA classifies most probiotics as dietary supplements rather than pharmaceutical drugs. Dietary supplements do not require the same level of pre-market review or clinical evidence as drugs. This regulatory gap means that although there are many probiotic products on the market, none have been approved as drug products because they have not been subjected to that intensive scrutiny.

2. Strain-Specific Effects and Quality Control:

- The health benefits of probiotics are strain specific, and many products on the market have been criticized for inconsistencies between the label and the actual content, such as variations in the number or viability of probiotic strains.

- This variability can complicate efforts to conduct multi-center clinical trials and gather consistent efficacy data, which is essential for FDA drug approval.

3. Evolving Definition of Probiotics:

- With emerging research demonstrating that even non-viable bacteria or bacterial components (often referred to as postbiotics) may have beneficial effects, the traditional definition of a probiotic is evolving.

- This evolution in scientific understanding may eventually lead to adjustments in regulatory guidelines. Currently, the lack of a uniform standard for what constitutes an “approved” probiotic remains a challenge, and it contributes to the absence of any FDA-approved probiotic drugs.

4. Clinical Evidence and Study Design:

- Many clinical trials investigating probiotics have encountered issues such as small sample sizes, lack of standardized dosing, and methodological heterogeneity.

- The absence of large-scale, well-controlled clinical trials that meet FDA standards for efficacy and safety is one of the major reasons why no probiotic has yet received FDA approval as a drug.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, several factors hold promise for the integration of probiotic-based therapies into the regulatory framework for drug approval:

1. Advances in Microbiome Science:

- As our understanding of the human microbiota deepens, researchers are better able to identify which strains are most beneficial and elucidate their mechanisms of action.

- This enhanced understanding may lead to the development of targeted probiotics with clearly defined clinical benefits and safety profiles, facilitating their eventual approval as drug products.

2. Standardization and Quality Control:

- Improvements in manufacturing processes and analytical techniques are being made to ensure that probiotic products maintain consistent quality, purity, and potency.

- The adoption of rigorous standards for strain identification and viability testing may eventually bridge the gap between dietary supplements and approved therapeutic drugs.

3. Regulatory Pathway for Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs):

- The recent approvals of REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ represent an important step towards establishing a regulatory pathway for microbiota-based therapies.

- While these products do not fall under the traditional definition of probiotics sold as dietary supplements, their approval demonstrates that products based on live microorganisms can meet the FDA’s rigorous requirements when developed as drugs. This may encourage companies to invest in similar research for other indications.

4. Personalized Probiotic Therapies:

- With advances in genomics and personalized medicine, future probiotic therapies might be tailored based on an individual’s unique microbiome profile.

- Such personalized approaches could improve efficacy and minimize risks, thereby providing stronger clinical evidence that might support FDA approval in the future.

5. Interdisciplinary Collaboration:

- Greater collaboration between academic researchers, clinicians, and industry stakeholders is needed to design robust clinical trials and address the current gaps in evidence.

- Regulatory agencies such as the FDA are increasingly engaging with the scientific community to refine guidelines for novel microbial therapies, suggesting that further progress in this area is likely.

Conclusion

In conclusion, when asked “How many FDA approved Probiotics are there?”, the answer is nuanced and rests largely on the classification of these products. If we define probiotics in the context of dietary supplements or functional foods marketed for general health support, there are no FDA-approved probiotic drugs detailed as such because these products are not subject to the FDA approval process required for pharmaceutical agents. The vast majority of probiotic products available in the market are sold as dietary supplements and rely on GRAS status rather than formal FDA approval for safety and efficacy as a therapeutic intervention.

On the other hand, there has been progress in the area of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), with FDA approvals for products like REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ for the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections. These approvals, however, represent a very narrow subset of the broad field of probiotic and microbiome-based therapies and should not be confused with the commercial probiotic supplements widely available. Thus, for the traditional category of probiotics—which are typically intended for nutritional support and general health promotion—the FDA has effectively approved zero products as drugs.

This situation reflects broader regulatory challenges, including differing definitions of what constitutes a probiotic, variability in product quality, and the absence of standardized protocols for clinical validation. Despite these challenges, advances in microbiome science, manufacturing standardization, and evolving regulatory frameworks for LBPs hint at a future where therapeutic probiotics may receive formal FDA approval for specific health indications. A concerted effort in developing robust clinical trials, ensuring rigorous quality control, and establishing clear regulatory pathways will be crucial for achieving this goal.

Overall, while the FDA-approved landscape for probiotic-based drugs remains empty, the field is evolving rapidly. In the meantime, probiotics remain a popular and important component of the dietary supplement market, contributing significantly to public health through mechanisms that have been documented in both preclinical and clinical studies. A better understanding of regulatory pathways and heightened standards for product quality and clinical evidence may ultimately pave the way for future FDA approvals within the realm of probiotic therapies.

By summarizing the multiple perspectives from regulatory, clinical, and market standpoints, it is clear that there are currently no FDA-approved probiotics if one adheres to the strict definition of “approved as a drug.” However, the early signs from microbiota-based therapies such as REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ indicate that with further research, improved clinical data, and clearer regulatory guidelines, the future could see the first wave of truly FDA-approved probiotic therapies. Such developments would mark a significant milestone in the translation of probiotic and microbiome science into mainstream clinical practice.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. Over decades of research and historical use in fermented foods, probiotics have garnered attention for their potential to restore and maintain a balanced gut microbiota, support immune function, improve nutrient absorption, and even impact metabolic and neurobehavioral health. Traditional probiotic products are predominantly marketed as dietary supplements or as components of functional foods. Despite the extensive scientific literature supporting some of their benefits, the regulatory approach to probiotics remains unique compared to conventional pharmaceutical agents.

Definition and Health Benefits

Probiotics are defined by authoritative bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as live microorganisms that provide health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. They are most commonly derived from genera such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, and others. These beneficial microbes are known to enhance gut barrier function, competitively exclude pathogens, modulate immune responses, and improve the bioavailability of key nutrients. For example, certain probiotic formulations have been studied for their ability to increase protein absorption or modulate energy metabolism, making them attractive for populations with increased nutritional demands such as the elderly, children, pregnant women, and athletes. Furthermore, probiotics are linked to benefits in gastrointestinal function, such as the treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and reduction of symptoms in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

Overview of Probiotic Market

The global probiotic market has experienced significant growth over recent years. According to data referenced by the International Probiotic Association, the market is driven by increased consumer demand for health-enhancing functional foods and dietary supplements. The market landscape is broad, with products ranging from yogurts and fermented beverages to capsules and powders. Despite robust commercial interest and considerable investment in microbiome research, the classification and regulatory oversight of probiotics remains complex. In many countries, probiotics are sold without the need for pre-market approval by regulatory agencies because they are categorized as food supplements rather than drugs. In the United States, for example, many probiotic products are marketed under the dietary supplements category, with manufacturers relying on voluntary notifications and Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status rather than full FDA approval as a drug.

FDA Approval Process

Understanding the FDA approval process for probiotics involves a clear distinction between products that are intended for nutritional support and those aimed at treating or preventing disease. The FDA’s regulatory framework imposes different requirements on food supplements versus drug products, which can sometimes be a source of confusion for probiotics.

Regulatory Framework for Probiotics

Under U.S. law, the FDA governs products based on their intended use. Probiotic products marketed as dietary supplements or food ingredients do not require pre-market approval; instead, they must comply with standards such as Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and appropriate labeling requirements. Manufacturers of dietary supplements are responsible for ensuring that their products are safe and that any claims made about their benefits are substantiated by scientific evidence. In contrast, if a probiotic product is intended to be used as a drug (i.e., for the treatment, cure, or prevention of disease), it must go through the Investigational New Drug (IND) process and subsequent approval procedures that require extensive clinical data on safety and efficacy.

The regulatory framework for “live biotherapeutic products” (LBPs) is evolving. Although some products containing live microorganisms have been developed with an eye towards treatment of specific diseases, the FDA’s view of these as drugs means that clinical trials are strictly regulated. Notably, while probiotics as dietary supplements enjoy an exemption from pre-market approval, their designation as “drug” products has far-reaching implications regarding the scale of evidence required and the monitoring of potential adverse events.

Criteria for Approval

For a probiotic product to be approved by the FDA as a drug, several stringent criteria must be met:

- Safety and Tolerability: There must be robust evidence from preclinical and clinical trials demonstrating that the product is safe for human consumption and does not induce adverse events, particularly in vulnerable populations such as preterm infants.

- Efficacy: Clinical trials must be designed with rigorous endpoints and should show statistically significant benefits over placebo or standard treatments. The efficacy data must be reproducible and based on well-defined endpoints.

- Manufacturing and Quality Control: The manufacturing processes must adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). The product must contain live microorganisms at the levels stated on the label throughout its shelf life, with thorough documentation of the identity, purity, and potency of the strains used.

- Regulatory Status and Labeling: For dietary supplement products, a GRAS status or pre-October-1994 listing may apply, but for drug applications, the full dossier of clinical data is required.

These criteria ensure that only products with a clear benefit-risk balance are approved as therapeutic agents. However, because many probiotic products are marketed as supplements rather than drugs, they do not undergo this rigorous approval process.

Current Status of FDA Approved Probiotics

When addressing the question of how many FDA approved probiotics exist, it is essential to clarify the scope of the inquiry. The term “FDA approved probiotics” can be interpreted in different ways depending on the regulatory classification of the product.

List of Approved Probiotics

Based on the information from the available references, the FDA has not approved any probiotic products as drugs intended for the treatment or prevention of disease in the traditional sense. For example, a news article explains that “the FDA has not approved any probiotic product for use as a drug or biological product in infants of any age.” This statement reflects the reality that although there are many probiotic products on the market, they are not subject to the pre-market approval process required for drugs.

However, it is important to note that there have been FDA approvals for microbiota-based therapies that might share certain characteristics with probiotics. For instance, Ferring Pharmaceuticals’ REBYOTA™ and Seres/Nestlé Health Science’s VOWST™ have been approved by the FDA for use in treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI). These approvals represent the first instances of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) being granted FDA approval. Nevertheless, these products are not marketed as conventional probiotics; rather, they are considered pharmaceutical products designed to modulate the gut microbiota for a specific clinical indication. They are developed under a regulatory pathway that is distinct from that of dietary supplements.

In summary, if one strictly defines “FDA approved probiotics” as probiotic products that have received full FDA approval as drugs, the answer is that there are currently zero such products. All commercially available probiotics in the U.S. are sold as dietary supplements or food ingredients that do not require FDA pre-market approval.

Categories and Uses

Probiotic products in the United States fall into several broad categories based on their intended use and regulatory pathway:

1. Dietary Supplements and Functional Foods:

- These products are widely available in the form of capsules, yogurts, fermented beverages, and powders. They are marketed with general structure/function claims rather than specific health claims that require FDA approval.

- The manufacturers are responsible for ensuring that the probiotics meet quality standards such as viability and purity throughout the product’s shelf life. No pre-market approval is necessary under current regulations, although safety remains a shared responsibility between the FDA and the manufacturers.

2. Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs):

- This category includes products developed with the intention of treating or preventing diseases. LBPs undergo the rigorous clinical trial process required for drug products.

- Currently, the FDA has approved microbial-based therapies such as REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ specifically for treating recurrent CDI. These approvals, however, do not imply that traditional probiotic supplements are FDA approved as drugs.

3. Investigational New Drug (IND) Products:

- Some probiotic formulations intended for therapeutic use fall under investigational protocols. In these cases, clinical trials are conducted under IND oversight to determine safety and efficacy, but until the data are sufficient for submission of a Biologics License Application (BLA), the products are not fully approved.

Thus, while there is robust commercial availability of probiotic products, when it comes to FDA drug approval, the answer is that no probiotic product – if defined as a dietary supplement – has undergone the full FDA approval process as a drug. Only specific LBPs have achieved approval for narrow clinical indications.

Challenges and Considerations

The regulatory environment for probiotics is complex, and several challenges complicate the process of achieving FDA approval for any probiotic product when it is intended for use as a therapeutic agent. These challenges include the evolving science of the microbiome, variations in manufacturing practices, and differing interpretations of how probiotics should be classified.

Regulatory Challenges

1. Dichotomy Between Dietary Supplements and Drugs:

- The FDA classifies most probiotics as dietary supplements rather than pharmaceutical drugs. Dietary supplements do not require the same level of pre-market review or clinical evidence as drugs. This regulatory gap means that although there are many probiotic products on the market, none have been approved as drug products because they have not been subjected to that intensive scrutiny.

2. Strain-Specific Effects and Quality Control:

- The health benefits of probiotics are strain specific, and many products on the market have been criticized for inconsistencies between the label and the actual content, such as variations in the number or viability of probiotic strains.

- This variability can complicate efforts to conduct multi-center clinical trials and gather consistent efficacy data, which is essential for FDA drug approval.

3. Evolving Definition of Probiotics:

- With emerging research demonstrating that even non-viable bacteria or bacterial components (often referred to as postbiotics) may have beneficial effects, the traditional definition of a probiotic is evolving.

- This evolution in scientific understanding may eventually lead to adjustments in regulatory guidelines. Currently, the lack of a uniform standard for what constitutes an “approved” probiotic remains a challenge, and it contributes to the absence of any FDA-approved probiotic drugs.

4. Clinical Evidence and Study Design:

- Many clinical trials investigating probiotics have encountered issues such as small sample sizes, lack of standardized dosing, and methodological heterogeneity.

- The absence of large-scale, well-controlled clinical trials that meet FDA standards for efficacy and safety is one of the major reasons why no probiotic has yet received FDA approval as a drug.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, several factors hold promise for the integration of probiotic-based therapies into the regulatory framework for drug approval:

1. Advances in Microbiome Science:

- As our understanding of the human microbiota deepens, researchers are better able to identify which strains are most beneficial and elucidate their mechanisms of action.

- This enhanced understanding may lead to the development of targeted probiotics with clearly defined clinical benefits and safety profiles, facilitating their eventual approval as drug products.

2. Standardization and Quality Control:

- Improvements in manufacturing processes and analytical techniques are being made to ensure that probiotic products maintain consistent quality, purity, and potency.

- The adoption of rigorous standards for strain identification and viability testing may eventually bridge the gap between dietary supplements and approved therapeutic drugs.

3. Regulatory Pathway for Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs):

- The recent approvals of REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ represent an important step towards establishing a regulatory pathway for microbiota-based therapies.

- While these products do not fall under the traditional definition of probiotics sold as dietary supplements, their approval demonstrates that products based on live microorganisms can meet the FDA’s rigorous requirements when developed as drugs. This may encourage companies to invest in similar research for other indications.

4. Personalized Probiotic Therapies:

- With advances in genomics and personalized medicine, future probiotic therapies might be tailored based on an individual’s unique microbiome profile.

- Such personalized approaches could improve efficacy and minimize risks, thereby providing stronger clinical evidence that might support FDA approval in the future.

5. Interdisciplinary Collaboration:

- Greater collaboration between academic researchers, clinicians, and industry stakeholders is needed to design robust clinical trials and address the current gaps in evidence.

- Regulatory agencies such as the FDA are increasingly engaging with the scientific community to refine guidelines for novel microbial therapies, suggesting that further progress in this area is likely.

Conclusion

In conclusion, when asked “How many FDA approved Probiotics are there?”, the answer is nuanced and rests largely on the classification of these products. If we define probiotics in the context of dietary supplements or functional foods marketed for general health support, there are no FDA-approved probiotic drugs detailed as such because these products are not subject to the FDA approval process required for pharmaceutical agents. The vast majority of probiotic products available in the market are sold as dietary supplements and rely on GRAS status rather than formal FDA approval for safety and efficacy as a therapeutic intervention.

On the other hand, there has been progress in the area of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), with FDA approvals for products like REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ for the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections. These approvals, however, represent a very narrow subset of the broad field of probiotic and microbiome-based therapies and should not be confused with the commercial probiotic supplements widely available. Thus, for the traditional category of probiotics—which are typically intended for nutritional support and general health promotion—the FDA has effectively approved zero products as drugs.

This situation reflects broader regulatory challenges, including differing definitions of what constitutes a probiotic, variability in product quality, and the absence of standardized protocols for clinical validation. Despite these challenges, advances in microbiome science, manufacturing standardization, and evolving regulatory frameworks for LBPs hint at a future where therapeutic probiotics may receive formal FDA approval for specific health indications. A concerted effort in developing robust clinical trials, ensuring rigorous quality control, and establishing clear regulatory pathways will be crucial for achieving this goal.

Overall, while the FDA-approved landscape for probiotic-based drugs remains empty, the field is evolving rapidly. In the meantime, probiotics remain a popular and important component of the dietary supplement market, contributing significantly to public health through mechanisms that have been documented in both preclinical and clinical studies. A better understanding of regulatory pathways and heightened standards for product quality and clinical evidence may ultimately pave the way for future FDA approvals within the realm of probiotic therapies.

By summarizing the multiple perspectives from regulatory, clinical, and market standpoints, it is clear that there are currently no FDA-approved probiotics if one adheres to the strict definition of “approved as a drug.” However, the early signs from microbiota-based therapies such as REBYOTA™ and VOWST™ indicate that with further research, improved clinical data, and clearer regulatory guidelines, the future could see the first wave of truly FDA-approved probiotic therapies. Such developments would mark a significant milestone in the translation of probiotic and microbiome science into mainstream clinical practice.

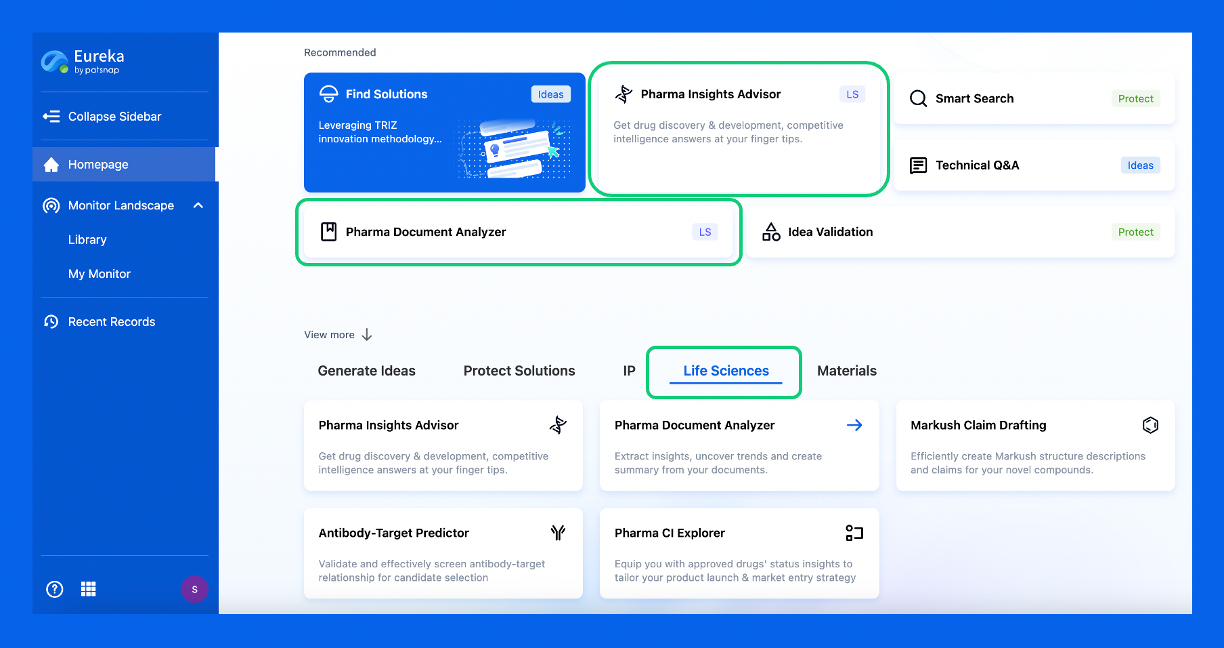

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.