Request Demo

Last update 07 Nov 2025

Third Rock Ventures LLC

Last update 07 Nov 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Third Rock Ventures LLC

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Third Rock Ventures LLC

Login to view more data

3

Literatures (Medical) associated with Third Rock Ventures LLC08 Nov 2018·Nature

Immune-cell crosstalk in multiple sclerosis

Communications

Author: Ransohoff, Richard M.

Interactions between the B and T cells of the human immune system are implicated in the brain disease multiple sclerosis.It emerges that B cells make a protein that is also made in the brain, and that T cells recognize this protein.

22 Apr 2015·Science translational medicineQ1 · MEDICINE

An implantable microdevice to perform high-throughput in vivo drug sensitivity testing in tumors

Q1 · MEDICINE

Article

Author: Baselga, Jose ; Landry, Heather M. ; Fuller, Jason E. ; Tepper, Robert I. ; Santini, John T. ; Cima, Michael J. ; Jonas, Oliver ; Langer, Robert

An implantable microdevice is demonstrated to release microdoses of multiple drugs into confined regions of tumors and allows for assessment of each drug’s efficacy to identify optimal therapy.

eLife

A microglia clonal inflammatory disorder in Alzheimer’s disease

Article

Author: Hayashi, Samantha Y ; Ay, Oyku ; Kappagantula, Rajya ; Chesworth, Richard ; Abdel-Wahab, Omar ; Casanova, Jean-Laurent ; Craddock, Barbara ; Weber, Leslie ; Zhou, Ting ; Socci, Nicholas D ; Lazarov, Tomi ; Geissmann, Frédéric ; Ransohoff, Richard M ; Hu, Yang ; Viale, Agnes ; Vicario, Rocio ; Baako, Ann ; Iacobuzio-Donahue, Christine A ; Miller, W Todd ; Alberdi, Araitz ; Elemento, Olivier ; Ogishi, Masato ; Lopez-Rodrigo, Estibaliz ; Boisson, Bertrand ; Fragkogianni, Stamatina

Somatic genetic heterogeneity resulting from post-zygotic DNA mutations is widespread in human tissues and can cause diseases, however, few studies have investigated its role in neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here, we report the selective enrichment of microglia clones carrying pathogenic variants, that are not present in neuronal, glia/stromal cells, or blood, from patients with AD in comparison to age-matched controls. Notably, microglia-specific AD-associated variants preferentially target the MAPK pathway, including recurrent CBL ring-domain mutations. These variants activate ERK and drive a microglia transcriptional program characterized by a strong neuro-inflammatory response, both in vitro and in patients. Although the natural history of AD-associated microglial clones is difficult to establish in humans, microglial expression of a MAPK pathway activating variant was previously shown to cause neurodegeneration in mice, suggesting that AD-associated neuroinflammatory microglial clones may contribute to the neurodegenerative process in patients.

344

News (Medical) associated with Third Rock Ventures LLC05 Nov 2025

Today, a brief rundown of news from Soleno Therapeutics and Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, as well as updates from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim and Azalea Therapeutics that you may have missed.Shares of Soleno Therapeutics fell by nearly 30% Wednesday despite quarterly earnings results that were in line with Wall Streets expectations. Soleno said Tuesday that sales of its Prader-Willi syndrome drug Vykat XT reached $66 million between July and September and that, after only two quarters of selling the treatment, its turning a profit. However, executives on a conference call revealed a slowdown in patient start forms and an uptick in treatment discontinuations in August and September. In a note to clients, Stifel analyst James Condulis noted that the companys messaging is stoking questions about the drugs growth trajectory and safety, the latter of which was the subject of an August report from short-selling activist firm Scorpion Capital. Ben FidlerSales of Madrigal Pharmaceuticals Rezdiffra, the first marketed medicine for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, again topped analysts estimates. Third-quarter results disclosed Tuesday showed Rezdiffra pulled in net sales of over $287 million, $40 million higher than consensus projections. The number of patients on treatment also jumped from about 23,000 at the end of the second quarter to 29,500 as of Sept. 30, indicating accelerating patient/prescriber demand, wrote Leerink Partners analyst Thomas Smith. The numbers reflect a market for MASH drugs thats expanding much more rapidly than we anticipated, added Cantor Fitzgeralds Prakhar Agrawal. Madrigal shares have climbed more than 40% this year. Ben FidlerAmgen has stopped a trial testing a regimen involving its experimental antibody bemarituzumab in gastric cancer, marking the latest setback for a drug acquired in a $1.9 billion buyout four years ago. Amgen disclosed the studys cessation in a third-quarter earnings release, but didnt provide additional details. An earlier Phase 3 trial evaluating bemarituzumab with chemotherapy showed that the drug meaningfully extended survival compared to chemotherapy alone at a primary analysis, but that benefit shrank to a difference that was no longer statistically significant after further follow-up. Jonathan GardnerBoehringer Ingelheim is paying $48 million up front and in the near term to Switzerland-based CDR-Life for rights to an experimental tri-specific antibody drug thats being developed for B-cell driven autoimmune disorders. The drug, called CDR111, is intended to reset the immune systems of people with disorders such as lupus, multiple sclerosis or certain types of arthritis by depleting levels of malfunctioning B cells.The deal builds on an existing collaboration between Boehringer and CDR-Life on an eye disease drug, and offers the biotech an additional $522 million, as well as potential sales royalties, should the program progress. Jonathan Gardner Azalea Therapeutics, a startup co-founded by Nobel Prize winner Jennifer Doudna,launched Tuesday with $82 million to develop a type of in vivo cell therapy technology.The financing included a recently closed $65 million Series A financing led by Third Rock Ventures and involvingRA Capital Management, Yosemite and Sozo Ventures, among others. Itll help Azalea advance preclinical programs targeting B-cell driven autoimmune conditions and malignancies, a multiple myeloma prospect, and a treatment for an undisclosed solid tumor. The startup will present some of its early research at a medical meeting later this month. Delilah Alvarado '

Phase 3ImmunotherapyCell TherapyFinancial Statement

04 Nov 2025

Figuring out how to transport genetic medicines to the right parts of the body remains one of the great technical challenges constraining CRISPR’s potential. Now, one of the inventors of a gene editing tool has launched a startup with a new solution.

Azalea Therapeutics, co-founded by Nobel laureate and CRISPR co-inventor Jennifer Doudna, has raised $82 million to develop therapies based on its so-called Enveloped Delivery Vehicles, or EDVs, it said Tuesday. Its approach aims to merge the perks and overcome the limitations of the two most widely-studied delivery vessels: lipid nanoparticles and viral vectors.

“They really have the best of both worlds,” Azalea co-founder, president and CEO Jenny Hamilton told

Endpoints News

in an interview.

Although Azalea envisions many potential applications of EDVs, the startup is focusing its initial efforts on developing infused drugs that reprogram immune cells to create

in vivo

CAR-T cell therapies for blood cancers. The approach could be a game-changer in bringing more affordable, convenient cell therapy cures to the masses. But Azalea is far from alone in its endeavor.

Four pharma companies have acquired startups working on

in vivo

CAR-T therapies this year, and dozens of companies are joining the fray. Despite the competition, Azalea’s founders and investors believe that the

in vivo

CAR-T market will be big enough for another well-funded startup.

“There’s not going to be one party that wins,” Third Rock Ventures partner Andrea van Elsas told Endpoints. “Azalea has cracked the nut in a way that’s unique, and I believe has the potential to be not only safe and efficacious, but also durable.”

Third Rock led the Berkeley, CA-based startup’s $17 million seed round and recently closed $65 million Series A. RA Capital Management, Yosemite, Sozo Ventures and undisclosed individual investors also chipped in.

Azalea’s approach fits into the broader umbrella of delivery tools that are sometimes called virus-like particles, or VLPs. It’s a loose term applied to technologies that resemble viruses in appearance, but are unable to replicate and cause disease. Azalea’s particles are little spheres that bud off a cell’s plasma membrane and “very closely mimic an enveloped virus,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton began working on the approach as a postdoc in Doudna’s lab in 2018. The research led Hamilton and Doudna to co-found Azalea in 2023, and they published preclinical work describing their particular twist on the particles, the EDVs, in

Nature Biotechnology

the following year.

EDV surfaces are studded with viral proteins that help the particles bud from and fuse with cells. Antibody fragments jutting from the membrane help the particle target T cells. And the Cas9 ribonucleoprotein — the CRISPR scissors — is fused to the end of a lentiviral protein called Gag to package it inside the particle.

By swapping out different proteins on the surface of EDVs, Hamilton hopes it will be relatively simple to get the particles to target other cells in future uses of the technology, including targeting hematopoietic cells to treat blood diseases.

Hamilton said the production of EDVs is similar to the manufacturing process for lentiviral vectors — the viruses used to engineer commercial CAR-T cell therapies outside of the body. The company is working with a contract manufacturer to get clinical-grade vectors made in the next 12 months.

The treatment will be a one-time infusion without the need for chemotherapy. Azalea’s lead program is a CD19-targeted treatment for blood cancer and potential expansion in autoimmune disease. Hamilton said the new funding gives the company 18 months of runway “right to or right through” treating the first few patients — putting the potential first dosing in the spring of 2027.

Azalea is trailing behind other

in vivo

CAR-T companies,

but it’s betting that making the best possible version of the therapy requires attention to detail in how exactly the cancer-targeting chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, is integrated into cells.

Some companies use lentiviral vectors, which plop the gene into somewhat random spots, which may cause cancer. Others use RNA delivered via lipid nanoparticles, an impermanent approach that may provide a safety benefit but also makes a durable treatment more challenging. Some startups are using gene editing to insert the CAR genes permanently into so-called “safe harbors” of the genome, but the Azalea team thinks even that approach stops short of the ideal treatment.

UCSF gene editing scientist Justin Eyquem, who is also a co-founder of Azalea,

developed a potential workaround

to those problems by precisely placing the CAR genes into a specific part of the genome — the T cell receptor α constant (TRAC) locus — that normally controls how the cells recognize pathogens.

Rather than constantly cranking up the production of CARs, like some other approaches do — which can literally exhaust T cells and cause the therapy to lose effectiveness — the Azalea team believes that putting the gene under the immune system’s normal control could provide more durable responses.

“Once they see the antigen, they’ll expand,” van Elsas said. “But then, after the antigen is gone, cells contract again. It looks like an almost natural immune response. And I hadn’t seen anything like that before.”

The catch is that Azalea’s approach requires more than one delivery vessel. Azalea will use its EDV to deliver the CRISPR scissors to snip the TRAC locus, which creates an opening to insert the new CAR gene. But the company still needs a viral vector to deliver that gene. It is using a T cell targeting AAV developed by Eyquem’s lab.

Hamilton admits the method sounds complicated, but she said it works more smoothly than expected in mice, and that the approach may require a “surprisingly low” amount of drug.

Azalea is presenting the results of its mouse study at a gene editing conference later this month. According to the company’s abstract, a single dose of Azalea’s treatment reprogrammed about half of the T cells in the spleen into CAR-T cells, which fully eliminated the B cells responsible for blood cancer.

AcquisitionGene TherapyCell TherapyImmunotherapy

04 Nov 2025

CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna has revealed the latest modality she's applying the gene-editing technology to — in vivo CAR-T cell therapies. She helped found Azalea Therapeutics, which emerged from stealth on Tuesday with $82 million in funding to advance technology capable of engineering cells within patients. The startup's capital includes a $65-million series A led by Third Rock Ventures; RA Capital Management, Yosemite and Sozo Ventures also participated in the round. Azalea, born out of a research collaboration between Doudna's lab at the Innovative Genomics Institute and Justin Eyquem’s lab at the University of California San Francisco's Institute for Genomic Immunology, is developing a programmable genome editing platform dubbed Enveloped Delivery Vehicle (EDV). The technology is designed to deliver a CRISPR-Cas9 cargo, including a promoterless homology-directed repair template, to target T cells, enabling site-specific large genome insertion that may have improved durability, efficacy and safety compared with other gene editing methods. "By combining cell-selective delivery with site-specific genome integration, we can create potent and durable in vivo CAR-T and other cell-based therapies inside the body and extend the reach of genome engineering to many more patients," said Azalea co-founder, president and chief executive Jenny Hamilton, who previously was a post-doctoral fellow in Doudna's lab. According to Azalea, its EDV technology and a T cell-restricted promoter are capable of inserting CAR genes in vivo. While current CAR-T therapies can be curative for some cancer patients, their ex vivo, autologous manufacturing process are time-consuming and expensive — prompting a wave of pharmas to turn to in vivo technologies, especially as the modality holds promise in treating patients with autoimmune diseases (see – Spotlight On: Pharma buys into in vivo cell therapies).Novartis was one of the first entrants into the space, partnering with Vyriad last year to develop in vivo cell therapies. Since then, as Bristol Myers Squibb, AbbVie, and AstraZeneca have executed their own M&A plays to gain an in vivo foothold, buying Orbital Therapeutics, Capstan Therapeutics and EsoBiotec, respectively. Azalea's funding will help it move a CD19-based in vivo CAR-T therapy for B cell malignancies and autoimmune diseases into the clinic, and advance a BCMA-targeting programme for multiple myeloma. The company is also developing an undisclosed in vivo candidate for solid tumours.The biotech will provide a more detailed look at its EVD technology at the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy (ASGCT) meeting later this month.

ImmunotherapyCell TherapyGene TherapyASH

100 Deals associated with Third Rock Ventures LLC

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Third Rock Ventures LLC

Login to view more data

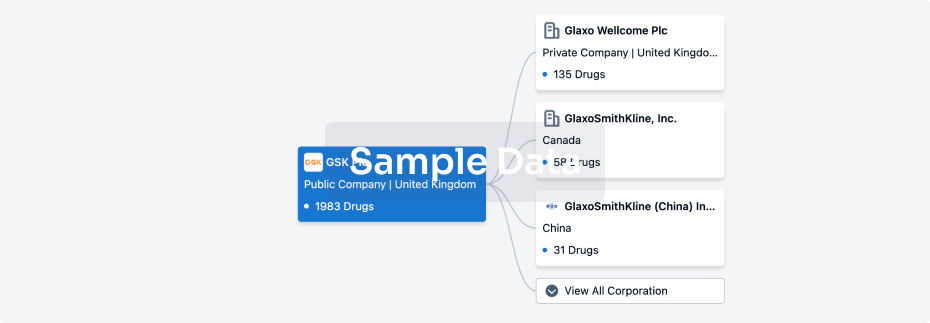

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 18 Dec 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

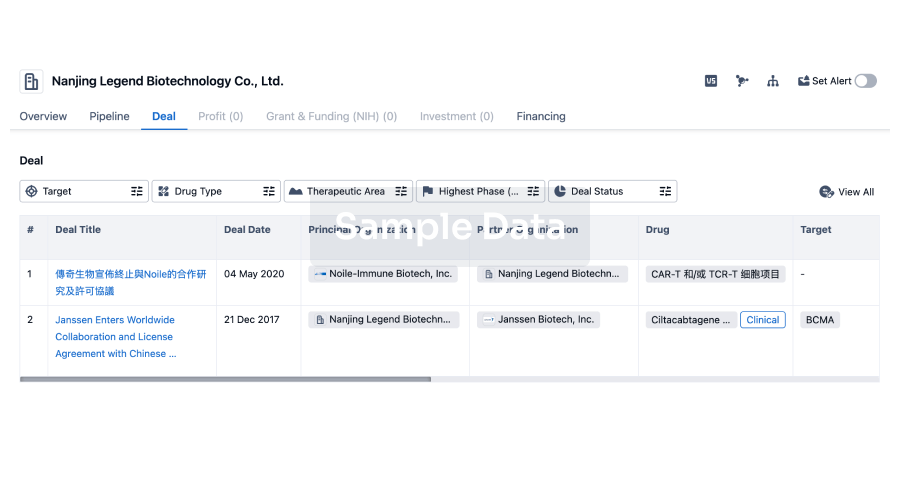

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

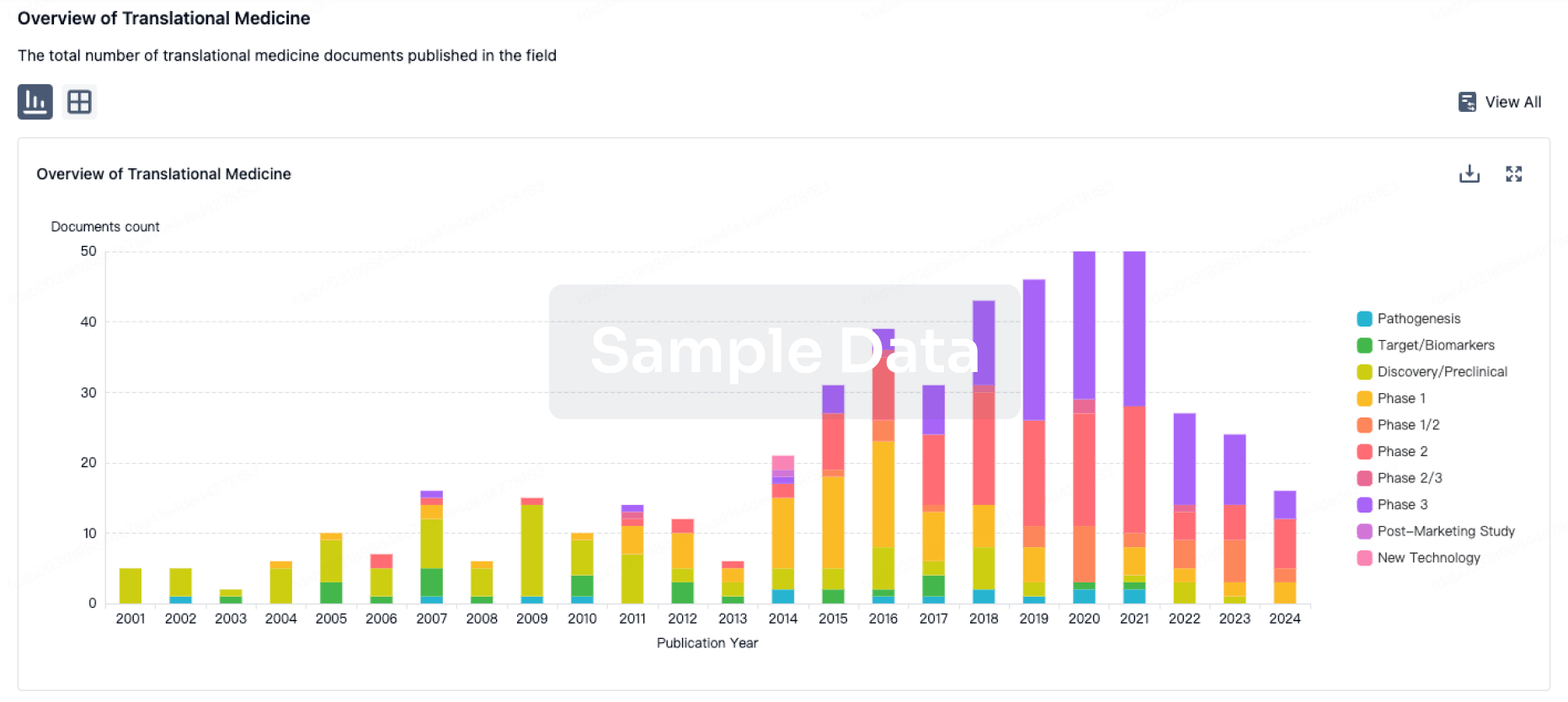

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

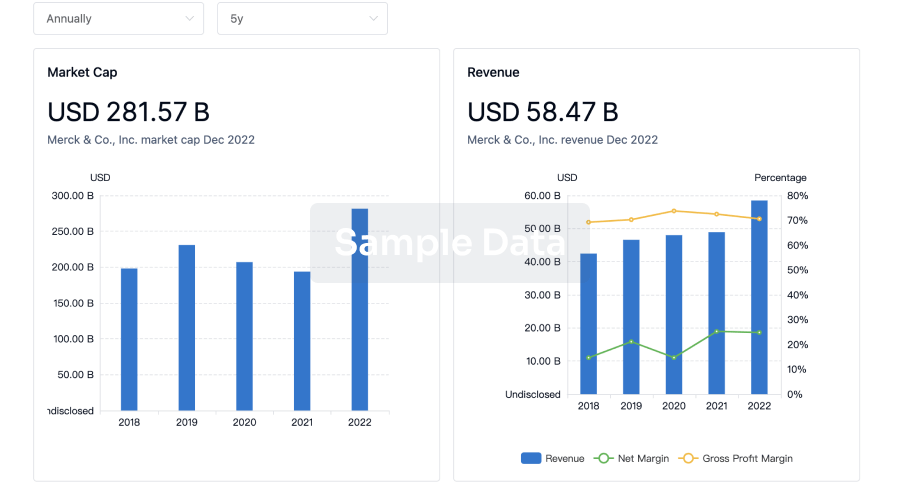

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

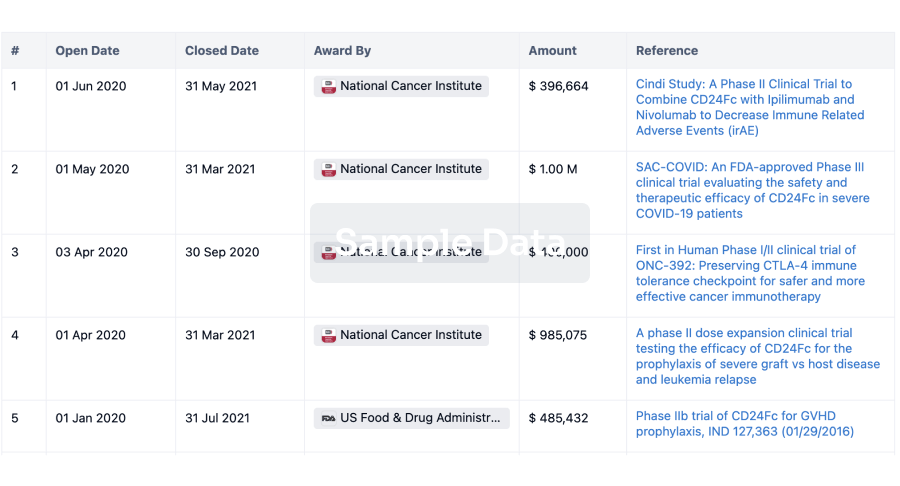

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

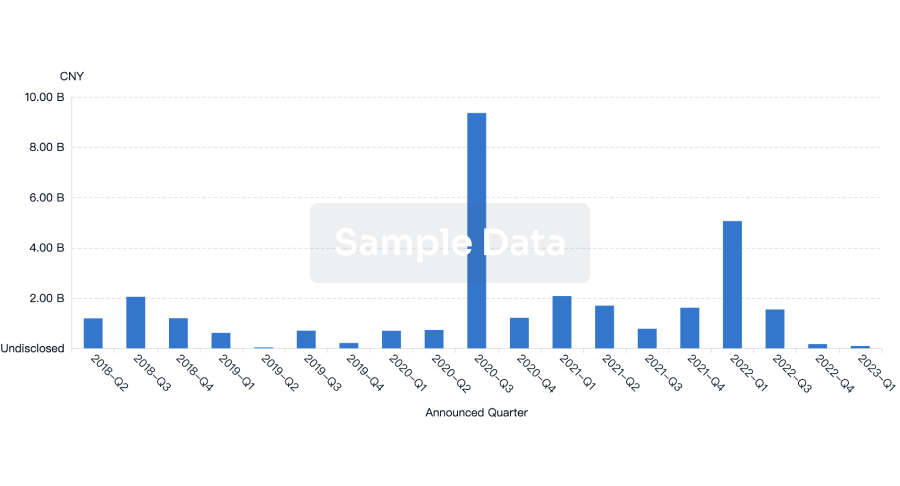

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

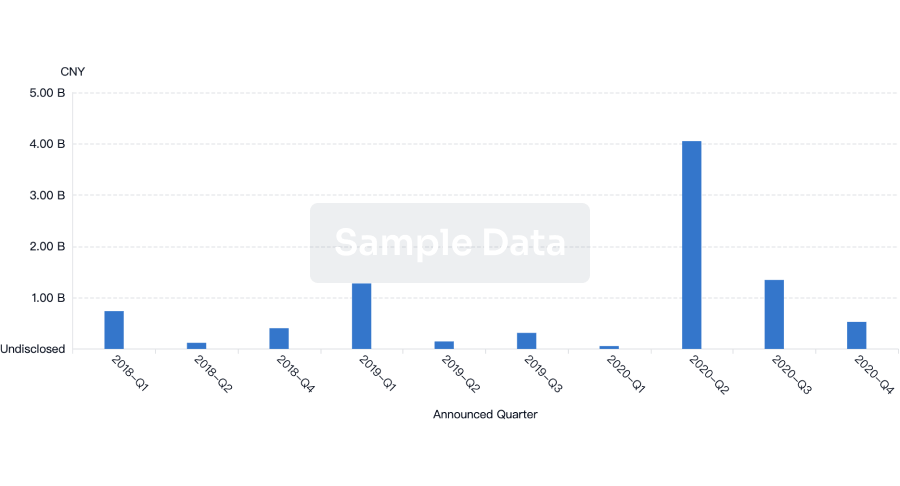

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free