Request Demo

Last update 14 Aug 2025

Biogenics Research Institute

Last update 14 Aug 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Biogenics Research Institute

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Biogenics Research Institute

Login to view more data

9

Literatures (Medical) associated with Biogenics Research Institute01 Aug 2019·Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & ImmunologyQ2 · MEDICINE

Frequency of goose and duck down causation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis within an 80-patient cohort

Q2 · MEDICINE

Article

Author: Jacobs, Robert L ; Jacobs, Matthew R ; Ramirez, Robert M ; Andrews, Charles P

BACKGROUND:

A variety of antigens have been identified as causative of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), which is characterized by inflammation to the lung parenchyma that is induced by exposure. Goose and duck down (GDD) bedding is often overlooked by physicians as a potential cause, yet the use of GDD has markedly increased in recent years, paralleling an increased frequency of reports of GDD-induced HP.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the frequency of GDD as the causative antigen in patients with HP who use bedding that contains GDD.

METHODS:

Patients referred with a working diagnosis of HP underwent a detailed environmental history. Those who were using GDD were asked to remove it as an avoidance procedure. Signs, symptoms, spirometry, and inflammatory markers were followed up at weekly intervals for up to 1 month to determine the effect of remediation.

RESULTS:

Eighty patients with HP were seen during an 8-year period. Thirty-two patients (40%) were using GDD bedding. Of these 32 patients, 12 (37.5% of those exposed and 15% of the total HP population experienced remission (or nonprogression) of disease by simply avoiding GDD bedding. Eleven (92%) of these 12 patients were female. In patients with GDD-induced HP, lung biopsy patterns were varied.

CONCLUSION:

Approximately one-third of patients with HP, who slept with GDD, had persistent improvement or remission with simple avoidance. The higher incidence of GDD-induced HP in females may be hormonal and/or sociocultural related. Lung biopsy findings were across the spectrum of histopathologic patterns. Avoidance-challenge techniques were effective in confirming diagnoses and causation and mitigating the need for additional remediation.

01 May 2016·The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice

Environmental challenge: An effective approach for diagnosis and remediation of exacerbations of hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Letter

Author: Jacobs, Robert L ; Jacobs, Matthew R

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is an inflammatory lung disorder caused by the inhalation of an organic antigen in predisposed patients. Activation of the immune system, directed toward the antigen, leads to recruitment of inflammatory cells resulting in insult to respiratory dynamics. There are 3 temporal patterns of HP based on the history of symptoms and the course of the disease: acute, subacute, and chronic. Exacerbations may occur in all 3 forms depending on levels of exposure. Many cases can quickly be diagnosed using somewhat antiquated criteria. Effective remediation, or avoidance, can be undertaken and a favorable outcome obtained. Many patients, however, fail to meet enough criteria to establish a clear diagnosis, leading to misdiagnosis or a significant delay in diagnosis. Likewise, with a biopsy consistent with HP, failure to identify a possible causative antigen and environment is very common. Both the above situations may lead to failure to prevent progression of the disorder, causing increased morbidity and mortality. Here, we present a case, only meeting partial criteria, demonstrating the effectiveness of an environmental avoidance challenge procedure in establishing the diagnosis and in the confirmation of adequate remediation. A nonsmoking woman, age 75 years, with no history of respiratory tract symptoms was referred after developing a month-long, labored cough and a profound sense of fatigue. She had no wheezing, fevers, night sweats, hemoptysis, or weight loss. Spirometry revealed a reduced forced vital capacity. Computed tomography of the chest showed bilateral apical and upper-lobe infiltrates. A sedimentation rate of 99 mm/h (0-20 mm/h) and a Creactive protein level of 137 mg/L (0.0-3.30 mg/L) were recorded. Serum precipitins were negative to a panel of Aspergillus antigens including Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, and A fumigatus 1 and 6. A second panel was also negative including pigeon serum, A fumigatus 1 and 6, Thymus vulgaris, Faenia retivirgula, Thermoactinomyces candidus, Aureobasidium pullulans, Saccharomonospora viridis, and Thermoactinomyces sacchari. HP was the tentative diagnosis, and she was advised to move from her home while an environmental investigation was conducted. The patient lived in a 25-year-old home that was located on a farm; however, she did not participate in any farming activities. The central forced-air handling system had developed a condensate line blockage 7 to 8 years previously; however, no dust, nor discoloration, was observed on the air conditioning registers. There had been a roof leak located over the living room area nearly 6 months before the patient’s onset of respiratory symptoms. The roof was replaced; however, no mold contamination was discovered. She slept on a goose/duck down pillow. A “musty” smell, indicative of volatile organic compounds probably produced by molds, was noted throughout the residence by the patient and others; however, no mold growth was visualized. While the patient was avoiding the home, 2 investigational companies inspected the home, yet neither was able to identify a possible causative factor. Minimal generic remediation suggestions were made and executed, including removal of goose/duck down from the home. Eleven days after moving from the home, she had only a very mild cough and her energy levels had returned to normal. The lungs were clear; however, the forced vital capacity was slightly abnormal. The sedimentation rate and the C-reactive protein level had returned to normal. She was advised to return to her home to undergo an environmental challenge to determine whether remediation had been effective. She continued to do well with normal energy levels, throat clearing, and a slight cough until reactivation of a labored cough and profound tiredness and fatigue approximately 4 weeks after returning to the home. Rather than, again, moving her from the home, prednisone, 20 mg twice daily, was begun. Further investigation by a family member revealed mold growth around a wall light fixture beneath the area of the roof leak. Upon opening the wall space, heavy mold growth was discovered, but not identified. Remediation was undertaken and completed. Prednisone was tapered, and she was followed for 3 months to ascertain nonprogression (Figure 1). This case is representative of many patients seen by physicians in which there are minimal criteria for establishing a working diagnosis. Formal pulmonary function testing and bronchoscopy with biopsy were not done. Serum precipitins were negative. Two investigations by industrial hygienists of the home failed to reveal a possible causative antigen, and a generic remediation attempt failed to remove the causative antigen. The environmental challenge back into the home required 27 days of exposure before an exacerbation occurred. All these factors are inconsistent with the current perception of parameters to diagnose and treat HP. An effective solution to a complex problem revolves around an avoidance challenge procedure. Moving to a new residence was a successful intervention. After investigations and modest remediation, in which no causative factors were found, the patient returned to the home. Exacerbation of symptoms and inflammatory markers after 27 days of exposure confirmed the home as the causative environment. The most recently published diagnostic criteria state that exacerbations should occur within several hours after exposure to the causative environment; however, reports have shown that days to weeks may pass before signs and symptoms recur. Increased inflammatory markers may precede symptoms, changes in spirometry, and radiographic

01 Aug 2015·Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & ImmunologyQ2 · MEDICINE

Efficacy and safety of beclomethasone dipropionate nasal aerosol in children with perennial allergic rhinitis

Q2 · MEDICINE

Article

Author: Jacobs, Robert L ; Berger, William E ; Small, Calvin J ; Tantry, Sudeesh K ; Amar, Niran J ; Li, Jiang

BACKGROUND:

Beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) nasal aerosol (non-aqueous) is approved for management of seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR) in adolescents and adults.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of BDP nasal aerosol at 80 μg/day in children with PAR.

METHODS:

This 12-week, phase 3, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study randomized 547 children (4-11 years old) with PAR to once-daily BDP nasal aerosol at 80 μg/day or placebo. The primary end point was change from baseline in average morning and evening reflective total nasal symptom score (rTNSS) during the first 6 weeks of treatment in patients 6 to 11 years old. Changes from baseline in average morning and evening instantaneous TNSS (iTNSS) in children 6 to 11 years old and average rTNSS and iTNSS in children 4 to 11 years old were assessed during the first 6 weeks of treatment.

RESULTS:

Improvements were significantly greater with BDP nasal aerosol than with placebo during the first 6 weeks of treatment in children 6 to 11 years old in average morning and evening rTNSS and iTNSS (mean treatment difference -0.66 [P = .002] and -0.58 [P = .004], respectively). Improvements in average morning and evening rTNSS and iTNSS also were significantly greater in patients 4 to 11 years receiving BDP nasal aerosol than with placebo during the first 6 weeks of treatment (P = .002 and P = .004, respectively). Similar improvements were seen during 12 weeks of treatment. The safety profile of BDP nasal aerosol was comparable to that of placebo.

CONCLUSION:

The BDP nasal aerosol at 80 μg/day in children 4 to 11 years old was well tolerated and effective in controlling nasal symptoms of PAR.

TRIAL REGISTRATION:

www.clinicaltrials.gov, identifier NCT01783548.

100 Deals associated with Biogenics Research Institute

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Biogenics Research Institute

Login to view more data

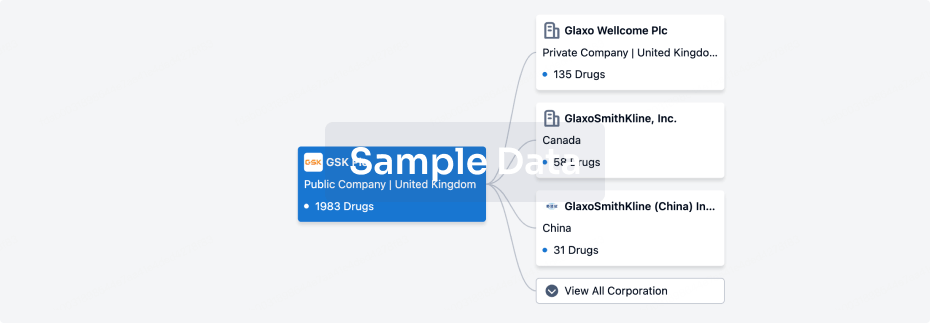

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 11 Sep 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

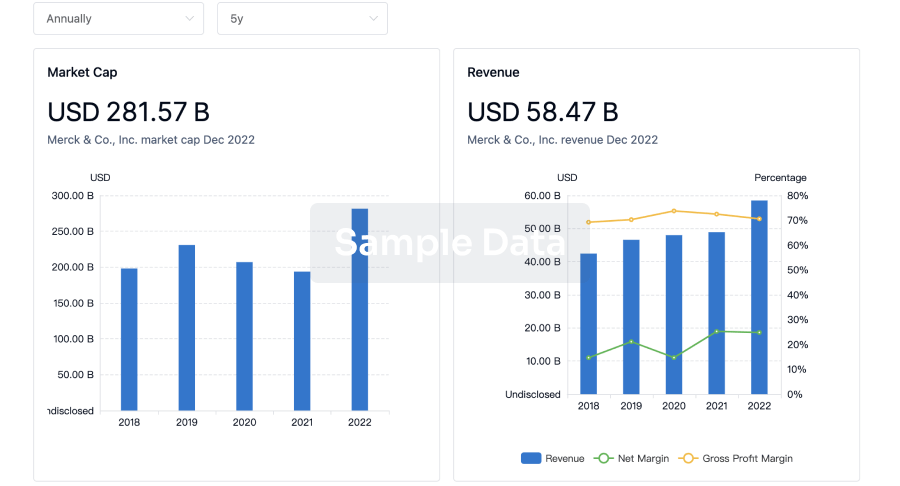

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

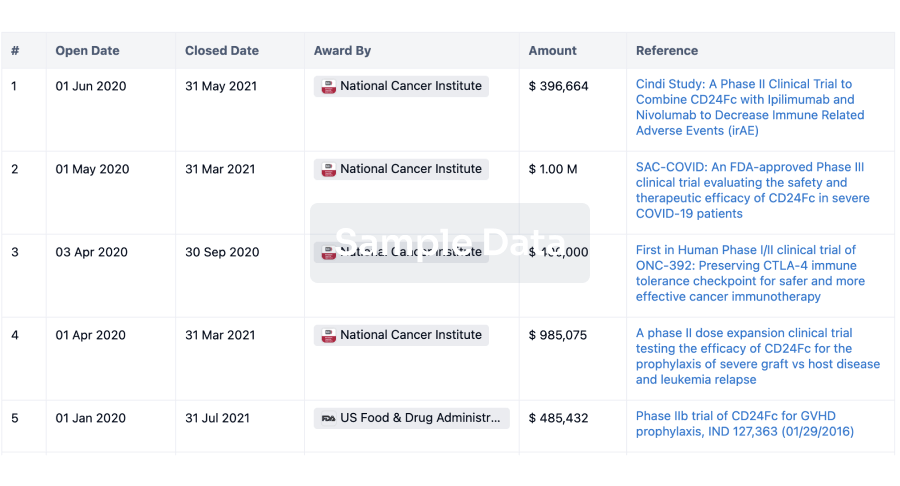

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

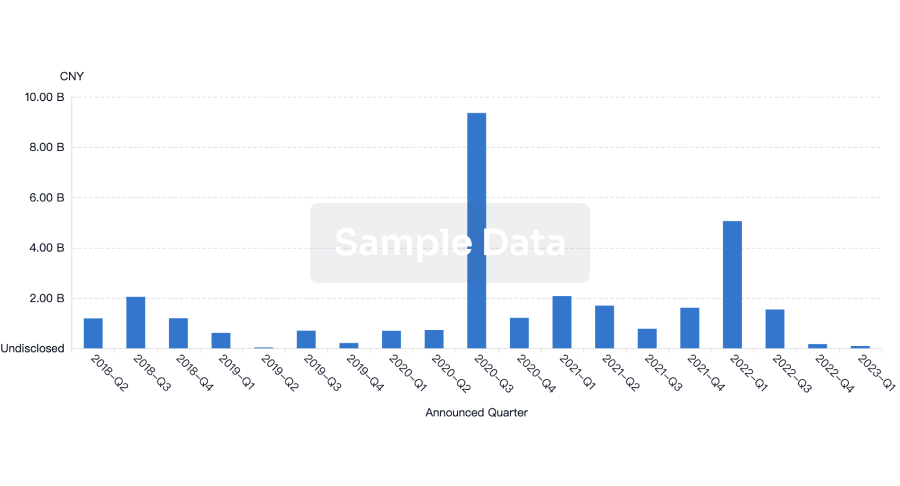

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free