Request Demo

What are the criteria for a drug to be considered “first-in-class”?

21 March 2025

Understanding 'First-in-Class' Drugs

Definition and Importance

A “first‐in‐class” drug is broadly defined as a therapeutic agent that introduces a completely novel mechanism of action into clinical practice. Unlike drugs that simply fine‐tune dosage or improve upon an existing molecular structure (sometimes labeled as “follow‐on” or “best‐in‐class”), first‐in‐class compounds are the first to target a particular molecular pathway or receptor in a specific disease context. Their importance lies in their capacity to expand the treatment arsenal, especially for conditions that have not been effectively treated using previous pharmacological methods. Moreover, first‐in‐class drugs often represent breakthroughs that can change the landscape of treatment paradigms, offering an entirely new approach to managing diseases while sometimes addressing previously unmet medical needs. From a health–policy perspective, first‐in‐class drugs are closely scrutinized by regulatory agencies and payers because they typically come with higher uncertainties but also potential dramatic therapeutic improvements. They serve as beacons for future innovation, not only invigorating the clinical community with new insights into disease mechanisms but also inciting competitive improvements and market re–structuring in the pharmaceutical industry.

Comparison with 'Best-in-Class'

While the term “first‐in‐class” highlights novelty and pioneering mechanism of action, “best‐in‐class” drugs emphasize clinical superiority in efficacy, safety, or convenience compared with earlier entrants in the same therapeutic category. In many cases, a best‐in‐class drug may have been introduced later than the first‐in‐class but offers incremental improvements such as enhanced tolerability, improved pharmacokinetics or dosing convenience. Interestingly, studies have observed that the market entry order is not always predictive of therapeutic superiority; indeed, while first‐in‐class drugs often open new treatment avenues, best‐in‐class drugs can sometimes overshadow them later by delivering clear clinical benefits and minimized side effects. Thus, the distinction is significant from both a scientific and commercial perspective since developers must weigh the risk–benefit profile of pioneering a drug with a novel mechanism versus of improving on an already approved mechanism.

Criteria for 'First-in-Class' Designation

When considering the specific criteria that define a drug as first‐in‐class, multiple factors merge—from its underlying biology to regulatory acceptance. The criteria span three key domains: the novelty of the mechanism of action, the degree to which it meets an unmet medical need, and the regulatory considerations that support a distinct classification.

Novel Mechanism of Action

The foremost criterion for a drug to be deemed first‐in‐class is that it relies on a novel mechanism of action that has never been exploited before or that dramatically differs from existing therapeutic modalities.

- Unique Biological Target: A first‐in‐class drug acts through a molecular target or pathway that is not addressed by any other marketed drug at the time of review. For example, if a candidate molecule engages a receptor that was previously considered “undruggable” or completely unexploited, it would be categorized as first‐in‐class. The novelty is determined by comparing the chemical structure, receptor binding, and downstream signal transduction activities with approved therapeutic modalities.

- Innovative Mode–of–Action: Research and regulatory literature emphasize that a novel mechanism should not simply be a chemical tweak of an existing compound but must bring an entirely new pharmacological strategy to bear. This may include unique receptor modulation, novel enzyme inhibition, or activation of entirely new intracellular cascades that open avenues for treating disease. In practicable terms, the manufacturer has to demonstrate a previously unrecognized mode–of–action, supported by preclinical studies, and then further validated in early clinical proof–of–concept studies.

- Scientific and Translational Evidence: The evidence for novelty may stem from advances in molecular biology, high–throughput screening, and emerging computational techniques such as machine–learning–driven de novo drug design. These innovative approaches have increased the search span of chemical space and enabled the identification of compounds with unparalleled mechanisms of action. Every first‐in‐class designation relies on a robust series of mechanistic studies showing that the therapeutic effect is mediated by novel target engagement rather than by mere off–target effects or non–specific binding processes.

Unmet Medical Needs

A critical component of the first‐in‐class designation is the demonstration of a significant gap in therapy:

- Addressing Unmet Medical Need: First‐in‐class drugs often target conditions where there are no adequate therapeutic options. In many therapeutic areas – such as rare diseases, oncology, or chronic progressive conditions – the introduction of a drug with a unique mechanism provides a breakthrough for patients who previously had limited options. Regulatory documents underscore that when a drug is being developed to meet an unmet medical need, its innovative mechanism becomes even more crucial, as it can lead to orphan drug status or breakthrough designation.

- Orphan Drug Considerations: A notable overlap exists between first‐in‐class drugs and orphan drugs; more than 50% of first‐in‐class therapies are frequently developed to cater to rare diseases where conventional therapies are missing. This alignment emphasizes the need to meet severe, often life–threatening conditions that conventional treatment paradigms have not successfully addressed.

- Clinical Impact and Therapeutic Advantage: Beyond simply filling a gap, first‐in‐class drugs are expected to provide a therapeutic advantage over previous treatments. This may be seen in improved efficacy, better safety profiles, or even improved patient compliance owing to novel delivery systems and dosages. By offering a change in the risk–benefit ratio, these drugs change clinical practice and provide additional value that justifies their designation as first–in–class.

Regulatory Considerations

Regulatory bodies such as the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada place significant weight on the novelty and innovative character of a drug:

- Regulatory Evaluation of Novelty: In the context of regulatory submissions, a drug is labeled “first‐in‐class” if it is clearly identified as a compound with a new therapeutic mechanism that distinguishes it from previously approved drugs for the same indication. The FDA’s annual Novel Drug Summary and similar documents from regulatory bodies play a key role in this classification.

- Breakthrough Therapy and Priority Review Designations: Programs such as Breakthrough Therapy and Fast Track designations are often awarded to first‐in‐class drugs, recognizing their potential to deliver substantial improvements over existing treatments. These designations are granted when preliminary evidence indicates that the new product may demonstrate significant clinical benefits on one or more endpoints.

- Harmonizing Standards and Guidelines: Despite diverse regulatory environments, leading agencies coordinate on principles that equate novelty with first–in–class status. This includes accepting innovative clinical trial designs, conditional approvals when early promise is shown in pivotal endpoints, and in some cases providing incentives such as expedited review procedures. Regulatory considerations not only help in designating the drug but also set the stage for obligatory post–marketing surveillance aimed at confirming its safety and long–term efficacy.

Development and Approval Process

Even once a first‐in‐class candidate is identified, its pathway through drug development and regulatory approval is rigorous and multifaceted, and understanding these stages is critical to its eventual designation.

Research and Development Stages

The journey toward a first‐in‐class designation begins long before the drug enters clinical trials:

- Discovery and Preclinical Research: Drug discovery involves the identification and optimization of a hit molecule that interacts with a novel target. Researchers use computational methods, high–throughput screening assays, and structure–based design techniques to design molecules that possess the desired innovative mechanism. Preclinical studies, conducted in cell cultures and animal models, provide data on pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and initial toxicity. For first–in‐class drugs, preclinical research must convincingly demonstrate that the novel mechanism translates to the desired physiological effect.

- Translational Science Integration: Transitioning from discovery to clinical evaluation entails a detailed preclinical dossier that supports the mechanistic promise observed. Here, integration of data from enzymatic studies, receptor binding assays, and even emerging biomarker–driven translational studies is crucial. For instance, advanced imaging techniques and system pharmacology approaches help verify drug–target interactions in relevant disease models, ensuring that the new mechanism indeed holds potential in a clinical scenario.

- Optimization for Therapeutic Efficacy: There is also significant emphasis on optimizing dose, improving chemical stability, and ensuring that the drug candidate exhibits optimal bioavailability. The formulation science (or preformulation studies) is vital as it addresses solubility, absorption, and the eventual delivery mechanism, all of which are important for first‐in‐class compounds that may pursue innovative routes of administration.

Clinical Trial Phases

The clinical trial process for first‐in‐class drugs follows a series of rigorous phases, each aimed at confirming safety and efficacy:

- Phase 1 – Early Safety and Mechanism–of Action Evaluation: In first–in–human (FIH) studies, the primary focus is on safety, dose–range finding, pharmacokinetic profiling, and in some cases, early signals of pharmacodynamic response. For first‐in‐class drugs, these studies also serve to provide early clinical proof–of–concept that the novel mechanism of action functions in human subjects. In oncology, for instance, it is imperative that early clinical trials do not solely focus on efficacy endpoints but also evaluate potential adverse drug reactions that may be unique to an untested mechanism.

- Phase 2 – Efficacy and Dose–Optimization: Subsequent trials aim to assess therapeutic efficacy in the target patient population. For a first‐in‐class drug, phase 2 studies are crucial to demonstrating that the innovative mechanism translates into measurable clinical benefits and improved patient outcomes. Detailed early clinical data, including biomarker analyses and patient‐stratification criteria, are integral because they help define subpopulations that may benefit most from the novel therapeutic approach.

- Phase 3 – Confirmatory Trials and Broader Indication Testing: Phase 3 trials involve large patient cohorts and are designed to confirm the drug’s effectiveness, monitor side effects, and compare it with standard or placebo treatments. For first‐in‐class drugs, these trials face extra scrutiny as they are the first representative of a new therapeutic mechanism; hence, they aim to solidify the drug's distinct clinical profile and to detail how safety benefits or adverse effects weigh against its novel attribute.

- Adaptive Trial Designs: Given the innovative nature of first‐in‐class drugs, adaptive clinical trial methodologies are increasingly employed. These allow adjustments to trial parameters such as dosage or patient selection based on interim results. This flexibility is particularly important when a novel mechanism’s risk–benefit ratio is still being elucidated.

Regulatory Approval Pathways

Regulatory agencies have progressively tailored their review processes to facilitate the approval of first‐in‐class drugs given their potential benefits and inherent risks:

- Expedited Review Procedures: Recognizing the clinical promise of a drug with a novel mechanism, agencies such as the FDA often offer expedited review options. For example, first‐in‐class drugs developing in areas of high unmet need may benefit from Breakthrough Therapy, Fast Track, or Priority Review designations that reduce the review time significantly—from standard periods to as short as six months in some cases.

- Conditional and Adaptive Approvals: In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) offers conditional approvals and the PRIME (PRIority Medicines) scheme for new drugs that exhibit significant promise but whose clinical data may be limited because of the urgent nature of unmet needs. This regulatory flexibility allows for patient access to innovative therapies even while additional data is being gathered post–approval.

- Post–Marketing Surveillance and Effectiveness Monitoring: Once approved, first‐in‐class drugs are subject to heightened post–marketing surveillance to confirm safety in broader populations over longer periods. This surveillance is particularly critical given the inherent uncertainties associated with a novel mode–of–action that may generate unexpected adverse reactions in real–world settings.

- Global Harmonization Efforts: Internationally, there is a growing emphasis on harmonizing the regulatory criteria that define first‐in‐class drugs across major markets such as the United States, European Union, and Canada. Such efforts aim to standardize the innovation criteria, facilitate mutual recognition of approval data, and streamline multi–regional clinical trial designs.

Impact and Case Studies

Successful 'First-in-Class' Drugs

There are multiple celebrated examples of drugs that have achieved first‐in‐class status and subsequently transformed therapeutic practice:

- Revolutionary Oncology Agents: Many first‐in‐class drugs, particularly in oncology, have offered new hope to patients with few alternatives. For instance, drugs such as the first–approved monoclonal antibodies or inhibitors targeting novel epigenetic regulators (e.g., EZH2 inhibitors) have redefined the treatment of certain sarcomas or hematologic malignancies by introducing a novel therapeutic pathway.

- Orphan Drug Approvals: A significant fraction of first–in–class drugs are also developed as orphan drugs. For example, innovative compounds like lonafarnib (a farnesyltransferase inhibitor) have gained approval to treat rare diseases by targeting previously untapped biological pathways. These groundbreaking therapies provide tangible examples of how first–in–class drugs serve critical niche areas where traditional therapies have failed to deliver substantial benefits.

- Comparative Evidence in Clinical Trials: Case–studies described in research often illustrate that first‐in‐class drugs achieve breakthrough status when early clinical data support a significant improvement over the standard-of-care. Often, the documentation of a new receptor or pathway being targeted is accompanied by detailed mechanistic studies, expansive biomarker–driven patient stratification, and adaptive trial protocols.

Market and Competitive Advantages

From a commercial viewpoint, first‐in‐class drugs have unique market characteristics:

- First–Mover Advantages: As the pioneers in their therapeutic area, first–in–class drugs often benefit from brand recognition and market exclusivity—at least for the period before competitors introduce follow–on products that may refine the drug’s profile. This early market presence can translate into sustained revenue, increased investment, and a strong influence on prescribing practices.

- Regulatory and Pricing Incentives: Owing to their innovative nature, first‐in‐class drugs often receive special regulatory designations that not only expedite their market entry but also confer extended exclusivity periods. These incentives are particularly appealing in therapeutic areas marked by high unmet needs. Additionally, if a first‐in‐class drug demonstrates clear clinical benefit, it may receive premium pricing and favorable reimbursement decisions which further consolidate its competitive advantage.

- Catalyst for Subsequent Innovation: The launch of a first‐in‐class drug often sets off a wave of follow–on innovation. Although many follow–on drugs are eventually classified as “me-too” or incremental improvements, the initial breakthrough can create a robust innovation ecosystem where multiple manufacturers subsequently compete, leading to overall improved treatment options for patients.

Challenges and Risks

Despite the immense potential, being designated as first‐in‐class is accompanied by significant challenges:

- High Attrition Rates in Clinical Development: Clinical trials for first–in–class drugs are inherently risky because the novel mechanism may harbor unforeseen side effects or have unpredictable efficacy outcomes. Historically, many first–in–class candidates fail in clinical stages due to issues related to toxicity, off-target effects, or simply suboptimal therapeutic effects.

- Regulatory Uncertainty: Although expedited pathways exist, regulators require robust evidence in the form of clinical and mechanistic data. This dual requirement often translates into longer development times and higher financial risk. Moreover, while breakthrough designations facilitate early market access, post–marketing surveillance may reveal adverse events that were not anticipated in clinical trials, thereby affecting the drug’s long-term safety profile.

- Market Competition Dynamics: The initial exclusivity enjoyed by first–in–class drugs can be eroded if competitors develop best‐in‐class drugs that offer improved efficacy or safety profiles. In such cases, the commercial advantage of the pioneer is challenged, and market share can shift quickly to those subsequent drugs, impacting the overall return on investment.

- Complexity of Development and Manufacturing: First–in‐class drugs, particularly those that target novel or “undruggable” proteins, often require innovative manufacturing processes, specialized formulation strategies, and rigorous quality–control measures. All these add layers of complexity and cost that must be managed by the sponsoring company.

Conclusion

In summary, to be considered “first‐in‐class,” a drug must fulfill several stringent criteria that cut across scientific innovation, clinical need, regulatory acceptance, and market dynamics. First–in–class drugs are defined primarily by their novel mechanism of action—a target or pathway that has not been exploited before—and by their potential to address a significant unmet medical need, often in disease areas where conventional therapies do not suffice. The evaluation of such drugs begins in the early days of drug discovery through robust preclinical testing and advanced computational modeling and continues as the drug moves through carefully designed clinical trial phases that include adaptive and innovative study designs. Regulatory considerations further cement this status through designations like Breakthrough Therapy, Fast Track, or Priority Review, allowing these products to access expedited review pathways while ensuring vigilance through rigorous post–marketing surveillance.

The impact of first‐in‐class drugs extends beyond clinical innovation; they re–shape market dynamics by establishing a precedent for follow–on competitors and forming a basis for future drug innovation. Successful case studies in oncology and rare diseases have demonstrated that first–in‐class therapies can provide dramatic improvements in patient management when compared to traditional treatments. However, the high attrition rates during clinical trials, significant development risks, and ongoing regulatory scrutiny present persistent challenges. The commercial environment is equally demanding as first–in‐class drugs must maintain their early–mover advantage even as “best‐in‐class” drugs eventually emerge to provide refined treatment options.

Ultimately, the designation of first‐in‐class is a multi–dimensional evaluation process—requiring a convergence of novel scientific discovery, fulfillment of an unmet medical void, and meeting rigorous regulatory standards. With an increased understanding of complex biological systems and the advent of innovative technologies in drug discovery, the landscape of first‐in‐class therapeutics is continuously evolving. This evolution promises improved patient outcomes and a dynamic shift toward more personalized and effective therapies while also demanding constant vigilance concerning safety and long–term efficacy. Moving forward, pharmaceutical innovators and regulatory bodies alike must balance the excitement of breakthrough therapies with the practical challenges inherent in developing and approving drugs that truly transform clinical practice.

In conclusion, a drug is considered “first‐in‐class” if it demonstrates a truly novel mechanism of action that is distinct from existing therapies, addresses a significant unmet medical need, and meets the stringent criteria set forth in clinical research and regulatory review. Success in this category not only opens new therapeutic horizons for patients but also fuels further innovation in drug development, despite the attendant risks and challenges associated with pioneering a new pharmacological landscape.

Definition and Importance

A “first‐in‐class” drug is broadly defined as a therapeutic agent that introduces a completely novel mechanism of action into clinical practice. Unlike drugs that simply fine‐tune dosage or improve upon an existing molecular structure (sometimes labeled as “follow‐on” or “best‐in‐class”), first‐in‐class compounds are the first to target a particular molecular pathway or receptor in a specific disease context. Their importance lies in their capacity to expand the treatment arsenal, especially for conditions that have not been effectively treated using previous pharmacological methods. Moreover, first‐in‐class drugs often represent breakthroughs that can change the landscape of treatment paradigms, offering an entirely new approach to managing diseases while sometimes addressing previously unmet medical needs. From a health–policy perspective, first‐in‐class drugs are closely scrutinized by regulatory agencies and payers because they typically come with higher uncertainties but also potential dramatic therapeutic improvements. They serve as beacons for future innovation, not only invigorating the clinical community with new insights into disease mechanisms but also inciting competitive improvements and market re–structuring in the pharmaceutical industry.

Comparison with 'Best-in-Class'

While the term “first‐in‐class” highlights novelty and pioneering mechanism of action, “best‐in‐class” drugs emphasize clinical superiority in efficacy, safety, or convenience compared with earlier entrants in the same therapeutic category. In many cases, a best‐in‐class drug may have been introduced later than the first‐in‐class but offers incremental improvements such as enhanced tolerability, improved pharmacokinetics or dosing convenience. Interestingly, studies have observed that the market entry order is not always predictive of therapeutic superiority; indeed, while first‐in‐class drugs often open new treatment avenues, best‐in‐class drugs can sometimes overshadow them later by delivering clear clinical benefits and minimized side effects. Thus, the distinction is significant from both a scientific and commercial perspective since developers must weigh the risk–benefit profile of pioneering a drug with a novel mechanism versus of improving on an already approved mechanism.

Criteria for 'First-in-Class' Designation

When considering the specific criteria that define a drug as first‐in‐class, multiple factors merge—from its underlying biology to regulatory acceptance. The criteria span three key domains: the novelty of the mechanism of action, the degree to which it meets an unmet medical need, and the regulatory considerations that support a distinct classification.

Novel Mechanism of Action

The foremost criterion for a drug to be deemed first‐in‐class is that it relies on a novel mechanism of action that has never been exploited before or that dramatically differs from existing therapeutic modalities.

- Unique Biological Target: A first‐in‐class drug acts through a molecular target or pathway that is not addressed by any other marketed drug at the time of review. For example, if a candidate molecule engages a receptor that was previously considered “undruggable” or completely unexploited, it would be categorized as first‐in‐class. The novelty is determined by comparing the chemical structure, receptor binding, and downstream signal transduction activities with approved therapeutic modalities.

- Innovative Mode–of–Action: Research and regulatory literature emphasize that a novel mechanism should not simply be a chemical tweak of an existing compound but must bring an entirely new pharmacological strategy to bear. This may include unique receptor modulation, novel enzyme inhibition, or activation of entirely new intracellular cascades that open avenues for treating disease. In practicable terms, the manufacturer has to demonstrate a previously unrecognized mode–of–action, supported by preclinical studies, and then further validated in early clinical proof–of–concept studies.

- Scientific and Translational Evidence: The evidence for novelty may stem from advances in molecular biology, high–throughput screening, and emerging computational techniques such as machine–learning–driven de novo drug design. These innovative approaches have increased the search span of chemical space and enabled the identification of compounds with unparalleled mechanisms of action. Every first‐in‐class designation relies on a robust series of mechanistic studies showing that the therapeutic effect is mediated by novel target engagement rather than by mere off–target effects or non–specific binding processes.

Unmet Medical Needs

A critical component of the first‐in‐class designation is the demonstration of a significant gap in therapy:

- Addressing Unmet Medical Need: First‐in‐class drugs often target conditions where there are no adequate therapeutic options. In many therapeutic areas – such as rare diseases, oncology, or chronic progressive conditions – the introduction of a drug with a unique mechanism provides a breakthrough for patients who previously had limited options. Regulatory documents underscore that when a drug is being developed to meet an unmet medical need, its innovative mechanism becomes even more crucial, as it can lead to orphan drug status or breakthrough designation.

- Orphan Drug Considerations: A notable overlap exists between first‐in‐class drugs and orphan drugs; more than 50% of first‐in‐class therapies are frequently developed to cater to rare diseases where conventional therapies are missing. This alignment emphasizes the need to meet severe, often life–threatening conditions that conventional treatment paradigms have not successfully addressed.

- Clinical Impact and Therapeutic Advantage: Beyond simply filling a gap, first‐in‐class drugs are expected to provide a therapeutic advantage over previous treatments. This may be seen in improved efficacy, better safety profiles, or even improved patient compliance owing to novel delivery systems and dosages. By offering a change in the risk–benefit ratio, these drugs change clinical practice and provide additional value that justifies their designation as first–in–class.

Regulatory Considerations

Regulatory bodies such as the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada place significant weight on the novelty and innovative character of a drug:

- Regulatory Evaluation of Novelty: In the context of regulatory submissions, a drug is labeled “first‐in‐class” if it is clearly identified as a compound with a new therapeutic mechanism that distinguishes it from previously approved drugs for the same indication. The FDA’s annual Novel Drug Summary and similar documents from regulatory bodies play a key role in this classification.

- Breakthrough Therapy and Priority Review Designations: Programs such as Breakthrough Therapy and Fast Track designations are often awarded to first‐in‐class drugs, recognizing their potential to deliver substantial improvements over existing treatments. These designations are granted when preliminary evidence indicates that the new product may demonstrate significant clinical benefits on one or more endpoints.

- Harmonizing Standards and Guidelines: Despite diverse regulatory environments, leading agencies coordinate on principles that equate novelty with first–in–class status. This includes accepting innovative clinical trial designs, conditional approvals when early promise is shown in pivotal endpoints, and in some cases providing incentives such as expedited review procedures. Regulatory considerations not only help in designating the drug but also set the stage for obligatory post–marketing surveillance aimed at confirming its safety and long–term efficacy.

Development and Approval Process

Even once a first‐in‐class candidate is identified, its pathway through drug development and regulatory approval is rigorous and multifaceted, and understanding these stages is critical to its eventual designation.

Research and Development Stages

The journey toward a first‐in‐class designation begins long before the drug enters clinical trials:

- Discovery and Preclinical Research: Drug discovery involves the identification and optimization of a hit molecule that interacts with a novel target. Researchers use computational methods, high–throughput screening assays, and structure–based design techniques to design molecules that possess the desired innovative mechanism. Preclinical studies, conducted in cell cultures and animal models, provide data on pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and initial toxicity. For first–in‐class drugs, preclinical research must convincingly demonstrate that the novel mechanism translates to the desired physiological effect.

- Translational Science Integration: Transitioning from discovery to clinical evaluation entails a detailed preclinical dossier that supports the mechanistic promise observed. Here, integration of data from enzymatic studies, receptor binding assays, and even emerging biomarker–driven translational studies is crucial. For instance, advanced imaging techniques and system pharmacology approaches help verify drug–target interactions in relevant disease models, ensuring that the new mechanism indeed holds potential in a clinical scenario.

- Optimization for Therapeutic Efficacy: There is also significant emphasis on optimizing dose, improving chemical stability, and ensuring that the drug candidate exhibits optimal bioavailability. The formulation science (or preformulation studies) is vital as it addresses solubility, absorption, and the eventual delivery mechanism, all of which are important for first‐in‐class compounds that may pursue innovative routes of administration.

Clinical Trial Phases

The clinical trial process for first‐in‐class drugs follows a series of rigorous phases, each aimed at confirming safety and efficacy:

- Phase 1 – Early Safety and Mechanism–of Action Evaluation: In first–in–human (FIH) studies, the primary focus is on safety, dose–range finding, pharmacokinetic profiling, and in some cases, early signals of pharmacodynamic response. For first‐in‐class drugs, these studies also serve to provide early clinical proof–of–concept that the novel mechanism of action functions in human subjects. In oncology, for instance, it is imperative that early clinical trials do not solely focus on efficacy endpoints but also evaluate potential adverse drug reactions that may be unique to an untested mechanism.

- Phase 2 – Efficacy and Dose–Optimization: Subsequent trials aim to assess therapeutic efficacy in the target patient population. For a first‐in‐class drug, phase 2 studies are crucial to demonstrating that the innovative mechanism translates into measurable clinical benefits and improved patient outcomes. Detailed early clinical data, including biomarker analyses and patient‐stratification criteria, are integral because they help define subpopulations that may benefit most from the novel therapeutic approach.

- Phase 3 – Confirmatory Trials and Broader Indication Testing: Phase 3 trials involve large patient cohorts and are designed to confirm the drug’s effectiveness, monitor side effects, and compare it with standard or placebo treatments. For first‐in‐class drugs, these trials face extra scrutiny as they are the first representative of a new therapeutic mechanism; hence, they aim to solidify the drug's distinct clinical profile and to detail how safety benefits or adverse effects weigh against its novel attribute.

- Adaptive Trial Designs: Given the innovative nature of first‐in‐class drugs, adaptive clinical trial methodologies are increasingly employed. These allow adjustments to trial parameters such as dosage or patient selection based on interim results. This flexibility is particularly important when a novel mechanism’s risk–benefit ratio is still being elucidated.

Regulatory Approval Pathways

Regulatory agencies have progressively tailored their review processes to facilitate the approval of first‐in‐class drugs given their potential benefits and inherent risks:

- Expedited Review Procedures: Recognizing the clinical promise of a drug with a novel mechanism, agencies such as the FDA often offer expedited review options. For example, first‐in‐class drugs developing in areas of high unmet need may benefit from Breakthrough Therapy, Fast Track, or Priority Review designations that reduce the review time significantly—from standard periods to as short as six months in some cases.

- Conditional and Adaptive Approvals: In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) offers conditional approvals and the PRIME (PRIority Medicines) scheme for new drugs that exhibit significant promise but whose clinical data may be limited because of the urgent nature of unmet needs. This regulatory flexibility allows for patient access to innovative therapies even while additional data is being gathered post–approval.

- Post–Marketing Surveillance and Effectiveness Monitoring: Once approved, first‐in‐class drugs are subject to heightened post–marketing surveillance to confirm safety in broader populations over longer periods. This surveillance is particularly critical given the inherent uncertainties associated with a novel mode–of–action that may generate unexpected adverse reactions in real–world settings.

- Global Harmonization Efforts: Internationally, there is a growing emphasis on harmonizing the regulatory criteria that define first‐in‐class drugs across major markets such as the United States, European Union, and Canada. Such efforts aim to standardize the innovation criteria, facilitate mutual recognition of approval data, and streamline multi–regional clinical trial designs.

Impact and Case Studies

Successful 'First-in-Class' Drugs

There are multiple celebrated examples of drugs that have achieved first‐in‐class status and subsequently transformed therapeutic practice:

- Revolutionary Oncology Agents: Many first‐in‐class drugs, particularly in oncology, have offered new hope to patients with few alternatives. For instance, drugs such as the first–approved monoclonal antibodies or inhibitors targeting novel epigenetic regulators (e.g., EZH2 inhibitors) have redefined the treatment of certain sarcomas or hematologic malignancies by introducing a novel therapeutic pathway.

- Orphan Drug Approvals: A significant fraction of first–in–class drugs are also developed as orphan drugs. For example, innovative compounds like lonafarnib (a farnesyltransferase inhibitor) have gained approval to treat rare diseases by targeting previously untapped biological pathways. These groundbreaking therapies provide tangible examples of how first–in–class drugs serve critical niche areas where traditional therapies have failed to deliver substantial benefits.

- Comparative Evidence in Clinical Trials: Case–studies described in research often illustrate that first‐in‐class drugs achieve breakthrough status when early clinical data support a significant improvement over the standard-of-care. Often, the documentation of a new receptor or pathway being targeted is accompanied by detailed mechanistic studies, expansive biomarker–driven patient stratification, and adaptive trial protocols.

Market and Competitive Advantages

From a commercial viewpoint, first‐in‐class drugs have unique market characteristics:

- First–Mover Advantages: As the pioneers in their therapeutic area, first–in–class drugs often benefit from brand recognition and market exclusivity—at least for the period before competitors introduce follow–on products that may refine the drug’s profile. This early market presence can translate into sustained revenue, increased investment, and a strong influence on prescribing practices.

- Regulatory and Pricing Incentives: Owing to their innovative nature, first‐in‐class drugs often receive special regulatory designations that not only expedite their market entry but also confer extended exclusivity periods. These incentives are particularly appealing in therapeutic areas marked by high unmet needs. Additionally, if a first‐in‐class drug demonstrates clear clinical benefit, it may receive premium pricing and favorable reimbursement decisions which further consolidate its competitive advantage.

- Catalyst for Subsequent Innovation: The launch of a first‐in‐class drug often sets off a wave of follow–on innovation. Although many follow–on drugs are eventually classified as “me-too” or incremental improvements, the initial breakthrough can create a robust innovation ecosystem where multiple manufacturers subsequently compete, leading to overall improved treatment options for patients.

Challenges and Risks

Despite the immense potential, being designated as first‐in‐class is accompanied by significant challenges:

- High Attrition Rates in Clinical Development: Clinical trials for first–in–class drugs are inherently risky because the novel mechanism may harbor unforeseen side effects or have unpredictable efficacy outcomes. Historically, many first–in–class candidates fail in clinical stages due to issues related to toxicity, off-target effects, or simply suboptimal therapeutic effects.

- Regulatory Uncertainty: Although expedited pathways exist, regulators require robust evidence in the form of clinical and mechanistic data. This dual requirement often translates into longer development times and higher financial risk. Moreover, while breakthrough designations facilitate early market access, post–marketing surveillance may reveal adverse events that were not anticipated in clinical trials, thereby affecting the drug’s long-term safety profile.

- Market Competition Dynamics: The initial exclusivity enjoyed by first–in–class drugs can be eroded if competitors develop best‐in‐class drugs that offer improved efficacy or safety profiles. In such cases, the commercial advantage of the pioneer is challenged, and market share can shift quickly to those subsequent drugs, impacting the overall return on investment.

- Complexity of Development and Manufacturing: First–in‐class drugs, particularly those that target novel or “undruggable” proteins, often require innovative manufacturing processes, specialized formulation strategies, and rigorous quality–control measures. All these add layers of complexity and cost that must be managed by the sponsoring company.

Conclusion

In summary, to be considered “first‐in‐class,” a drug must fulfill several stringent criteria that cut across scientific innovation, clinical need, regulatory acceptance, and market dynamics. First–in–class drugs are defined primarily by their novel mechanism of action—a target or pathway that has not been exploited before—and by their potential to address a significant unmet medical need, often in disease areas where conventional therapies do not suffice. The evaluation of such drugs begins in the early days of drug discovery through robust preclinical testing and advanced computational modeling and continues as the drug moves through carefully designed clinical trial phases that include adaptive and innovative study designs. Regulatory considerations further cement this status through designations like Breakthrough Therapy, Fast Track, or Priority Review, allowing these products to access expedited review pathways while ensuring vigilance through rigorous post–marketing surveillance.

The impact of first‐in‐class drugs extends beyond clinical innovation; they re–shape market dynamics by establishing a precedent for follow–on competitors and forming a basis for future drug innovation. Successful case studies in oncology and rare diseases have demonstrated that first–in‐class therapies can provide dramatic improvements in patient management when compared to traditional treatments. However, the high attrition rates during clinical trials, significant development risks, and ongoing regulatory scrutiny present persistent challenges. The commercial environment is equally demanding as first–in‐class drugs must maintain their early–mover advantage even as “best‐in‐class” drugs eventually emerge to provide refined treatment options.

Ultimately, the designation of first‐in‐class is a multi–dimensional evaluation process—requiring a convergence of novel scientific discovery, fulfillment of an unmet medical void, and meeting rigorous regulatory standards. With an increased understanding of complex biological systems and the advent of innovative technologies in drug discovery, the landscape of first‐in‐class therapeutics is continuously evolving. This evolution promises improved patient outcomes and a dynamic shift toward more personalized and effective therapies while also demanding constant vigilance concerning safety and long–term efficacy. Moving forward, pharmaceutical innovators and regulatory bodies alike must balance the excitement of breakthrough therapies with the practical challenges inherent in developing and approving drugs that truly transform clinical practice.

In conclusion, a drug is considered “first‐in‐class” if it demonstrates a truly novel mechanism of action that is distinct from existing therapies, addresses a significant unmet medical need, and meets the stringent criteria set forth in clinical research and regulatory review. Success in this category not only opens new therapeutic horizons for patients but also fuels further innovation in drug development, despite the attendant risks and challenges associated with pioneering a new pharmacological landscape.

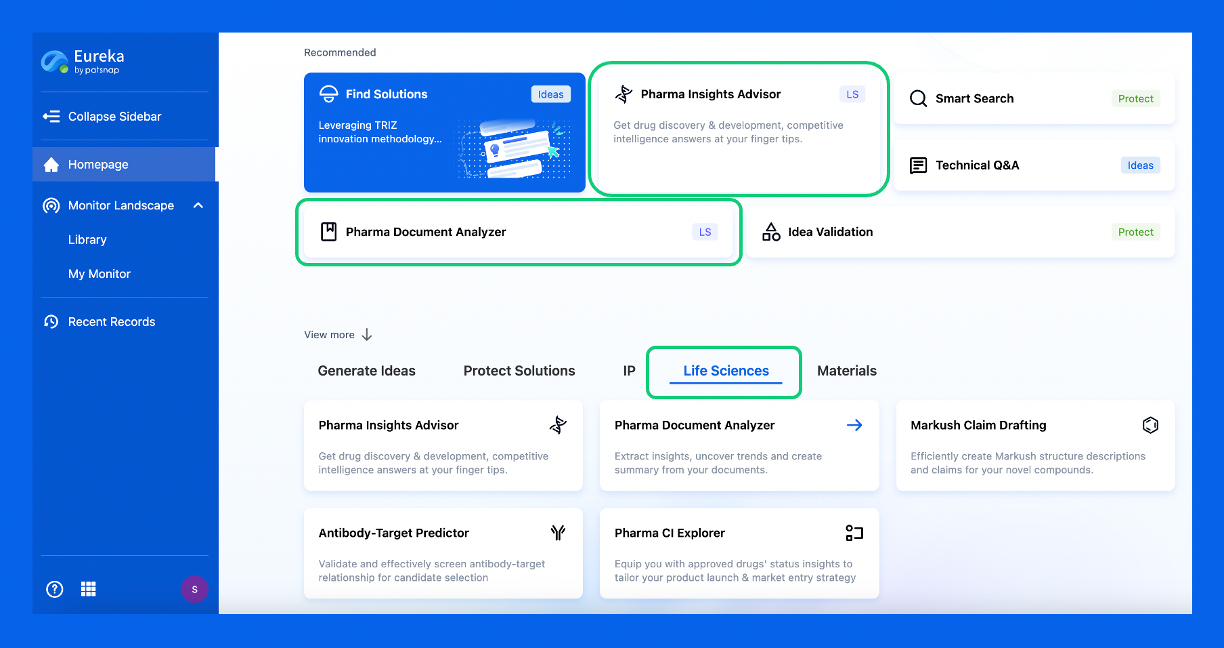

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.