Request Demo

Last update 28 Oct 2025

VNRX-9945

Last update 28 Oct 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms VNRX 9945 |

Target |

Action inhibitors |

Mechanism HBV core protein inhibitors |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization |

Inactive Organization- |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC23H28FN3O4 |

InChIKeyDKPLCDXCFJGTIM-WOVMCDHWSA-N |

CAS Registry2396680-45-6 |

Related

1

Clinical Trials associated with VNRX-9945NCT04845321

Phase 1 Study to Evaluate the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Single and Multiple Ascending Doses of VNRX-9945 in Healthy Adult Volunteers

This is a 2-part first-in-human dose-ranging study to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of escalating doses of VNRX-9945.

Start Date23 Jun 2021 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with VNRX-9945

Login to view more data

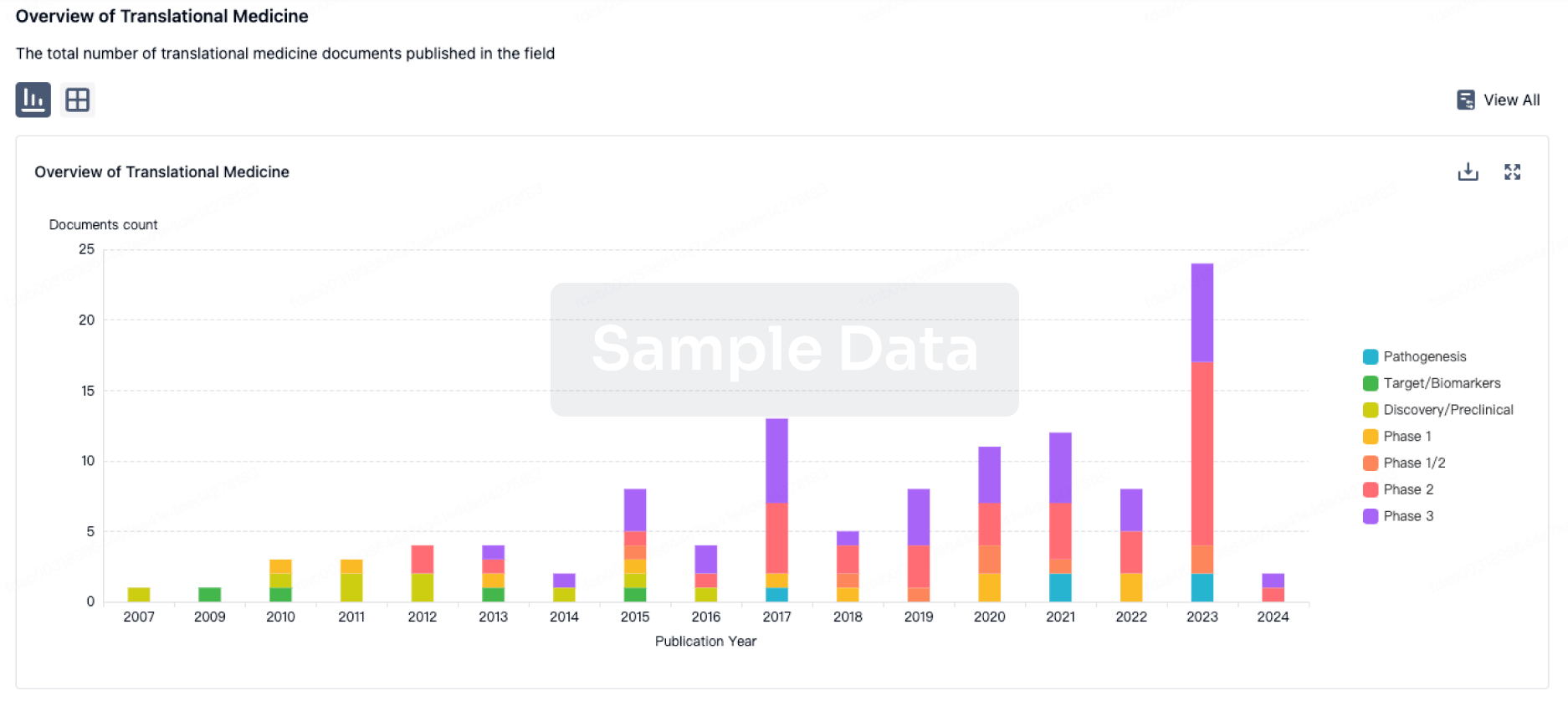

100 Translational Medicine associated with VNRX-9945

Login to view more data

100 Patents (Medical) associated with VNRX-9945

Login to view more data

1

Literatures (Medical) associated with VNRX-994510 Jul 2025·ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters

Discovery of VNRX-9945, a Potent, Broadly Active Capsid Assembly Modulator as a Clinical Candidate for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection

Article

Author: Suto, Robert K. ; White, Andre ; Haimowitz, Thomas ; Benetatos, Christopher A. ; Liu, Bin ; Yao, Jiangchao ; Cakici, Ozgur ; Condon, Stephen M. ; Boyd, Steven A. ; Hart, Susan G. Emeigh ; Coburn, Glen A. ; Burns, Christopher J. ; Lakshminarasimhan, Damodharan ; Pevear, Daniel C. ; Drager, Anthony S.

Targeting the capsid protein of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) has emerged as a promising strategy for developing new antiviral therapies. In this study, we report the discovery of a novel series of pyrrole oxo-carboxamide compounds as HBV capsid assembly modulators (CAMs) that block viral replication. Through a process of focused structure-activity relationship (SAR) optimization, we identified compound 12 (VNRX-9945), which exhibited excellent and broad antiviral activity against multiple HBV genotypes in vitro, along with favorable pharmacokinetic profiles across multiple species. Additionally, 12 demonstrated robust efficacy in the adeno-associated virus mouse model of HBV (AAV-HBV) infection. This compound has advanced into Phase 1 clinical trials to evaluate its safety and pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers, to enable treatment of chronic HBV infections.

4

News (Medical) associated with VNRX-994514 Oct 2021

Venatorx President and CEO Christopher J. Burns, Ph.D./Courtesy Venatorx Pharmaceuticals

On an annual basis in the U.S., at least 2.8 million people have an antibiotic-resistant infection, and more than 35,000 people die from those infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug-resistant pathogens have helped create an antibiotic-resistance crisis. Those magic bullets – antibiotics – aren’t as resilient as they used to be.

A Critical Lack of Funding

Compounding the problem, many pharmaceutical companies have exited the antibiotic business because financial incentive is lacking. Essentially, less private investment and innovation in the development of new antibiotics are impeding efforts to combat drug-resistant infections.

To help rectify this problem, Malvern, PA-based Venatorx Pharmaceuticals, a clinical-stage pharmaceutical company, is developing treatments for patients with multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections.

“Making a new drug to treat a bacteria has historically been very difficult. Bacteria are living organisms. They’ve been around for billions of years. They’ve learned how to fight off an attack from just about any front. Bacteria are clever; you can put them under pressure with an antibiotic, but eventually, they’ll find a way to circumvent it and decrease its effectiveness,” said Venatorx President and CEO Christopher J. Burns, Ph.D. in an email. “There’s an inevitability to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is why every 15 to 20 years, the world needs a new wave of antibiotics. Without them infections are becoming harder, and inevitably impossible, to treat.”

All of the company’s therapeutic candidates were discovered internally, according to Venatorx. Its most advanced development-stage product is taniborbactam, an injectable beta-lactamase inhibitor (BLI). Beta-lactamase inhibitors block the activity of beta-lactamase enzymes and keep beta-lactam antibiotics from degrading.

Venatorx executives believe that taniborbactam, in combination with cefepime, the fourth generation cephalosporin, could provide a broad-spectrum treatment option to meet unmet medical needs in patients with infections caused by carbapenem-resistant pathogens, including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA); suspected polymicrobial infections caused by both gram-negative and gram-positive susceptible pathogens; and engineerable bioterror pathogens, such as Burkholderia.

Venatorx is currently enrolling a Phase III clinical trial of cefepime-taniborbactam in patients with complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs). The trial will assess the safety and efficacy of cefepime-taniborbactam compared with meropenem (another antibiotic) in adults with cUTI, including acute pyelonephritis.

Cefepime-taniborbactam is also under development for the treatment of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (HABP/VABP).

Venatorx’s second development-stage product is VNRX-7145, an orally bioavailable BLI that, in combination with the third generation orally bioavailable cephalosporin, ceftibuten, has the potential to protect the partner antibiotic against extended spectrum beta-lactamases and key CRE – including those expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase and Oxacillinase carbapenemases.

The candidate is intended to treat patients with infections caused by MDR gram-negative pathogens that are resistant to current standard-of-care oral and intravenous antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins and carbapenems.

In July, Venatorx announced positive top line results for its Phase I single ascending dose (SAD) and multiple ascending dose (MAD) clinical trial of VNRX-7145. The Phase I study was a two-part, first-in-human dose-ranging study intended to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of escalating oral doses of the drug.

In part one, subjects received single ascending doses of VNRX-7145. In part two, subjects received multiple escalating doses of VNRX-7145 for 10 days. There were no serious adverse events, and VNRX-7145 was well-tolerated up to the highest single or multiple doses administered, the company said. VNRX-7145 had excellent oral bioavailability, dose-proportional pharmacokinetics across the doses studied and readily achieved efficacy exposure targets identified in non-clinical studies.

Venatorx is continuing the development of VNRX-7145 with a Phase I drug-drug interaction study, which will provide an initial assessment of the safety and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple doses of VNRX-7145 and ceftibuten, when co-administered. Top line results are expected during the fourth quarter of 2021.

Hope for Hepatitis B Sufferers

On another front, more than 250 million individuals chronically infected with chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) worldwide are at risk from complications due to liver disease and liver cancer. Venatorx is developing VNRX-9945, a core protein allosteric modulator (CpAM), for the treatment of chronic HBV infection.

VNRX-9945 is a third-generation, highly potent dual-mechanism viral replication inhibitor with activity against both nucleocapsid assembly and formation of cccDNA. In preclinical studies, it demonstrated broad antiviral activity against multiple HBV genotypes in vitro and suppresses HBV DNA to below the lower limit of qualification in a mouse model of HBV infection.

In late June, Venatorx announced that the first patient was dosed in a Phase I clinical trial evaluating VNRX-9945, which will evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple ascending doses of VNRX-9945, administered orally in healthy adult volunteers.

“Current front-line therapies only partially suppress HBV replication, are not curative and require therapy for an indefinite duration, adding to patient burden,” explained Burns. “Novel inhibitors of HBV are required to further suppress viral replication and provide the conditions required to achieve immune control, termed a ‘functional cure’.”

Concurrently, Venatorx is developing a novel class of non-beta-lactam molecules that kill bacteria by the same selective mechanism as beta-lactams, blocking cell wall synthesis via binding to the bacterial penicillin binding proteins (PBPs). These new molecules have been designed to be impervious to degradation by any beta-lactamases.

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is ranked as a “Priority 1: Critical” carbapenem resistant pathogen on the World Health Organization’s list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. A. baumannii is primarily associated with hospital-acquired infections and has become resistant to a large number of antibiotics, including carbapenems and third generation cephalosporins – the best-known available antibiotics for treating MDR bacteria.

In 2020, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases awarded Venatorx $3.2 million to advance its novel series of PBP Inhibitors targeting MDR A. baumannii through Phase I clinical testing. There is the potential to receive up to $44.2 million, if all project milestones are met.

Venatorx also is developing an oral penicillin-binding protein inhibitor (PBPi) to address the growing problem of resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae to the last resort antibiotic for outpatient use, ceftriaxone. Venatorx has identified non-beta-lactam transpeptidase inhibitors that are rapidly bactericidal, impervious to beta-lactamases, and show promising selective activity against gonococci, including both wild-type strains and isolates with PBP variants that confer ceftriaxone resistance.

In 2019, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) awarded Venatorx up to $4.1 million in non-dilutive funding, with the possibility of up to an additional $8.9 million if certain project milestones are met. CARB-X funding will help Venatorx progress these early molecules from hit-to-lead through IND-enabling studies.

“Normally an unmet medical need is confronted by big pharma,” noted Burns. “But for antibiotics specifically, today's reimbursement rates effectively penalize physicians and hospitals for prescribing newer, more advanced antibiotics. Thus, pharma sees that the revenue and profit from investing 5 to 10 years to develop a new antibiotic will not yield a return on the investment, and have largely moved to the sidelines.

Fixing a Broken Economic Model

“An improved economic model is needed,” he continued, “one that incentivizes and supports antibiotic innovation and ensures that medicines are available when needed and new drugs are constantly in the pipeline.

Burns highlighted two proposed remedies.

“There are two obvious solutions that policymakers could implement with the stroke of a pen,” he said. “Pass the PASTEUR Act, a government subscription plan that incentivizes and rewards the small innovative biotech companies for investing years of blood, sweat and tears to solve this societal problem; and pass the DISARM Act (Developing an Innovative Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistant Microorganisms Act) or an equivalent, that removes the economic noose from around the neck of physicians and hospitals when they want to prescribe a life-saving new antibiotic but are currently dissuaded.”

13 Oct 2021

Less private investment and innovation in the development of new antibiotics are impeding efforts to combat drug-resistant infections.

Venatorx President and CEO Christopher J. Burns, Ph.D./Courtesy Venatorx Pharmaceuticals

On an annual basis in the U.S., at least

2.8 million

people have an antibiotic-resistant infection, and more than 35,000 people die from those infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug-resistant pathogens have helped create an antibiotic-resistance crisis. Those magic bullets – antibiotics – aren’t as resilient as they used to be.

A Critical Lack of Funding

Compounding the problem, many pharmaceutical companies have exited the antibiotic business because financial incentive is lacking. Essentially,

less private investment

and innovation in the development of new antibiotics are impeding efforts to combat drug-resistant infections.

To help rectify this problem, Malvern, PA-based

Venatorx Pharmaceuticals,

a clinical-stage pharmaceutical company, is developing treatments for patients with multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections.

“Making a new drug to treat a bacteria has historically been very difficult. Bacteria are living organisms. They’ve been around for billions of years. They’ve learned how to fight off an attack from just about any front. Bacteria are clever; you can put them under pressure with an antibiotic, but eventually, they’ll find a way to circumvent it and decrease its effectiveness,” said Venatorx President and CEO Christopher J. Burns, Ph.D. in an email. “There’s an inevitability to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is why every 15 to 20 years, the world needs a new wave of antibiotics. Without them infections are becoming harder, and inevitably impossible, to treat.”

All of the company’s therapeutic candidates were discovered internally, according to Venatorx. Its most advanced development-stage product is taniborbactam, an injectable beta-lactamase inhibitor (BLI). Beta-lactamase inhibitors block the activity of beta-lactamase enzymes and keep beta-lactam antibiotics from degrading.

Venatorx executives believe that taniborbactam, in combination with cefepime, the fourth generation cephalosporin, could provide a broad-spectrum treatment option to meet unmet medical needs in patients with infections caused by carbapenem-resistant pathogens, including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA); suspected polymicrobial infections caused by both gram-negative and gram-positive susceptible pathogens; and engineerable bioterror pathogens, such as Burkholderia.

Venatorx is currently enrolling a Phase III clinical trial of cefepime-taniborbactam in patients with complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs). The trial will assess the safety and efficacy of cefepime-taniborbactam compared with meropenem (another antibiotic) in adults with cUTI, including acute pyelonephritis.

Cefepime-taniborbactam is also under development for the treatment of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (HABP/VABP).

Venatorx’s second development-stage product is VNRX-7145, an orally bioavailable BLI that, in combination with the third generation orally bioavailable cephalosporin, ceftibuten, has the potential to protect the partner antibiotic against extended spectrum beta-lactamases and key CRE – including those expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase and Oxacillinase carbapenemases.

The candidate is intended to treat patients with infections caused by MDR gram-negative pathogens that are resistant to current standard-of-care oral and intravenous antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins and carbapenems.

In July, Venatorx

announced

positive top line results for its Phase I single ascending dose (SAD) and multiple ascending dose (MAD) clinical trial of VNRX-7145. The Phase I study was a two-part, first-in-human dose-ranging study intended to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of escalating oral doses of the drug.

In part one, subjects received single ascending doses of VNRX-7145. In part two, subjects received multiple escalating doses of VNRX-7145 for 10 days. There were no serious adverse events, and VNRX-7145 was well-tolerated up to the highest single or multiple doses administered, the company said. VNRX-7145 had excellent oral bioavailability, dose-proportional pharmacokinetics across the doses studied and readily achieved efficacy exposure targets identified in non-clinical studies.

Venatorx is continuing the development of VNRX-7145 with a Phase I drug-drug interaction study, which will provide an initial assessment of the safety and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple doses of VNRX-7145 and ceftibuten, when co-administered. Top line results are expected during the fourth quarter of 2021.

Hope for Hepatitis B Sufferers

On another front, more than 250 million individuals chronically infected with chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) worldwide are at risk from complications due to liver disease and liver cancer. Venatorx is developing VNRX-9945, a core protein allosteric modulator (CpAM), for the treatment of chronic HBV infection.

VNRX-9945 is a third-generation, highly potent dual-mechanism viral replication inhibitor with activity against both nucleocapsid assembly and formation of cccDNA. In preclinical studies, it demonstrated broad antiviral activity against multiple HBV genotypes in vitro and suppresses HBV DNA to below the lower limit of qualification in a mouse model of HBV infection.

In late June, Venatorx

announced

that the first patient was dosed in a Phase I clinical trial evaluating VNRX-9945, which will evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple ascending doses of VNRX-9945, administered orally in healthy adult volunteers.

“Current front-line therapies only partially suppress HBV replication, are not curative and require therapy for an indefinite duration, adding to patient burden,” explained Burns. “Novel inhibitors of HBV are required to further suppress viral replication and provide the conditions required to achieve immune control, termed a ‘functional cure’.”

Concurrently, Venatorx is developing a novel class of non-beta-lactam molecules that kill bacteria by the same selective mechanism as beta-lactams, blocking cell wall synthesis via binding to the bacterial penicillin binding proteins (PBPs). These new molecules have been designed to be impervious to degradation by any beta-lactamases.

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is ranked as a “Priority 1: Critical” carbapenem resistant pathogen on the World Health Organization’s list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. A. baumannii is primarily associated with hospital-acquired infections and has become resistant to a large number of antibiotics, including carbapenems and third generation cephalosporins – the best-known available antibiotics for treating MDR bacteria.

In 2020, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases awarded Venatorx $3.2 million to advance its novel series of PBP Inhibitors targeting MDR A. baumannii through Phase I clinical testing. There is the potential to receive

up to $44.2 million

, if all project milestones are met.

Venatorx also is developing an oral penicillin-binding protein inhibitor (PBPi) to address the growing problem of resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae to the last resort antibiotic for outpatient use, ceftriaxone. Venatorx has identified non-beta-lactam transpeptidase inhibitors that are rapidly bactericidal, impervious to beta-lactamases, and show promising selective activity against gonococci, including both wild-type strains and isolates with PBP variants that confer ceftriaxone resistance.

In 2019, the

Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator

(CARB-X) awarded Venatorx up to $4.1 million in non-dilutive funding, with the possibility of up to an additional $8.9 million if certain project milestones are met. CARB-X funding will help Venatorx progress these early molecules from hit-to-lead through IND-enabling studies.

“Normally an unmet medical need is confronted by big pharma,” noted Burns. “But for antibiotics specifically, today’s reimbursement rates effectively penalize physicians and hospitals for prescribing newer, more advanced antibiotics. Thus, pharma sees that the revenue and profit from investing 5 to 10 years to develop a new antibiotic will not yield a return on the investment, and have largely moved to the sidelines.

Fixing a Broken Economic Model

“An improved economic model is needed,” he continued, “one that incentivizes and supports antibiotic innovation and ensures that medicines are available when needed and new drugs are constantly in the pipeline.

Burns highlighted two proposed remedies.

“There are two obvious solutions that policymakers could implement with the stroke of a pen,” he said. “Pass the

PASTEUR Act

, a government subscription plan that incentivizes and rewards the small innovative biotech companies for investing years of blood, sweat and tears to solve this societal problem; and pass the DISARM Act (Developing an Innovative Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistant Microorganisms Act) or an equivalent, that removes the economic noose from around the neck of physicians and hospitals when they want to prescribe a life-saving new antibiotic but are currently dissuaded.”

Phase 1Clinical ResultPhase 3

27 Sep 2021

MALVERN, Pa.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Venatorx Pharmaceuticals today announced that the Company, along with its collaborators, will present seven posters and two oral abstracts at IDWeek 2021, which is taking place virtually September 29 – October 3, 2021.

Session A1. Novel Antimicrobial Agents

Oral Presentation #133 – ARGONAUT-III: Susceptibility of Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiellae to Cefepime-Taniborbactam. A.R. Mack, C. Bethel, S. Marshall, R. Patel, D. van Duin, V.G. Fowler, D.D. Rhoads, M. Jacobs, F. van den Akker, D.A. Six, G. Moeck, K.M. Papp-Wallace, R.A. Bonomo.

Poster Presentation #1055 – ARGONAUT-IV: Susceptibility of Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiellae to Ceftibuten/VNRX-5236. A.R. Mack, C. Bethel, S. Marshall, R. Patel, D. van Duin, V.G. Fowler, D.D. Rhoads, M. Jacobs, F. van den Akker, D.A. Six, G. Moeck, K.M. Papp-Wallace, R.A. Bonomo.

Poster Presentation #1063 – ARGONAUT-V: Susceptibility of Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Cefepime-Taniborbactam. A.R. Mack, C. Bethel, S. Marshall, R. Patel, D. van Duin, V.G. Fowler, D.D. Rhoads, M. Jacobs, F. van den Akker, D.A. Six, G. Moeck, K.M. Papp-Wallace, R.A. Bonomo.

Session A3. Resistance Mechanisms

Poster Presentation #1286 – Taniborbactam Inhibits Cefepime-Hydrolyzing Variants of Pseudomonas-derived Cephalosporinase (PDC). A.R. Mack, C. Bethel, M.A. Taracilla, F. van den Akker, B.A. Miller, T. Uehara, D.A. Six, K.M. Papp-Wallace, R.A. Bonomo.

Session A4. Treatment of antimicrobial resistant infections

Oral Presentation #203 – Activity of Cefepime in Combination with Taniborbactam (formerly VNRX-5133) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a Global 2018-2020 Surveillance Collection. M. Hackel, M.G. Wise, D.F. Sahm.

Poster Presentation #1253 – Antimicrobial Activity of Cefepime in Combination with Taniborbactam (formerly VNRX-5133) Against Clinical Isolates of Enterobacterales from 2018-2020 Global Surveillance. M. Hackel, M.G. Wise, D.F. Sahm.

Poster Presentation #1293 – In vitro Activity of Ceftibuten in Combination with VNRX-5236 against Clinical Isolates of Enterobacterales from Urinary Tract Infections Collected in 2018-2020. M. Hackel, M.G. Wise, D.F. Sahm.

Session D1. Diagnostics: Bacteriology/mycobacteriology

Poster Presentation #642 – Facility reported vs. CLSI MIC breakpoint comparison of Carbapenem non-susceptible (Carb-NS) Enterobacteriaceae (ENT) from 2016-2019: A multicenter evaluation. V. Gupta, K. Yu, J.M. Pogue, C.J. Clancy.

Session N10. Healthcare-Associated Infections: Gram-Negatives (MDR-GNR)

Poster Presentation #786 – Facility reported vs. CLSI MIC breakpoint comparison of Carbapenem non-susceptible (Carb-NS) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PSA) from 2016-2019: A multicenter evaluation. V. Gupta, K. Yu, J.M. Pogue, J. Weeks, C.J. Clancy.

About Venatorx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Founded in 2010, Venatorx Pharmaceuticals is a private, clinical-stage pharmaceutical company focused on improving health outcomes for patients with multi-drug-resistant bacterial infections and hard-to-treat viral infections. Venatorx has built a world-class in-house research and development organization that has filed over 120 patents. Venatorx’s two lead antibacterial clinical-stage programs are intravenous (cefepime-taniborbactam) and oral (ceftibuten/VNRX-7145) broad-spectrum beta-lactam / beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations that are in Phase 3 and Phase 1, respectively. In addition, the first Venatorx antiviral compound (VNRX-9945), a Hepatitis B virus inhibitor, is in Phase 1 clinical development. The Company also has discovery-stage programs targeting a novel class of non-beta-lactam antibiotics called Penicillin Binding Protein (PBP) inhibitors that have the potential to circumvent 70+ years of resistance and usher in a new wave of antibacterial therapeutics. For more information about Venatorx, please visit .

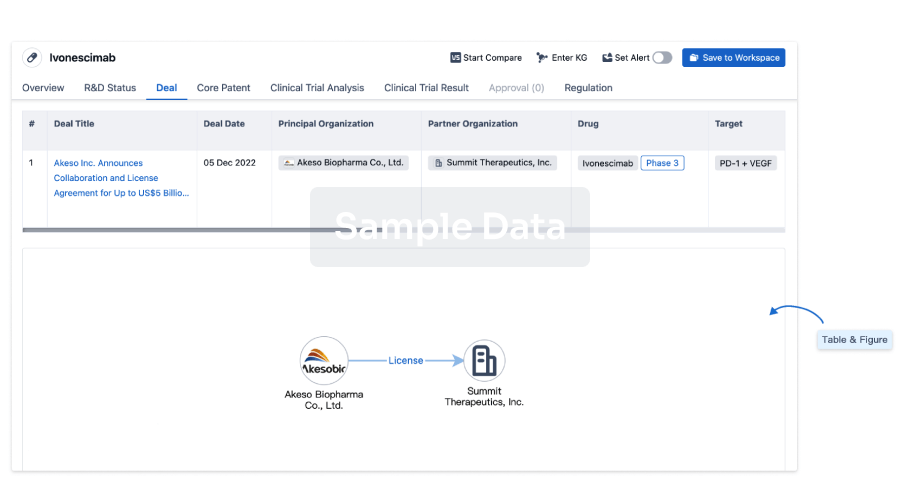

100 Deals associated with VNRX-9945

Login to view more data

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B, Chronic | Preclinical | United States | 23 Jun 2021 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

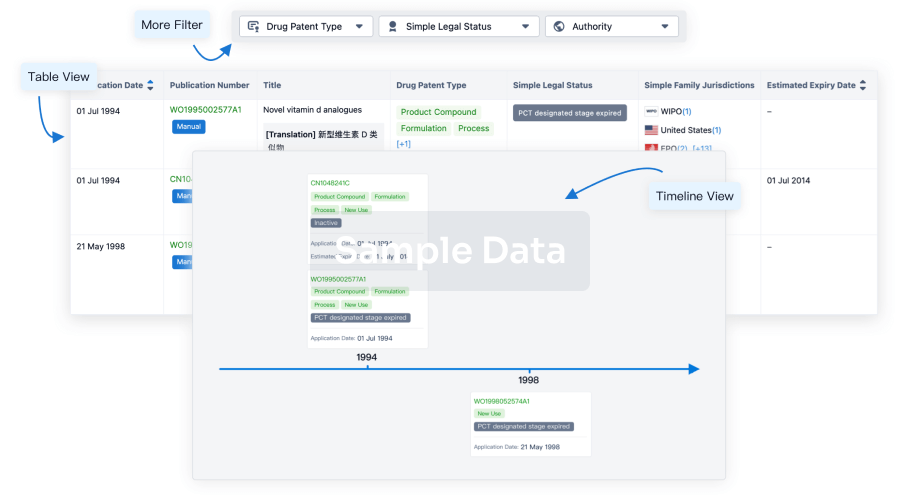

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

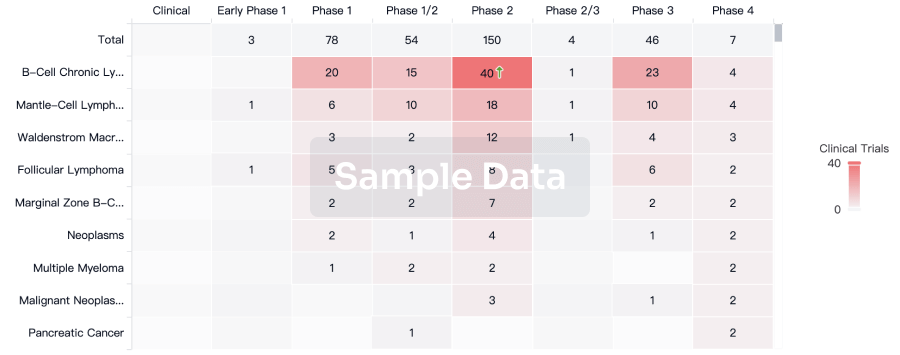

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free