Request Demo

What is the significance of a placebo in clinical research?

21 March 2025

Introduction to Placebos

Placebos have long played a central role in clinical research, serving as both a methodological tool and a subject of ethical scrutiny. In broad terms, a placebo is an intervention devoid of specific active components intended to treat a condition, yet it can nonetheless invoke a variety of psychological and physiological responses. In clinical research, the significance of a placebo extends from its historical usage as a comparator in randomized controlled trials to its modern applications in harnessing non‐specific treatment effects that can influence patient outcomes. This discussion will provide a comprehensive answer on the significance of a placebo in clinical research, following a general‐specific‐general format that examines definitions, roles, ethical issues, impacts on outcomes, and future directions.

Definition and Historical Background

The concept of a placebo originated from the Latin word “placere,” meaning “to please”. Historically, placebos were first introduced as treatments that were believed to have only a symbolic effect rather than any therapeutic benefit. In the early days of medicine, until the mid‐20th century, placebos were routinely employed as “sugar pills” or inert substances that physicians administered with the notion that they might evoke a positive psychological response, sometimes simply to fulfill patient expectations. The evolution of the placebo concept is closely intertwined with the development of the controlled experimental methodology in clinical research, particularly following World War II when the concept of the randomized controlled trial (RCT) became established. Over the years, our understanding of the placebo has shifted significantly—from viewing it as an inert substance to recognizing it as a phenomenon with measurable psychobiological effects that can alter clinical outcomes via complex mechanisms.

In addition to the inert substance definition, several historical accounts have revealed that the context of the treatment—the patient’s expectation, conditioning, and the manner of the provider’s communication—plays an integral role in mediating the placebo effect. As early as the 18th century, placebos were used to appease patients, and by the mid‐20th century, standardized placebo‐controlled RCTs emerged as the gold standard to distinguish specific effects of an intervention from these non‐specific responses. The significance of these historical milestones is that they laid the foundation for the modern systematic investigation of placebo effects and highlighted the need to control for nonspecific variables in clinical research.

Types of Placebos

Placebos can be classified primarily into “pure” and “impure” types. A pure placebo is an inert substance or treatment that contains no active pharmacological ingredient; common examples include sugar pills or saline injections. Conversely, an impure placebo may contain an active substance, but it is administered in a clinical context for which it is not specifically indicated (for instance, prescribing antibiotics for a viral infection). The distinction is important because even impure placebos can produce a measurable clinical response depending on factors such as patient expectation and the therapeutic context. Furthermore, modern research has expanded the classification of placebos to include “open‐label” placebos, in which patients are transparently told that they are receiving an inert substance. Intriguingly, even when patients are aware that they are receiving a placebo, beneficial effects have been observed, thereby challenging the traditional view that deception is necessary for a placebo response.

Role of Placebos in Clinical Research

Placebos occupy a pivotal role in clinical research. Their primary significance lies in the ability to serve as control interventions in clinical trials, thereby enabling the separation of a drug’s or intervention’s specific effects from non‐specific effects that arise from patient expectations, the therapeutic ritual, and other psychological factors. Their role is twofold: as a methodological tool to reduce bias and isolate a treatment’s true efficacy, and as a phenomenon of interest in its own right due to the measurable placebo effect.

Control Groups and Bias Reduction

The use of a placebo as a control in clinical trials is fundamental for minimizing bias. By randomly assigning participants to receive either the active treatment or a placebo, researchers can more rigorously compare the differential outcomes that are directly attributable to the treatment’s pharmacological efficacy, independent of any psychological or contextual influences. Randomization and blinding—the double-blind design specifically where neither the participant nor the investigator knows which treatment the participant is receiving—help ensure that the placebo group accounts for effects related to natural disease progression, the spontaneous improvement of symptoms, and the influence of patient perceptions. This, in turn, establishes an assay sensitivity—the ability of a trial to accurately demonstrate a treatment effect—thereby providing robust evidence for or against therapeutic efficacy.

Moreover, the integration of placebo controls helps reduce potentially misleading biases in data interpretation. For instance, without a placebo group, improvements observed in an intervention arm could be mistakenly ascribed solely to the intervention itself, whereas they might partly or entirely be due to natural variability or the patient’s mental state. Such control groups are, therefore, not only essential to the design of rigorous RCTs, but also to the credibility of the results derived from these trials. This methodological framework underscores the significance of placebo-controlled trial design as it helps clarify the net benefit of any therapeutic intervention over and above the placebo response.

Placebo Effect and Patient Outcomes

Beyond its utilitarian role in controlling for bias, the placebo effect is itself a phenomenon that can influence patient outcomes. The placebo effect comprises a suite of psychobiological mechanisms—such as patient expectations, classical conditioning, and the therapeutic alliance—that can lead to real, measurable improvements in symptoms. Research has demonstrated that the administration of a placebo can lead to the activation of endogenous opioid pathways, as well as other neuromodulatory systems such as dopamine, which mediate pain relief and mood improvements. For example, studies have shown that placebo analgesia can be reversed by opioid antagonists, confirming the existence of a genuine physiological process underlying this effect.

Patient outcomes in trials are therefore not only determined by the specific pharmacological actions of a treatment but also by the nonspecific effects generated by the patient’s expectations and the overall treatment context. Such effects have been observed across various clinical conditions including pain management, depression, and migraine, where the placebo response can account for a significant portion of the therapeutic improvement. The recognition that placebos can induce real physiological and psychological benefits is influential in informing both clinical trial design and clinical practice, particularly as researchers seek to harness these effects to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

The use of placebos—especially in clinical practice—raises numerous ethical questions. These issues center on the principles of patient autonomy, informed consent, and the obligation to do no harm. Historically, the use of deceptive placebos in both clinical trials and clinical practice has been fraught with ethical challenges. However, recent research into open-label placebos, where patients are informed of the inert nature of the treatment, offers compelling evidence that ethical concerns may be mitigated without compromising the potential therapeutic benefit.

Ethical Guidelines for Placebo Use

Various ethical guidelines and statements, such as the Declaration of Helsinki, indicate that placebos should be used only under circumstances where withholding standard treatment does not subject patients to additional harm. These guidelines emphasize that the use of a placebo is justified in research only when no proven effective intervention exists or when the significant methodological advantages of using a placebo outweigh the risks to participants. In practice, this means that in clinical research, participants must be fully informed of the possibility of receiving a placebo and that the placebo intervention should not expose them to undue risk. Recent policy shifts advocate for transparency, as shown in studies on open-label placebos which demonstrate that disclosure does not necessarily nullify the beneficial placebo effects.

Moreover, ethical usage is extended to clinical practice on the basis that physicians can harness placebo effects ethically. This approach requires that placebos are not used to deceive patients but instead may be incorporated as adjuncts to conventional treatments under an informed consent framework. For instance, some scholars propose that incorporating placebo interventions without deception can be morally permissible – and in some cases even ethically imperative – when they contribute to therapeutic benefit. The literature thus suggests that the integration of placebos in clinical research and care should be guided by clear ethical guidelines ensuring that patient autonomy remains paramount while simultaneously optimizing health outcomes.

Controversies and Debates

Notwithstanding these guidelines, significant controversies continue to surround the use of placebos. Critics argue that the use of deceptive placebos—even in controlled research settings—violates the principle of informed consent and risks undermining patient trust. This debate is fueled by the fact that many patients, when informed that their treatment may be a placebo, could feel misled or less hopeful, potentially compromising the integrity of the therapeutic alliance. On the other side of the debate, proponents maintain that the placebo effect frequently contributes to positive clinical outcomes and that harnessing these benefits can be ethically justified if patients are adequately informed about the treatment rationale.

These controversies extend into the methodological realm as well. Some researchers have argued that the over-reliance on placebo controls could lead to underestimation of the true effects of active treatments when the placebo effect is unexpectedly potent. Moreover, the stratification of participants based on their likelihood to respond to placebo—a concept that has even been subject to patenting to optimize clinical trial designs—raises questions regarding the fairness and transparency of patient selection processes. Thus, the ethical debates not only encompass individual patient rights but also large-scale research practices and the need for reforms in research methodologies to minimize any adverse consequences of adult placebo use.

Impact on Research Outcomes

The role of the placebo extends far beyond the control group in clinical trials. The presence of a placebo group serves multiple purposes that directly affect the interpretation of research outcomes, the reliability of clinical conclusions, and the statistical significance of trial results.

Case Studies Demonstrating Placebo Impact

Numerous clinical trials have documented the tangible impact of the placebo effect on patient outcomes. For instance, in pain-related studies, patients receiving placebos have demonstrated clinically significant improvements in pain scores, sometimes approaching the efficacy of actual pharmacological interventions. Case studies in migraine treatment have shown that placebo responses can be as high as 30% to 50% when measured by subjective outcomes such as pain relief and symptom improvement. Similarly, research into the placebo effect in depression trials has repeatedly highlighted that improvements in mood and overall quality of life may occur even when patients receive a placebo treatment.

Furthermore, case studies from neuromodulation and neurology have demonstrated that the expectation-induced placebo effect can lead to observable changes in brain activity as measured by imaging studies. For example, in Parkinson’s disease, the administration of a placebo resulted in increased dopaminergic activation in the striatum, correlating with significant improvements in motor function. Such examples reinforce the notion that placebos are not inert bystander interventions but exert measurable clinical benefits through complex neurobiological pathways. These case studies, drawn from diverse fields ranging from pain management to neurology, underscore the multifaceted impact of the placebo effect on research outcomes.

Statistical Significance and Data Interpretation

In randomized controlled trials, statistical comparisons between the active treatment and the placebo are critical for evaluating drug efficacy and safety. The effect size measured in the active treatment group is often interpreted against the backdrop of the placebo response. As described in meta-analyses, when both the treatment and placebo groups demonstrate significant improvements, it is essential to employ sophisticated statistical techniques to dissect the specific treatment effect from the placebo effect.

Researchers often use methodologies that compare test statistics derived from both the treatment and placebo arms to evaluate whether the observed differences are statistically significant. In some cases, the use of placebo actions has even been integrated into advanced methods to assess statistical significance by comparing a desired action to a battery of placebo actions. This approach not only enhances the credibility of the findings but also minimizes the risk of false positive results that might arise from regression toward the mean. By aiding in robust data interpretation, placebos thereby contribute to improved assay sensitivity in clinical trials.

The analysis of placebo responses has also become a critical factor in refining clinical trial designs and in adjusting for non-specific effects that might otherwise confound the interpretation of efficacy. Through the incorporation of placebo data, researchers can better account for patient-specific factors such as expectation, natural disease progression, and spontaneous remission. Consequently, this enables a more accurate estimation of the true pharmacological effect, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the clinical trial outcomes.

Future Perspectives

As our understanding of the placebo effect continues to evolve, so too do the methods and applications of placebo use in clinical research. Future research directions are geared toward refining the role of placebos, reducing ethical concerns, and enhancing the therapeutic potential of non-specific effects through innovative methodological approaches.

Innovations in Placebo Use

Recent years have seen a significant shift in how placebos are conceptualized and utilized, particularly with the advent of open-label placebo trials. Unlike traditional placebo interventions that rely on deception, open-label placebos are administered transparently, with patients being informed that they are receiving an inert substance. Remarkably, studies have found that open-label placebos can still produce clinically significant improvements in conditions such as chronic pain, depression, and irritable bowel syndrome. This innovation challenges the conventional paradigm that deception is essential for eliciting a placebo response, and it opens up new avenues for ethically acceptable placebo use in clinical practice.

Another promising development is the integration of placebo response profiling into clinical trial designs. Several patents now focus on methods and systems for predicting or even eliminating placebo responders from clinical trials to optimize data analysis. The use of biomarkers and computational techniques to assess a subject’s likelihood of exhibiting a placebo response represents a cutting-edge approach that may enhance the precision of clinical trials and ultimately lead to more targeted therapeutic strategies. Moreover, system-oriented approaches, such as those used in protocol development involving crowdsourced feedback from diverse stakeholders, illustrate the potential for leveraging collective intelligence to refine placebo-controlled trial methodologies.

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite these innovations, several challenges remain in harnessing the full potential of placebo effects in clinical research. A key challenge is maintaining the delicate balance between methodological rigor and ethical considerations—especially when the use of placebos might compromise informed consent or patient trust. There is an ongoing need to enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the placebo effect, which involve a complex interplay of psychological, neurobiological, and social factors. Future research should focus on elucidating these pathways in greater detail, as well as determining the conditions under which placebo interventions can be ethically integrated into both clinical trials and routine clinical practice.

Another significant challenge lies in the heterogeneity of placebo responses among participants. Individual differences such as personality traits, prior treatment experiences, and genetic factors can substantially influence the magnitude and quality of the placebo effect. Addressing this variability requires the development of predictive models and the potential stratification of clinical trial participants based on their likelihood to respond to placebo interventions. Advances in machine learning and bioinformatics are poised to play a major role in achieving such stratification, which ultimately would lead to more personalized approaches in clinical therapeutics.

Furthermore, there is a need for consensus regarding what constitutes a clinically meaningful placebo response. While some studies indicate significant improvements in subjective outcomes, such as pain and mood, other studies have found limited objective benefits. Bridging this gap is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic impact of placebo mechanisms. Future research efforts must therefore integrate objective biomarkers with subjective reports to provide a holistic picture of the placebo response.

Lastly, research must address regulatory and practical issues associated with placebo use. Standardizing outcome measures, improving statistical analyses, and ensuring that ethical guidelines are uniformly applied across diverse research settings are critical steps needed to enhance the validity of placebo-controlled trials. Collaborative efforts among regulatory bodies, research institutions, and industry stakeholders will be crucial in overcoming these challenges and advancing the field.

Conclusion

In summary, the significance of the placebo in clinical research is multifaceted and profound. Historically, placebos have evolved from being viewed simply as inert “sugar pills” to being recognized as powerful phenomena capable of eliciting real neurobiological and psychobiological responses. They not only serve as essential control tools that help reduce bias and isolate the specific effects of therapeutic interventions, but they also contribute directly to patient outcomes through complex mechanisms such as expectation, conditioning, and the therapeutic alliance. Ethically, the use of placebos has been and continues to be a topic of vigorous debate, particularly regarding issues of deception and informed consent. Innovations, such as open-label placebos and methods for predicting placebo responsiveness, are paving the way for a future in which the placebo effect can be ethically integrated into clinical practice and research, thereby enhancing treatment outcomes and optimizing clinical trial design.

From a methodological perspective, placebo controls ensure robust comparisons in RCTs and help researchers disentangle the pharmacological effects of an intervention from the non-specific effects attributable to the patient-clinician relationship and individual expectations. Statistically, the incorporation of placebo data is vital for accurately interpreting treatment effects, reducing confounding influences, and enhancing assay sensitivity. Ethically, recent progress in open-label placebo studies has revolutionized our understanding of how non-deceptive placebo interventions might be used to achieve therapeutic benefits while upholding patient autonomy.

Looking to the future, embracing innovations in placebo research—including predictive modeling of placebo responsiveness and the integration of extensive patient feedback in clinical protocol development—is essential for advancing the field. While challenges remain, particularly concerning the heterogeneity of placebo responses and ethical debates regarding informed consent, future research promises to refine our understanding and application of placebo effects. This will not only improve data interpretation in clinical trials but may also lead to novel therapeutic strategies that harness the body’s inherent healing mechanisms.

In conclusion, placebos hold significant value in clinical research by providing a rigorous means to control for non-specific effects, enhancing our understanding of human physiology and psychology, and offering potential therapeutic benefits when used ethically and transparently. The continuous evolution of placebo research—from traditional blinded trials to innovative open-label studies and predictive assessments—emphasizes the enduring importance of the placebo both as a scientific tool and as a phenomenon worthy of further study. It is imperative that future research continues to address the methodological, ethical, and practical challenges associated with placebo use to fully harness its potential for improving patient outcomes and advancing medicine.

Placebos have long played a central role in clinical research, serving as both a methodological tool and a subject of ethical scrutiny. In broad terms, a placebo is an intervention devoid of specific active components intended to treat a condition, yet it can nonetheless invoke a variety of psychological and physiological responses. In clinical research, the significance of a placebo extends from its historical usage as a comparator in randomized controlled trials to its modern applications in harnessing non‐specific treatment effects that can influence patient outcomes. This discussion will provide a comprehensive answer on the significance of a placebo in clinical research, following a general‐specific‐general format that examines definitions, roles, ethical issues, impacts on outcomes, and future directions.

Definition and Historical Background

The concept of a placebo originated from the Latin word “placere,” meaning “to please”. Historically, placebos were first introduced as treatments that were believed to have only a symbolic effect rather than any therapeutic benefit. In the early days of medicine, until the mid‐20th century, placebos were routinely employed as “sugar pills” or inert substances that physicians administered with the notion that they might evoke a positive psychological response, sometimes simply to fulfill patient expectations. The evolution of the placebo concept is closely intertwined with the development of the controlled experimental methodology in clinical research, particularly following World War II when the concept of the randomized controlled trial (RCT) became established. Over the years, our understanding of the placebo has shifted significantly—from viewing it as an inert substance to recognizing it as a phenomenon with measurable psychobiological effects that can alter clinical outcomes via complex mechanisms.

In addition to the inert substance definition, several historical accounts have revealed that the context of the treatment—the patient’s expectation, conditioning, and the manner of the provider’s communication—plays an integral role in mediating the placebo effect. As early as the 18th century, placebos were used to appease patients, and by the mid‐20th century, standardized placebo‐controlled RCTs emerged as the gold standard to distinguish specific effects of an intervention from these non‐specific responses. The significance of these historical milestones is that they laid the foundation for the modern systematic investigation of placebo effects and highlighted the need to control for nonspecific variables in clinical research.

Types of Placebos

Placebos can be classified primarily into “pure” and “impure” types. A pure placebo is an inert substance or treatment that contains no active pharmacological ingredient; common examples include sugar pills or saline injections. Conversely, an impure placebo may contain an active substance, but it is administered in a clinical context for which it is not specifically indicated (for instance, prescribing antibiotics for a viral infection). The distinction is important because even impure placebos can produce a measurable clinical response depending on factors such as patient expectation and the therapeutic context. Furthermore, modern research has expanded the classification of placebos to include “open‐label” placebos, in which patients are transparently told that they are receiving an inert substance. Intriguingly, even when patients are aware that they are receiving a placebo, beneficial effects have been observed, thereby challenging the traditional view that deception is necessary for a placebo response.

Role of Placebos in Clinical Research

Placebos occupy a pivotal role in clinical research. Their primary significance lies in the ability to serve as control interventions in clinical trials, thereby enabling the separation of a drug’s or intervention’s specific effects from non‐specific effects that arise from patient expectations, the therapeutic ritual, and other psychological factors. Their role is twofold: as a methodological tool to reduce bias and isolate a treatment’s true efficacy, and as a phenomenon of interest in its own right due to the measurable placebo effect.

Control Groups and Bias Reduction

The use of a placebo as a control in clinical trials is fundamental for minimizing bias. By randomly assigning participants to receive either the active treatment or a placebo, researchers can more rigorously compare the differential outcomes that are directly attributable to the treatment’s pharmacological efficacy, independent of any psychological or contextual influences. Randomization and blinding—the double-blind design specifically where neither the participant nor the investigator knows which treatment the participant is receiving—help ensure that the placebo group accounts for effects related to natural disease progression, the spontaneous improvement of symptoms, and the influence of patient perceptions. This, in turn, establishes an assay sensitivity—the ability of a trial to accurately demonstrate a treatment effect—thereby providing robust evidence for or against therapeutic efficacy.

Moreover, the integration of placebo controls helps reduce potentially misleading biases in data interpretation. For instance, without a placebo group, improvements observed in an intervention arm could be mistakenly ascribed solely to the intervention itself, whereas they might partly or entirely be due to natural variability or the patient’s mental state. Such control groups are, therefore, not only essential to the design of rigorous RCTs, but also to the credibility of the results derived from these trials. This methodological framework underscores the significance of placebo-controlled trial design as it helps clarify the net benefit of any therapeutic intervention over and above the placebo response.

Placebo Effect and Patient Outcomes

Beyond its utilitarian role in controlling for bias, the placebo effect is itself a phenomenon that can influence patient outcomes. The placebo effect comprises a suite of psychobiological mechanisms—such as patient expectations, classical conditioning, and the therapeutic alliance—that can lead to real, measurable improvements in symptoms. Research has demonstrated that the administration of a placebo can lead to the activation of endogenous opioid pathways, as well as other neuromodulatory systems such as dopamine, which mediate pain relief and mood improvements. For example, studies have shown that placebo analgesia can be reversed by opioid antagonists, confirming the existence of a genuine physiological process underlying this effect.

Patient outcomes in trials are therefore not only determined by the specific pharmacological actions of a treatment but also by the nonspecific effects generated by the patient’s expectations and the overall treatment context. Such effects have been observed across various clinical conditions including pain management, depression, and migraine, where the placebo response can account for a significant portion of the therapeutic improvement. The recognition that placebos can induce real physiological and psychological benefits is influential in informing both clinical trial design and clinical practice, particularly as researchers seek to harness these effects to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

The use of placebos—especially in clinical practice—raises numerous ethical questions. These issues center on the principles of patient autonomy, informed consent, and the obligation to do no harm. Historically, the use of deceptive placebos in both clinical trials and clinical practice has been fraught with ethical challenges. However, recent research into open-label placebos, where patients are informed of the inert nature of the treatment, offers compelling evidence that ethical concerns may be mitigated without compromising the potential therapeutic benefit.

Ethical Guidelines for Placebo Use

Various ethical guidelines and statements, such as the Declaration of Helsinki, indicate that placebos should be used only under circumstances where withholding standard treatment does not subject patients to additional harm. These guidelines emphasize that the use of a placebo is justified in research only when no proven effective intervention exists or when the significant methodological advantages of using a placebo outweigh the risks to participants. In practice, this means that in clinical research, participants must be fully informed of the possibility of receiving a placebo and that the placebo intervention should not expose them to undue risk. Recent policy shifts advocate for transparency, as shown in studies on open-label placebos which demonstrate that disclosure does not necessarily nullify the beneficial placebo effects.

Moreover, ethical usage is extended to clinical practice on the basis that physicians can harness placebo effects ethically. This approach requires that placebos are not used to deceive patients but instead may be incorporated as adjuncts to conventional treatments under an informed consent framework. For instance, some scholars propose that incorporating placebo interventions without deception can be morally permissible – and in some cases even ethically imperative – when they contribute to therapeutic benefit. The literature thus suggests that the integration of placebos in clinical research and care should be guided by clear ethical guidelines ensuring that patient autonomy remains paramount while simultaneously optimizing health outcomes.

Controversies and Debates

Notwithstanding these guidelines, significant controversies continue to surround the use of placebos. Critics argue that the use of deceptive placebos—even in controlled research settings—violates the principle of informed consent and risks undermining patient trust. This debate is fueled by the fact that many patients, when informed that their treatment may be a placebo, could feel misled or less hopeful, potentially compromising the integrity of the therapeutic alliance. On the other side of the debate, proponents maintain that the placebo effect frequently contributes to positive clinical outcomes and that harnessing these benefits can be ethically justified if patients are adequately informed about the treatment rationale.

These controversies extend into the methodological realm as well. Some researchers have argued that the over-reliance on placebo controls could lead to underestimation of the true effects of active treatments when the placebo effect is unexpectedly potent. Moreover, the stratification of participants based on their likelihood to respond to placebo—a concept that has even been subject to patenting to optimize clinical trial designs—raises questions regarding the fairness and transparency of patient selection processes. Thus, the ethical debates not only encompass individual patient rights but also large-scale research practices and the need for reforms in research methodologies to minimize any adverse consequences of adult placebo use.

Impact on Research Outcomes

The role of the placebo extends far beyond the control group in clinical trials. The presence of a placebo group serves multiple purposes that directly affect the interpretation of research outcomes, the reliability of clinical conclusions, and the statistical significance of trial results.

Case Studies Demonstrating Placebo Impact

Numerous clinical trials have documented the tangible impact of the placebo effect on patient outcomes. For instance, in pain-related studies, patients receiving placebos have demonstrated clinically significant improvements in pain scores, sometimes approaching the efficacy of actual pharmacological interventions. Case studies in migraine treatment have shown that placebo responses can be as high as 30% to 50% when measured by subjective outcomes such as pain relief and symptom improvement. Similarly, research into the placebo effect in depression trials has repeatedly highlighted that improvements in mood and overall quality of life may occur even when patients receive a placebo treatment.

Furthermore, case studies from neuromodulation and neurology have demonstrated that the expectation-induced placebo effect can lead to observable changes in brain activity as measured by imaging studies. For example, in Parkinson’s disease, the administration of a placebo resulted in increased dopaminergic activation in the striatum, correlating with significant improvements in motor function. Such examples reinforce the notion that placebos are not inert bystander interventions but exert measurable clinical benefits through complex neurobiological pathways. These case studies, drawn from diverse fields ranging from pain management to neurology, underscore the multifaceted impact of the placebo effect on research outcomes.

Statistical Significance and Data Interpretation

In randomized controlled trials, statistical comparisons between the active treatment and the placebo are critical for evaluating drug efficacy and safety. The effect size measured in the active treatment group is often interpreted against the backdrop of the placebo response. As described in meta-analyses, when both the treatment and placebo groups demonstrate significant improvements, it is essential to employ sophisticated statistical techniques to dissect the specific treatment effect from the placebo effect.

Researchers often use methodologies that compare test statistics derived from both the treatment and placebo arms to evaluate whether the observed differences are statistically significant. In some cases, the use of placebo actions has even been integrated into advanced methods to assess statistical significance by comparing a desired action to a battery of placebo actions. This approach not only enhances the credibility of the findings but also minimizes the risk of false positive results that might arise from regression toward the mean. By aiding in robust data interpretation, placebos thereby contribute to improved assay sensitivity in clinical trials.

The analysis of placebo responses has also become a critical factor in refining clinical trial designs and in adjusting for non-specific effects that might otherwise confound the interpretation of efficacy. Through the incorporation of placebo data, researchers can better account for patient-specific factors such as expectation, natural disease progression, and spontaneous remission. Consequently, this enables a more accurate estimation of the true pharmacological effect, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the clinical trial outcomes.

Future Perspectives

As our understanding of the placebo effect continues to evolve, so too do the methods and applications of placebo use in clinical research. Future research directions are geared toward refining the role of placebos, reducing ethical concerns, and enhancing the therapeutic potential of non-specific effects through innovative methodological approaches.

Innovations in Placebo Use

Recent years have seen a significant shift in how placebos are conceptualized and utilized, particularly with the advent of open-label placebo trials. Unlike traditional placebo interventions that rely on deception, open-label placebos are administered transparently, with patients being informed that they are receiving an inert substance. Remarkably, studies have found that open-label placebos can still produce clinically significant improvements in conditions such as chronic pain, depression, and irritable bowel syndrome. This innovation challenges the conventional paradigm that deception is essential for eliciting a placebo response, and it opens up new avenues for ethically acceptable placebo use in clinical practice.

Another promising development is the integration of placebo response profiling into clinical trial designs. Several patents now focus on methods and systems for predicting or even eliminating placebo responders from clinical trials to optimize data analysis. The use of biomarkers and computational techniques to assess a subject’s likelihood of exhibiting a placebo response represents a cutting-edge approach that may enhance the precision of clinical trials and ultimately lead to more targeted therapeutic strategies. Moreover, system-oriented approaches, such as those used in protocol development involving crowdsourced feedback from diverse stakeholders, illustrate the potential for leveraging collective intelligence to refine placebo-controlled trial methodologies.

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite these innovations, several challenges remain in harnessing the full potential of placebo effects in clinical research. A key challenge is maintaining the delicate balance between methodological rigor and ethical considerations—especially when the use of placebos might compromise informed consent or patient trust. There is an ongoing need to enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the placebo effect, which involve a complex interplay of psychological, neurobiological, and social factors. Future research should focus on elucidating these pathways in greater detail, as well as determining the conditions under which placebo interventions can be ethically integrated into both clinical trials and routine clinical practice.

Another significant challenge lies in the heterogeneity of placebo responses among participants. Individual differences such as personality traits, prior treatment experiences, and genetic factors can substantially influence the magnitude and quality of the placebo effect. Addressing this variability requires the development of predictive models and the potential stratification of clinical trial participants based on their likelihood to respond to placebo interventions. Advances in machine learning and bioinformatics are poised to play a major role in achieving such stratification, which ultimately would lead to more personalized approaches in clinical therapeutics.

Furthermore, there is a need for consensus regarding what constitutes a clinically meaningful placebo response. While some studies indicate significant improvements in subjective outcomes, such as pain and mood, other studies have found limited objective benefits. Bridging this gap is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic impact of placebo mechanisms. Future research efforts must therefore integrate objective biomarkers with subjective reports to provide a holistic picture of the placebo response.

Lastly, research must address regulatory and practical issues associated with placebo use. Standardizing outcome measures, improving statistical analyses, and ensuring that ethical guidelines are uniformly applied across diverse research settings are critical steps needed to enhance the validity of placebo-controlled trials. Collaborative efforts among regulatory bodies, research institutions, and industry stakeholders will be crucial in overcoming these challenges and advancing the field.

Conclusion

In summary, the significance of the placebo in clinical research is multifaceted and profound. Historically, placebos have evolved from being viewed simply as inert “sugar pills” to being recognized as powerful phenomena capable of eliciting real neurobiological and psychobiological responses. They not only serve as essential control tools that help reduce bias and isolate the specific effects of therapeutic interventions, but they also contribute directly to patient outcomes through complex mechanisms such as expectation, conditioning, and the therapeutic alliance. Ethically, the use of placebos has been and continues to be a topic of vigorous debate, particularly regarding issues of deception and informed consent. Innovations, such as open-label placebos and methods for predicting placebo responsiveness, are paving the way for a future in which the placebo effect can be ethically integrated into clinical practice and research, thereby enhancing treatment outcomes and optimizing clinical trial design.

From a methodological perspective, placebo controls ensure robust comparisons in RCTs and help researchers disentangle the pharmacological effects of an intervention from the non-specific effects attributable to the patient-clinician relationship and individual expectations. Statistically, the incorporation of placebo data is vital for accurately interpreting treatment effects, reducing confounding influences, and enhancing assay sensitivity. Ethically, recent progress in open-label placebo studies has revolutionized our understanding of how non-deceptive placebo interventions might be used to achieve therapeutic benefits while upholding patient autonomy.

Looking to the future, embracing innovations in placebo research—including predictive modeling of placebo responsiveness and the integration of extensive patient feedback in clinical protocol development—is essential for advancing the field. While challenges remain, particularly concerning the heterogeneity of placebo responses and ethical debates regarding informed consent, future research promises to refine our understanding and application of placebo effects. This will not only improve data interpretation in clinical trials but may also lead to novel therapeutic strategies that harness the body’s inherent healing mechanisms.

In conclusion, placebos hold significant value in clinical research by providing a rigorous means to control for non-specific effects, enhancing our understanding of human physiology and psychology, and offering potential therapeutic benefits when used ethically and transparently. The continuous evolution of placebo research—from traditional blinded trials to innovative open-label studies and predictive assessments—emphasizes the enduring importance of the placebo both as a scientific tool and as a phenomenon worthy of further study. It is imperative that future research continues to address the methodological, ethical, and practical challenges associated with placebo use to fully harness its potential for improving patient outcomes and advancing medicine.

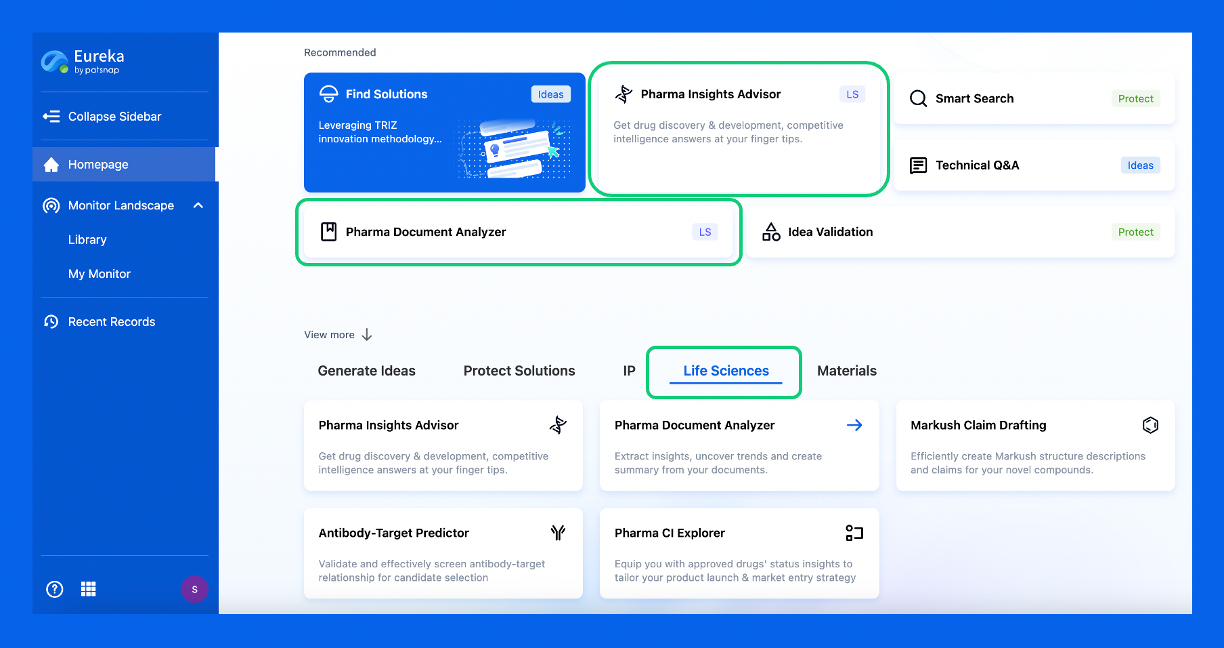

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.