What are the new drugs for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)?

Overview of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)

NASH is a major clinical concern as it represents a progressive stage of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) that can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure. Over many years of research, scientists have come to understand that NASH reflects not only hepatic fat accumulation but also a complex interplay among metabolic derangements, inflammation and fibrotic processes. Many new drugs are under development to address this multi‐factorial disease because the current treatment options (largely focused on lifestyle modifications or limited off‐label use of insulin sensitizers) remain inadequate in terms of long‐term outcomes and safety.

Definition and Pathophysiology

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is defined by the histologic presence of steatosis (fatty infiltration), inflammation and hepatocellular injury (with ballooning of hepatocytes) that can eventually lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis. Its pathophysiology is multifaceted. Factors including insulin resistance, dysregulated lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, lipotoxicity, endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction have been implicated. In addition, crosstalk between the liver and adipose tissue or gut influences inflammation and progression of fibrosis. Many genetic as well as epigenetic factors add to the heterogeneity seen among NASH patients. These interconnected pathways have guided researchers to design drugs that can target one or more of these mechanisms simultaneously.

Current Treatment Landscape

At present, there is no approved pharmacotherapy labeled for NASH in most key markets such as the United States and Europe. Standard care involves lifestyle interventions including diet modifications, exercise and weight reduction. Off‐label medications such as pioglitazone and vitamin E have been used in selected patients; however, limitations in efficacy and safety have prompted intense research into more effective, mechanism‐based agents. With an expanding pipeline, pharmaceutical companies have focused on molecules targeting nuclear receptors, anti‐inflammatory/cytokine pathways, apoptosis signal regulators and fibrosis modulators, among others. As clinicians and researchers await breakthrough approvals, the need for new drugs that not only reduce steatosis but also reverse liver injury and fibrosis has never been greater.

New Drug Developments for NASH

Recent years have witnessed the testing of many novel drug candidates in phase II and phase III clinical trials. These candidates include both small molecules and biologics. Some of them have recently achieved accelerated or conditional approval in some regions while others are in the late‐stage clinical testing phase. Here we examine both recently approved agents and those in late-stage trials.

Recently Approved Drugs

One of the most exciting breakthroughs has been the recent accelerated regulatory consideration of resmetirom. Resmetirom is a selective thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR‐β) agonist that has shown robust improvements in not only hepatic lipid parameters but also in markers of inflammation and fibrosis. In phase III clinical trials, resmetirom demonstrated statistically significant reductions in liver fat content and improvements in key biochemical markers, leading to accelerated approval in some jurisdictions. Its clinical readouts include improvements in NASH resolution in patients with stage 2 and stage 3 fibrosis. This approval marks the first time a drug specifically addressing metabolic dysfunction‐associated steatohepatitis (MASH, as many now call NASH) has reached regulatory milestones, providing hope for standardized therapy soon.

Other agents have also received accelerated review or positive interim data in recent years. Although not yet fully approved, drugs such as obeticholic acid—a farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist—have come under intense scrutiny because of their demonstrated ability to improve fibrosis. In interim analyses of phase III trials (for example, the REGENERATE study), obeticholic acid has shown dose‐dependent improvements in fibrosis stage without worsening NASH, although some concerns regarding pruritus and cardiovascular lipoprotein alterations have been raised. In summary, among the recently approved or provisionally approved agents, resmetirom stands out as a pivotal breakthrough while others may soon be approved based on positive phase III data.

Drugs in Late-Stage Clinical Trials

Apart from resmetirom and obeticholic acid, several other new drug candidates are in late‐phase clinical trials showing promising results.

• Elafibranor, a dual PPAR‐α/δ agonist developed by Genfit, has been evaluated extensively in phase II/III trials. Although earlier studies gave mixed results, updated trial designs continue to assess whether targeting both fatty acid oxidation and inflammation can yield NASH resolution and fibrosis improvement.

• Cenicriviroc is another promising candidate that targets inflammation and fibrosis by antagonizing chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5. In phase II trials (such as CENTAUR), cenicriviroc showed improvements in liver fibrosis without worsening steatohepatitis. Currently, phase III trials are underway to confirm these effects in larger patient populations.

• Lanifibranor, a pan‐PPAR agonist, is designed to target multiple metabolic pathways and exert anti‐inflammatory, antifibrotic and insulin sensitizing effects. In clinical trials, lanifibranor has demonstrated improvements in both NASH resolution and fibrosis, leading to its investigation in phase III trials.

• Aramchol, an SCD‐1 modulator, aims to reduce de novo lipogenesis and improve hepatic lipid handling. Early phase II results pointed toward significant reductions in liver fat content and improvements in liver biochemistry, and a phase III trial (ARMOR study) is currently evaluating its efficacy in advanced fibrosis with positive trends noted.

• VK2809, a liver‐directed THR‐β agonist distinct from resmetirom, and pegbelfermin, a PEGylated fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) analogue, are other agents in advanced phases of development. VK2809 has produced significant reductions in hepatic fat as measured by MRI‐PDFF, and pegbelfermin has shown improvements in metabolic parameters and liver fat with a favorable safety profile in smaller studies.

Collectively, these drugs in late‐stage clinical trials are addressing different components of NASH pathophysiology and hold promise for next‐generation treatments.

Mechanisms of Action

Given the multifactorial nature of NASH, the new drugs under development target various mechanisms. A detailed understanding of these mechanisms helps in tailoring combinations or determining patient subgroups that may benefit most.

Drug Mechanisms and Targets

Several principal mechanisms are being leveraged:

• Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta (THR‐β) Agonism – Resmetirom and VK2809 work via selective engagement of the THR‐β receptor. Activation of THR‐β improves hepatic lipid metabolism; increases fatty acid oxidation; and reduces lipogenesis, inflammation and, ultimately, fibrosis. This mechanism is attractive as it targets the core metabolic dysfunction present in NASH.

• Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) Agonism – Obeticholic acid belongs to this class. FXR agonists regulate bile acid synthesis, lipid metabolism, and reduce hepatic inflammation. By modulating gene expression in hepatocytes and stellate cells, FXR agonists help attenuate fibrosis. However, they are sometimes associated with side effects such as pruritus and alterations in lipid profiles.

• Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) Modulation – Drugs like elafibranor (dual PPAR‐α/δ agonist) and lanifibranor (pan‐PPAR agonist) activate nuclear receptors that regulate fatty acid oxidation, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation. PPAR activation can lead to improvements in liver steatosis and anti‐fibrotic effects by reducing cytokine release and inhibiting stellate cell activation.

• Chemokine Receptor Antagonism – Cenicriviroc targets CCR2 and CCR5, reducing recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and preventing fibrotic progression. This approach focuses on dampening the chronic inflammatory response that drives fibrosis in NASH.

• SCD-1 Modulation – Aramchol modulates stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 activity, thus reducing de novo lipogenesis and hepatic lipid storage. This reduction in hepatic lipogenesis can directly lower liver fat content and potentially improve liver histology.

• FGF21 Pathway Modulation – Pegbelfermin, as an FGF21 analogue, mimics the effects of this hormone by improving insulin sensitivity, reducing body weight and hepatic steatosis, and exerting anti-inflammatory effects.

Comparison of Different Mechanisms

Each drug class offers unique benefits and potential drawbacks. For instance, THR‐β agonists like resmetirom have generated robust lipid‐lowering effects and may be preferable in patients with significant metabolic dysfunction; however, long‐term effects on cardiac function or bone density are still under evaluation. FXR agonists such as obeticholic acid very effectively improve fibrosis scores but may require careful monitoring of pruritus and lipoprotein levels. In contrast, PPAR modulators such as elafibranor and lanifibranor deliver a broader spectrum effect by targeting lipid metabolism, glucose regulation and inflammatory cascades simultaneously, although patient selection and dose optimization remain challenges. Furthermore, agents targeting inflammation (cenicriviroc) or lipogenesis (aramchol) are promising in patient subsets with dominant inflammatory or metabolic phenotypes. Hence, a combination approach tailored to an individual’s signal‐driving pathway may represent the future therapeutic strategy for NASH.

Efficacy and Safety

Efficacy and safety are critical in a disease where long‐term therapy is required and patient comorbidities (such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes) complicate treatment.

Clinical Trial Results

New drug candidates for NASH have been evaluated using various endpoints, including liver histology, noninvasive imaging (MRI‐PDFF), and reductions in biomarkers of liver injury.

• Resmetirom, for example, in recent phase III trials provided significant improvements in liver fat reduction (quantitatively assessed using MRI–PDFF) and a meaningful histological response on NASH resolution in patients with stage 2/3 fibrosis.

• Obeticholic acid has demonstrated dose‐dependent improvements in fibrosis stage without worsening NASH. Although there were improvements in some biochemical markers, the lack of significant NASH resolution in certain subgroups and side effects like pruritus have been points of concern.

• Lanifibranor in phase II and ongoing phase III studies has shown evidence of both NASH resolution and improvement in fibrosis score, suggesting a favorable impact on liver histology.

• Cenicriviroc, as reported in phase II trials, improved measurable fibrosis endpoints compared to placebo, though its impact on NASH resolution, separately, is still being evaluated in larger phase III studies.

• Aramchol, VK2809 and pegbelfermin have also provided encouraging data from early phase studies regarding liver fat, steatosis and metabolic improvements, which are being further substantiated in phase III trials.

These results underscore that many new drugs are showing clinically significant changes in key histological endpoints while also improving noninvasive markers, though differences in trial design and patient heterogeneity make direct comparisons challenging.

Safety Profiles and Side Effects

Safety remains a centralized question in the evaluation of NASH drugs because many patients have metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors.

• Resmetirom has appeared to have an acceptable safety profile with minimal adverse events reported in phase III studies. The thyroid hormone receptor selectivity is designed to reduce systemic off-target effects; however, long-term safety data will be needed to confirm its cardiovascular and skeletal safety.

• Obeticholic acid, while effective in improving fibrosis, has been associated with pruritus and potential increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; careful patient monitoring is therefore necessary when using FXR agonists.

• PPAR agonists such as elafibranor and lanifibranor have shown promising efficacy; however, concerns regarding weight gain, fluid retention or off-target effects on muscle and bone metabolism remain under active investigation, especially in larger and more diverse patient populations.

• Cenicriviroc’s side effects in phase II studies were generally mild, though the anti-inflammatory mechanism may predispose to immunosuppression if dosed at higher levels; however, ongoing trials will clarify whether a therapeutic window exists that minimizes such risks.

• Aramchol and VK2809 have so far shown dose‐dependent tolerability with manageable adverse events, but as these drugs are combined with other medications in real‐world settings, the possibility of drug–drug interactions must be evaluated carefully.

• Pegbelfermin demonstrated a good safety profile in early clinical trials with injection-related discomfort being the most notable adverse effect. Overall, the side‐effect profiles of these drugs are carefully balanced by dosing strategies, patient selection and monitoring protocols, highlighting the need for a personalized approach.

In aggregate, while a range of new agents is showing efficacy in improving histological and biochemical markers of NASH, long‐term studies are necessary to assess durability of response, long-term safety and effects on clinical outcomes such as progression to cirrhosis or liver transplantation.

Future Directions

The evolving field of NASH therapeutics points to exciting opportunities as well as significant challenges that must be addressed to yield a long-term, safe treatment paradigm.

Emerging Therapies

Emerging therapies in NASH are focused not only on monotherapy but also on combination treatments that target different pathogenic pathways simultaneously. There is growing interest in strategies that combine metabolic modulation, anti-inflammatory action and antifibrotic effects. For example:

• Combination regimens that might include a THR‐β agonist with an anti‐inflammatory agent (such as cenicriviroc) are being considered to maximize multi‐target effects without additive toxicity.

• Other innovative approaches include novel formulations of naturally derived compounds or nanomedicine‐based delivery systems that enhance drug delivery to the liver while limiting systemic exposure.

• Research is also ongoing into gene‐silencing techniques such as RNA interference (siRNA) strategies against specific metabolic targets, which may eventually be integrated into a precision medicine approach tailored to a patient’s genetic risk factors.

• Biomarker development for stratifying patients and predicting response to individual drugs or combinations is also gaining traction. It is hoped that the future “gold standard” for NASH treatment will involve personalized regimens, potentially guided by noninvasive markers that track inflammation, fibrosis and metabolic changes simultaneously.

Research and Development Challenges

Despite the promise shown by many novel agents, several challenges remain:

• Heterogeneity of the disease: NASH is not a uniform condition. The wide variation in histologic features, patient backgrounds and concomitant metabolic diseases makes it difficult to design one single “magic bullet” therapy. This lack of uniformity is also a challenge for clinical trial design and the ultimate regulatory strategy.

• Long clinical trial durations: Because endpoints in NASH trials rely on histologic improvements (which may take at least 12 to 18 months to manifest) as well as eventual clinical outcomes, trials are long and expensive. This prolongs the time to discover whether a candidate agent truly changes the course of disease.

• Safety and tolerability: Balancing efficacy with acceptable side-effect profiles is critical. With many NASH patients already suffering from comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, new drugs must additionally demonstrate that they do not exacerbate these conditions.

• Regulatory and biomarker validation: With no universally accepted surrogate biomarkers for long-term outcomes, both the regulatory agencies and the industry continue to work on new composite endpoints that reflect meaningful clinical improvements. Increasing the reliability and validation of noninvasive tests (e.g. imaging data, blood biomarkers) is paramount to reducing the dependence on liver biopsies.

• Combination therapies: While combinations are appealing from a mechanism standpoint, there are significant regulatory and manufacturing challenges in ensuring that combinations are both safe and synergistic. Determining optimal doses for individual agents when combined—and predicting interactions—remain challenging.

• Scalability and cost: Some emerging therapies, especially those based on novel delivery systems like nanomedicine or gene‐silencing, face challenges in cost‐effectiveness and manufacturing consistency. Addressing these issues will be vital for broad clinical adoption.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the development of new drugs for NASH has entered a very promising phase. The expanding pipeline includes agents that target different aspects of the disease—from metabolic dysfunction and steatosis (THR‐β agonists like resmetirom and VK2809) to inflammation (cenicriviroc) and fibrogenesis (FXR agonists such as obeticholic acid, and pan‐PPAR agonists like lanifibranor) as well as modulators of lipogenesis (aramchol). Each drug class employs a distinct mechanism and offers potential advantages and limitations in terms of both efficacy and safety. Clinical trial data from phase II and phase III studies indicate that many of these agents produce statistically significant improvements in liver fat, inflammation markers and fibrosis, although variability remains between agents and patient subgroups.

From a mechanistic perspective, targeting nuclear receptors, chemokine pathways, and hormonal regulators of lipid metabolism illustrates how multi‐targeted therapies may be the key to treating a heterogeneous condition such as NASH. The emerging trend appears to be the development of combination therapies and personalized treatment approaches based on noninvasive biomarkers and patient-specific factors. Safety profiles are under constant review, and while many drugs have acceptable adverse event profiles in early and mid‐term studies, long‐term data are essential to evaluating their impact on broader clinical outcomes.

Future directions in NASH drug development are geared toward fine-tuning combination regimens, improving biomarker validation for patient selection and treatment monitoring, and establishing scalable manufacturing techniques that ensure cost-effectiveness and reproducibility. Furthermore, as the regulatory landscape evolves in tandem with scientific advances, it is anticipated that new endpoints and surrogate markers will expedite the approval process for these novel agents. In turn, this may eventually lead to a robust portfolio of tailored, patient-specific therapies that address the full spectrum of NASH pathophysiology.

Overall, the new drugs for NASH represent a multi-pronged attack on a complex disease paradigm. While resmetirom’s recent accelerated approval marks a significant milestone, several other agents—including obeticholic acid, elafibranor, cenicriviroc, lanifibranor, aramchol, VK2809 and pegbelfermin—are progressing through late-stage trials with promising results. The challenge now lies in replicating these outcomes in long-term studies and integrating them into clinical practice in a way that reduces overall risk while improving outcomes for a patient population that is highly vulnerable to progressive liver failure and cardiovascular complications. The field is dynamic, and ongoing research not only continues to test individual drugs but is also exploring combination strategies that could ultimately deliver a more comprehensive disease-modifying approach. With the promise of personalized therapy on the horizon and a deeper understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, it is expected that within the next several years we will see a paradigm shift in the treatment of NASH.

In summary, many novel agents have been developed and tested for NASH, each addressing different biological pathways. While resmetirom now stands as a milestone drug with accelerated approval, agents such as obeticholic acid, elafibranor, cenicriviroc, lanifibranor, aramchol, VK2809 and pegbelfermin represent the future of NASH therapy. Each of these drugs brings its own spectrum of efficacy and safety profiles and will likely be used in specific patient subgroups or in combination, based on individual disease characteristics. The future is geared toward individualized treatments, rigorous safety assessment and the use of advanced noninvasive biomarkers, which together will refine therapeutic choices for this unmet medical need.

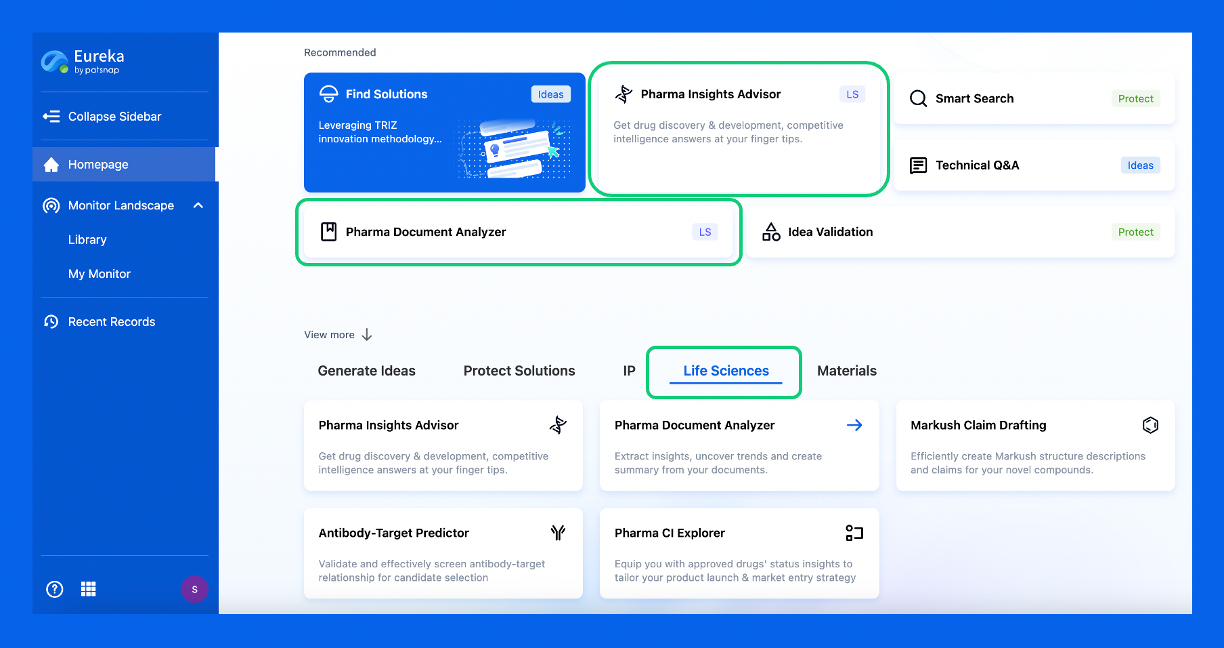

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.