Request Demo

What Oncolytic bacteria are being developed?

17 March 2025

Introduction to Oncolytic Bacteria

Oncolytic bacteria represent a novel class of therapeutic agents that take advantage of the unique microenvironment present in tumors. They are defined as live microbial agents that preferentially target, colonize, and lyse cancer cells while simultaneously stimulating antitumor immunity. The idea behind oncolytic bacteria marries the bio‐engineering of living organisms with the natural tumor’s vulnerabilities, such as hypoxia, necrosis, and immune suppression. These bacteria can not only exert a direct oncolytic effect through tumor cell lysis but also serve as vehicles to deliver a range of therapeutic payloads directly into the tumor microenvironment.

Definition and Basic Concepts

Oncolytic bacteria are live bacterial strains that are either naturally predisposed or genetically engineered to discriminate between malignant and healthy tissue. Their design capitalizes on several tumor-specific conditions: the porous vasculature of tumors, low pH, hypoxic regions, and an immunosuppressive milieu that collectively foster selective bacterial growth. By exploiting these conditions, oncolytic bacteria are able to accumulate preferentially at tumor sites, lysing the cancer cells either directly or by provoking a secondary immune-mediated attack. They are distinct from conventional chemotherapy agents and even from oncolytic viruses in that they possess the ability to self-amplify within the tumor environment, creating opportunities to continuously deliver anticancer agents and to modulate the local immune response.

Historical Development and Milestones

The concept of using bacteria to treat cancer is over a century old. Early observations, including those that led to the development of Coley’s toxin—a mixture of Streptococcus and Serratia species used in the late 19th century—highlighted spontaneous tumor regression following certain bacterial infections. Although these early treatments were largely empirical and limited by systemic toxicity, they laid the groundwork for the modern era of bacteriotherapy. Advances in our understanding of the tumor microenvironment and the advent of genetic engineering techniques in the late 20th and early 21st centuries have allowed researchers to revisit and refine these initial concepts. Today, through precision genetic modifications and synthetic biology tools such as CRISPR/Cas systems, oncolytic bacteria can be attenuated to reduce toxicity while enhancing their tumor-targeting and immune-stimulating capacities. These milestones have transitioned oncolytic bacteria from a serendipitous observation in ancient medicine to a rigorously investigated, next-generation modality in oncology.

Current Oncolytic Bacteria in Development

Recent research, particularly from structured sources at Synapse, has identified several bacterial species that have promising oncolytic potential. The focus of many studies is on engineering the innate properties of these microorganisms and modifying them further to achieve the desired level of safety and efficacy. Both wild‐type and genetically engineered variants are being developed with the potential to serve as monotherapies or as part of combination strategies in cancer treatment.

Types of Oncolytic Bacteria

A variety of bacterial species are under investigation for their oncolytic properties. Notable among these are:

• Salmonella spp.

– Attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium strains (for example, strain VNP20009) have been studied extensively due to their innate tumor‐targeting abilities. These strains are engineered by deleting virulence genes (e.g., msbB, purI) to reduce systemic toxicity and sepsis risk while maintaining their capacity to home to hypoxic tumor regions.

– Advanced modifications include adjusting the bacteria’s chemotactic responses so that they more effectively migrate toward gradients of tumor metabolites.

• Listeria monocytogenes

– This bacterium exhibits unique immunogenic properties. When genetically engineered to delete or modify genes involved in cell invasion, Listeria monocytogenes can be repurposed as an anticancer agent with reduced virulence while still retaining its strong ability to stimulate adaptive immune responses.

– Some oncolytic approaches involve Listeria-based vaccines that express tumor-associated antigens, thereby acting as both direct oncolytic agents and as stimulators of T-cell–mediated immunity.

• Clostridium spp.

– Obligate anaerobic Clostridium species, such as Clostridium novyi-NT, are adept at colonizing the necrotic and hypoxic cores of solid tumors. Their selective growth within the most resistant parts of the tumor microenvironment makes them ideal candidates for delivering oncolytic effects where conventional therapies fall short.

– Genetic engineering efforts focus on attenuating their toxin production to limit systemic toxicity, while preserving their ability to induce localized tumor lysis.

• Klebsiella spp. and Proteus spp.

– These species have also been noted for their preferential accumulation in tumor tissues. Their inclusion in the developing portfolio of oncolytic bacteria is based on their natural proclivity for tumor targeting.

– They are often in the early stages of development, with ongoing research aimed at clarifying their safety profiles and optimizing their oncolytic efficiency.

• Mycobacteria

– Certain non-tuberculous Mycobacterium strains have been explored for their potential oncolytic benefits, especially given their long history as immunomodulators. Genetic modifications in these bacteria help harness their capacity for tumor immune activation while mitigating adverse systemic effects.

• Streptococcus/Serratia (Coley’s Toxin Components)

– Early formulations of Coley’s toxin were composed of these bacteria. Modern research is revisiting these organisms with a focus on replicating the beneficial immune-stimulatory properties observed historically, though now with a precision-engineering approach to avoid the high systemic toxicity associated with unmodified strains.

• Bifidobacterium

– Although typically categorized as probiotics, certain Bifidobacterium species have been found to naturally accumulate in tumor regions, especially in hypoxic conditions. Their potential as oncolytic agents lies in their capacity for delivering therapeutic payloads via genetic engineering while maintaining a low immunogenic profile.

Leading Research Institutions and Companies

The development of oncolytic bacteria is a highly interdisciplinary effort transcending academia, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical corporations. Research institutions in North America, Europe, and Asia are at the forefront of this work. For example:

– Academic institutions such as Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and various European research centers have published pivotal studies demonstrating the tumor-targeting properties and immunomodulatory capabilities of engineered bacterial strains.

– Biotech companies are partnering with these institutions to take promising preclinical candidates into clinical trials. Although oncolytic virus therapy has garnered more mainstream clinical attention, specialized companies and startups focused on bacterial therapeutics are emerging rapidly, taking advantage of state-of-the-art synthetic biology and genetic engineering techniques.

– Collaborative efforts and consortia—sometimes involving industry leaders with robust clinical trial portfolios in oncology—are instrumental in advancing genetically engineered bacterial therapies into first-in-human studies.

Mechanisms of Action

The dual capacity of oncolytic bacteria to directly kill tumor cells and to modulate the host immune system is central to their therapeutic promise. Understanding these mechanisms from multiple perspectives enhances our ability to optimize their design.

How Oncolytic Bacteria Target Cancer Cells

Oncolytic bacteria exploit several characteristics of tumor biology to preferentially target cancer cells:

• Tumor Microenvironment Exploitation:

– Solid tumors are characterized by hypoxia, low pH, necrosis, and an immunosuppressive environment. These conditions not only support the survival of oncolytic bacteria but also impede the growth of normal cells. Bacteria such as Clostridium spp. thrive in these anaerobic zones and form colonies deep within the tumor tissue where other therapeutic agents cannot reach effectively.

– High interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) in tumors hinders the diffusion of conventional drugs. In contrast, motile bacteria using flagellar motility navigate these challenging physical barriers via chemotaxis toward specific nutrient gradients and tumor-specific molecules.

• Selective Colonization and Proliferation:

– Genetic engineering strategies have improved bacterial specificity. For example, modifications in Salmonella Typhimurium (e.g., deletion of the msbB, purI, or relA/SpoT genes) reduce virulence in normal tissues while enabling preferential growth within tumors. Once inside the tumor, these bacteria can replicate and create localized zones of infection, leading to lytic destruction of the cancer cells.

– Some engineered bacteria are designed to “sense” the glucose concentration or other metabolic markers within tumors. The ability to monitor such environmental cues ensures that bacterial proliferation is confined primarily to malignant tissues.

• Direct Tumor Cell Lysis and Toxin Production:

– Bacteria may directly induce cell death through mechanisms such as oncolysis, where invasion of the tumor cells leads to intracellular replication and subsequent cell rupture. Additionally, many bacteria secrete cytotoxic proteins or enzymes that can induce apoptosis or autophagy in nearby cancer cells.

– For instance, engineered strains of E. coli or Salmonella have been programmed to express specific toxins or prodrug-converting enzymes, which allow for localized conversion of non-toxic prodrugs into cytotoxic drugs directly within the tumor microenvironment. This strategy minimizes systemic side effects while maximizing antitumor efficacy.

Immune System Interactions

Oncolytic bacteria not only cause direct tumor cell death but also serve as potent stimulators of the immune system:

• Innate Immune Activation:

– As bacteria invade the tumor microenvironment, they are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on innate immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). This recognition leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that recruit additional immune cells to the tumor site.

– The bacterial cell wall components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in Salmonella or cell membrane motifs in Listeria activate toll-like receptors (TLRs), further amplifying an inflammatory response that can be harnessed to overcome the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

• Adaptive Immune Stimulation:

– The lysis of tumor cells by oncolytic bacteria releases tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) into the microenvironment. DCs capture these antigens and facilitate their presentation to T cells, thus stimulating a systemic adaptive immune response that may provide long-term immunological memory against the tumor.

– Additionally, engineered bacteria can be designed to express immune-stimulatory molecules such as GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) or other cytokines that help promote T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell activation. This dual action not only enhances the direct oncolytic effect but also turns “cold” tumors into “hot” ones by overcoming local immune tolerance.

• Synergistic Effects with Immunotherapy:

– The immunogenic cell death mediated by oncolytic bacteria often leads to the recruitment and activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. These T cells, in turn, can mediate bystander killing of not only infected cells but also distant tumor cells, thereby amplifying the therapeutic outcome.

– There is significant research exploring the combination of oncolytic bacterial therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. By modulating the tumor microenvironment and reigniting an immune response, these bacteria can improve the efficacy of therapies such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies.

Clinical Applications and Trials

The transition from preclinical models to human clinical trials is pivotal in establishing the safety and efficacy of oncolytic bacteria. Although many bacteria-based therapies are still in the early stages of clinical evaluation, the existing studies provide valuable insights into their potential.

Current Clinical Trials

Several first-in-human studies and early phase clinical trials have been initiated using oncolytic bacteria. For example:

• Salmonella Typhimurium VNP20009:

– This strain has undergone clinical evaluation to assess its safety profile when administered intravenously. Although early trials indicated a high safety margin with reduced pathogenicity, the antitumor efficacy has been moderate. Ongoing optimization efforts focus on coupling these strains with therapeutic transgenes or combining them with other anticancer agents to boost their activity.

• Listeria monocytogenes-based Vaccines:

– Several clinical trials have incorporated attenuated Listeria strains engineered to express tumor antigens in the treatment of cancers such as pancreatic, cervical, and melanoma. These trials are testing the dual benefit of oncolytic activity coupled with vaccination effects to induce robust T-cell responses.

• Clostridium-based Therapies:

– Preclinical and early-phase trials using Clostridium novyi-NT have demonstrated the bacteria’s ability to colonize hypoxic cores in solid tumors and induce localized cell death. These studies have paved the way for the design of combination therapies, wherein Clostridium-based oncolysis is combined with standard chemotherapy or radiotherapy to address limitations of conventional treatments.

• Combination Studies with Immunotherapy:

– There is growing interest in combining oncolytic bacteria with immune checkpoint inhibitors or other immunotherapeutic modalities. Early data suggest that the immune-modulatory effects of bacteria can sensitize tumors to checkpoint blockade, potentially translating into improved clinical outcomes. Ongoing trials are designed to elucidate the synergistic potential of these combination therapies.

Case Studies and Outcomes

While the majority of the clinical data remain in early phases, some case studies and preclinical animal models provide encouraging results:

• Animal Models:

– In multiple murine models, engineered Salmonella and Clostridium strains have shown a remarkable ability to reduce tumor growth, induce tumor regression, and even generate systemic antitumor immunity. These studies often report significant tumor:liver colonization ratios, indicating high specificity, and observed reductions in metastasis.

• Pilot Studies in Humans:

– Early-phase clinical trials with candidates such as VNP20009 have demonstrated acceptable safety profiles, validating the concept of utilizing live bacteria in a systemic setting. Although these studies have revealed challenges related to consistent tumor colonization and achieving robust clinical responses, they underscore the feasibility of proceeding to combination strategies and further genetic optimization.

• Immunotherapy Combination Strategies:

– Preliminary data from combination studies—where bacterial-based therapy is administered alongside checkpoint inhibitors—have shown enhanced immune infiltration into tumors and improved objective response rates. These early findings are particularly promising as they suggest that oncolytic bacteria may help overcome the limitations of immunotherapy in so-called “cold” tumors.

Challenges and Future Directions

As promising as oncolytic bacteria are for the treatment of cancer, several key challenges need to be addressed before they can be widely adopted in clinical practice.

Scientific and Technical Challenges

• Balancing Safety and Efficacy:

– One of the paramount challenges is achieving an optimal balance between attenuating bacterial virulence to ensure patient safety and retaining sufficient oncolytic potency. Genetic modifications (e.g., deleting virulence genes such as msbB, purI, relA, or SpoT) are essential but may sometimes reduce the bacteria’s capacity for oncolysis or immune stimulation.

– The inherent complexities of bacterial proliferation in vivo, including potential colonization in non-tumorous tissues, require further tuning through synthetic biology approaches.

• Genetic Stability and Control:

– Engineered bacteria must maintain genetic stability during in vivo applications. Mutations that arise during bacterial replication could inadvertently increase toxicity or reduce therapeutic efficacy. Strategies to control gene expression through genetic circuits and to confine bacterial replication selectively within tumors are active areas of research.

• Tumor Variability:

– The heterogeneous nature of tumors means that bacterial penetration, colonization, and proliferation can vary significantly from one tumor type to another. Factors such as the degree of vascularization, the extent of hypoxia, stromal composition, and the local immune environment all impact therapeutic outcomes.

– Developing tailored bacterial strains capable of responding to these diverse microenvironmental cues is critical for broadening the applicability of oncolytic bacteriotherapy.

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

• Regulatory Approval:

– Owing to their status as live biotherapeutic agents, oncolytic bacteria face a complex regulatory pathway that must ensure the safety, quality, and consistency of the product. Regulatory bodies require extensive non-clinical and clinical data to assess not only the efficacy but also potential off-target effects and systemic toxicity.

– Moreover, the environmental risk assessments to prevent unintended dissemination of genetically modified bacteria need to be comprehensive.

• Ethical Concerns:

– The administration of live, replicating organisms raises ethical issues related to patient monitoring, informed consent, and long-term follow-up. Strategies to efficiently clear bacteria from the body once a therapeutic effect has been achieved are crucial to minimize potential infections or adverse immune reactions.

– Transparency in communicating the novel risks associated with bacteriotherapy is essential to maintain public trust and regulatory acceptance.

Future Research Directions

• Combination Therapies:

– One of the most promising avenues for future research is the combination of oncolytic bacteria with other cancer therapies. Co-administration with immunotherapies, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or oncolytic viruses could synergistically improve treatment outcomes. For example, bacterial-mediated modulation of the immune environment could potentiate the effect of checkpoint inhibitors, leading to enhanced tumor clearance.

– Research should focus on the timing, dosing, and sequence of such combination treatments to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity.

• Advanced Synthetic Biology Approaches:

– The development of sophisticated genetic circuits that respond to the tumor microenvironment in real time is a critical area of future work. These circuits could control the expression of therapeutic payloads, regulate bacterial replication, and even initiate self-destruction programs once the tumor has been sufficiently treated.

– Directed evolution and CRISPR-based genome editing represent powerful tools that can further fine-tune bacterial vectors for optimal performance.

• Personalized Bacteriotherapy:

– As our understanding of tumor heterogeneity deepens, there is a growing opportunity to design personalized bacteriotherapeutics. Custom-engineered bacterial strains could be matched to the specific genetic, immunological, and metabolic profile of a patient’s tumor, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful treatment.

– Integrating high-throughput screening with microbiome analyses might facilitate the identification of novel bacterial strains or combinations thereof that are most effective for particular cancer types.

• Enhancing Tumor Penetration and Payload Delivery:

– Overcoming physical barriers such as high interstitial pressure and dense stroma remains a challenge for any therapeutic agent. Future research must address strategies to improve the homing and penetration of oncolytic bacteria. Engineering modifications—for instance, incorporating surface adhesins or chemotactic receptors—could enhance bacterial migration and retention within tumors.

– Additionally, novel methods for coupling nanoparticles or other drug delivery platforms to bacteria are being explored, thereby offering an integrated approach for delivering high concentrations of cytotoxic or immunomodulatory agents directly to the tumor.

• Long-Term Safety and Immune Memory:

– In-depth investigations into the long-term interaction between oncolytic bacteria and the host immune system will be required. Understanding how these therapies induce durable antitumor immunity without triggering autoimmunity or persistent inflammation is paramount.

– Future studies should also evaluate the potential for oncolytic bacteriotherapy to create a “vaccination” effect, whereby the immune system retains memory of tumor antigens and protects against recurrence.

Conclusion

Oncolytic bacteria are emerging as highly promising agents in the fight against cancer, owing to their innate ability to selectively target and colonize tumors, their capacity to deliver cytotoxic or immunostimulatory payloads, and their potential to reprogram the tumor microenvironment toward an antitumor state. The journey of oncolytic bacteria—from early observations of spontaneous tumor regression following infections (exemplified by historical treatments like Coley’s toxin) to the modern era of advanced genetic engineering—demonstrates remarkable progress. Today, a diverse portfolio of bacterial species is under active development, including attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium spp., Klebsiella, Proteus, Mycobacteria, and even probiotic strains such as Bifidobacterium. Each type capitalizes on unique mechanisms such as chemotaxis toward tumor metabolites, replication in hypoxic conditions, direct oncolysis through toxin production, and the induction of both innate and adaptive immune responses.

The current research landscape is characterized by robust collaborations between academic research institutions and biotechnology companies worldwide. These organizations are diligently optimizing bacterial strains to achieve the ideal balance of safety and efficacy. Mechanistic studies have revealed that oncolytic bacteria not only kill tumor cells directly but also disrupt the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, leading to the recruitment of dendritic cells and T lymphocytes that facilitate long-term anticancer immunity. Various clinical trials have been initiated—most notably with Salmonella Typhimurium strain VNP20009 and Listeria-based vaccine candidates—with early data confirming a high safety profile, although challenges in achieving robust tumor regression persist.

Looking toward the future, key challenges such as optimizing genetic stability, ensuring tumor-specific proliferation, and integrating bacteriotherapy with other therapeutic modalities must be addressed. Regulatory hurdles and ethical considerations regarding the use of live, genetically modified organisms will require concerted efforts from researchers, clinicians, and policymakers. Future research directions include the design of advanced genetic circuits for controlled payload release, combination treatments with checkpoint inhibitors, and the development of personalized bacteriotherapeutics that are tailored to the unique microenvironmental and genetic characteristics of individual tumors.

In summary, the development of oncolytic bacteria embodies a general-specific-general paradigm: the general concept of using bacteria as anti-cancer agents has evolved into specific, genetically engineered strains that exhibit precise tumor targeting and immune stimulation, which in turn holds the promise of revolutionizing cancer treatment on a broader scale. With continued innovation, rigorous clinical evaluation, and strategic regulatory pathways, oncolytic bacteria are poised to become a powerful addition to the oncology therapeutic arsenal, offering new hope for patients battling a wide array of malignancies.

Oncolytic bacteria represent a novel class of therapeutic agents that take advantage of the unique microenvironment present in tumors. They are defined as live microbial agents that preferentially target, colonize, and lyse cancer cells while simultaneously stimulating antitumor immunity. The idea behind oncolytic bacteria marries the bio‐engineering of living organisms with the natural tumor’s vulnerabilities, such as hypoxia, necrosis, and immune suppression. These bacteria can not only exert a direct oncolytic effect through tumor cell lysis but also serve as vehicles to deliver a range of therapeutic payloads directly into the tumor microenvironment.

Definition and Basic Concepts

Oncolytic bacteria are live bacterial strains that are either naturally predisposed or genetically engineered to discriminate between malignant and healthy tissue. Their design capitalizes on several tumor-specific conditions: the porous vasculature of tumors, low pH, hypoxic regions, and an immunosuppressive milieu that collectively foster selective bacterial growth. By exploiting these conditions, oncolytic bacteria are able to accumulate preferentially at tumor sites, lysing the cancer cells either directly or by provoking a secondary immune-mediated attack. They are distinct from conventional chemotherapy agents and even from oncolytic viruses in that they possess the ability to self-amplify within the tumor environment, creating opportunities to continuously deliver anticancer agents and to modulate the local immune response.

Historical Development and Milestones

The concept of using bacteria to treat cancer is over a century old. Early observations, including those that led to the development of Coley’s toxin—a mixture of Streptococcus and Serratia species used in the late 19th century—highlighted spontaneous tumor regression following certain bacterial infections. Although these early treatments were largely empirical and limited by systemic toxicity, they laid the groundwork for the modern era of bacteriotherapy. Advances in our understanding of the tumor microenvironment and the advent of genetic engineering techniques in the late 20th and early 21st centuries have allowed researchers to revisit and refine these initial concepts. Today, through precision genetic modifications and synthetic biology tools such as CRISPR/Cas systems, oncolytic bacteria can be attenuated to reduce toxicity while enhancing their tumor-targeting and immune-stimulating capacities. These milestones have transitioned oncolytic bacteria from a serendipitous observation in ancient medicine to a rigorously investigated, next-generation modality in oncology.

Current Oncolytic Bacteria in Development

Recent research, particularly from structured sources at Synapse, has identified several bacterial species that have promising oncolytic potential. The focus of many studies is on engineering the innate properties of these microorganisms and modifying them further to achieve the desired level of safety and efficacy. Both wild‐type and genetically engineered variants are being developed with the potential to serve as monotherapies or as part of combination strategies in cancer treatment.

Types of Oncolytic Bacteria

A variety of bacterial species are under investigation for their oncolytic properties. Notable among these are:

• Salmonella spp.

– Attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium strains (for example, strain VNP20009) have been studied extensively due to their innate tumor‐targeting abilities. These strains are engineered by deleting virulence genes (e.g., msbB, purI) to reduce systemic toxicity and sepsis risk while maintaining their capacity to home to hypoxic tumor regions.

– Advanced modifications include adjusting the bacteria’s chemotactic responses so that they more effectively migrate toward gradients of tumor metabolites.

• Listeria monocytogenes

– This bacterium exhibits unique immunogenic properties. When genetically engineered to delete or modify genes involved in cell invasion, Listeria monocytogenes can be repurposed as an anticancer agent with reduced virulence while still retaining its strong ability to stimulate adaptive immune responses.

– Some oncolytic approaches involve Listeria-based vaccines that express tumor-associated antigens, thereby acting as both direct oncolytic agents and as stimulators of T-cell–mediated immunity.

• Clostridium spp.

– Obligate anaerobic Clostridium species, such as Clostridium novyi-NT, are adept at colonizing the necrotic and hypoxic cores of solid tumors. Their selective growth within the most resistant parts of the tumor microenvironment makes them ideal candidates for delivering oncolytic effects where conventional therapies fall short.

– Genetic engineering efforts focus on attenuating their toxin production to limit systemic toxicity, while preserving their ability to induce localized tumor lysis.

• Klebsiella spp. and Proteus spp.

– These species have also been noted for their preferential accumulation in tumor tissues. Their inclusion in the developing portfolio of oncolytic bacteria is based on their natural proclivity for tumor targeting.

– They are often in the early stages of development, with ongoing research aimed at clarifying their safety profiles and optimizing their oncolytic efficiency.

• Mycobacteria

– Certain non-tuberculous Mycobacterium strains have been explored for their potential oncolytic benefits, especially given their long history as immunomodulators. Genetic modifications in these bacteria help harness their capacity for tumor immune activation while mitigating adverse systemic effects.

• Streptococcus/Serratia (Coley’s Toxin Components)

– Early formulations of Coley’s toxin were composed of these bacteria. Modern research is revisiting these organisms with a focus on replicating the beneficial immune-stimulatory properties observed historically, though now with a precision-engineering approach to avoid the high systemic toxicity associated with unmodified strains.

• Bifidobacterium

– Although typically categorized as probiotics, certain Bifidobacterium species have been found to naturally accumulate in tumor regions, especially in hypoxic conditions. Their potential as oncolytic agents lies in their capacity for delivering therapeutic payloads via genetic engineering while maintaining a low immunogenic profile.

Leading Research Institutions and Companies

The development of oncolytic bacteria is a highly interdisciplinary effort transcending academia, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical corporations. Research institutions in North America, Europe, and Asia are at the forefront of this work. For example:

– Academic institutions such as Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and various European research centers have published pivotal studies demonstrating the tumor-targeting properties and immunomodulatory capabilities of engineered bacterial strains.

– Biotech companies are partnering with these institutions to take promising preclinical candidates into clinical trials. Although oncolytic virus therapy has garnered more mainstream clinical attention, specialized companies and startups focused on bacterial therapeutics are emerging rapidly, taking advantage of state-of-the-art synthetic biology and genetic engineering techniques.

– Collaborative efforts and consortia—sometimes involving industry leaders with robust clinical trial portfolios in oncology—are instrumental in advancing genetically engineered bacterial therapies into first-in-human studies.

Mechanisms of Action

The dual capacity of oncolytic bacteria to directly kill tumor cells and to modulate the host immune system is central to their therapeutic promise. Understanding these mechanisms from multiple perspectives enhances our ability to optimize their design.

How Oncolytic Bacteria Target Cancer Cells

Oncolytic bacteria exploit several characteristics of tumor biology to preferentially target cancer cells:

• Tumor Microenvironment Exploitation:

– Solid tumors are characterized by hypoxia, low pH, necrosis, and an immunosuppressive environment. These conditions not only support the survival of oncolytic bacteria but also impede the growth of normal cells. Bacteria such as Clostridium spp. thrive in these anaerobic zones and form colonies deep within the tumor tissue where other therapeutic agents cannot reach effectively.

– High interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) in tumors hinders the diffusion of conventional drugs. In contrast, motile bacteria using flagellar motility navigate these challenging physical barriers via chemotaxis toward specific nutrient gradients and tumor-specific molecules.

• Selective Colonization and Proliferation:

– Genetic engineering strategies have improved bacterial specificity. For example, modifications in Salmonella Typhimurium (e.g., deletion of the msbB, purI, or relA/SpoT genes) reduce virulence in normal tissues while enabling preferential growth within tumors. Once inside the tumor, these bacteria can replicate and create localized zones of infection, leading to lytic destruction of the cancer cells.

– Some engineered bacteria are designed to “sense” the glucose concentration or other metabolic markers within tumors. The ability to monitor such environmental cues ensures that bacterial proliferation is confined primarily to malignant tissues.

• Direct Tumor Cell Lysis and Toxin Production:

– Bacteria may directly induce cell death through mechanisms such as oncolysis, where invasion of the tumor cells leads to intracellular replication and subsequent cell rupture. Additionally, many bacteria secrete cytotoxic proteins or enzymes that can induce apoptosis or autophagy in nearby cancer cells.

– For instance, engineered strains of E. coli or Salmonella have been programmed to express specific toxins or prodrug-converting enzymes, which allow for localized conversion of non-toxic prodrugs into cytotoxic drugs directly within the tumor microenvironment. This strategy minimizes systemic side effects while maximizing antitumor efficacy.

Immune System Interactions

Oncolytic bacteria not only cause direct tumor cell death but also serve as potent stimulators of the immune system:

• Innate Immune Activation:

– As bacteria invade the tumor microenvironment, they are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on innate immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). This recognition leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that recruit additional immune cells to the tumor site.

– The bacterial cell wall components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in Salmonella or cell membrane motifs in Listeria activate toll-like receptors (TLRs), further amplifying an inflammatory response that can be harnessed to overcome the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

• Adaptive Immune Stimulation:

– The lysis of tumor cells by oncolytic bacteria releases tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) into the microenvironment. DCs capture these antigens and facilitate their presentation to T cells, thus stimulating a systemic adaptive immune response that may provide long-term immunological memory against the tumor.

– Additionally, engineered bacteria can be designed to express immune-stimulatory molecules such as GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) or other cytokines that help promote T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell activation. This dual action not only enhances the direct oncolytic effect but also turns “cold” tumors into “hot” ones by overcoming local immune tolerance.

• Synergistic Effects with Immunotherapy:

– The immunogenic cell death mediated by oncolytic bacteria often leads to the recruitment and activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. These T cells, in turn, can mediate bystander killing of not only infected cells but also distant tumor cells, thereby amplifying the therapeutic outcome.

– There is significant research exploring the combination of oncolytic bacterial therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. By modulating the tumor microenvironment and reigniting an immune response, these bacteria can improve the efficacy of therapies such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies.

Clinical Applications and Trials

The transition from preclinical models to human clinical trials is pivotal in establishing the safety and efficacy of oncolytic bacteria. Although many bacteria-based therapies are still in the early stages of clinical evaluation, the existing studies provide valuable insights into their potential.

Current Clinical Trials

Several first-in-human studies and early phase clinical trials have been initiated using oncolytic bacteria. For example:

• Salmonella Typhimurium VNP20009:

– This strain has undergone clinical evaluation to assess its safety profile when administered intravenously. Although early trials indicated a high safety margin with reduced pathogenicity, the antitumor efficacy has been moderate. Ongoing optimization efforts focus on coupling these strains with therapeutic transgenes or combining them with other anticancer agents to boost their activity.

• Listeria monocytogenes-based Vaccines:

– Several clinical trials have incorporated attenuated Listeria strains engineered to express tumor antigens in the treatment of cancers such as pancreatic, cervical, and melanoma. These trials are testing the dual benefit of oncolytic activity coupled with vaccination effects to induce robust T-cell responses.

• Clostridium-based Therapies:

– Preclinical and early-phase trials using Clostridium novyi-NT have demonstrated the bacteria’s ability to colonize hypoxic cores in solid tumors and induce localized cell death. These studies have paved the way for the design of combination therapies, wherein Clostridium-based oncolysis is combined with standard chemotherapy or radiotherapy to address limitations of conventional treatments.

• Combination Studies with Immunotherapy:

– There is growing interest in combining oncolytic bacteria with immune checkpoint inhibitors or other immunotherapeutic modalities. Early data suggest that the immune-modulatory effects of bacteria can sensitize tumors to checkpoint blockade, potentially translating into improved clinical outcomes. Ongoing trials are designed to elucidate the synergistic potential of these combination therapies.

Case Studies and Outcomes

While the majority of the clinical data remain in early phases, some case studies and preclinical animal models provide encouraging results:

• Animal Models:

– In multiple murine models, engineered Salmonella and Clostridium strains have shown a remarkable ability to reduce tumor growth, induce tumor regression, and even generate systemic antitumor immunity. These studies often report significant tumor:liver colonization ratios, indicating high specificity, and observed reductions in metastasis.

• Pilot Studies in Humans:

– Early-phase clinical trials with candidates such as VNP20009 have demonstrated acceptable safety profiles, validating the concept of utilizing live bacteria in a systemic setting. Although these studies have revealed challenges related to consistent tumor colonization and achieving robust clinical responses, they underscore the feasibility of proceeding to combination strategies and further genetic optimization.

• Immunotherapy Combination Strategies:

– Preliminary data from combination studies—where bacterial-based therapy is administered alongside checkpoint inhibitors—have shown enhanced immune infiltration into tumors and improved objective response rates. These early findings are particularly promising as they suggest that oncolytic bacteria may help overcome the limitations of immunotherapy in so-called “cold” tumors.

Challenges and Future Directions

As promising as oncolytic bacteria are for the treatment of cancer, several key challenges need to be addressed before they can be widely adopted in clinical practice.

Scientific and Technical Challenges

• Balancing Safety and Efficacy:

– One of the paramount challenges is achieving an optimal balance between attenuating bacterial virulence to ensure patient safety and retaining sufficient oncolytic potency. Genetic modifications (e.g., deleting virulence genes such as msbB, purI, relA, or SpoT) are essential but may sometimes reduce the bacteria’s capacity for oncolysis or immune stimulation.

– The inherent complexities of bacterial proliferation in vivo, including potential colonization in non-tumorous tissues, require further tuning through synthetic biology approaches.

• Genetic Stability and Control:

– Engineered bacteria must maintain genetic stability during in vivo applications. Mutations that arise during bacterial replication could inadvertently increase toxicity or reduce therapeutic efficacy. Strategies to control gene expression through genetic circuits and to confine bacterial replication selectively within tumors are active areas of research.

• Tumor Variability:

– The heterogeneous nature of tumors means that bacterial penetration, colonization, and proliferation can vary significantly from one tumor type to another. Factors such as the degree of vascularization, the extent of hypoxia, stromal composition, and the local immune environment all impact therapeutic outcomes.

– Developing tailored bacterial strains capable of responding to these diverse microenvironmental cues is critical for broadening the applicability of oncolytic bacteriotherapy.

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

• Regulatory Approval:

– Owing to their status as live biotherapeutic agents, oncolytic bacteria face a complex regulatory pathway that must ensure the safety, quality, and consistency of the product. Regulatory bodies require extensive non-clinical and clinical data to assess not only the efficacy but also potential off-target effects and systemic toxicity.

– Moreover, the environmental risk assessments to prevent unintended dissemination of genetically modified bacteria need to be comprehensive.

• Ethical Concerns:

– The administration of live, replicating organisms raises ethical issues related to patient monitoring, informed consent, and long-term follow-up. Strategies to efficiently clear bacteria from the body once a therapeutic effect has been achieved are crucial to minimize potential infections or adverse immune reactions.

– Transparency in communicating the novel risks associated with bacteriotherapy is essential to maintain public trust and regulatory acceptance.

Future Research Directions

• Combination Therapies:

– One of the most promising avenues for future research is the combination of oncolytic bacteria with other cancer therapies. Co-administration with immunotherapies, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or oncolytic viruses could synergistically improve treatment outcomes. For example, bacterial-mediated modulation of the immune environment could potentiate the effect of checkpoint inhibitors, leading to enhanced tumor clearance.

– Research should focus on the timing, dosing, and sequence of such combination treatments to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity.

• Advanced Synthetic Biology Approaches:

– The development of sophisticated genetic circuits that respond to the tumor microenvironment in real time is a critical area of future work. These circuits could control the expression of therapeutic payloads, regulate bacterial replication, and even initiate self-destruction programs once the tumor has been sufficiently treated.

– Directed evolution and CRISPR-based genome editing represent powerful tools that can further fine-tune bacterial vectors for optimal performance.

• Personalized Bacteriotherapy:

– As our understanding of tumor heterogeneity deepens, there is a growing opportunity to design personalized bacteriotherapeutics. Custom-engineered bacterial strains could be matched to the specific genetic, immunological, and metabolic profile of a patient’s tumor, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful treatment.

– Integrating high-throughput screening with microbiome analyses might facilitate the identification of novel bacterial strains or combinations thereof that are most effective for particular cancer types.

• Enhancing Tumor Penetration and Payload Delivery:

– Overcoming physical barriers such as high interstitial pressure and dense stroma remains a challenge for any therapeutic agent. Future research must address strategies to improve the homing and penetration of oncolytic bacteria. Engineering modifications—for instance, incorporating surface adhesins or chemotactic receptors—could enhance bacterial migration and retention within tumors.

– Additionally, novel methods for coupling nanoparticles or other drug delivery platforms to bacteria are being explored, thereby offering an integrated approach for delivering high concentrations of cytotoxic or immunomodulatory agents directly to the tumor.

• Long-Term Safety and Immune Memory:

– In-depth investigations into the long-term interaction between oncolytic bacteria and the host immune system will be required. Understanding how these therapies induce durable antitumor immunity without triggering autoimmunity or persistent inflammation is paramount.

– Future studies should also evaluate the potential for oncolytic bacteriotherapy to create a “vaccination” effect, whereby the immune system retains memory of tumor antigens and protects against recurrence.

Conclusion

Oncolytic bacteria are emerging as highly promising agents in the fight against cancer, owing to their innate ability to selectively target and colonize tumors, their capacity to deliver cytotoxic or immunostimulatory payloads, and their potential to reprogram the tumor microenvironment toward an antitumor state. The journey of oncolytic bacteria—from early observations of spontaneous tumor regression following infections (exemplified by historical treatments like Coley’s toxin) to the modern era of advanced genetic engineering—demonstrates remarkable progress. Today, a diverse portfolio of bacterial species is under active development, including attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium spp., Klebsiella, Proteus, Mycobacteria, and even probiotic strains such as Bifidobacterium. Each type capitalizes on unique mechanisms such as chemotaxis toward tumor metabolites, replication in hypoxic conditions, direct oncolysis through toxin production, and the induction of both innate and adaptive immune responses.

The current research landscape is characterized by robust collaborations between academic research institutions and biotechnology companies worldwide. These organizations are diligently optimizing bacterial strains to achieve the ideal balance of safety and efficacy. Mechanistic studies have revealed that oncolytic bacteria not only kill tumor cells directly but also disrupt the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, leading to the recruitment of dendritic cells and T lymphocytes that facilitate long-term anticancer immunity. Various clinical trials have been initiated—most notably with Salmonella Typhimurium strain VNP20009 and Listeria-based vaccine candidates—with early data confirming a high safety profile, although challenges in achieving robust tumor regression persist.

Looking toward the future, key challenges such as optimizing genetic stability, ensuring tumor-specific proliferation, and integrating bacteriotherapy with other therapeutic modalities must be addressed. Regulatory hurdles and ethical considerations regarding the use of live, genetically modified organisms will require concerted efforts from researchers, clinicians, and policymakers. Future research directions include the design of advanced genetic circuits for controlled payload release, combination treatments with checkpoint inhibitors, and the development of personalized bacteriotherapeutics that are tailored to the unique microenvironmental and genetic characteristics of individual tumors.

In summary, the development of oncolytic bacteria embodies a general-specific-general paradigm: the general concept of using bacteria as anti-cancer agents has evolved into specific, genetically engineered strains that exhibit precise tumor targeting and immune stimulation, which in turn holds the promise of revolutionizing cancer treatment on a broader scale. With continued innovation, rigorous clinical evaluation, and strategic regulatory pathways, oncolytic bacteria are poised to become a powerful addition to the oncology therapeutic arsenal, offering new hope for patients battling a wide array of malignancies.

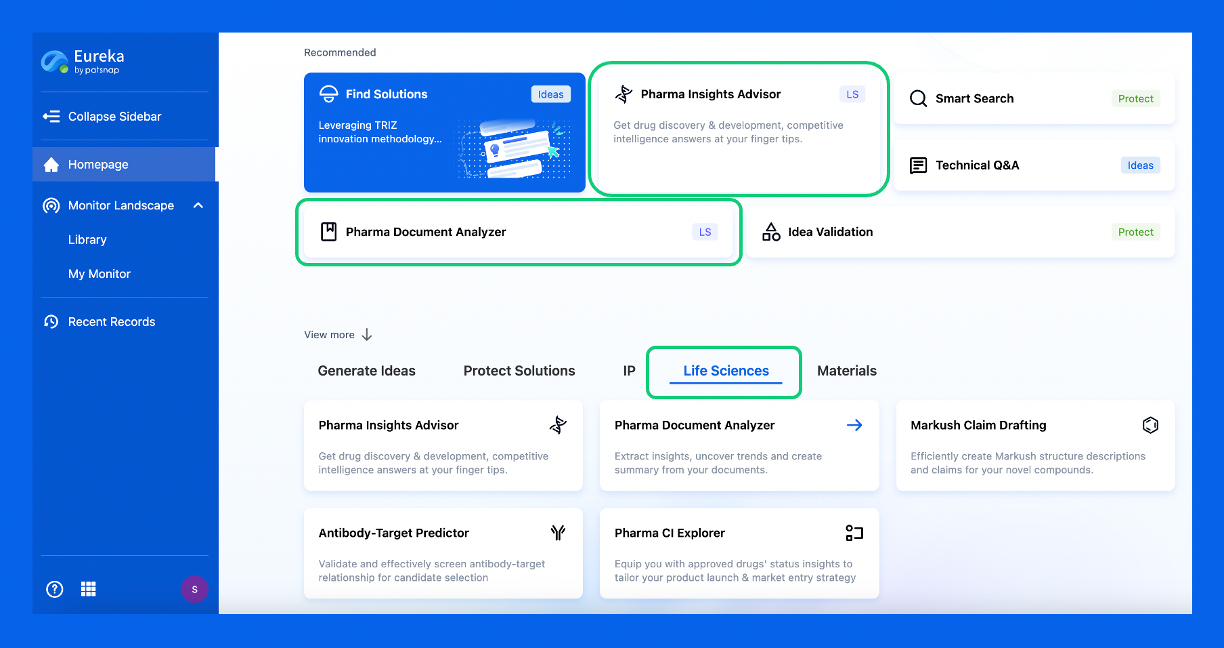

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.