Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Nvelop Therapeutics, Inc.

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Nvelop Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Nvelop Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

17

News (Medical) associated with Nvelop Therapeutics, Inc.04 Mar 2025

European venture capital firm Sofinnova Partners has raised 1.2 billion euros, or nearly $1.3 billion, in fresh funds to invest in life sciences and healthcare companies, the group announced Tuesday.With the new funds, we anticipate supporting 50 to 60 new companies, empowering a new wave of entrepreneurs tackling some of the worlds most pressing health and sustainability challenges, Antoine Papiernik, Sofinnovas chairman, said in a statement.Sofinnova is one of the most active biotech investors, according to data from BioPharma Dive. Since 2022, it has backed 21 biotech companies, spanning many drugmaking modalities and disease areas. Among its investments are gene therapy company Chroma Medicine, which announced late last year it would merge with Nvelop Therapeutics to form nChroma Bio, as well as CinCor Pharma and Amolyt Pharma, which were acquired by AstraZeneca in 2023 and 2024 respectively.The 1.2 billion haul means the firm, which was launched in 1972, has more than 4 billion in assets under management. Sofinnova didnt specify how those funds will be allocated across its investment strategies, which include backing drug startups as well as companies developing medical devices and digital therapeutics. Further details on individual funds will be revealed upon their final closings, the firm said.The raise is one of the first for a major life sciences venture firm in 2025. Last year, notable startup backers including Arch Venture Partners, Forbion and Flagship Pioneering announced fresh funds each exceeding $2 billion, despite what industry observers described as a sluggish fundraising environment.The number of biotech funds raised by venture capital firms peaked in 2021 with 137 new funds bringing in $30.8 billion, according PitchBook the height of a frenzy in investment and initial public offerings for healthcare and life sciences companies. In 2024, that number dropped to 38, though the amount raised,at $16 billion,didnt drop as sharply.More capital is flowing into fewer, but larger deals as investors prioritize “companies that demonstrate validated clinical data and clear commercialization pathways,“ Pitchbook report author Kazi Helal wrote.Conversely, seed and early-stage investments are likely to face significant challenges, as the scarcity of new fund closures among emerging managers and weak exit activity will constrain capital recycling, he wrote. '

Acquisition

12 Jan 2025

Genetic medicine startup Tune Therapeutics has raised another $175 million to develop therapies capable of tuning genes to treat disease, rather than editing them by cutting or replacing DNA directly.Tune disclosed the Series B round on Sunday, the eve of the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference, which regularly features as a curtain-raising meeting for the biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors. It follows a busy week for private financing in biotech, adding to nearly $2 billion worth of investment announced by venture firms tracked by BioPharma Dive since Monday.Tunes lead therapy, dubbed Tune-401, is designed to treat chronic hepatitis B by silencing the viral DNA thats both integrated into an infected cells genome and circulating in loops within the cell. More than 250 million people worldwide are estimated to have chronic hepatitis B infections, which can cause liver failure and cancer. Researchers see altering gene expression via epigenetic editing as a way to block cells from producing more of the virus, rather than fighting the virus directly, as existing drugs do.Its thinking about addressing a leak by trying to shut off the faucet, said Akira Matsuno, one of Tunes co-founders and now its chief financial officer. Many therapies ... either try to slow down the pace or are really good at getting the water out of the tub, if you will. But ultimately, you have to be able to shut off the faucet.The company has begun a Phase 1 trial of Tune-401 in New Zealand and Hong Kong.Scientists have described epigenetic editing as more efficient and less disruptive than DNA-cutting technologies like CRISPR, proposing that it could also be used to turn genes on or off.We have these targeted, really specific therapies that do not confer DNA damage, Matsuno said. It opens up a lens with regards to the types of opportunities and settings we can go into over time.Tunes science builds on research by genetic medicine pioneers Charles Gersbach at Duke University and Fyodor Urnov at the University of California, Berkeley.The companys Series B round was co-led by New Enterprise Associates, Yosemite, Regeneron Ventures and Hevolution Foundation. When Tune launched in 2021, it raised a $40 million Series A.Chronic diseases of aging are accelerating in incidence, prevalence, and severity, and current approaches are simply inadequate, William Greene, chief investment officer at Hevolution Foundation, said in a statement. It is our belief that epigenetic editing may prove to be the transformative modality we need to enable a new era of regenerative medicine.Tune is one of several companies working to advance epigenetic editing as a drugmaking technology. Among its competitors in the field is nChroma Bio, which formed late last year from a merger between Chroma Bio and Nvelop Therapeutics. NChroma is also researching a potential treatment for hepatitis B, but has not entered human testing. Epicrispr Therapeutics, formerly known as Epic Bio, is researching treatments for several conditions including a form of muscular dystrophy and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.Beyond epigenetic editing specifically, startups working in genetic medicine are seeing less investment flow into their field. Funding of cell and gene therapy developers declined in 2024 compared to the two years prior, according to BioPharma Dive data. '

Phase 1Gene TherapysiRNA

02 Jan 2025

2024 was the year of the private megaround.

Nine-figure financings dominated biotech’s venture funding landscape, with 96 such rounds tallied by

Endpoints News

. The bevy of megarounds drowned out smaller investments and perhaps diverted some capital away from earlier-stage, nascent ideas that in the heydays of 2020 and 2021 would’ve gotten more attention from investors.

“Everything takes more money to do. That’s a part of it,” said Srinivas Akkaraju, founder of Samsara BioCapital, which invested in multiple megarounds in 2024, including Ottimo Pharma’s $140 million Series A on Dec. 19.

The breakneck pace of megarounds beat the prior two years and comes close to the tally of 106 recorded by Silicon Valley Bank in 2021. It also shows investors are concentrating their bets on proven management teams and drug candidates that are already being tested in humans. (That said, preclinical companies still attracted nearly one-third of the splashy financings).

Jonathan Norris, a managing director in the healthcare banking division of HSBC, told Endpoints he counted 106 megarounds in 2024. In an email, he highlighted that the median post-money valuation has significantly increased for crossover deals. In 2021, the median was $280 million. In 2024, it was $370 million.

With IPOs still largely out of the question, startups need more fuel to last through the so-called winter on the public markets.

“If we give a little bit more, what is the impact on your budget and runway? Can we, for example, tranche it in a way that is still acceptable from a risk perspective, but it doesn’t necessarily require a public market to get to that key value inflection point?” asked Wouter Joustra, general partner at Forbion.

The Dutch biotech investor took part in 10 megarounds in 2024, and the firm leads about 90% of the deals in which it’s involved, Joustra said.

The large financings can also attract better management teams and higher-quality employees down the line, according to both Joustra and Akkaraju.

“Some C-suite members that otherwise would have been in a public company are now more comfortable to go to a private company with a megaround, because they see that refinancing risk is significantly lower than it might have been otherwise,” Joustra said.

Investors are also injecting more capital so that startups have fewer fundraising headaches — and distractions to clinical development — in the years to come.

“In many cases, what I find is, management teams will actually raise the money that they know they need, but they would prefer to have 10% to 20% more,” Akkaraju said. That’s “either for cushion, or the classic is, ‘We’re generating this data, but we didn’t put into the budget all the extra shit we got to do that if the data is positive, we can start the next trial immediately or very quickly instead of a one-year gap.’”

It’s too early to tell what kind of impact, if any, President-elect Donald Trump’s various healthcare appointees could have on the industry. It might lead investors to further concentrate their bets, according to Akkaraju, and that means megarounds could remain popular.

“Whereas we were going into … a nice, slow ramp-up to a better and more and more constructive mentality about investing into companies, I think we’ve taken at least a half-step back, if not a full step back,” Akkaraju said. “We’ll see how things hopefully stabilize over the course of the first couple of quarters next year.”

Ninety-six is a decent sample size, so we took a look at the profiles of the companies that recorded megarounds. Most were US-based, with about a dozen in Europe and two in China. (There is a chance we missed some megarounds. Not all are disclosed on time, and there could have been language barriers.)

Of the 94 companies, 14 have a female CEO. Five companies appeared to have no CEO. Only two have already been acquired or merged. In April, Genmab

scooped up

ADC maker ProfoundBio, and in December, Nvelop

merged

with Chroma less than a year after coming out of stealth. Three went public:

Alumis

,

BioAge

and

Zenas

.

About one-third (33 companies) are fully, or have a foot, in oncology. Only three companies are known to be working in obesity. With so much investor and large pharma interest in obesity drugs, one would think that stat would be higher.

AcquisitionIPO

100 Deals associated with Nvelop Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Nvelop Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

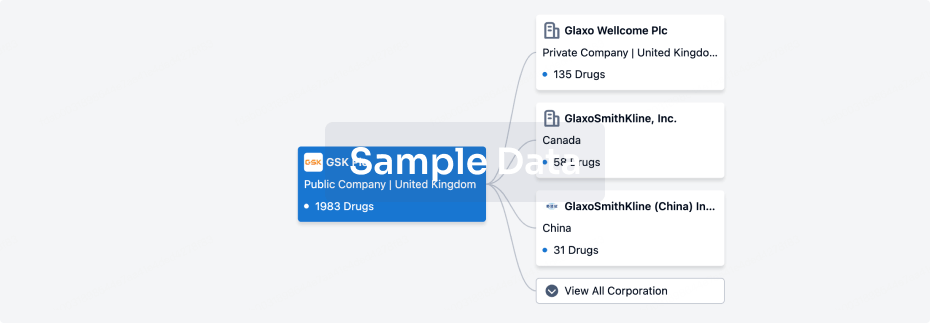

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 19 Sep 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

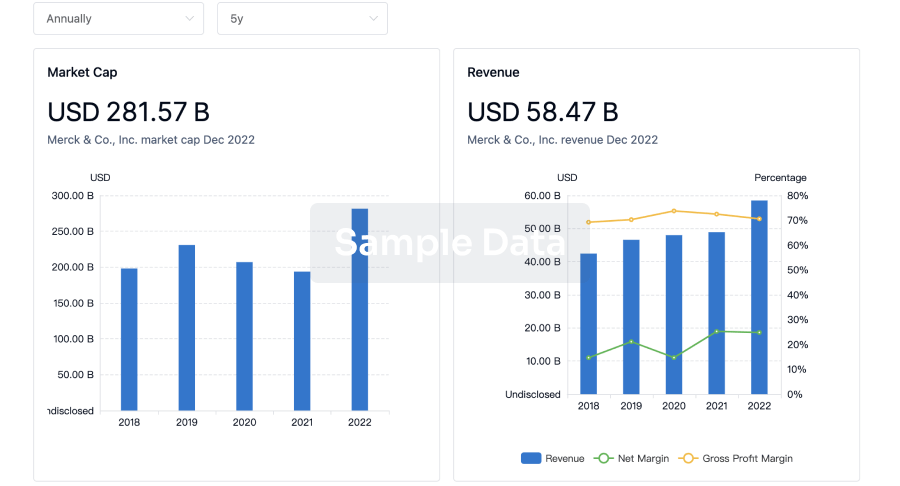

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

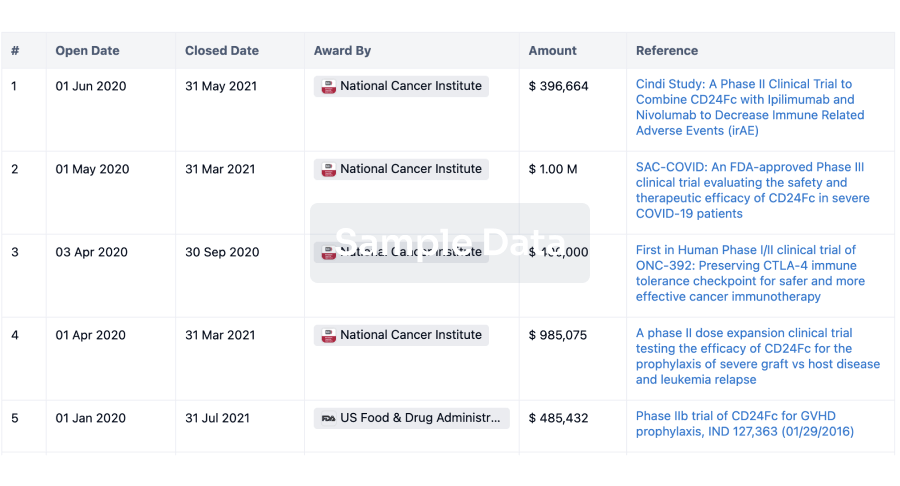

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

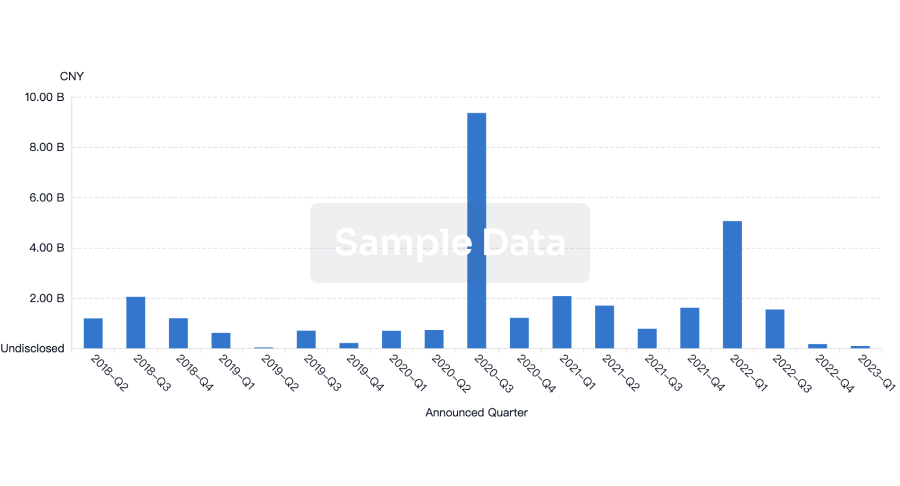

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free