Request Demo

Last update 20 Nov 2025

BTL-TML

Last update 20 Nov 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms [(o-carboxyphenyl)thio]ethylmercury sodium salt, BTL-TML-COVID, BTL-TML-HSV + [12] |

Target- |

Action inhibitors |

Mechanism Virus replication inhibitors |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization |

Inactive Organization- |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC9H9HgNaO2S |

InChIKeySKLIKZFOTSKEKY-UHFFFAOYSA-L |

CAS Registry54-64-8 |

Related

4

Clinical Trials associated with BTL-TMLNCT04522830

A Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Phase 2 Trial of Sublingual Low-Dose Thimerosal in Adults With Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Clinical trial to compare sublingual low does thimerosal in adults that have symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 Infection against placebo to show a difference in physical characteristics and viral levels.

Start Date30 Jul 2020 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT01902303

Evaluation of Cold Sore Treatments on UV Induced Cold Sores

The purpose of this study is to determine if a new drug treatment is effective to block the development of a cold sore lesion following Ultra Violet (UV) exposure.

Start Date01 Jul 2013 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT01308424

A Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel, Placebo-controlled Study for the Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of BTL-TML-HSV for the Treatment of Recurrent Symptomatic Oral Herpes Virus Infection

The purpose of this study is to determine if a new treatment is effective for the treatment of recurrent symptomatic oral herpes virus infections.

Start Date01 Jan 2011 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with BTL-TML

Login to view more data

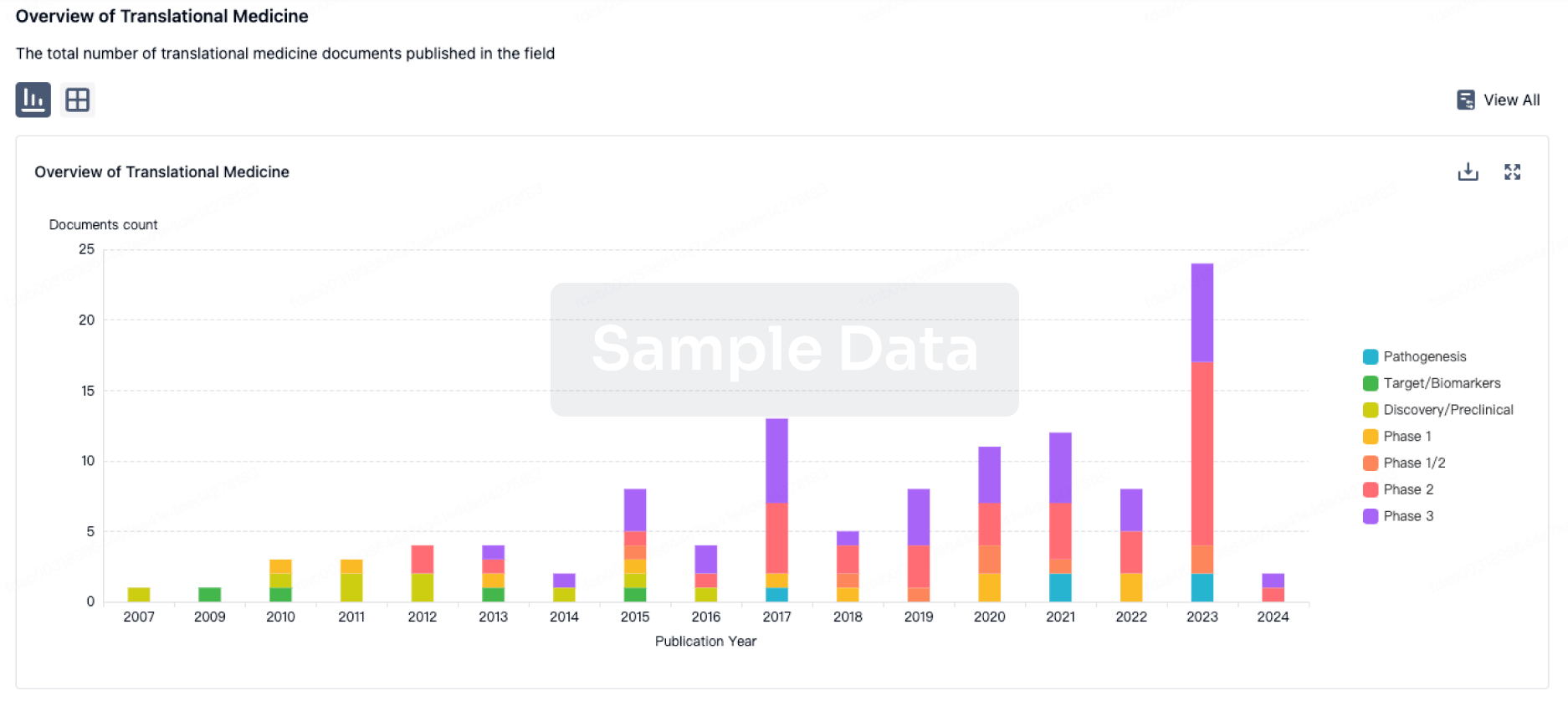

100 Translational Medicine associated with BTL-TML

Login to view more data

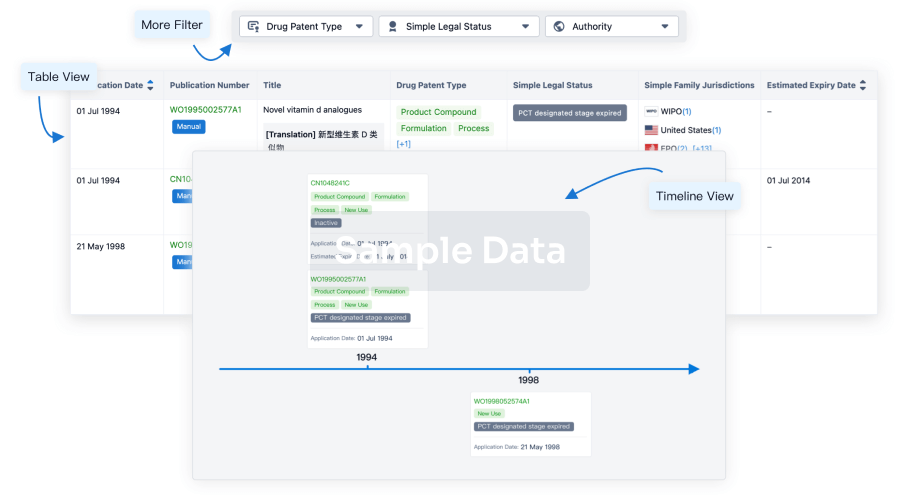

100 Patents (Medical) associated with BTL-TML

Login to view more data

1,333

Literatures (Medical) associated with BTL-TML06 Sep 2025·Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine]

[Distribution characteristics and clinical significance of exposed allergens in different age groups].

Article

Author: Kong, R ; Wang, L M ; Zhao, Y

Objective: This study aimed to assess the patch test positivity rate, allergen distribution, and their associations with demographic characteristics and immune indicators in patients with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Methods: A retrospective medical record analysis was conducted on 402 patients suspected of ACD (338 females, median age 38 years; 64 males, median age 43 years) seen at Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University between June 2023 and June 2024. Standard patch tests (using 100 haptens from the Chinese baseline series) were administered, and serum total IgE and eosinophil levels were measured. Statistical analyses included chi-square tests, t-tests/Mann-Whitney U tests for group comparisons, and Spearman correlation for associations. Results: The overall patch test positivity rate among the 402 patients was 62.69% (252/402), with 85.71% (216/252) showing sensitivity to the top 21 allergens. Predominantly, the affected individuals were females (84.26%, 182/216) aged 19-35 years (36.57%, 79/216). The primary sensitizers were cobalt chloride (22.89%, 92/402) and nickel sulfate (19.90%, 80/402). The highest proportion of severe reactions (+++) was observed with thimerosal (10/16). Males exhibited significantly higher positive risks for carba mix (OR=5.10, P=0.002) and octyl gallate (OR=2.64, P=0.047) compared to females. The age-stratified results revealed that the cobalt chloride positive rate was abnormally increased to 76.72% (50/65) in the 36-50 years age group, a rate significantly higher than those observed in the ≤18 years group (20.00%), the 19-35 years group (21.51%), and the >50 years group (16.13%; all P<0.05). In contrast, the >50 years age group exhibited the highest positive rate for nickel sulfate among all age groups at 20.96% (13/62). No significant correlations were found between the number of positive patch tests, reaction intensity (average/maximum), and total IgE (r=-0.075-0.063), absolute and percentage of eosinophils (P>0.05). Clinically, eczema prevalence in the>50 age group was 22.58% (14/62), with ACD complicated by allergic dermatitis being the most common (16.67%, 36/216). Conclusion: Nickel sulfate and cobalt chloride are primary sensitizers for ACD. Sensitization patterns across age groups are similar and unrelated to IgE/EOS levels. The higher incidence of severe reactions to thimerosal may be linked to heightened sensitization to mercury-containing products like vaccine preservatives. The notably increased cobalt chloride positivity in the 36-50 age group suggests a unique exposure risk, while the higher prevalence in females may be associated with contact with nickel/cobalt-containing items such as jewelry and cosmetics.

01 Sep 2025·EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICS AND BIOPHARMACEUTICS

Compatibility of antimicrobial preservatives with therapeutic bacteriophages of the genera Pbunavirus and Kayvirus

Article

Author: Laichmanová, Monika ; Pantůček, Roman ; Jelínek, Petr ; Šoóš, Miroslav ; Smetanová, Soňa ; Komárková, Marie ; Benešík, Martin ; Vinco, Adam ; Procházková, Tereza ; Botka, Tibor ; Moša, Marek

Implementing bacteriophages into dosage forms is a significant step for the practical application of phage therapy. While designing a dosage form, bacteriophages as active ingredients may be exposed to excipients, guaranteeing microbial quality. However, only a few antimicrobial preservatives have been studied regarding their interaction with bacteriophages during long-term storage. Here, the stability of the staphylococcal Kayvirus and pseudomonal Pbunavirus with twelve commonly used preservatives was monitored for thirteen weeks to assess the risk of destabilisation of phage suspensions by excipients. The effectiveness of preservatives on the test bacteria, yeast and mould was determined using a microdilution method and the phage lytic activity by plaque enumeration. The antimicrobial activity of preservatives with bacteriophages was confirmed, except benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine digluconate, which showed precipitation and were classified as incompatible. A complete loss of phage potency in both tested phages occurred with diazolidinyl urea and in Kayvirus with benzalkonium chloride. For both phages, a slight decrease in titer, by one order of magnitude, was observed with m-cresol, sodium propionate, sodium benzoate, and phenylethyl alcohol. For Kayvirus, thimerosal, parabens, and mono propylene glycol and for Pbunavirus, phenoxyethanol also met the criteria. The decrease by two or more orders was determined for the remaining cases. This study helps select antimicrobial preservatives for optimizing dosage formulations with the therapeutically applicable bacteriophages.

01 Aug 2025·VACCINE

Safety and immunogenicity of thiomersal-free recombinant hepatitis E vaccine: A randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study

Article

Author: Yu, Xiaoshan ; Chen, Shasha ; Zhang, Dengxiang ; Xie, Fangqin ; Huang, Qinbiao ; Zhong, Sumei ; Wang, Xiujuan ; Zhang, Qiufen ; Zhang, Dongjuan ; Li, Junrong ; Wang, Rui

INTRODUCTION:

The first recombinant hepatitis E vaccine (Escherichia Coli), Hecolin® (Xiamen Innovax, China), was approved for people aged ≥16 years. Innovax has developed a thiomersal-free formulation process change according to the requirement of 2020 Chinese Pharmacopoeia. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the thiomersal-free hepatitis E vaccine compared with the licensed hepatitis E vaccine in people aged ≥16 years.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION:

NCT06564116.

METHODS:

This was a single-center, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study conducted in China. Eligible participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the thiomersal-free hepatitis E vaccine group (HEV-TF group) or the hepatitis E vaccine group (HEV group) stratified by sex and age. Each participant received three doses of the vaccine intramuscularly at 0, 1 and 6 months. Safety was evaluated based on adverse events (AEs) occurred within 30 days following each dose, serious adverse events (SAEs) and pregnancy events occurred during the study period. Immunogenicity was evaluated through quantification of anti-HEV IgG in serum samples collected at 0 and 7 months.

RESULTS:

A total of 612 eligible participants were enrolled and received at least 1 dose of vaccine. 558 participants were included in the per protocol set for immunogenicity. All participants seroconverted in both groups by month 7. The seroconversion rate difference was 0.00 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] -1.38 to 1.34). The geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) in HEV-TF group and HEV group were 16.57 U/mL and 18.47 U/mL, respectively. The GMC ratio was 0.90 (95 % CI 0.79 to 1.01). The overall AEs rates were similar between the groups (16.88 % vs. 12.50 %). Most of AEs were grade 1 or 2. No vaccine-related SAE occurred during the study period.

CONCLUSIONS:

The thiomersal-free hepatitis E vaccine demonstrated non-inferior immunogenicity compared with the licensed hepatitis E vaccine Hecolin® and showed an acceptable safety profile.

39

News (Medical) associated with BTL-TML19 Sep 2025

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) vaccine advisory committee voted on Thursday to rescind an earlier recommendation that allowed parents to choose how to immunise their children against measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (MMRV). However, a childhood vaccination programme within the CDC may still be able to provide and cover the single-shot MMRV vaccine after a subsequent vote from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) muddied the water.The meeting — boycotted by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which has broken ranks with the CDC over COVID-19 recommendations and sued Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. — is the second since Kennedy fired all former ACIP members and handpicked 12 new appointees; five were added to the roster just days earlier (see – Physician Views Results: Docs sound off on ACIP's controversial makeover — and it isn't pretty).It also follows the ouster of former CDC director Susan Monarez, who testified before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions on Wednesday that Kennedy was seeking to reshape the childhood immunisation schedule this month.One shot or twoThe outcome of Thursday's meeting will likely affect how the different measles vaccines are covered by health insurance.Two vaccine options are approved by the FDA: Merck & Co.'s ProQuad MMRV vaccine is designed to provide protection against all four diseases in a single shot, or parents can opt to have their child receive two separate shots, typically given at the same time, with one immunising against MMR and the second against varicella (MMR+V).Under the US childhood immunisation schedule, children receive their first dose of either MMRV or MMR+V between the ages of 12 months and 15 months, and a second dose between the ages of 4 and 6 years old. After concerns emerged in the 2000s that the MMRV vaccine was associated with a higher risk of febrile seizures, ACIP reviewed the safety data on both options. In 2009, ACIP recommended that both vaccines could be given to children, but with a preference for the MMR+V shots as the first dose, and the MMRV vaccine as the second dose. Providers were instructed to discuss the benefits and risks of both vaccination options with parents and caretakers, who were still able to ask for their child's first dose to be the MMRV vaccine, if preferred. According to data presented by the CDC at Thursday's meeting, about 85% of children receive the two-shot MMR+V vaccines, and 15% receive the MMRV vaccine.CDC scientists also shared data demonstrating that the risk of febrile seizure after the first dose of the MMR+V vaccine is about 1 in every 3000 to 4000 doses, while the risk increases two-fold if the MMRV vaccine is given as the first dose. No increased risk was found regarding the second dose. ACIP voted 8-3 to no longer recommend the MMRV vaccine for children under age 4, with one abstention.However, the committee members also voted 8-1, with three abstentions, not to change coverage for the MMRV vaccine under the CDC's Vaccines For Children (VFC) programme — which provides vaccines to children whose parents or guardians may not be able to afford them — though several expressed confusion about what the vote meant and how it would affect childhood vaccinations and insurance coverage.'Déjà vu' discussionThroughout Thursday's meeting, several ACIP members questioned the long-term effects of febrile seizures, including Vicky Pebsworth, Evelyn Griffin and Retsef Levi. They rationalised their objection to the MMRV vaccine as concern over a lack of years of follow-up data that prove the shot is safe. "If we assume that the benefit is long term, I think we also need to consider the fact that some of the adverse impacts could also be long term," Levi said.However, fellow ACIP member Cody Meissner pushed back on that idea, noting that febrile seizures are common in children under five and "pretty well defined," adding that "the vast majority of febrile seizures do not occur in association with vaccines."Similar to how he, at the last ACIP meeting, pointed out that the safety of thimerosal in vaccines had already been addressed, Meissner said the MMRV discussion "is really déjà vu for me because we had extensive discussions on this very topic 15 years ago.""As a paediatrician for more than 30 years, we're so familiar with febrile seizures. And I think most paediatricians would say that the prognosis is excellent," he added.Meissner said he supports the current ACIP recommendations, which allow parents to choose which vaccine they prefer, and voted against restricting the first dose to just the MMR+V vaccine. ACIP member Joseph Hibbeln, who also cast a no vote, characterised the debate as determining which poses a greater risk: "febrile seizures, which may or may not have long-term consequences — likely not — as compared to falling below a 95%, 90% coverage rate for herd immunity." He described the consequences of losing herd immunity as "devastating — pregnant women losing their babies, newborns dying and having congenital rubella syndromes." "If we make a major change…I think we have to have a darn good reason as to why we're making that change," Hibbeln added. Insurance impactsSeveral ACIP liaisons, including representatives of medical and infectious disease organisations, brought up their own concerns with changing the MMRV vaccine recommendation — and criticised what they perceived as a lack of comprehensive information in the CDC's presentation. "You're not looking at all of the aspects of how we evaluate vaccine implementation. You're looking at very small data points and misrepresenting how it works in the real world and how we take care of our patients," said Jason Goldman, president of the American College of Physicians. "So no, this was not a thoroughly vetted discussion. I want to see how we implement it, how it's accepted by the population, what's the feasibility, what's the equity, what are the harms and benefits. You have not considered all of those aspects in this presentation."Robert Hopkins, medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, also pointed out a lack of consideration for issues around equity or "the implications of these decisions for our patients and for the practising physicians who are carrying out these actions."Goldman further decried that a recommendation against the MMRV vaccine gives "license to insurance companies and the [VFC] programme not to cover this vaccine… you are taking away the choice of parents to have informed consent and discussion with their physician on what they want to do for the health and benefit of their children."The implication that children could lose insurance coverage for vaccines is what seemed to have swayed the ACIP's second vote, which allows VFC to continue covering the MMRV shot. Before the vote, Pebsworth asked for clarification on whether the MMRV vaccine could still be given if the group voted against it, and seemed unaware that a recommendation from ACIP would impact insurance coverage. ACIP Chair Martin Kulldorff clarified that "our vote does have consequences sometimes on insurance coverage."Representatives from VFC and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services confirmed that recommending against the MMRV vaccine would have coverage implications. "So that implies that the parents' choice, unless they want to pay for it themselves…is taken away," Hibbeln said. Faced with that knowledge, all members except Kulldorff either abstained or voted to allow VFC to continue covering the MMRV vaccine.

VaccineClinical Study

15 Sep 2025

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's vaccine advisory group meets again Thursday and Friday. Monday, the Department of Health and Human Services revealed five new members.

After Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. overhauled the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) vaccine advisory panel over the summer, replacing 17 of its prior members with seven of his own selections, he's adding to the lineup with five new appointees.New to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are Catherine M. Stein, Ph.D.; Evelyn Griffin, M.D.; Hilary Blackburn; Kirk Milhoan, M.D., Ph.D.; and Raymond Pollak, M.D., according to a notice sent out by the HHS Monday afternoon.The names of the new ACIP members had all been reported two weeks ago, first by Jeremy Faust, M.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, in his Substack blog “Inside Medicine.” Notably, the earlier reporting featured two other potential ACIP members—New Orleans emergency room specialist Joseph Fraiman, M.D., and pediatric neurologist John Gaitanis, M.D.—who aren't included in HHS' announcement. After Faust revealed the list of seven potential ACIP members, news outlets such as Politico took an opportunity to dive into the appointees' history. The publication noted that Milhoan is a senior fellow at the Independent Medical Alliance, which has been fighting to restrict the use of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 in pregnant women and children.Also among the new members, Stein, an epidemiologist and professor at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, in 2022 called for an end to university vaccine mandates. Earlier in the pandemic, she was labeled a "COVID-19 truther" by a local publication for her stance that the government and media were overplaying the seriousness of the threat.Others in the Trump administration made similar remarks during that time span, notably FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, M.D., who in 2023 argued that vaccine mandates "ignored natural immunity."The ACIP reviews in-depth data presentations on new and existing vaccines and votes on usage recommendations for the CDC director to consider. However, amid the leadership turmoil at the CDC and the perceived meddling in vaccine policy by long-time anti-vaccine activist RFK Jr., some states are casting doubt on the new setup and are taking vaccine policy into their own hands.During the revamped panel's first session in June, members voted to ban the vaccine preservative thimerosal in the U.S. Thimerosal has been used to preserve vaccines for decades, but, last year, it was a component in fewer than 5% of flu shots used in the U.S. At this week's ACIP meeting, scheduled for Thursday and Friday, the group will discuss recommendations around vaccines for COVID-19, hepatitis B and measles, mumps and rubella (MMR). This week’s forum will mark the second gathering of the panel since RFK Jr. ousted the prior sitting members and the first for the five new appointees announced Monday.The ACIP panel is scheduled to spend much of Thursday discussing safety data and recommendations for hepatitis B vaccinations at birth before voting on that issue, plus guidance around MMR vaccines, according to a draft meeting agenda (PDF) on the CDC’s website.RFK Jr.-appointed ACIP chair Martin Kulldorff, Ph.D., questioned the widespread practice of inoculating newborn children against hepatitis B in the hospital at the previous meeting of the revamped ACIP in late June.Meanwhile, on Friday, Sept. 19, the panel will focus solely on COVID-19 vaccines before voting on recommendations for the shots, homing in on updated safety and efficacy data as well as current epidemiology trends.

VaccineExecutive Change

26 Aug 2025

iStock,

csraphotography

The MIT professor of management, who already sits on the CDC’s revamped immunization advisory committee, is a known skeptic of vaccines, particularly mRNA technology.

The CDC has appointed established vaccine critic Retsef Levi to lead a COVID-19 committee tasked with reviewing vaccine safety and efficacy data.

According to reporting on Monday from

Reuters

, which confirmed the appointment with a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, Levi will take charge of this COVID-19 immunization working group. This news adds to the

updated terms of reference

published by the CDC on Aug. 20, which stated that agency staffers will not be part of this committee.

The COVID-19 immunization workgroup will function as a subgroup of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), as per the agency’s document. The subcommittee will primarily serve “to review relevant published and unpublished data, and clinical and scientific knowledge” and come up with “options” that it will then present to ACIP during public meetings to help the advisory panel craft vaccination recommendations. Levi is a member of ACIP. Reporting from

Endpoints News

additionally revealed that Levi will work alongside Robert Malone and James Pagano, both of whom also serve on ACIP.

Levi has previously criticized mRNA vaccines, in particular, claiming that they can cause harm and even death, according to

multiple

sources

, and has

called for their withdrawal

from the market—something that could happen “

within months

,” according to recent media reports. Like Levi, Malone also has a well-documented background of

criticizing vaccines

, particularly those using mRNA technology. Pagano is an emergency medicine physician.

As head of the COVID-19 subcommittee, Levi will bring his

experience

from the MIT Sloan School of Management, where he is a professor of operations management. He is also lead faculty for the school’s Food Chain Supply Analytics initiative.

Levi’s vaccine skepticism was on full display during the most recent ACIP meeting in June, when the panel was supposed to—but

ultimately did not

—vote on COVID-19 immunization guidelines. Even when faced with evidence showing that vaccines containing thimerosal are safe, Levi declined to agree. Concluding that they haven’t caused harm, he argued, “

is a tricky issue.

” He added that while evidence indicates individual vaccines containing thimerosal are not harmful, clearly there is harm based on cumulative effects.

Levi was also one of two panelists who voted against recommending Merck’s respiratory syncytial virus antibody Enflonsia for use in infants—a recommendation

ACIP ultimately endorsed

.

Levi found his way onto ACIP this June, when Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

purged

all 17 previous members of the committee, claiming that the “clean sweep” was “necessary to reestablish public confidence in vaccine science.” This move has attracted criticism from many groups, including the American Medical Association, which

called for a Senate probe

into Kennedy and for an “immediate reversal” of his decision.

“Vaccines have been proven to dramatically reduce hospitalization and death,” according to an AMA resolution days after Kennedy emptied the ACIP. “It is imperative for recommendations to be made without political interference.”

VaccineExecutive ChangemRNA

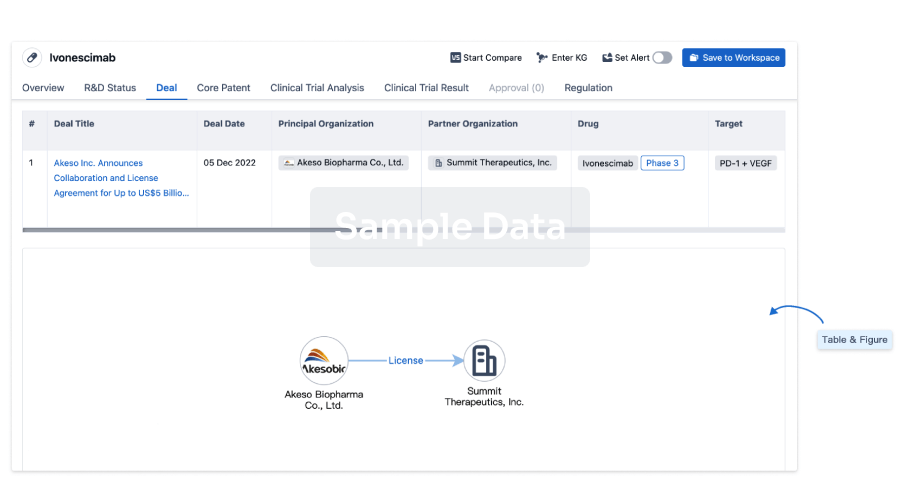

100 Deals associated with BTL-TML

Login to view more data

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza, Human | Phase 2 | United States | 05 Aug 2020 | |

| COVID-19 | Phase 2 | United States | 30 Jul 2020 | |

| Herpes Labialis | Phase 2 | United States | 01 Jul 2013 | |

| Stomatitis, Herpetic | Phase 2 | United States | 01 Jul 2013 |

Login to view more data

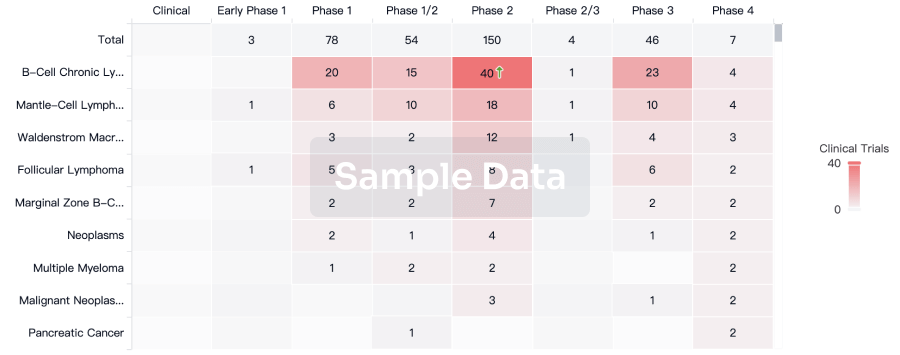

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

Phase 2 | 303 | Matching Placebo | dxrsrjbick = ofcvnndeax paekvrzngg (zzghuxmfei, oexptoykzu - zqrvutflzg) View more | - | 14 Mar 2016 |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free