Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Harvard Stem Cell Institute

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Harvard Stem Cell Institute

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Harvard Stem Cell Institute

Login to view more data

1,591

Literatures (Medical) associated with Harvard Stem Cell Institute02 Jun 2025·Journal of Experimental Medicine

Hiding in plain sight: A new lymphoid organ discovered in zebrafish

Article

Author: Langenau, David M. ; Bakr, Mohamed N.

01 May 2025·Molecular Metabolism

Renalase inhibition defends against acute and chronic β cell stress by regulating cell metabolism

Article

Author: Bonner-Weir, Susan ; Ryback, Birgitta ; Aparecida da Silva Pereira, Jéssica ; Mendez, Bryhan ; Yi, Peng ; Wei, Siying ; Arbeau, Meagan ; Weir, Gordon ; Ishikawa, Yuki ; Kissler, Stephan ; MacDonald, Tara L ; Cai, Erica P

01 May 2025·Laboratory Investigation

PRAME Expression in Melanoma is Negatively Regulated by TET2-Mediated DNA Hydroxymethylation

Article

Author: Fang, Rui ; Lian, Christine G ; Sorger, Peter K ; Draper, Elizabeth ; Wang, Justina ; Xu, Shuyun ; Pelletier, Roxanne ; Van Cura, Devon ; Vallius, Tuulia ; Fischer, Grant ; Alicandri, Francisco ; Mandinova, Anna ; Zhang, Arianna ; Katsyv, Igor ; Murphy, George F

37

News (Medical) associated with Harvard Stem Cell Institute29 Oct 2024

- First two out of three subjects treated with tegoprubart as part of immunosuppression regimen to prevent transplant rejection achieved insulin independence and remain insulin free, with glucose control in the normal range; Third subject was recently transplanted and is on trajectory for insulin independence - Islet engraftment in the first two subjects with tegoprubart estimated three to five times higher than engraftment in three comparable subjects receiving standard of care tacrolimus-based immunosuppression - Treatment with tegoprubart was generally well tolerated - Study data to be presented by UChicago Medicine’s team in oral presentation at the 5th IPITA/HSCI/Breakthrough T1D Stem Cells Summit IRVINE, Calif., Oct. 29, 2024 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Eledon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Eledon”) (NASDAQ: ELDN) today announced positive data for the first three islet transplant recipients treated with an immunosuppression regimen that includes tegoprubart, the Company’s investigational anti-CD40L antibody, for prevention of islet transplant rejection in subjects with type 1 diabetes (T1D). The investigator-initiated trial, conducted by the research team at the University of Chicago Medicine’s Transplantation Institute, demonstrated potentially the first human cases of insulin independence achieved using an anti-CD40L monoclonal antibody therapy without the use of tacrolimus, the current standard of care for prevention of transplant rejection. The first two subjects achieved insulin independence and normal hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) levels, a measure of average blood glucose, post-transplant. The third subject, who recently received an islet transplant, decreased insulin use by more than 60% three days following the procedure and continues on an insulin independence trajectory. Subjects on study received islet transplants combined with induction therapy, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and tegoprubart, given every third week by intravenous (IV) infusion. The first two subjects achieved insulin independence and presented stable islet graft function at approximately three months and six months post-transplant, respectively. Islet engraftment, measured by graft function standardized to the number of islets infused, was three to five times higher than three comparable subjects outside this study who received tacrolimus-based immunosuppression, suggesting treatment with tegoprubart is less toxic to transplanted islets resulting in improved graft survival and function. Treatment was generally well tolerated in all subjects with no unexpected adverse events or hypoglycemic episodes. After initial islet transplant, the first participant reduced insulin requirements by over 60% and normalized blood glucose control. The first patient then achieved insulin independence approximately two weeks after the second islet transplantation procedure. The data are being featured in an oral presentation at the International Pancreas and Islet Transplantation Association (IPITA), Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI), and Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF) 5th Annual Summit on Stem Cell Derived Islets on Tuesday, October 29, 2024. “We are very pleased that tegoprubart played a pivotal role in yet another landmark advance in transplantation research through the work of Dr. Witkowski, Dr. Fung and their team at UChicago Medicine,” said David-Alexandre C. Gros, M.D., Chief Executive Officer of Eledon. “Following promising results in kidney allotransplant procedures as well as heart and kidney xenograft procedures, these data from subjects following islet transplantation further demonstrate tegoprubart’s potential to protect transplanted organs and cells. Dr. Witkowski’s study also further reinforces prior study results showing that tegoprubart may offer a favorable safety and efficacy profile compared to tacrolimus-based immunosuppression regimens.” “These data are another step in our quest to achieve a path for functional cures in type 1 diabetes,” said Piotr Witkowski, M.D., Ph.D., Director, Pancreas and Islet Transplant Program, UChicago Medicine and one of the study’s lead investigators. “For more than 30 years, we have been looking for options that can deliver target levels of immunosuppression without the side effects associated with standard of care, including toxicity to the kidneys, central nervous system and islet cells, and increased risk of diabetes and hypertension. These data further support tegoprubart as a novel immunosuppression option that can play a central role in advancing islets transplantation as a potentially transformational alternative for subjects with type 1 diabetes.” “Breakthrough T1D is proud to fund and support this research and is encouraged by the tegoprubart study showing that subjects who received islet transplants with a tacrolimus-free immunosuppressive regimen are making insulin again,” said Breakthrough T1D Chief Scientific Officer Sanjoy Dutta, Ph.D. “Islet replacement therapies are a key priority for Breakthrough T1D, and we’re committed to driving research that moves us toward a world where these therapies are available to the broader T1D community. Achieving this goal requires novel approaches to keep transplanted cells functional with a tolerable immunosuppression regimen. These results are an important step toward that goal, and we look forward to seeing additional data.”

Efficacy and Safety Results The first participant was a 42-year-old female with a baseline weight of 88 kg/194 lbs (BMI of 30). At 90 days post-transplant, the participant’s HbA1c level improved to 6.0% (from 8.4% at baseline) and daily insulin dose decreased to 16 units per day (from 80 units per day at baseline). After 16 weeks, the participant received a second islet transplant, and approximately two weeks later achieved insulin independence, maintaining improved HbA1c levels of 5.4% afterwards. The second participant was a 30-year-old female with a baseline weight of 50 kg/110 lbs (BMI of 21). This patient stopped insulin support (from 60 units per day at baseline) four weeks after the islet transplant. Her HbA1c levels improved to 5.8% and below (from 8.5% at baseline) starting at seven weeks after the transplant. The third participant was a 37-year-old male with a baseline weight of 92 kg/203 lbs (BMI of 30) with a baseline HbA1C of 9.3%. This patient was discharged home on day three post-transplant, requiring 29 units of insulin (from 90 units per day at baseline). The treatment was generally well tolerated in all subjects with no unexpected adverse events, severe hypoglycemic episodes, or graft rejection. In January 2024, Eledon announced that it would be supplying tegoprubart for this investigator-led clinical trial with the UChicago Medicine Transplantation Institute for pancreatic islet transplantation in subjects with type 1 diabetes (NCT06305286). Tegoprubart is the cornerstone component of the chronic immunosuppressive regimen for trial participants and is being evaluated for the prevention of transplant rejection in the trial. Funding for the study includes grants from Breakthrough T1D (formerly known as JDRF) and The Cure Alliance. About Islet Transplantation for Type 1 Diabetes Pancreatic islet transplantation is a minimally invasive procedure developed to provide blood glucose control for subjects with type 1 diabetes and minimize or eliminate dependence on insulin. During the procedure, pancreatic islets containing insulin-producing beta cells are isolated from the pancreas of a deceased organ donor and infused through a small catheter into the patient’s liver. The islet cells lodge in small blood vessels in the liver and release insulin. Post-procedure, subjects remain on immunosuppression therapy to prevent transplant rejection. About Eledon Pharmaceuticals and tegoprubart Eledon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. is a clinical stage biotechnology company that is developing immune-modulating therapies for the management and treatment of life-threatening conditions. The Company’s lead investigational product is tegoprubart, an anti-CD40L antibody with high affinity for the CD40 Ligand, a well-validated biological target that has broad therapeutic potential. The central role of CD40L signaling in both adaptive and innate immune cell activation and function positions it as an attractive target for non-lymphocyte depleting, immunomodulatory therapeutic intervention. The Company is building upon a deep historical knowledge of anti-CD40 Ligand biology to conduct preclinical and clinical studies in kidney allograft transplantation, xenotransplantation, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Eledon is headquartered in Irvine, California. For more information, please visit the Company’s website at www.eledon.com. Follow Eledon Pharmaceuticals on social media: LinkedIn; Twitter Forward-Looking Statements This press release contains forward-looking statements that involve substantial risks and uncertainties. Any statements about the company’s future expectations, plans and prospects, including statements about planned clinical trials, the development of product candidates, expected timing for initiation of future clinical trials, expected timing for receipt of data from clinical trials, expected or future results of tegoprubart trials and its ability to prevent rejection in connection with islet cell transplantation or kidney transplantation, as well as other statements containing the words “believes,” “anticipates,” “plans,” “expects,” “estimates,” “intends,” “predicts,” “projects,” “targets,” “looks forward,” “could,” “may,” and similar expressions, constitute forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Forward-looking statements are inherently uncertain and are subject to numerous risks and uncertainties, including: risks relating to the safety and efficacy of our drug candidates; risks relating to clinical development timelines, including interactions with regulators and clinical sites, as well as patient enrollment; and risks relating to costs of clinical trials and the sufficiency of the company’s capital resources to fund planned clinical trials. Actual results may differ materially from those indicated by such forward-looking statements as a result of various factors. These risks and uncertainties, as well as other risks and uncertainties that could cause the company’s actual results to differ significantly from the forward-looking statements contained herein, are discussed in our quarterly 10-Q, annual 10-K, and other filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which can be found at www.sec.gov. Any forward-looking statements contained in this press release speak only as of the date hereof and not of any future date, and the company expressly disclaims any intent to update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. Investor Contact: Stephen JasperGilmartin Group(858) 525 2047stephen@gilmartinir.com Media Contact: Jenna UrbanBerry & Company Public Relations(212) 253 8881jurban@berrypr.com Source: Eledon Pharmaceuticals

Clinical ResultImmunotherapyClinical Study

01 Oct 2024

International diabetes pioneers and thought leaders from 11 countries will work with Biomea leadership to unlock the potential of menin science and beta cell biology to advance BMF-219 and Biomea’s evolving pipelineREDWOOD CITY, Calif., Oct. 01, 2024 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Biomea Fusion, Inc. (“Biomea”) (Nasdaq: BMEA), a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company dedicated to discovering and developing novel covalent small molecules to treat and improve the lives of patients with metabolic diseases, obesity and genetically defined cancers, today announced the formation of Biomea Fusion’s Global Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) with internationally renowned experts in beta cell science and diabetes therapeutics. The SAB will work closely with Biomea’s leadership team as they unlock menin science and beta cell biology to design disease modifying agents that address a root cause of diabetes – beta cell dysfunction. The SAB will also provide strategic guidance for the further clinical development of Biomea’s lead candidate BMF-219 – an investigational novel covalent menin inhibitor developed to regenerate, restore, and improve the health and function of insulin-producing beta cells. “We are excited to welcome these extraordinary and prestigious scientific leaders to the Biomea Scientific Advisory Board,” said Thomas Butler, CEO and Chairman of Biomea. “Each of these visionaries has made groundbreaking contributions to diabetes therapeutics and beta cell research. Together, they form a powerhouse of expertise and innovation for Biomea, which will be invaluable as we leverage our deep understanding of menin science to regenerate insulin-producing beta cells." Juan Pablo Frias, Chief Medical Officer and Head of Diabetes at Biomea said, “We are honored to convene a world-class SAB, that represents remarkable experience and knowledge across diabetes drug development, data-driven global clinical trial design, and beta cell biology. With our advisors’ leadership, expertise and collaboration, we will optimize our clinical development and commercialization path for BMF-219." “I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with Biomea since mid-2022, witnessing firsthand the groundbreaking FUSION platform poised to revolutionize beta cell science and the diabetes space,” said Rohit N. Kulkarni, M.D. Ph.D, Chair of Biomea’s SAB. “I am excited to lead this effort for Biomea and welcome this group of world-renowned leaders to Biomea's SAB at this crucial juncture in the company’s evolution. Together, we will start with taking a deep dive into the clinical data generated to date with BMF-219 and review the overall path towards commerciality. We will explore the potential for BMF-219 as a monotherapy as well as in combination with standard of care agents and provide our advice to the clinical and scientific team at the company. We look forward to further unlock the immense potential of menin science and islet cell biology.” The inaugural members of the Global Biomea SAB are listed below. Full biographies of SAB members can be found at https://biomeafusion.com/leadership/. Alex Abitbol, MD, is an accomplished endocrinologist and Assistant Medical Director at LMC Healthcare in Toronto, Ontario. He completed his medical education and specialized in Endocrinology and Metabolism at McGill University. Dr. Abitbol focuses on diabetes care and management, particularly applying technology to improve patient outcomes, including developing the artificial pancreas and automated insulin therapy. He is a principal investigator at Centricity Research, involved in clinical trials for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Board-certified in Internal Medicine and Endocrinology, Dr. Abitbol frequently speaks at conferences and is dedicated to advancing diabetes management technologies and patient care. Pablo Aschner Montoya, MD is an endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, serving as an Associate Professor of Endocrinology at Javeriana University School of Medicine in Bogotá, Colombia. He is also the Senior Research Advisor at San Ignacio University Hospital and the Scientific Director of the Colombian Diabetes Association. Dr. Aschner holds a medical degree from Javeriana University, specialized in internal medicine and endocrinology, and obtained a master’s in clinical Epidemiology. His research focuses on the prevention, diagnosis, control, and treatment of diabetes, emphasizing type 2 diabetes and its complications has significantly contributed to understanding diabetes care practices through influential studies like the International Diabetes Management Practices Study (IDMPS). He has held leadership roles in the Colombian Endocrine Society and the Latin American Diabetes Association (ALAD) and has been a member of the WHO Expert Advisory Panel and the IDF taskforce on Guidelines. Juliana Chan, MD is an endocrinologist, clinical pharmacologist and a diabetes researcher, currently serving as a Professor of Medicine and Therapeutics at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). She is the Founding Director of the Hong Kong Institute of Diabetes and Obesity and the CEO of the Asia Diabetes Foundation. Dr. Chan also directs the CUHK-PWH International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Centre of Education and Centre of Excellence in Diabetes Care. Dr. Chan's research focuses on the epidemiology, genetics, clinical trials and data-driven clinical management of diabetes. She established the Hong Kong Diabetes Register and developed the Joint Asia Diabetes Evaluation (JADE) Technology, a web-based platform used in 11 Asian countries. This innovative approach has enrolled over 120,000 patients with diabetes and significantly contributed to a decline in the death rate among people with diabetes in Hong Kong. Alice YY Cheng, MD is an endocrinologist and Associate Professor at the University of Toronto, specializing in endocrinology and metabolism at Trillium Health Partners and Unity Health Toronto. She completed her medical education at the University of Toronto in 1998 and has since become a leading expert in diabetes care. Dr. Cheng has been involved with the development of the Diabetes Canada clinical practice guidelines since 2003, serving as Chair for the 2013 version. She is past-Chair of the Professional Section of Diabetes Canada. Her contributions have earned her prestigious awards, including the Charles H. Best Award and the Gerald S. Wong Service Award from Diabetes Canada. In addition to her clinical work, Dr. Cheng served as the Chair of the Scientific Planning Committee for the American Diabetes Association (ADA) annual scientific sessions (2023-2024) and is an Associate Editor for the journal, Diabetes Care, and co-hosts the "Diabetes Care On-Air" podcast. Melanie Davies, MD, CBE, MB ChB, MD, FRCP, FRCGP, FMedSci is a highly esteemed endocrinologist and Professor of Diabetes Medicine at the University of Leicester. She directs the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre and the Patient Recruitment Centre Leicester. With over 25 years in diabetes research and clinical care, she has led numerous global clinical trials on diabetes, obesity, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Davies has published over 900 articles, significantly impacting international clinical guidelines for insulin and GLP-1 therapy. Her co-leadership at the Leicester Diabetes Centre has established it as a global leader in diabetes research and education. Honored as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) and elected Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences (FMedSci), Dr. Davies is recognized among the top 100 female scientists in the UK. Asma Deeb, MD, MBBS is a highly respected Consultant and Chief of Pediatric Endocrinology at Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City (SSMC) in Abu Dhabi, UAE. She is also a clinical professor at Khalifa University and Gulf University. Dr. Deeb trained in the UK, obtaining her MD from the University of Newcastle and specializing in Pediatric Endocrinology at the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on disorders of sexual differentiation, pediatric diabetes management technology, and diabetes genetics. She has published extensively and conducted significant studies on diabetes treatments and the effects of fasting during Ramadan on young diabetes patients. Dr. Deeb is the President of the Arab Society of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (ASPED) and has held leadership roles in several international pediatric endocrinology organizations. Her contributions have earned her numerous awards, including the Research Innovation Award from the Dubai Health Authority and the Technology Innovation Pioneer award from SEHA. Ralph A. DeFronzo, MD is a renowned endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, currently serving as Professor of Medicine and Chief of the Diabetes Division at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA) and Deputy Director of the Texas Diabetes Institute. He graduated from Yale University and earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, with further training in Internal Medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital and fellowships in Endocrinology and Nephrology. Dr. DeFronzo focuses on the pathogenesis and treatment of type 2 diabetes, particularly insulin resistance. He pioneered the euglycemic insulin clamp technique and played a key role in developing and obtaining FDA approval for metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors. He has received numerous prestigious awards, including the Banting Award and Claude Bernard Award, and published over 800 articles. His contributions have profoundly impacted diabetes understanding and management, influencing guidelines such as the ADA's 2022 Standards of Care. Thomas Danne, MD is a leading pediatric endocrinologist and diabetes expert who currently serves as the Chief Medical Officer International for JDRF (formerly JDRF) and as a Professor of Pediatrics at Hannover Medical School in Germany. He received his MD from the Medical School of the Freie University of Berlin and further enhanced his expertise through a Postdoctoral Fellowship at the German Research Council and a research fellowship at Harvard's Joslin Research Laboratory. He has held leadership roles in prominent organizations such as the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), the German Diabetes Association, and INNODIA. With over 700 publications and more than 19,000 citations, Dr. Danne has made a substantial impact on the field, leading the EDITION JUNIOR clinical trials and co-authoring the International Consensus on Time in Range. His innovative approaches, including color-coded charts for children, have improved diabetes care and management. Dr. Danne's significant contributions to diabetes research and care have earned him numerous accolades, including ISPAD Prizes for Innovation and Achievement, the Helmut-Otto Medal, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Diabetes Federation. Linda DiMeglio, MD, MPH is a celebrated pediatric endocrinologist and expert in type 1 diabetes research. She is the Edwin Letzter Professor of Pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, Division Chief of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology at Riley Children's Health in Indianapolis, and the co-director of Workforce Development for the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. Dr. DiMeglio graduated with honors from Harvard University and obtained her medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. She completed her residency at Children's Memorial Hospital (now Lurie Children’s) and a fellowship in pediatric endocrinology at Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, where she also earned a Master of Public Health degree. Her research focuses on type 1 diabetes prevention, beta-cell preservation, and new diabetes management technologies and therapeutics. Dr. DiMeglio has led numerous clinical trials contributing significantly to the understanding of beta-cell stress biomarkers. Steven V. Edelman, MD is a renowned endocrinologist and diabetes specialist, currently serving as a Professor of Medicine in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). He is also the founder and director of Taking Control of Your Diabetes (TCOYD), a not-for-profit organization dedicated to educating and empowering individuals with diabetes to manage their condition effectively. Dr. Edelman completed his medical education at the University of California, Davis, followed by a residency in internal medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He further specialized in endocrinology and metabolism during his fellowship at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston. His research interests include diabetes management, patient education, and the development of new therapies for diabetes. Dr. Edelman has been involved in numerous clinical trials and has published extensively in the field of diabetes care. Franco Folli, MD, PhD is an internist and diabetes researcher, currently a Professor of Endocrinology and Metabolism at the Department of Health Sciences, Universita’ degli Studi di Milano and affiliated with ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo in Milan, Italy. He earned his medical degree and Ph.D. from the Università di Milano. Dr. Folli's research focuses on inflammation, insulin signaling, and the pathophysiology of diabetes, significantly advancing the understanding of insulin resistance and inflammation in diabetes. Previously, he was a Professor of Internal Medicine (with tenure) at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, where he conducted groundbreaking clinical and basic research on diabetes. Supported by grants, from the Italian Ministry of Health, Telethon, National Institute of Health (USA), Dr. Folli has pioneered work on the molecular mechanisms of insulin action and resistance. Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD is an endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, currently Professor of Endocrinology and Chairman of the Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Bari Aldo Moro, and Chief of the Division of Endocrinology at University Hospital Policlinico Consorziale in Bari, Italy. He has held leadership positions, including President of the Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE) and Senior Vice President of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Dr. Giorgino has been also the Director of the Specialty School of Endocrinology and Metabolism at the University of Bari for several years, mentoring future endocrinologists. Dr. Giorgino research focuses on insulin resistance, beta-cell dysfunction, and the effects of diabetes drugs on pancreatic islets and the cardiovascular system. His notable studies include research on SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, impacting glycemic control and cardiovascular outcomes. Freddy Goldberg Eliaschewitz, MD is a prominent endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, currently the Director at CPClin Clinical Research Center in São Paulo, Brazil. He completed his medical degree and master's in Endocrinology at Universidade de São Paulo. Dr. Eliaschewitz has contributed significantly to clinical research and patient care at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo. His research focuses on diabetes, particularly glycemic control, insulin therapy, and preventing diabetic complications. He has led numerous clinical trials, including the GOAL study and IDMPS, exploring the efficacy of ultra-long basal insulins like degludec. Dr. Eliaschewitz has served as a consultant and advisory board member for major pharmaceutical companies and published extensively in peer-reviewed journals. His work on insulin therapy and diabetes management has advanced treatment practices, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Mohamed Hassanein, MD is a Senior Consultant in Endocrinology and Diabetes at Dubai Hospital, UAE, since 2014, and a Senior Lecturer and Associate Director for Postgraduate Diabetes Education at Cardiff University, UK, since 2007. He graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria, Egypt, and is renowned for his research on diabetes management during Ramadan. Dr. Hassanein has co-authored influential guidelines, including those for the American Diabetes Association and the IDF-DAR practical guidelines. He has published over 70 papers and presented at more than 50 conferences, focusing on the safety and efficacy of diabetes treatments, like SGLT2 inhibitors, during fasting. His research includes flash glucose monitoring and insulin pump therapy. Dr. Hassanein has been recognized with several awards, including the SAHF Lifetime Achievement Award in 2022. Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB is the Leonard L. Wright & Marjorie C. Wright Term Chair of Medicine and Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington (UW). He also serves as a Staff Physician at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and Director of the UW Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Kahn earned his medical degree from the University of Cape Town and completed his endocrine fellowship at UW. His research focuses on the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes, specifically islet beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. He has significantly contributed to understanding how islet amyloid formation leads to beta-cell loss and hyperglycemia. Involved in major clinical trials like the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) Study, Dr. Kahn has published over 730 peer-reviewed articles. He has received numerous awards, including the American Diabetes Association Outstanding Achievement in Clinical Diabetes Research Award and European Association for the Study of Diabetes Claude Bernard Award. He currently serves as editor-in-chief of Diabetes Care. Rohit N. Kulkarni, MD, PhD is a physician scientist and diabetes researcher, serving as a Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and holds the Diabetes Research and Wellness Foundation Chair. He is Co-Head of the Section on Islet and Regenerative Biology at the Joslin Diabetes Center, Principle Faculty of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and Associate Member of the Broad Institute. Dr. Kulkarni's research focuses on pathways in islet cell biology that are critical to understand the pathophysiology of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. His lab investigates growth factor receptors (e.g. insulin, IGF-1), mRNA modifications, and cross talk with incretin signaling. His lab has expertise in generating patient-derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells for differentiation into insulin- or glucagon-secreting cells for potential therapeutic applications. Dr. Kulkarni has received numerous accolades, including the Ernst Oppenheimer Award (Endocrine Society), the Albert Renold Prize (European Association for Study of Diabetes) and Paul E. Lacy Medal (Midwest Islet Consortium), and is an elected Fellow of the American Society for Clinical Investigation, the Association of American Physicians and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Chantal Mathieu, MD is a renowned endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, currently a Professor of Medicine at KU Leuven in Belgium and Chair of Endocrinology at University Hospital Gasthuisberg Leuven. She earned her M.D. and Ph.D. from the University of Leuven and trained in internal medicine and endocrinology there. Dr. Mathieu's research focuses on the prevention of type 1 diabetes, the effects of vitamin D on the immune system, and the functioning of insulin-producing beta cells. Notably, she coordinates the EDENT1FI project, a European initiative aimed at exploring screening strategies and early diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. She is Chair of the Board of the INNODIA initiative, a network of clinical trial sites for interventions in type 1 diabetes in Europe. Her contributions have earned her prestigious awards, including the InBev-Baillet Latour Prize for Clinical Research and the David Rumbough Award from the JDRF for her research on the pathophysiology of type 1 diabetes. Dr. Mathieu is also the President of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Jeremy Pettus, MD is an Associate Professor of Medicine in the Department of Endocrinology at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), where he specializes in diabetes care and research. After earning his medical degree from Boston University School of Medicine, he completed his residency and fellowship in Endocrinology at UCSD. Dr. Pettus is actively involved in clinical trials, focusing on new therapies for type 1 diabetes, including glucagon receptor antagonists and the development of the artificial pancreas. His work is widely recognized, and he is a frequent speaker at national and international conferences. In addition to his research, Dr. Pettus is committed to patient education through his involvement with the non-profit Taking Control of Your Diabetes (TCOYD), where he leads the Type 1 Diabetes track at national conferences. His clinical practice emphasizes personalized care, understanding the unique challenges faced by people with diabetes. With a focus on patient empowerment and innovative treatments, Dr. Pettus continues to make impactful contributions to the field of diabetes management. Julio Rosenstock, MD is a renowned endocrinologist and expert in type 2 diabetes, serving as the Director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City Dallas and Clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. He earned his medical degree from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and completed his residency and fellowship at UT Southwestern. Dr. Rosenstock's research focuses on novel therapeutic strategies for optimal glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. He has led numerous clinical trials, contributing to the development of new oral antidiabetic agents, incretin-based therapies, and insulin preparations. His recent work includes research on insulin icodec, a potential once-weekly basal insulin. Dr. Rosenstock holds leadership positions, including Senior Scientific Advisor for Velocity Clinical Research, and serves on advisory boards for pharmaceutical companies. Desmond Schatz, MD is a highly esteemed pediatric endocrinologist and expert in type 1 diabetes research. He serves as a Professor of Pediatrics and the Medical Director of the Diabetes Institute at the University of Florida (UF), as well as the Director of the Clinical Research Center within UF's Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI). Dr. Schatz earned his medical degree in South Africa. His research focuses on the prediction, natural history, genetics, immunopathogenesis, and prevention of type 1 diabetes, alongside developing new treatment strategies. He has been a key investigator in the Diabetes Prevention Trial and TrialNet and other multicenter studies. Dr. Schatz has received numerous accolades, including the Banting Award and JDRF's highest research award. He was honored with the UF College of Medicine Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020 and is a member of the Academy of Science and Medicine for Florida, and was a past president of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Jay S. Skyler, MD is a distinguished endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, currently a Professor of Medicine, Pediatrics, and Psychology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, where he also serves as Deputy Director for Clinical Research and Academic Programs at the Diabetes Research Institute. Dr. Skyler earned his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College and completed his training in Internal Medicine and Endocrinology at Duke University Medical Center. His research focuses on type 1 diabetes, particularly immune intervention strategies. He has led numerous clinical trials, including the NIH-sponsored Diabetes Prevention Trial for Type 1 Diabetes (DPT-1) and the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Clinical Trials Study Group. Dr. Skyler has received numerous awards, such as the Banting Medal, the Distinction in Endocrinology Award from the American College of Endocrinology, and the JDRF's Mary Tyler Moore/S. Robert Levine Award. Dr. Skyler has held leadership roles as President of the ADA, Vice-President of the International Diabetes Federation, and President of the International Diabetes Immunotherapy Group. He was the founding Editor-in-Chief of Diabetes Care and serves on multiple editorial boards. Kohjiro Ueki, MD, PhD is a distinguished endocrinologist and diabetes researcher, currently serving as the Director of the Diabetes Research Center at the National Center for Global Health, Japan. He also served as Professor of the Department of Molecular Diabetology, Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo where he earned his medical degree and PhD. Dr. Ueki's research focuses on insulin resistance, insulin secretion, and the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. He serves as the Chair of the Board of Directors of the Japan Diabetes Society and has been instrumental in developing clinical practice guidelines, including the "Kumamoto Declaration 2013". He has conducted significant studies on the efficacy and safety of diabetes treatments and the role of pancreatic alpha-cell function in insulin sensitivity. Supported by grants from prestigious organizations, Dr. Ueki has received numerous awards for his contributions. About COVALENT-111 COVALENT-111 is a multi-site, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase I/II study. In the completed Phase I portion of the trial, healthy patients were enrolled in single ascending dose cohorts to evaluate safety at the prospective dosing levels for type 2 diabetic patients. Phase II consists of multiple ascending dose cohorts and includes adult patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled by standard of care medicines. Once the Escalation Phase of COVALENT-111 was completed, the study advanced into an Expansion Phase (Ph IIb) consisting of multiple cohorts dosing type 2 diabetes patients for longer dose durations. Additional information about this Phase I/II clinical trial of BMF-219 in type 2 diabetes can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov using the identifier NCT05731544. About COVALENT-112 COVALENT-112 is a multi-site, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II study in adults with stage 3 type 1 diabetes. This stage describes the period following clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes when symptoms are present due to significant beta cell loss. COVALENT-112 will be a multi-arm trial comparing two different doses of BMF-219 to placebo (1:1:1) to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and durability of BMF-219 in adults with type 1 diabetes. Approximately 150 patients will be enrolled in the trial and will receive either BMF-219 or placebo over 12 weeks, followed by a 40-week off treatment period. This trial also includes an open-label portion for adults with type 1 diabetes up to 15 years since diagnosis. The open-label portion (n=40) is examining the efficacy, safety, and durability of BMF-219 at two oral dose levels, 100 mg and 200 mg over 12-week treatment followed by a 40-week off treatment period. Additional information about the Phase II clinical trial of BMF-219 in type 1 diabetes can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov using the identifier NCT06152042. About Biomea Fusion Biomea Fusion is a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the discovery and development of oral covalent small molecules to treat patients with metabolic diseases and genetically defined cancers. A covalent small molecule is a synthetic compound that forms a permanent bond to its target protein and offers a number of potential advantages over conventional non-covalent drugs, including greater target selectivity, lower drug exposure, and the ability to drive a deeper, more durable response. We are utilizing our proprietary FUSION™ System to discover, design and develop a pipeline of next-generation covalent-binding small molecule medicines designed to maximize clinical benefit for patients. We aim to have an outsized impact on the treatment of disease for the patients we serve. We aim to cure. Visit us at biomeafusion.com and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook. Forward-Looking Statements Statements we make in this press release may include statements which are not historical facts and are considered forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”), and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange Act”). These statements may be identified by words such as “aims,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “could,” “estimates,” “expects,” “forecasts,” “goal,” “intends,” “may,” “plans,” “possible,” “potential,” “seeks,” “will,” and variations of these words or similar expressions that are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Any such statements in this press release that are not statements of historical fact, including statements regarding expected contributions of our scientific advisory board, the clinical and therapeutic potential of our product candidates and development programs, including BMF-219, the potential of BMF-219 as a treatment for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, our research, development and regulatory plans, the progress of our ongoing and upcoming clinical trials, including our Phase I/II COVALENT-111 study of BMF-219 in type 2 diabetes, and our Phase II COVALENT-112 study of BMF-219 in type 1 diabetes, may be deemed to be forward-looking statements. We intend these forward-looking statements to be covered by the safe harbor provisions for forward-looking statements contained in Section 27A of the Securities Act and Section 21E of the Exchange Act and are making this statement for purposes of complying with those safe harbor provisions. Any forward-looking statements in this press release are based on our current expectations, estimates and projections only as of the date of this release and are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially and adversely from those set forth in or implied by such forward-looking statements, including the risk that we may encounter delays in preclinical or clinical development, patient enrollment and in the initiation, conduct and completion of our ongoing and planned clinical trials and other research and development activities. These risks concerning Biomea Fusion’s business and operations are described in additional detail in its periodic filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”), including its most recent periodic report filed with the SEC and subsequent filings thereafter. Biomea Fusion explicitly disclaims any obligation to update any forward-looking statements except to the extent required by law.

Executive Change

01 Jul 2024

Appointment of David Scadden, M.D. and Marella Thorell

Resignation of Regina Hodits and Björn Odlander

PHILADELPHIA, July 1, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Carisma Therapeutics Inc. (Nasdaq: CARM) ("Carisma" or the "Company"), a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on discovering and developing innovative immunotherapies, today announced the appointment of Marella Thorell and David Scadden, M.D., to the Company's Board of Directors, effective June 30, 2024. Additionally, Regina Hodits and Björn Odlander have informed the Board of their intention to step down as members effective June 30, 2024, due to other professional commitments.

"We are pleased to welcome David and Marella to the Carisma Board of Directors. Their vast experience in the life sciences sector will be instrumental in advancing our cell therapy platform focused on engineered macrophages," said Sanford Zweifach, Chair of the Carisma Board of Directors. "We would also like to thank Regina and Björn for their invaluable contributions, guidance, and leadership throughout their tenure. We wish them the utmost success in their future endeavors."

"Dr. Scadden's renowned expertise as a physician and medical researcher will be incredibly valuable to Carisma, and we are honored to welcome him to our Board of Directors. Ms. Thorell's experience as a public company executive and Board Member of biotech companies will enhance the business capabilities of our Board," said Steven Kelly, President and Chief Executive Officer of Carisma. "These new appointments enrich our Board's diversity of experience and perspective, providing exemplary leadership as we work with urgency to bring groundbreaking immunotherapies to patients."

About David Scadden

Dr. Scadden is the Gerald and Darlene Jordan Professor of Medicine and Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University. Dr. Scadden founded and directs the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and co-founded and co-directs the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. Dr. Scadden is Chairman Emeritus and Professor of the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology. Dr. Scadden has received numerous honors and awards and has served on the board of scientific counselors for the National Cancer Institute, the board of external experts for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the board of directors of the International Society for Stem Cell Research and is an affiliate member of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. He serves on multiple editorial boards, scientific advisory boards, and corporate boards. He is a scientific founder of Fate Therapeutics, Inc., and Dianthus Therapeutics, Inc., and also serves on the Board of Directors of Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Editas Medicine, Inc. Dr. Scadden received a bachelor's degree in English from Bucknell University and an M.D. from Case Western Reserve School of Medicine.

About Marella Thorell

Marella Thorell brings more than 25 years of extensive experience in finance and operations across both public and private biotech companies. Ms. Thorell is currently the Chief Financial Officer of Seres Therapeutics. Previously, she served as the Chief Financial Officer of Evelo Biosciences. Her prior roles include Chief Accounting Officer at Centessa Pharmaceuticals, Chief Financial Officer of Palladio Biosciences prior to its acquisition by Centessa, and Chief Financial Officer and Chief Operating Officer of Realm Therapeutics. Before her time at Realm Therapeutics, Ms. Thorell held positions of increasing responsibility at Campbell Soup Company and Ernst & Young, LLP. Ms. Thorell is a Director and Chair of the Audit Committee of ESSA Pharmaceuticals and was previously Chair of the Board of Vallon Pharmaceuticals before its merger in 2023. Ms. Thorell received a bachelor's degree in business from Lehigh University.

About Carisma

Carisma Therapeutics Inc. is a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on utilizing our proprietary macrophage and monocyte cell engineering platform to develop transformative immunotherapies to treat cancer and other serious diseases. We have created a comprehensive, differentiated proprietary cell therapy platform focused on engineered macrophages and monocytes, cells that play a crucial role in both the innate and adaptive immune response. Carisma is headquartered in Philadelphia, PA. For more information, please visit .

Investors:

Shveta Dighe

Head of Investor Relations

[email protected]

Media Contact:

Julia Stern

(763) 350-5223

[email protected]

SOURCE Carisma Therapeutics Inc.

Executive ChangeCell TherapyImmunotherapy

100 Deals associated with Harvard Stem Cell Institute

Login to view more data

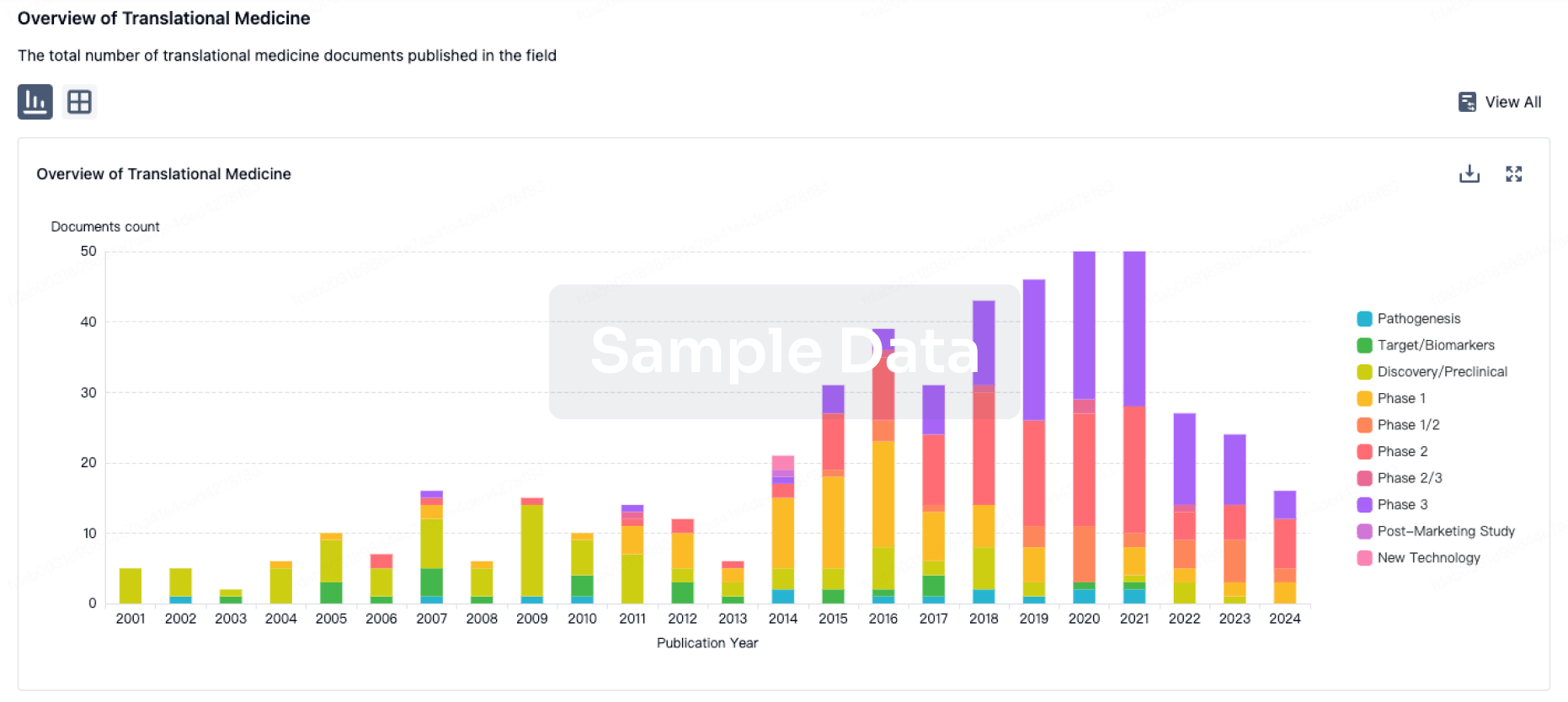

100 Translational Medicine associated with Harvard Stem Cell Institute

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 08 Jul 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

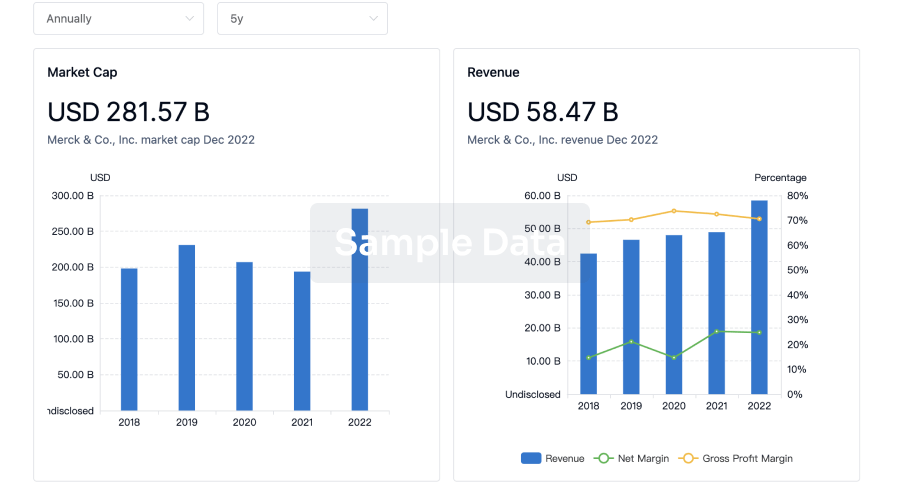

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

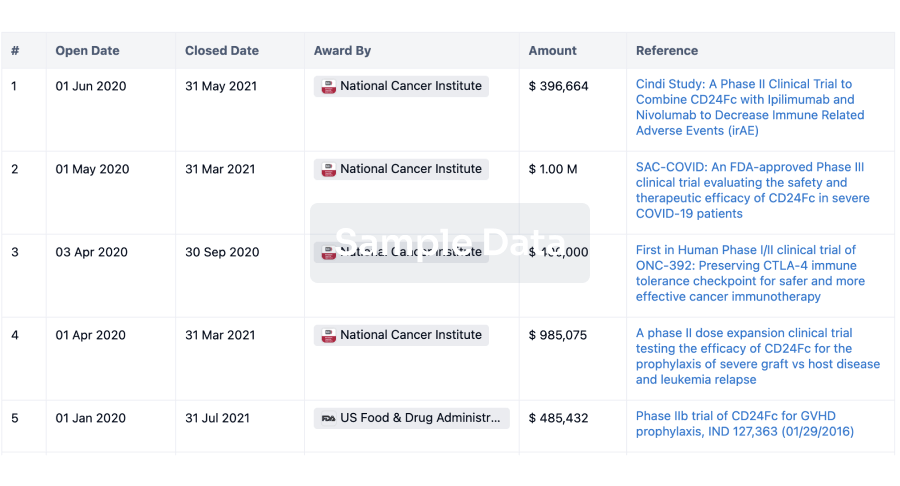

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

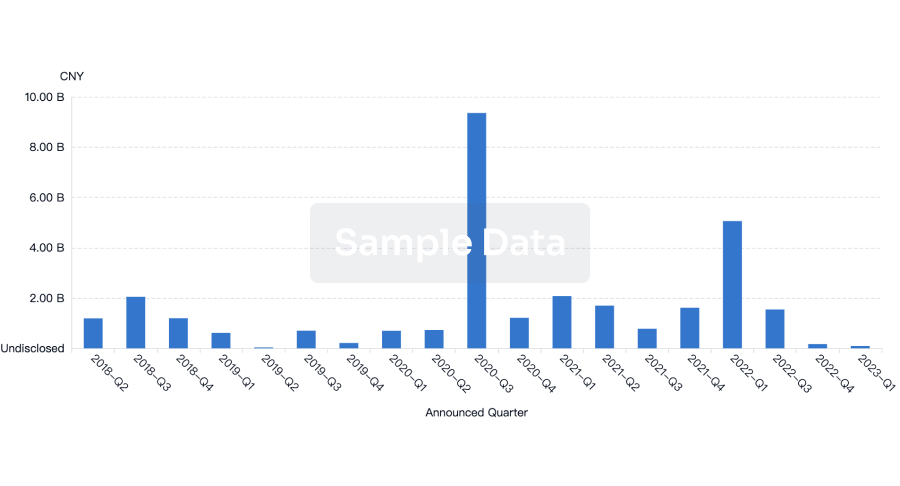

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

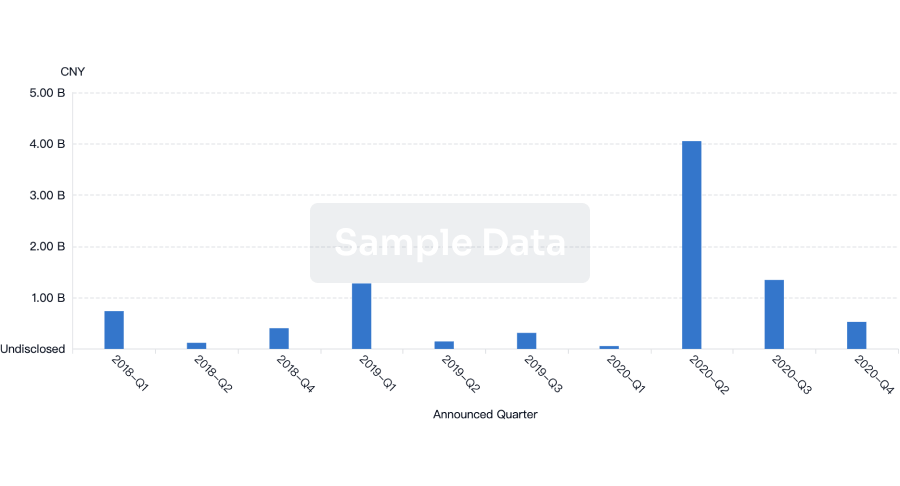

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free