Request Demo

What are the therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR?

11 March 2025

Introduction to EGFR

EGFR Function and Significance

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a central role in regulating cell survival, growth, differentiation, and migration. This receptor is involved in transmitting signals from its extracellular ligands—such as epidermal growth factor (EGF)—into intracellular signaling cascades such as the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. EGFR activation triggers phosphorylation events on its cytoplasmic tail that allow binding of adaptor proteins and thus modulate gene expression, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis. Consequently, EGFR is not only essential for normal cellular functions but is also critical in developmental processes and tissue homeostasis. Its ability to maintain cellular functions underlies the interest in targeting EGFR in situations where its signaling becomes deregulated.

Role of EGFR in Disease Pathogenesis

Aberrant EGFR signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous cancers and other diseases. Overexpression of the EGFR protein is detected in many solid tumors—such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), colorectal cancer, and glioblastoma—as well as in some inflammatory and other non-neoplastic conditions. EGFR mutations, gene amplification, or splice variants (like EGFRvIII) lead to constitutive activation that drives uncontrolled cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Such aberrations often result in aggressive tumor behavior, poorer prognosis, and resistance to conventional therapies. This clear involvement of EGFR in cancer progression makes the receptor a prime target for therapeutic intervention.

Therapeutic Candidates Targeting EGFR

Current Approved Therapies

Over the past two decades, several therapeutic candidates that directly target EGFR have been approved across multiple indications.

• Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are the earliest and most established class of EGFR therapies. Agents such as cetuximab and panitumumab bind to the extracellular domain of EGFR, preventing ligand binding and receptor dimerization. Cetuximab, in particular, was one of the first anti-EGFR antibodies approved and has been used in colorectal cancer and head and neck cancers. Panitumumab, a fully human mAb, is also approved predominantly in metastatic colorectal cancer for patients with wild-type RAS tumors.

• Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) represent another class of approved EGFR-targeting drugs. Examples include erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, and dacomitinib. These agents are orally bioavailable and work by binding to the ATP binding site of the EGFR intracellular kinase domain, hence blocking receptor autophosphorylation and downstream signaling. They have been extensively used in NSCLC patients harboring EGFR mutations.

• Other formulations include antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) that utilize the specificity of mAbs coupled with potent cytotoxic payloads. Although these are at an earlier stage of approval compared with mAbs and TKIs, some ADCs are available for clinical use and are continuously being evaluated.

These therapies have been incorporated into clinical practice with established dosing guidelines and robust supporting clinical trial results. Their approval has been based on demonstrated improvements in progression-free survival, overall response rates, and quality‐of‐life measures across selected cancer subtypes.

Emerging Therapeutic Candidates

Alongside the established therapies, several emerging candidates are now under clinical evaluation or in preclinical development. These candidates aim to address some of the limitations found in the current approved therapies.

• Next-generation EGFR TKIs such as osimertinib have been developed to overcome resistance mutations (for example, the T790M mutation) that arise after initial treatment with first-generation EGFR inhibitors. Osimertinib is notable for its ability to target both sensitizing and resistant EGFR mutations and is now approved for second-line therapy in NSCLC. Its clinical development is supported by strong pharmacodynamic data and robust clinical trial outcomes.

• Irreversible inhibitors and multi-target inhibitors are also being developed. These drugs bind covalently to the EGFR kinase domain and have mechanisms to block multiple members of the EGFR family simultaneously. Such agents—including combinations of EGFR-TKIs with HER2 inhibitory properties (dual inhibitors) or inhibitors with broader spectrum activity—are currently being evaluated in phase II and III clinical trials. Their development is driven by the need to delay or overcome acquired resistance that frequently limits the effectiveness of reversible inhibitors.

• Bispecific antibodies and engineered antibody fragments (such as nanobodies or single-chain variable fragments, scFv) are being explored as alternatives to full-size mAbs. These engineered constructs are smaller in size, potentially allowing greater tissue penetration and faster clearance. Their ability to target two independent epitopes simultaneously (often on EGFR or both EGFR and another relevant receptor such as HER2) may lead to an enhanced anti-tumor response while reducing immunogenicity and adverse events.

• Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) continue to be optimized. Novel conjugation strategies, improved linker technologies, and optimized payloads are in development to overcome the limitations of off-target toxicity seen with earlier ADCs. These improved ADCs enhance the delivery of cytotoxic agents specifically to EGFR-overexpressing tumors while sparing normal tissue, potentially leading to improved therapeutic indices.

• In addition to direct EGFR inhibitors, agents targeting downstream or parallel pathways are being developed as combination therapies to overcome resistance. For example, combining EGFR inhibitors with PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors or anti-angiogenic agents (such as bevacizumab) is under investigation. Such combination therapies may block compensatory pathways that allow tumors to evade the effects of single-agent EGFR inhibition.

Mechanism of Action

How Therapies Target EGFR

Therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR work via various molecular strategies to inhibit receptor activation and downstream signaling.

• Monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab bind to the extracellular domain of EGFR to block the binding of natural ligands like EGF and transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α). This action prevents receptor dimerization—a necessary step for receptor activation—and subsequent autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues. In addition, such antibodies can induce receptor internalization and degradation and may also stimulate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), thereby enlisting the immune system to target tumor cells.

• Small molecule TKIs like erlotinib, gefitinib, and afatinib are designed to compete with ATP for binding at the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR. By doing so, they inhibit its autophosphorylation and the activation of downstream signaling cascades including the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways. These inhibitors vary based on whether they are reversible or irreversible. For example, first-generation TKIs bind reversibly, whereas later-generation compounds such as osimertinib bind irreversibly, accounting for their increased potency against certain resistance mutations.

• Bispecific antibodies and engineered smaller antibody fragments operate by simultaneously engaging distinct epitopes and potentially blocking multiple receptor interactions at once. This approach may result in more complete inhibition of EGFR signaling either by blocking ligand binding and receptor dimerization more efficiently or by reducing tumor cell resistance through downregulation of EGFR protein levels.

Differences in Mechanism Among Candidates

Despite targeting the same receptor, the therapeutic candidates differ markedly in their mechanism of action, pharmacodynamics, and clinical application.

• The difference between mAbs and TKIs is fundamental. mAbs target the extracellular region and generally lead to receptor downregulation and ADCC, while TKIs work intracellularly to prevent kinase activity. These differences manifest in the pharmacokinetic profiles – mAbs are typically infused with a long half-life while TKIs are orally administered with shorter half-lives.

• Among TKIs, reversible inhibitors (like erlotinib and gefitinib) cause transient inhibition of EGFR kinase activity, whereas irreversible inhibitors (such as osimertinib and dacomitinib) form a covalent bond with EGFR, leading to longer-lasting effects. This irreversible binding is especially beneficial for targeting resistant mutations that may otherwise allow for receptor reactivation in the presence of reversible inhibition.

• Engineered antibody fragments and bispecific constructs provide advantages in terms of tumor penetration and clearance. Their reduced molecular size and the ability to target two separate epitopes enable them to overcome some of the dosing and biodistribution challenges seen with conventional monoclonal antibodies.

• Combination therapeutics further differentiate themselves by addressing compensatory mechanisms that single agents may not cover. For example, while EGFR inhibitors block the primary signaling pathway, combinations that include inhibitors of the downstream PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and angiogenesis inhibitors broaden the blockade to secondary escape routes used by tumors, thus potentially producing a more robust and durable clinical response.

Clinical Trials and Efficacy

Overview of Key Clinical Trials

Extensive clinical trial programs have validated both the approved and emerging EGFR-targeting candidates in various cancer types.

• Early phase trials for cetuximab and gefitinib demonstrated objective tumor regression and improvements in progression-free survival for patients with EGFR-driven tumors, leading to their subsequent approval. Key trials in NSCLC and colorectal cancer established response rates and survival benefits that supported the broader clinical adoption of these agents.

• Subsequent trials with next-generation inhibitors, such as osimertinib, have focused on overcoming resistance. For instance, the clinical trial programs for osimertinib demonstrated efficacy in patients with acquired T790M mutations after failure of first-generation TKIs, with improved progression-free survival and tolerable safety profiles.

• Moreover, clinical studies examining combination regimens—such as the addition of bevacizumab (an anti-VEGF antibody) to EGFR inhibitors—have produced mixed but promising results with enhanced efficacy in some patient subgroups. Trials investigating bispecific antibodies and ADCs are ongoing and are designed to optimize dosing while reducing toxicity.

• Other studies are addressing the role of engineered antibody fragments and the use of liquid biopsies to monitor treatment resistance and adapt therapeutic strategies accordingly. These trials contribute essential data on the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and immune-mediated effects of the novel agents under development.

Efficacy and Safety Profiles

Clinical trial data reveal that the efficacy and safety of EGFR-targeting therapies can vary greatly based on patient genetics, tumor type, and treatment regimen.

• Approved mAbs offer substantial benefits in patients with EGFR-overexpressing tumors. For example, cetuximab has provided significant improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival in colorectal cancer patients with wild-type KRAS. However, as with many antibody-based therapies, infusion-related reactions and skin toxicities are common adverse events.

• TKIs are generally well tolerated in patients with NSCLC. Erlotinib and gefitinib have shown robust responses in patients with activating EGFR mutations, predominantly in adenocarcinoma histologies and among non-smokers. Their common adverse effects include rash and diarrhea but these are usually manageable. Next-generation TKIs like osimertinib have improved safety profiles due to greater specificity for mutant EGFR and lower off-target activity. The irreversible binding nature of these inhibitors leads to sustained receptor inhibition and is associated with higher rates of response in resistant populations.

• Emerging candidates such as bispecific antibodies and ADCs are still undergoing rigorous evaluation. Early-phase studies suggest that these agents may combine high antitumor efficacy with reduced systemic toxicity owing to the targeted delivery of cytotoxins. However, further trials are needed to confirm long-term safety and to optimize delivery parameters, as immunogenicity and off-target effects remain potential concerns.

• Combination therapies, which include dual inhibition strategies addressing compensatory pathways, have shown potential for better clinical outcomes in patients with refractory disease. Combined EGFR and VEGF inhibitors, for instance, may enhance tumor control but also exhibit additive toxicities that require careful management.

Challenges and Future Directions

Resistance and Limitations

Despite the success of EGFR-targeted approaches, several challenges and mechanisms of resistance continue to hinder long-term efficacy.

• Intrinsic and acquired resistance are major obstacles. Common mechanisms include secondary mutations in the EGFR kinase domain (such as T790M), activation of alternate signaling pathways (including MET amplification, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway activation), and phenotypic changes including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). These resistance mechanisms reduce the effectiveness of both mAbs and TKIs over time and necessitate the development of next-generation inhibitors.

• Drug tolerance emerges from heterogeneous tumor cell populations. Variation in EGFR expression, receptor dimerization states, and interactions with other membrane receptors (e.g., HER2) further contribute to resistance. In many cases, even after a period of effective therapy, the tumor may evolve multiple bypass tracks that allow continued growth.

• Safety issues, such as skin rash, gastrointestinal disturbances, and, in some cases, cardiotoxicity (notably observed with HER2-directed agents that share pathways with EGFR inhibitors), are additional limitations in the clinical use of these drugs. Adverse effects must be balanced against clinical benefits, particularly in combination regimens.

• Furthermore, inter-patient variability based on genetic markers (such as EGFR mutation status and copy number), ethnic differences, and prior treatment history present challenges in choosing the ideal therapy and dosing regimens. The absence of robust predictive biomarkers that can definitively stratify patients for maximum benefit remains a significant gap in personalized medicine.

Future Research and Development

Research continues to drive the evolution of EGFR-targeting strategies in several directions.

• Development efforts are focused on next-generation TKIs that not only target the common sensitivity mutations but also have activity against resistant variants. New compounds are being designed using structure-based drug design and molecular modeling, which allows for the identification of novel binding pockets and allosteric sites on the EGFR kinase domain. These efforts aim to produce inhibitors with enhanced potency, selectivity, and a lower propensity for resistance.

• Combination therapies are under active investigation to overcome compensatory resistance mechanisms. Trials combining EGFR inhibitors with agents that inhibit signaling pathways downstream (such as PI3K, Akt, or mTOR inhibitors) or parallel pathways (such as MET inhibitors or anti-angiogenic agents like bevacizumab) are underway. The goal is to achieve a more comprehensive blockade of cellular signaling that circumvents multiple resistance routes.

• Efforts are also being made to develop bispecific antibodies capable of engaging not only EGFR but also other related receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., HER2). These agents promise to overcome receptor heterogeneity and co-activation that often contribute to drug resistance. Engineering of these antibodies to optimize tumor penetration and to reduce immunogenicity is a high priority in the field.

• In addition, newer antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) with improved drug-to-antibody ratios, more stable linkers, and more potent cytotoxic agents are being explored. These ADCs are designed to deliver high concentrations of chemotherapy selectively to EGFR-positive tumor cells, sparing normal tissues and reducing systemic toxicity.

• Biomarker development, including the use of liquid biopsies and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), is emerging as a promising tool to monitor therapeutic responses and the evolution of resistance mechanisms. This will enable dynamic adjustment of therapy and may facilitate the earlier identification of resistance, allowing clinicians to switch therapies or initiate combination regimens promptly.

• Nanotechnology and novel delivery systems are also being investigated. These approaches may increase drug concentration at the tumor site while reducing off-target exposure and adverse effects. For example, nanoparticle-based delivery of EGFR inhibitors or ADCs may enhance penetration into solid tumors and improve therapeutic outcomes.

• Moreover, ongoing research is addressing the modulation of the immune microenvironment in combination with EGFR-targeted therapies. Emerging evidence suggests that immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with EGFR inhibitors may lead to synergistic effects, particularly in tumors expressing high levels of EGFR. Understanding the interplay between EGFR signaling and immune response is an area of active investigation that may yield novel combination strategies.

• Finally, resistance mechanisms associated with non-genomic changes, such as epigenetic modifications and microRNA regulation, are increasingly recognized as important factors in therapeutic failure. Future developments may include epigenetic modifiers combined with EGFR-targeting agents to re-sensitize tumors to treatment. These multimodal approaches have the potential to provide a more durable response by targeting both the genomic and non-genomic drivers of resistance.

Conclusion

In summary, the therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR encompass a broad spectrum of molecular agents that range from fully approved monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab, panitumumab) and small molecule TKIs (erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, dacomitinib) to emerging agents such as next-generation inhibitors (osimertinib), bispecific antibodies, ADCs, and engineered antibody fragments. Each candidate targets EGFR through distinct yet sometimes overlapping mechanisms. Monoclonal antibodies intercept ligand binding and promote receptor internalization and immune-mediated killing, whereas TKIs competitively inhibit the ATP-binding site, thereby blocking intracellular signaling cascades. Researchers have also innovated in the realm of nanotechnology and combined modality therapies to thwart the common challenge of drug resistance and achieve more targeted delivery with fewer side effects.

Clinical trials spanning early phase to pivotal registrational studies have provided robust data on the efficacy and safety profiles of these agents. They highlight improvements in progression-free survival, overall responses, and in select patient populations, overall survival benefits. The accumulated evidence demonstrates that while the first-generation EGFR inhibitors are effective in certain genomic contexts, acquired resistance remains a critical challenge. To address this, combination therapies targeting parallel pathways (for example, VEGF or PI3K/Akt/mTOR) or employing next-generation irreversible inhibitors are being actively developed and show promising results.

Nevertheless, despite these advances, the continued evolution of resistance—through mechanisms such as secondary mutations, bypass signaling, and EMT—necessitates further research. Future studies directed toward innovative inhibitor designs, optimized combination regimens, and the integration of advanced biomarker strategies (including ctDNA monitoring) will likely improve patient selection and provide more durable responses. Moreover, as our understanding of the interplay between EGFR signaling and the tumor microenvironment advances, novel therapeutic approaches that harness both targeted and immunotherapeutic strategies may offer significant additional benefits.

In conclusion, therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR show immense promise in oncology. The current landscape is robust, with multiple approved agents that have transformed the treatment paradigm for cancers such as NSCLC and colorectal cancer. Emerging therapies, designed to overcome resistance and improve specificity, are now entering clinical trials and are supported by detailed molecular, pharmacokinetic, and clinical efficacy data. Despite challenges associated with resistance and adverse effects, the future of EGFR-targeted therapy appears bright. Ongoing research and innovative clinical trial designs are poised to refine these strategies further, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for patients across a broad range of EGFR-driven diseases.

EGFR Function and Significance

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a central role in regulating cell survival, growth, differentiation, and migration. This receptor is involved in transmitting signals from its extracellular ligands—such as epidermal growth factor (EGF)—into intracellular signaling cascades such as the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. EGFR activation triggers phosphorylation events on its cytoplasmic tail that allow binding of adaptor proteins and thus modulate gene expression, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis. Consequently, EGFR is not only essential for normal cellular functions but is also critical in developmental processes and tissue homeostasis. Its ability to maintain cellular functions underlies the interest in targeting EGFR in situations where its signaling becomes deregulated.

Role of EGFR in Disease Pathogenesis

Aberrant EGFR signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous cancers and other diseases. Overexpression of the EGFR protein is detected in many solid tumors—such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), colorectal cancer, and glioblastoma—as well as in some inflammatory and other non-neoplastic conditions. EGFR mutations, gene amplification, or splice variants (like EGFRvIII) lead to constitutive activation that drives uncontrolled cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Such aberrations often result in aggressive tumor behavior, poorer prognosis, and resistance to conventional therapies. This clear involvement of EGFR in cancer progression makes the receptor a prime target for therapeutic intervention.

Therapeutic Candidates Targeting EGFR

Current Approved Therapies

Over the past two decades, several therapeutic candidates that directly target EGFR have been approved across multiple indications.

• Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are the earliest and most established class of EGFR therapies. Agents such as cetuximab and panitumumab bind to the extracellular domain of EGFR, preventing ligand binding and receptor dimerization. Cetuximab, in particular, was one of the first anti-EGFR antibodies approved and has been used in colorectal cancer and head and neck cancers. Panitumumab, a fully human mAb, is also approved predominantly in metastatic colorectal cancer for patients with wild-type RAS tumors.

• Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) represent another class of approved EGFR-targeting drugs. Examples include erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, and dacomitinib. These agents are orally bioavailable and work by binding to the ATP binding site of the EGFR intracellular kinase domain, hence blocking receptor autophosphorylation and downstream signaling. They have been extensively used in NSCLC patients harboring EGFR mutations.

• Other formulations include antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) that utilize the specificity of mAbs coupled with potent cytotoxic payloads. Although these are at an earlier stage of approval compared with mAbs and TKIs, some ADCs are available for clinical use and are continuously being evaluated.

These therapies have been incorporated into clinical practice with established dosing guidelines and robust supporting clinical trial results. Their approval has been based on demonstrated improvements in progression-free survival, overall response rates, and quality‐of‐life measures across selected cancer subtypes.

Emerging Therapeutic Candidates

Alongside the established therapies, several emerging candidates are now under clinical evaluation or in preclinical development. These candidates aim to address some of the limitations found in the current approved therapies.

• Next-generation EGFR TKIs such as osimertinib have been developed to overcome resistance mutations (for example, the T790M mutation) that arise after initial treatment with first-generation EGFR inhibitors. Osimertinib is notable for its ability to target both sensitizing and resistant EGFR mutations and is now approved for second-line therapy in NSCLC. Its clinical development is supported by strong pharmacodynamic data and robust clinical trial outcomes.

• Irreversible inhibitors and multi-target inhibitors are also being developed. These drugs bind covalently to the EGFR kinase domain and have mechanisms to block multiple members of the EGFR family simultaneously. Such agents—including combinations of EGFR-TKIs with HER2 inhibitory properties (dual inhibitors) or inhibitors with broader spectrum activity—are currently being evaluated in phase II and III clinical trials. Their development is driven by the need to delay or overcome acquired resistance that frequently limits the effectiveness of reversible inhibitors.

• Bispecific antibodies and engineered antibody fragments (such as nanobodies or single-chain variable fragments, scFv) are being explored as alternatives to full-size mAbs. These engineered constructs are smaller in size, potentially allowing greater tissue penetration and faster clearance. Their ability to target two independent epitopes simultaneously (often on EGFR or both EGFR and another relevant receptor such as HER2) may lead to an enhanced anti-tumor response while reducing immunogenicity and adverse events.

• Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) continue to be optimized. Novel conjugation strategies, improved linker technologies, and optimized payloads are in development to overcome the limitations of off-target toxicity seen with earlier ADCs. These improved ADCs enhance the delivery of cytotoxic agents specifically to EGFR-overexpressing tumors while sparing normal tissue, potentially leading to improved therapeutic indices.

• In addition to direct EGFR inhibitors, agents targeting downstream or parallel pathways are being developed as combination therapies to overcome resistance. For example, combining EGFR inhibitors with PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors or anti-angiogenic agents (such as bevacizumab) is under investigation. Such combination therapies may block compensatory pathways that allow tumors to evade the effects of single-agent EGFR inhibition.

Mechanism of Action

How Therapies Target EGFR

Therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR work via various molecular strategies to inhibit receptor activation and downstream signaling.

• Monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab bind to the extracellular domain of EGFR to block the binding of natural ligands like EGF and transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α). This action prevents receptor dimerization—a necessary step for receptor activation—and subsequent autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues. In addition, such antibodies can induce receptor internalization and degradation and may also stimulate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), thereby enlisting the immune system to target tumor cells.

• Small molecule TKIs like erlotinib, gefitinib, and afatinib are designed to compete with ATP for binding at the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR. By doing so, they inhibit its autophosphorylation and the activation of downstream signaling cascades including the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways. These inhibitors vary based on whether they are reversible or irreversible. For example, first-generation TKIs bind reversibly, whereas later-generation compounds such as osimertinib bind irreversibly, accounting for their increased potency against certain resistance mutations.

• Bispecific antibodies and engineered smaller antibody fragments operate by simultaneously engaging distinct epitopes and potentially blocking multiple receptor interactions at once. This approach may result in more complete inhibition of EGFR signaling either by blocking ligand binding and receptor dimerization more efficiently or by reducing tumor cell resistance through downregulation of EGFR protein levels.

Differences in Mechanism Among Candidates

Despite targeting the same receptor, the therapeutic candidates differ markedly in their mechanism of action, pharmacodynamics, and clinical application.

• The difference between mAbs and TKIs is fundamental. mAbs target the extracellular region and generally lead to receptor downregulation and ADCC, while TKIs work intracellularly to prevent kinase activity. These differences manifest in the pharmacokinetic profiles – mAbs are typically infused with a long half-life while TKIs are orally administered with shorter half-lives.

• Among TKIs, reversible inhibitors (like erlotinib and gefitinib) cause transient inhibition of EGFR kinase activity, whereas irreversible inhibitors (such as osimertinib and dacomitinib) form a covalent bond with EGFR, leading to longer-lasting effects. This irreversible binding is especially beneficial for targeting resistant mutations that may otherwise allow for receptor reactivation in the presence of reversible inhibition.

• Engineered antibody fragments and bispecific constructs provide advantages in terms of tumor penetration and clearance. Their reduced molecular size and the ability to target two separate epitopes enable them to overcome some of the dosing and biodistribution challenges seen with conventional monoclonal antibodies.

• Combination therapeutics further differentiate themselves by addressing compensatory mechanisms that single agents may not cover. For example, while EGFR inhibitors block the primary signaling pathway, combinations that include inhibitors of the downstream PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and angiogenesis inhibitors broaden the blockade to secondary escape routes used by tumors, thus potentially producing a more robust and durable clinical response.

Clinical Trials and Efficacy

Overview of Key Clinical Trials

Extensive clinical trial programs have validated both the approved and emerging EGFR-targeting candidates in various cancer types.

• Early phase trials for cetuximab and gefitinib demonstrated objective tumor regression and improvements in progression-free survival for patients with EGFR-driven tumors, leading to their subsequent approval. Key trials in NSCLC and colorectal cancer established response rates and survival benefits that supported the broader clinical adoption of these agents.

• Subsequent trials with next-generation inhibitors, such as osimertinib, have focused on overcoming resistance. For instance, the clinical trial programs for osimertinib demonstrated efficacy in patients with acquired T790M mutations after failure of first-generation TKIs, with improved progression-free survival and tolerable safety profiles.

• Moreover, clinical studies examining combination regimens—such as the addition of bevacizumab (an anti-VEGF antibody) to EGFR inhibitors—have produced mixed but promising results with enhanced efficacy in some patient subgroups. Trials investigating bispecific antibodies and ADCs are ongoing and are designed to optimize dosing while reducing toxicity.

• Other studies are addressing the role of engineered antibody fragments and the use of liquid biopsies to monitor treatment resistance and adapt therapeutic strategies accordingly. These trials contribute essential data on the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and immune-mediated effects of the novel agents under development.

Efficacy and Safety Profiles

Clinical trial data reveal that the efficacy and safety of EGFR-targeting therapies can vary greatly based on patient genetics, tumor type, and treatment regimen.

• Approved mAbs offer substantial benefits in patients with EGFR-overexpressing tumors. For example, cetuximab has provided significant improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival in colorectal cancer patients with wild-type KRAS. However, as with many antibody-based therapies, infusion-related reactions and skin toxicities are common adverse events.

• TKIs are generally well tolerated in patients with NSCLC. Erlotinib and gefitinib have shown robust responses in patients with activating EGFR mutations, predominantly in adenocarcinoma histologies and among non-smokers. Their common adverse effects include rash and diarrhea but these are usually manageable. Next-generation TKIs like osimertinib have improved safety profiles due to greater specificity for mutant EGFR and lower off-target activity. The irreversible binding nature of these inhibitors leads to sustained receptor inhibition and is associated with higher rates of response in resistant populations.

• Emerging candidates such as bispecific antibodies and ADCs are still undergoing rigorous evaluation. Early-phase studies suggest that these agents may combine high antitumor efficacy with reduced systemic toxicity owing to the targeted delivery of cytotoxins. However, further trials are needed to confirm long-term safety and to optimize delivery parameters, as immunogenicity and off-target effects remain potential concerns.

• Combination therapies, which include dual inhibition strategies addressing compensatory pathways, have shown potential for better clinical outcomes in patients with refractory disease. Combined EGFR and VEGF inhibitors, for instance, may enhance tumor control but also exhibit additive toxicities that require careful management.

Challenges and Future Directions

Resistance and Limitations

Despite the success of EGFR-targeted approaches, several challenges and mechanisms of resistance continue to hinder long-term efficacy.

• Intrinsic and acquired resistance are major obstacles. Common mechanisms include secondary mutations in the EGFR kinase domain (such as T790M), activation of alternate signaling pathways (including MET amplification, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway activation), and phenotypic changes including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). These resistance mechanisms reduce the effectiveness of both mAbs and TKIs over time and necessitate the development of next-generation inhibitors.

• Drug tolerance emerges from heterogeneous tumor cell populations. Variation in EGFR expression, receptor dimerization states, and interactions with other membrane receptors (e.g., HER2) further contribute to resistance. In many cases, even after a period of effective therapy, the tumor may evolve multiple bypass tracks that allow continued growth.

• Safety issues, such as skin rash, gastrointestinal disturbances, and, in some cases, cardiotoxicity (notably observed with HER2-directed agents that share pathways with EGFR inhibitors), are additional limitations in the clinical use of these drugs. Adverse effects must be balanced against clinical benefits, particularly in combination regimens.

• Furthermore, inter-patient variability based on genetic markers (such as EGFR mutation status and copy number), ethnic differences, and prior treatment history present challenges in choosing the ideal therapy and dosing regimens. The absence of robust predictive biomarkers that can definitively stratify patients for maximum benefit remains a significant gap in personalized medicine.

Future Research and Development

Research continues to drive the evolution of EGFR-targeting strategies in several directions.

• Development efforts are focused on next-generation TKIs that not only target the common sensitivity mutations but also have activity against resistant variants. New compounds are being designed using structure-based drug design and molecular modeling, which allows for the identification of novel binding pockets and allosteric sites on the EGFR kinase domain. These efforts aim to produce inhibitors with enhanced potency, selectivity, and a lower propensity for resistance.

• Combination therapies are under active investigation to overcome compensatory resistance mechanisms. Trials combining EGFR inhibitors with agents that inhibit signaling pathways downstream (such as PI3K, Akt, or mTOR inhibitors) or parallel pathways (such as MET inhibitors or anti-angiogenic agents like bevacizumab) are underway. The goal is to achieve a more comprehensive blockade of cellular signaling that circumvents multiple resistance routes.

• Efforts are also being made to develop bispecific antibodies capable of engaging not only EGFR but also other related receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., HER2). These agents promise to overcome receptor heterogeneity and co-activation that often contribute to drug resistance. Engineering of these antibodies to optimize tumor penetration and to reduce immunogenicity is a high priority in the field.

• In addition, newer antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) with improved drug-to-antibody ratios, more stable linkers, and more potent cytotoxic agents are being explored. These ADCs are designed to deliver high concentrations of chemotherapy selectively to EGFR-positive tumor cells, sparing normal tissues and reducing systemic toxicity.

• Biomarker development, including the use of liquid biopsies and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), is emerging as a promising tool to monitor therapeutic responses and the evolution of resistance mechanisms. This will enable dynamic adjustment of therapy and may facilitate the earlier identification of resistance, allowing clinicians to switch therapies or initiate combination regimens promptly.

• Nanotechnology and novel delivery systems are also being investigated. These approaches may increase drug concentration at the tumor site while reducing off-target exposure and adverse effects. For example, nanoparticle-based delivery of EGFR inhibitors or ADCs may enhance penetration into solid tumors and improve therapeutic outcomes.

• Moreover, ongoing research is addressing the modulation of the immune microenvironment in combination with EGFR-targeted therapies. Emerging evidence suggests that immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with EGFR inhibitors may lead to synergistic effects, particularly in tumors expressing high levels of EGFR. Understanding the interplay between EGFR signaling and immune response is an area of active investigation that may yield novel combination strategies.

• Finally, resistance mechanisms associated with non-genomic changes, such as epigenetic modifications and microRNA regulation, are increasingly recognized as important factors in therapeutic failure. Future developments may include epigenetic modifiers combined with EGFR-targeting agents to re-sensitize tumors to treatment. These multimodal approaches have the potential to provide a more durable response by targeting both the genomic and non-genomic drivers of resistance.

Conclusion

In summary, the therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR encompass a broad spectrum of molecular agents that range from fully approved monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab, panitumumab) and small molecule TKIs (erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, dacomitinib) to emerging agents such as next-generation inhibitors (osimertinib), bispecific antibodies, ADCs, and engineered antibody fragments. Each candidate targets EGFR through distinct yet sometimes overlapping mechanisms. Monoclonal antibodies intercept ligand binding and promote receptor internalization and immune-mediated killing, whereas TKIs competitively inhibit the ATP-binding site, thereby blocking intracellular signaling cascades. Researchers have also innovated in the realm of nanotechnology and combined modality therapies to thwart the common challenge of drug resistance and achieve more targeted delivery with fewer side effects.

Clinical trials spanning early phase to pivotal registrational studies have provided robust data on the efficacy and safety profiles of these agents. They highlight improvements in progression-free survival, overall responses, and in select patient populations, overall survival benefits. The accumulated evidence demonstrates that while the first-generation EGFR inhibitors are effective in certain genomic contexts, acquired resistance remains a critical challenge. To address this, combination therapies targeting parallel pathways (for example, VEGF or PI3K/Akt/mTOR) or employing next-generation irreversible inhibitors are being actively developed and show promising results.

Nevertheless, despite these advances, the continued evolution of resistance—through mechanisms such as secondary mutations, bypass signaling, and EMT—necessitates further research. Future studies directed toward innovative inhibitor designs, optimized combination regimens, and the integration of advanced biomarker strategies (including ctDNA monitoring) will likely improve patient selection and provide more durable responses. Moreover, as our understanding of the interplay between EGFR signaling and the tumor microenvironment advances, novel therapeutic approaches that harness both targeted and immunotherapeutic strategies may offer significant additional benefits.

In conclusion, therapeutic candidates targeting EGFR show immense promise in oncology. The current landscape is robust, with multiple approved agents that have transformed the treatment paradigm for cancers such as NSCLC and colorectal cancer. Emerging therapies, designed to overcome resistance and improve specificity, are now entering clinical trials and are supported by detailed molecular, pharmacokinetic, and clinical efficacy data. Despite challenges associated with resistance and adverse effects, the future of EGFR-targeted therapy appears bright. Ongoing research and innovative clinical trial designs are poised to refine these strategies further, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for patients across a broad range of EGFR-driven diseases.

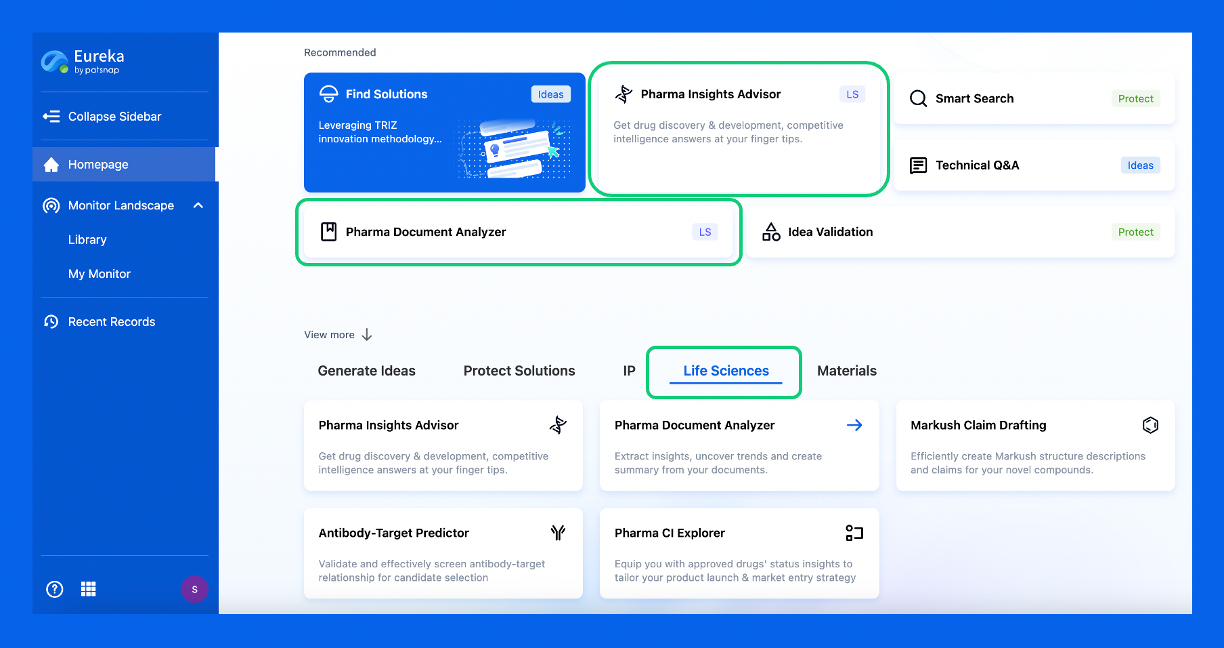

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.