Request Demo

Last update 29 Jul 2025

Adjuvanted plague vaccine(Dynavax Technologies Corporation/United States Department of Defense)

Last update 29 Jul 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Prophylactic vaccine |

Synonyms Recombinant plague vaccine adjuvanted with CpG 1018, DV2-PLG-01 |

Target- |

Action stimulants |

Mechanism Immunostimulants |

Therapeutic Areas- |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication- |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization- |

Inactive Organization- |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest Phase- |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Adjuvanted plague vaccine(Dynavax Technologies Corporation/United States Department of Defense)

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Adjuvanted plague vaccine(Dynavax Technologies Corporation/United States Department of Defense)

Login to view more data

100 Patents (Medical) associated with Adjuvanted plague vaccine(Dynavax Technologies Corporation/United States Department of Defense)

Login to view more data

1

News (Medical) associated with Adjuvanted plague vaccine(Dynavax Technologies Corporation/United States Department of Defense)03 Aug 2023

Generated record quarterly HEPLISAV-B® vaccine net product revenue of $56 million, a 73% year-over-year increase

Full year HEPLISAV-B net product revenue guidance raised to $200 - $215 million, compared to prior range of $165 - $185 million

Cash and investments increased to $682 million at quarter end; expects positive free cash flow for full year

Conference call today at 4:30 p.m. ET/1:30 p.m. PT

EMERYVILLE, Calif., Aug. 3, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- Dynavax Technologies Corporation (Nasdaq: DVAX), a commercial-stage biopharmaceutical company developing and commercializing innovative vaccines, today reported financial results and provided a business update for the quarter ended June 30, 2023.

"This quarter's impressive HEPLISAV-B revenue growth reflects the continued expansion of the hepatitis B vaccine market and our team's success in capturing market share. As a result of the strong HEPLISAV-B performance in the first half of 2023, which exceeded expectations, and the growing enthusiasm that we see in the market, we are significantly raising our revenue expectations for the full year," said Ryan Spencer, Chief Executive Officer of Dynavax.

BUSINESS UPDATES

HEPLISAV-B® [Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant), Adjuvanted]

HEPLISAV-B vaccine is the first and only adult hepatitis B vaccine approved in the U.S., the European Union and Great Britain that enables series completion with only two doses in one month. Hepatitis B vaccination is universally recommended for adults aged 19-59 in the U.S.

HEPLISAV-B achieved net product revenue of $56.4 million for the second quarter of 2023, an increase of 73% compared to $32.7 million for the second quarter of 2022.

HEPLISAV-B total market share increased to approximately 39%, compared to approximately 32% at the end of the second quarter of 2022.

HEPLISAV-B market share in the Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs) and Clinics segment was approximately 53% at the end of the second quarter of 2023, compared to approximately 39% for the same quarter in 2022.

HEPLISAV-B maintained a strong market share of 45% in the retail segment at the end of the second quarter of 2023, compared to 46% for the same quarter in 2022.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently accepted the supplemental Biologics License Application (sBLA) for HEPLISAV-B vaccination of adults on hemodialysis with a Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) action date of May 13, 2024.

Driven by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee of Immunization Practices (ACIP) universal recommendation for adult hepatitis B vaccination, Dynavax continues to see the expansion of the hepatitis B vaccine market and believes HEPLISAV-B has the potential to expand the U.S. market to over $800 million by 2027, with HEPLISAV-B well-positioned to achieve a majority market share.

Clinical Pipeline

Dynavax is advancing a pipeline of differentiated product candidates that leverage its CpG 1018® adjuvant, which has demonstrated its ability to enhance the immune response with a favorable tolerability profile in a wide range of clinical trials and real-world commercial use.

Shingles vaccine program:

Z-1018 is an investigational vaccine candidate being developed for the prevention of shingles in adults aged 50 and older.

In June, Dynavax presented results from a Phase 1 randomized, active-controlled, dose escalation, multicenter trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of Z-1018, at the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases' 2023 Annual Conference on Vaccinology Research. These results demonstrate the opportunity to develop a shingles vaccine with improved vaccine tolerability and comparable efficacy to Shingrix and support the continued development of Dynavax's shingles vaccine candidate.

In the second half of 2023, Dynavax plans to assess the regulatory pathway with the FDA to support the initiation of a Phase 1/2 trial in early 2024.

Tdap vaccine program:

Tdap-1018 is an investigational vaccine candidate intended for active booster immunization against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap).

Dynavax recently completed a pertussis challenge study in nonhuman primates demonstrating protection from disease upon challenge and robust Type 1 T helper (Th1) cell responses in nonhuman primates vaccinated with Tdap-1018.

The Company recently received Type B meeting feedback from the FDA on the Tdap-1018 clinical development plan and plans to submit an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) to the FDA in the fourth quarter of 2023 to support the initiation of a human challenge study.

Plague vaccine program:

DV2-PLG-01 is a plague (rF1V) vaccine candidate currently in a Phase 2 clinical trial in collaboration with, and fully funded by, the U.S. Department of Defense.

Earlier this year, the Company completed enrollment in Part 2 of the Phase 2 clinical trial, with top line data anticipated in 2024.

In July, Dynavax and the U.S. Department of Defense executed a contract modification to support advancement into a nonhuman primate challenge study, with the agreement now totaling $33.7 million through 2025.

CORPORATE UPDATES

Dynavax recently established a Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) comprised of renowned leaders in vaccine research and development. The SAB will work closely with Dynavax's leadership team on its efforts to develop innovative vaccines, as well support the evaluation of new development and technology opportunities. The SAB includes the following advisors:

Chair: Peter Paradiso, Ph.D., Principal of Paradiso Biologics Consulting LLC, former Vice President of New Business and Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Vaccines

Robert Coffman, Ph.D., Former Chief Scientific Officer of Dynavax, Adjunct Professor of Biomolecular Engineering, University of California Santa Cruz, and member of the National Academy of Sciences

Kathryn Edwards, M.D., Professor of Pediatrics Emerita, Former Director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and member of the National Academy of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences

Rino Rappuoli, Ph.D., Scientific Director of the Biotecnopolo di Siena Foundation, former Chief Scientist and Head, External R&D at GSK Vaccines, and member of the National Academy of Sciences

Dynavax has been recognized as a Great Place to Work in the U.S. by Great Place To Work®.

SECOND QUARTER 2023 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS

Total Revenues and Product Revenue, Net.

HEPLISAV-B vaccine product revenue, net was $56.4 million for the second quarter of 2023, compared to $32.7 million for the second quarter of 2022, representing year-over-year growth of 73%.

Other revenue was $3.8 million for the second quarter of 2023, compared to $1.1 million in the same period of 2022.

No CpG 1018 adjuvant product revenue was recorded in the second quarter of 2023, compared to $222.6 million in the second quarter of 2022, due to completion of all obligations and product delivery under the Company's CpG 1018 adjuvant COVID-19 collaboration agreements as of December 31, 2022.

Total revenues for the second quarter of 2023 were $60.2 million, compared to $256.5 million for the second quarter of 2022.

Cost of Sales - Product. Total cost of sales – product for the second quarter of 2023 decreased to $13.5 million, compared to $83.4 million in the second quarter of 2022. The decrease is due to no CpG 1018 adjuvant cost of sales – product for the second quarter of 2023 compared to $73.1 million in the second quarter of 2022. Cost of sales - product for HEPLISAV-B in the second quarter of 2023 increased to $13.5 million, compared to $10.3 million for the second quarter of 2022. The increase was due to higher sales volume driven by continued improvement in HEPLISAV-B market share and utilization.

Research and Development Expenses (R&D). R&D expenses for the second quarter of 2023 increased to $13.0 million, compared to $9.7 million for the second quarter of 2022. The increase was primarily driven by continued investments in our product candidates utilizing CpG 1018 adjuvant through preclinical and clinical collaborations and additional discovery efforts.

Selling, General, and Administrative Expenses (SG&A). SG&A expenses for the second quarter of 2023 increased to $37.1 million, compared to $36.2 million for the second quarter of 2022. The increase was primarily driven by higher compensation and related personnel costs and an overall increase in targeted commercial and marketing efforts to increase market share and maximize the ACIP's universal recommendation.

Net income. GAAP net income was $3.4 million, or $0.03 per share (basic and diluted) in the second quarter of 2023, compared to GAAP net income of $128.8 million, or $1.02 per share (basic) and $0.87 per share (diluted) in the second quarter of 2022.

Cash and Marketable Securities. Cash, cash equivalents and marketable securities were $681.5 million as of June 30, 2023.

2023 FINANCIAL GUIDANCE

Full year 2023 financial guidance has been revised to consist of the following expectations:

Raising HEPLISAV-B net product revenue between approximately $200 - $215 million, compared to the prior range of approximately $165 - $185 million

Reiterating research and development expenses between approximately $55 - $70 million

Reiterating selling, general and administrative expenses between approximately $135 - $155 million

Conference Call and Webcast Information

Dynavax will host a conference call and live audio webcast on Thursday, August 3, 2023, at 4:30 p.m. ET/1:30 p.m. PT. The live audio webcast may be accessed through the "Events & Presentations" page on the "Investors" section of the Company's website at . A replay of the webcast will be available for 30 days following the live event.

To dial into the call, participants will need to register for the call using the caller registration link. It is recommended that participants dial into the conference call or log into the webcast approximately 10 minutes prior to the call.

Important U.S. Product Information

HEPLISAV-B is indicated for the prevention of infection caused by all known subtypes of hepatitis B virus in adults aged 18 years and older.

For full U.S. Prescribing Information for HEPLISAV-B, click here.

Important U.S. Safety Information (ISI)

Do not administer HEPLISAV-B to individuals with a history of a severe allergic reaction (e.g., anaphylaxis) after a previous dose of any hepatitis B vaccine or to any component of HEPLISAV-B, including yeast.

Appropriate medical treatment and supervision must be available to manage possible anaphylactic reactions following administration of HEPLISAV-B.

Immunocompromised persons, including individuals receiving immunosuppressant therapy, may have a diminished immune response to HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis B has a long incubation period. HEPLISAV-B may not prevent hepatitis B infection in individuals who have an unrecognized hepatitis B infection at the time of vaccine administration.

The most common patient-reported adverse reactions reported within 7 days of vaccination were injection site pain (23% to 39%), fatigue (11% to 17%), and headache (8% to 17%).

About Dynavax

Dynavax is a commercial-stage biopharmaceutical company developing and commercializing innovative vaccines to help protect the world against infectious diseases. The Company has two commercial products, HEPLISAV-B® vaccine [Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant), Adjuvanted], which is approved in the U.S., the European Union and Great Britain for the prevention of infection caused by all known subtypes of hepatitis B virus in adults 18 years of age and older, and CpG 1018® adjuvant, currently used in multiple adjuvanted COVID-19 vaccines. Dynavax is advancing CpG 1018 adjuvant as a premier vaccine adjuvant with adjuvanted vaccine clinical programs for shingles and Tdap, and through global collaborations, currently focused on adjuvanted vaccines for COVID-19, plague, seasonal influenza and universal influenza. For more information about our marketed products and development pipeline, visit and follow Dynavax on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Forward-Looking Statements

This press release contains "forward-looking" statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, which are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties. All statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements can generally be identified by the use of words such as "anticipate," "believe," "continue," "could," "estimate," "expect," "forecast," "intend," "will," "may," "plan," "project," "potential," "seek," "should," "think," "will," "would" and similar expressions, or the negatives thereof, or they may use future dates. Forward-looking statements made in this document include statements regarding financial guidance, the development and potential approval of vaccines containing CpG 1018 adjuvant by us or by our collaborators, the timing of IND filings, the timing of initiation and completion of clinical studies and the publication of results. Actual results may differ materially from those set forth in this press release due to the risks and uncertainties inherent in our business, including, the risk that actual demand for our products may differ from our expectations, risks related to the timing of completion and results of current clinical studies, risks related to the development and pre-clinical and clinical testing of vaccines containing CpG 1018 adjuvant, whether use of CpG 1018 adjuvant will prove to be beneficial in these vaccines, as well as other risks detailed in the "Risk Factors" section of our Annual Report on Form 10-Q for the quarter ended June 30, 2023 and periodic filings made thereafter, as well as discussions of potential risks, uncertainties and other important factors in our other filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. These forward-looking statements are made as of the date hereof, are qualified in their entirety by this cautionary statement and we undertake no obligation to revise or update information herein to reflect events or circumstances in the future, even if new information becomes available. Information on Dynavax's website at is not incorporated by reference in our current periodic reports with the SEC.

For Investors/Media:

Paul Cox

[email protected]

510-665-0499

Nicole Arndt

[email protected]

510-665-7264

SOURCE Dynavax Technologies

VaccinePhase 1Phase 2Clinical ResultFinancial Statement

100 Deals associated with Adjuvanted plague vaccine(Dynavax Technologies Corporation/United States Department of Defense)

Login to view more data

R&D Status

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

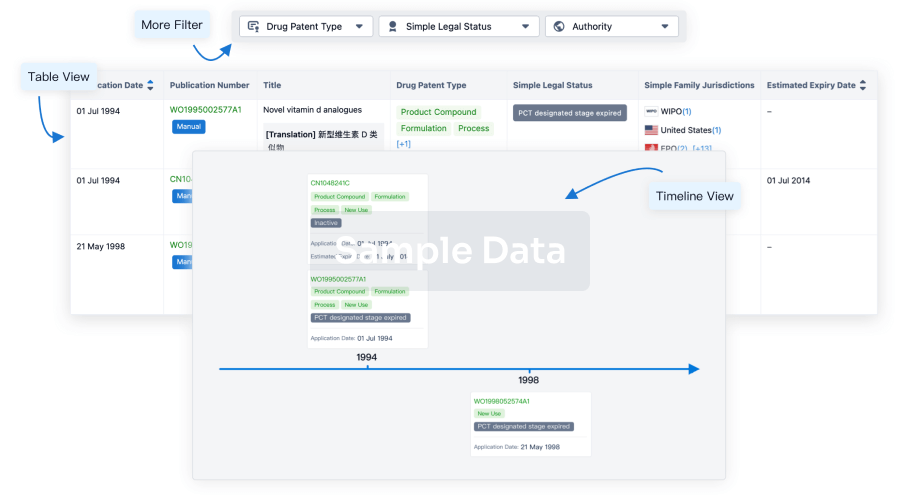

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

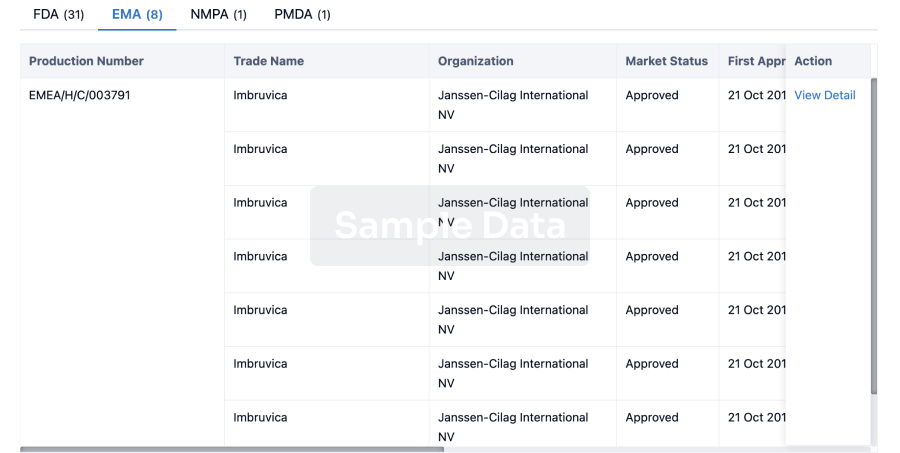

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

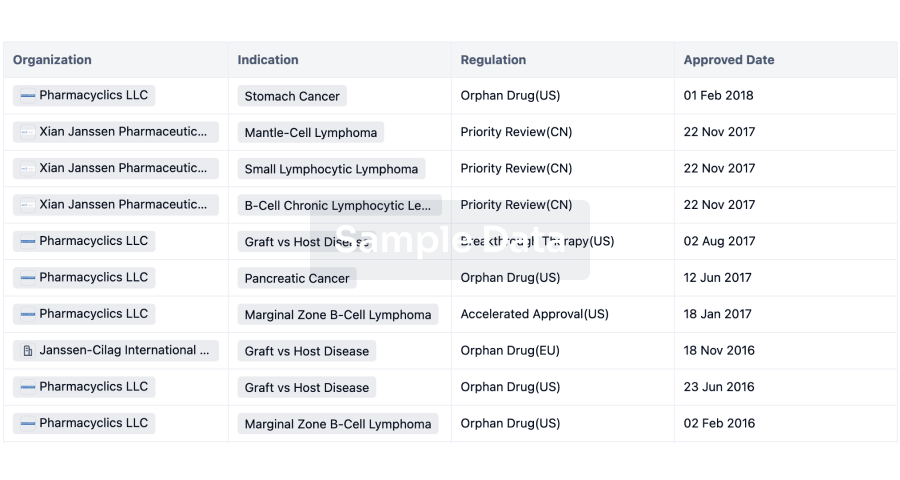

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free