Request Demo

Last update 27 Feb 2026

Paclitaxel/Pimecrolimus

Last update 27 Feb 2026

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Non-degrading molecular glue |

Synonyms Symbio |

Target |

Action inhibitors |

Mechanism CaN inhibitors(Calcineurin inhibitors), FKBPs inhibitors(FKBP prolyl isomerases inhibitors), Tubulin inhibitors |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization- |

Inactive Organization |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest PhasePendingPhase 3 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC43H68ClNO11 |

InChIKeyKASDHRXLYQOAKZ-XDSKOBMDSA-N |

CAS Registry137071-32-0 |

View All Structures (2)

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | Belgium | - | - |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | France | - | - |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | Germany | - | - |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | Israel | - | - |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | United Kingdom | - | - |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | - | - | |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | - | - | |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Phase 3 | - | - |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

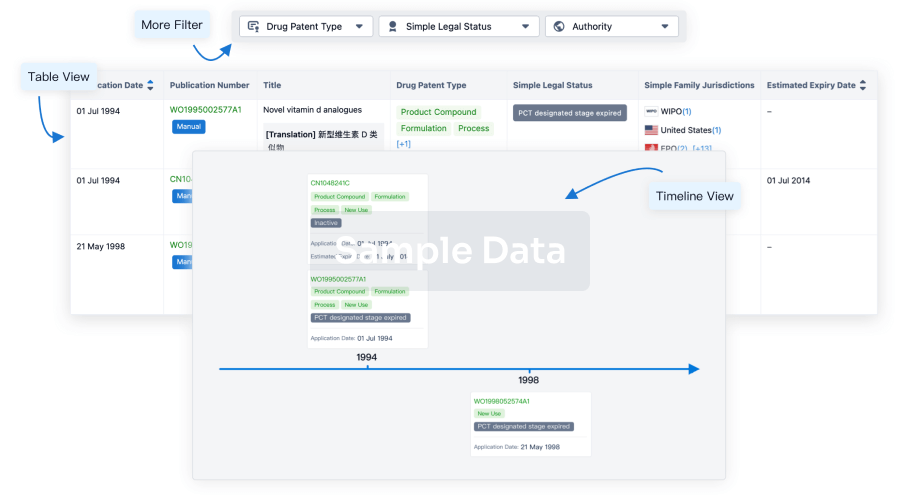

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

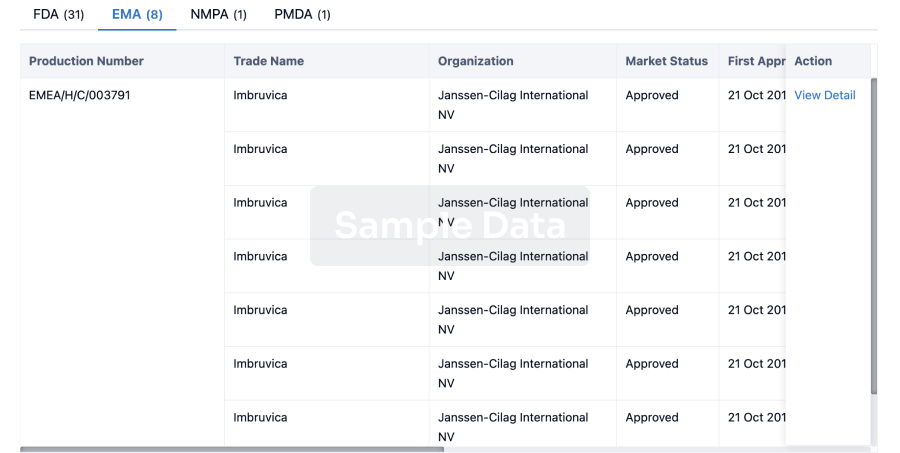

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

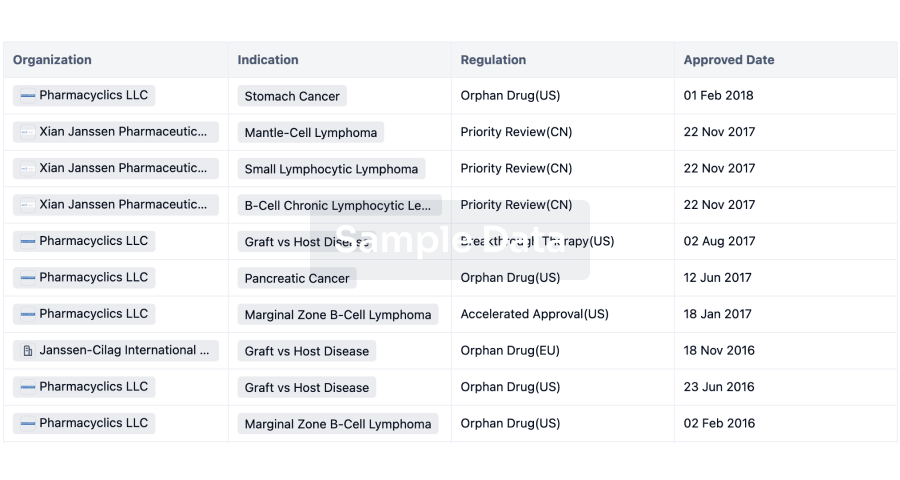

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free