BRONX, N.Y., May 8, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Researchers at the National Cancer Institute-designated Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center (MECCC) have shown that a breakthrough therapy for treating blood cancers can be adapted to treat solid tumors—an advance that could transform cancer treatment. The promising findings, reported today in Science Advances, involve CAR-T cell therapy, which supercharges the immune system to identify and attack cancer cells.

Continue Reading

Xingxing Zang, Ph.D.

"CAR-T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma but hasn't worked well against solid tumors," said Xingxing Zang, Ph.D., the paper's senior author. "We found that our changes to standard CAR-T cell therapy can significantly boost its effectiveness against solid tumors, including often-fatal pancreatic cancer and glioblastomas." Dr. Zang is a member of MECCC Cancer Therapeutics Research Program and professor of microbiology & immunology, of oncology, of medicine, and of urology, the Louis Goldstein Swan Chair in Cancer Research and the founding director of MECCC's Institute for Immunotherapy of Cancer at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The first author of the paper is Christopher Nishimura, an M.D./Ph.D. student in Dr. Zang's lab.

Developing Personalized Cancer Killers

Dr. Zang and his colleagues created five CAR-T therapies that they tested on mice implanted with several types of solid human tumors. One of the therapies—which used two novel components—proved superior in safely and effectively shrinking not only glioblastoma and pancreatic tumors but lung cancer tumors as well.

CAR-T cell therapy, short for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, is a marvel of genetic engineering that transforms T cells (a type of immune cell) into cancer-seeking missiles programmed to attack on contact. The therapy involves extracting the patient's own T cells and equipping them with a single gene that codes for several different proteins. ("Chimeric" comes from the Chimera of Greek mythology with its lion's head, goat's body, and serpent's tail.) The genetically modified T cells are allowed to multiply and are then infused back into the patient.

Their specially designed gene enables the infused T cells to express synthetic CAR receptors on their surface. The CARs can recognize specific proteins, known as antigens, that protrude from cancer cells. Thanks to their new CARs, the T cells are able to home in on cancer cells and then switch to attack mode.

CARs contain four key proteins, and Dr. Zang and his colleagues achieved success against solid tumors by altering two of them. (See illustration of CAR-T cell receptor below.)

Five CAR-Ts Confront Three Types of Cancer

All five CAR-T therapies developed by the Zang team used the same novel targeting protein: a monoclonal antibody that binds to B7-H3, a cancer-cell antigen widely expressed on most solid tumors and their blood vessels. Dr. Zang had previously helped to discover that B7-H3 allows tumors to evade immune attack by interfering with T cells.

"We wanted our CARs to not only attach T cells to solid tumors but also—by binding specifically to B7-H3—to prevent B7-H3 from interfering with the T cells' ability to attack and destroy cancer cells and their blood vessels," said Dr. Zang.

Simply attaching CAR-T cells to tumor cells isn't enough to kill them. CARs must also include a costimulatory protein to help activate T cells once they've made contact with cancer cells. Four of the five CAR-T cell therapies developed by Dr. Zang's lab used previously deployed costimulatory proteins. But their fifth therapy used a protein never before tried in CAR-T cell therapy. In 2015, Dr. Zang discovered that T cells possess a receptor he called TMIGD2 that activates T cells when stimulated. He later realized that incorporating TMIGD2 into CAR-T cells might enable them to overcome the challenges posed by solid tumors.

"Factors such as low-oxygen levels and immune checkpoints inside solid tumors make for a hostile microenvironment that can strongly suppress immune attack by T cells—which also have trouble penetrating solid tumors' dense connective tissue network," Dr. Zang said. "It seemed possible that using TMIGD2 as a costimulatory protein could give CAR-T cells the activation boost they need to reach cancer cells and persist within solid tumors."

These novel CAR-T therapies were tested on mice bearing three solid human tumors: pancreatic, lung, and glioblastoma. All were equally likely to bind their T cells to cancer cells, since their CARs all possessed the same novel antibody aimed at the B7-H3 antigen. The most effective one possessed both the novel antibody and the TMIGD2 protein—a CAR that Dr. Zang calls a TMIGD2 Optimized Potent/Persistent (TOP) CAR.

The TOP Choice

The CAR-T therapy with TOP CAR proved best at keeping mice with pancreatic, lung, and glioblastoma tumors alive. For example, TOP CAR treatment enabled 7 out of 9 mice with glioblastoma tumors to survive, compared with a maximum survival of 3 out of 9 mice achieved by any of the other CAR-T therapies. It was also superior with respect to key effectiveness and safety parameters.

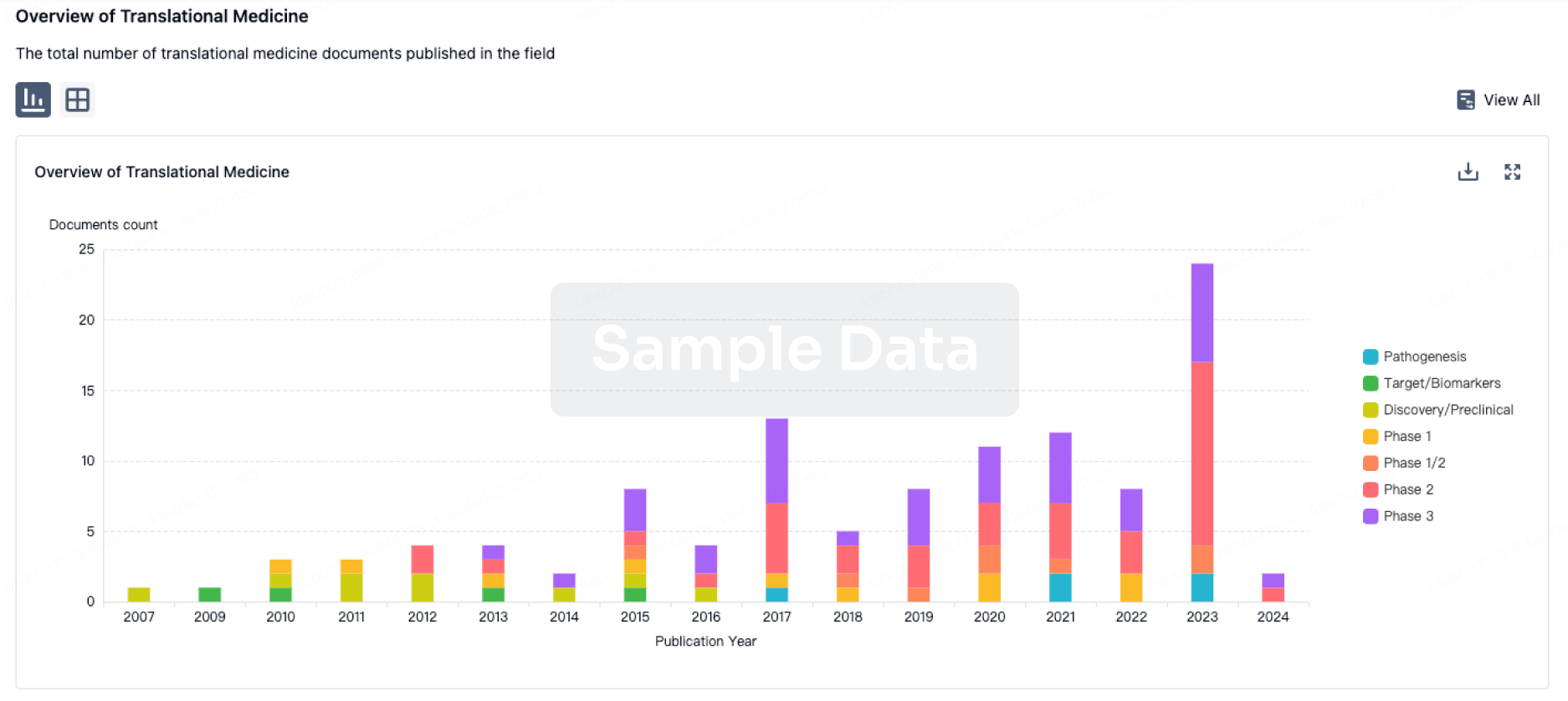

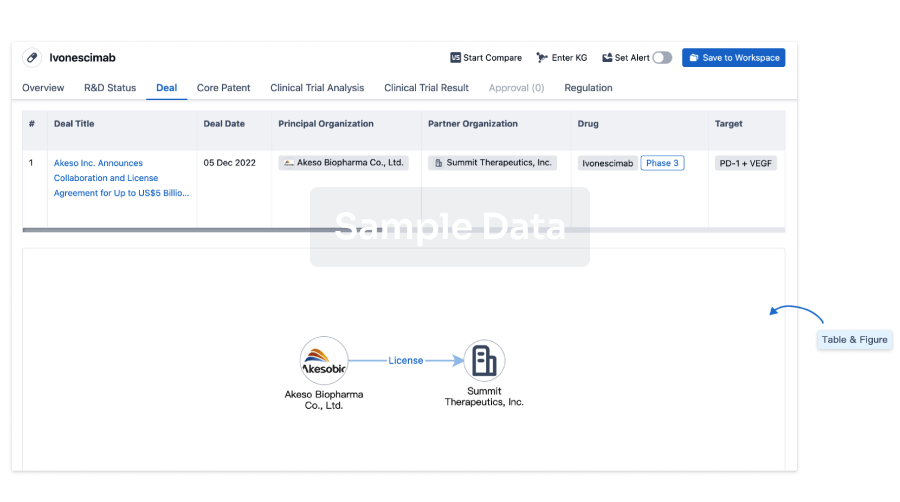

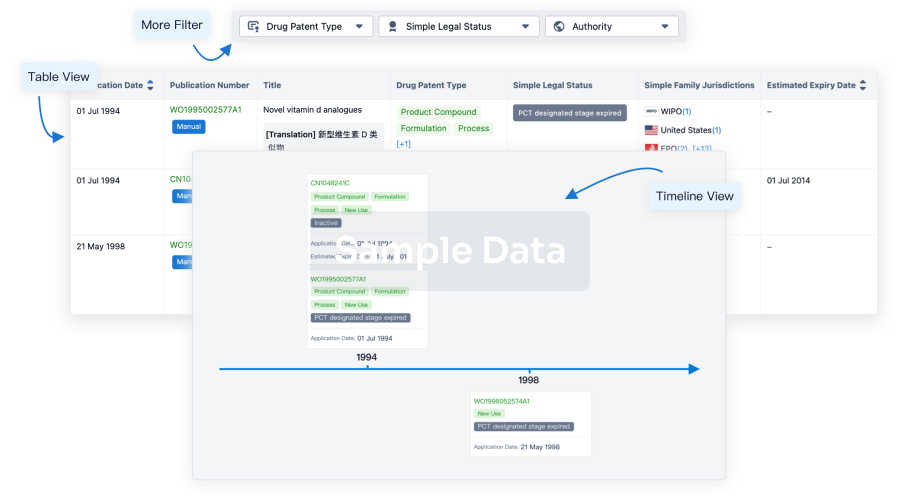

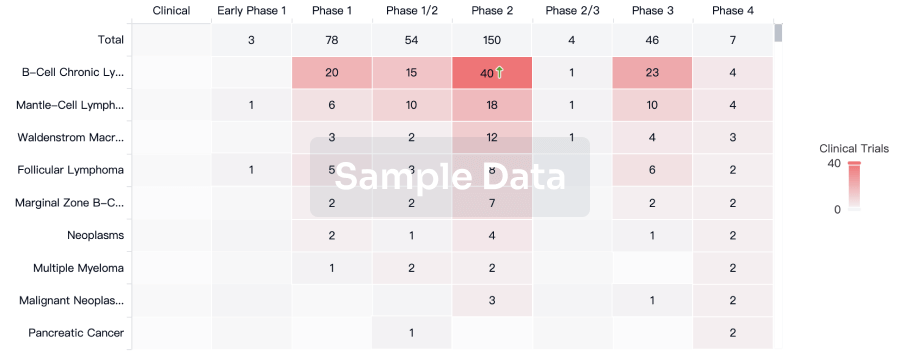

Dr. Zang plans to further develop TOP CAR into an "off-the shelf" platform that can simultaneously target B7-H3 as well as other tumor antigens and can readily be tailored for treating many different types of solid tumors. Einstein has intellectual property protection for a portfolio of Dr. Zang's research and is interested in securing commercial partners to help to move his novel TOP CAR therapy into clinical trials in the near future, including for cancer of the brain, liver, pancreas, ovary, prostate, lung, bladder, colon, and others. Over the past several years, Dr. Zang has developed two other anti-cancer drugs that are being evaluated in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials in the United States and other countries.

The paper is titled "TOP CAR with TMIGD2 as a safe and effective costimulatory domain in CAR cells treating human solid tumors." Other Einstein authors are Devin Corrigan, M.S., Xiang Yu Zheng, B.S., Phillip M. Galbo Jr., Ph.D., Shan Wang, M.D., Yao Liu, Ph.D., Yau Wei, M.D., Linna Suo, M.D.,Wei Cui, Ph.D. and Deyou Zheng, Ph.D. Other authors are Nadia Mercado, Sc.M., of Brown University School of Public Health and Cheng Cheng Zhang, Ph.D., of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Dr. Zang and Mr. Nishimura are inventors of two pending patents: Chimeric antigen receptors comprising a TMIGD2 costimulatory domain and associated methods of using the same; and Chimeric antigen receptors targeting B7-H3 (CD276) and associated methods. Dr. Zang is an inventor of a pending patent: Monoclonal antibodies against IgV domain of B7-H3 and uses thereof. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Montefiore Einstein Cancer Center

Montefiore Einstein Cancer Center (MECC) is a national leader in cancer research and care located in the ethnically diverse and economically disadvantaged borough of the Bronx, N.Y. MECC combines the exceptional science of Albert Einstein College of Medicine with the multidisciplinary and team-based approach to cancer care of Montefiore Health System. Founded in 1971 and a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Cancer Center since 1972, MECC is redefining excellence in cancer research, clinical care, education and training, and community outreach and engagement. Its mission is to reduce the burden of cancer for all, especially people from historically marginalized communities.

SOURCE Montefiore Einstein Cancer Center