Request Demo

Last update 29 Aug 2025

Biopharma

Last update 29 Aug 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Biopharma

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Biopharma

Login to view more data

415

News (Medical) associated with Biopharma21 Aug 2025

Pharma companies have pledged at least $292 billion to expand their US production footprints since early this year, as Johnson & Johnson added detail on how it will spend part of its multibillion-dollar promise it made in March.

Companies have been making an effort to reshore their manufacturing to the US since President Donald Trump threatened tariffs on pharma goods. These expansion budgets are spread out over several years by as much as a decade. Some of it may not come to fruition, and others’ pledges include ones

from previously announced plans

that predate Trump’s return to office.

Johnson & Johnson

said

Thursday that $2 billion is allocated for a new factory in Holly Springs, NC. The 160,000 square-foot factory will be at Fujifilm’s new biopharmaceutical manufacturing site and will create around 120 new jobs. This $2 billion budget will be made over the next decade.

J&J said it will share further plans for new builds and other expansions in the US in the coming months. The pharma company is continuing to work on building a

biologics site in Wilson, NC

, which was announced in October 2024.

Trump has been using the threat of pharma tariffs as an incentive for companies to move drug production to the US. His most recent comments in early August warn these levies could arrive in

“the next week or so,”

but they have yet to show up.

Meanwhile, Trump has revealed more details on his “most favored nation” policy on Thursday, which will

tax generic pharma goods

from the EU, as a part of the US-EU trade deal. Trump recently ordered health officials to create a

six-month stockpile

for APIs for 26 “critical” drugs.

06 Aug 2025

iStock,

SergeyNivens

From tariffs to drug pricing to the FDA, biopharma CEOs find themselves pulled into policy discussions on this year’s second quarter earnings calls.

President Donald Trump has been re-raising many issues that pharmaceutical CEOs were happy to have left behind in the first quarter as earnings reporting season continues. Across the pharma landscape, CEOs are doing their best to project the idea that there is nothing to worry about as the pressure from Washington grows.

Last week, the president sent a round of

letters to a batch of pharma CEOs

, asking them to get to work implementing Most Favored Nation drug pricing. Tariffs of 15% were

placed on Europe

, which could have implications on the industry, while the president threatened tariffs

as high as 250%

on imported pharmaceutical products specifically—although not any time soon. Then there was the high-profile

resignation

of an FDA official

, which some reports say can be traced all the way back to the White House.

Inevitably, these issues were raised as companies reported second quarter earnings over the past week.

On the CEO Letters

Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla couldn’t dodge the

questions about those letters

. Analyst after analyst tried to chip away at Bourla’s well-trained responses, seeking any inkling of how the high-pro leader is faring in discussions with the president.

“I’m happy the way that they listen to us, in the way that we are trying collectively to find solutions that, from one hand, could make medicines affordable in the U.S., on the other hand, will make our industry even more competitive compared to China,” Bourla said.

Bourla was one of very few pharma CEOs who was personally named by the president in the letters. While most were the same, Bourla’s had his full name scratched out and his first name written, apparently in Trump’s handwriting. This signaled to analysts that he had a close connection with the president, which traces back to Pfizer’s Operation Warp Speed effort to develop the COVID-19 vaccine during the pandemic. Bourla confirmed that he had spoken directly to Trump to discuss the matters in the letter.

But who is Trump’s closest pharma pal? If you ask

Regeneron

CEO Leonard Schleifer, it isn’t him. Queried about the president’s personalization of the letters, Schleifer said he hasn’t been to Washington lately to discuss drug pricing or other issues. The Regeneron chief executive was asked if he, or any of his peers at Eli Lilly or Pfizer, might have some sway over policy these days.

“I think the president probably knows Regeneron and my first name, given that it was Regeneron’s cocktail for COVID that may have saved his life,” Schleifer said. “Beyond that, I don’t have any great insights to the policies.”

His counterparts at Lilly and Pfizer have been more active in attempting to influence policy at this time, Schleifer added. Bourla confirmed as much in his earnings comments days later, while Lilly has yet to report.

On the specifics of the drug pricing plan, Schleifer said he agrees with the president that European nations are not paying their fair share for drugs. He said to change this “complicated” reality, policy and trade need to be adjusted, because companies can’t do it alone.

“American consumers should not be paying for all of the innovation. The solution is simply not to lower prices in the U.S. without some equilibrating in Europe because then there’ll be no innovation,” Schleifer said.

AstraZeneca’s Pascal Soriot agreed, saying that his company has been

lobbying the Trump administration

and offering some policy proposals that could achieve what the president is trying to do. But he also noted that access to new medications needs to be considered as the pricing discussion continues.

“In many countries in Europe, patients wait for years to get access to medicines that could save their lives,” Soriot said on AstraZeneca’s earnings call last week.

AbbVie’s

Robert Michael, meanwhile, credited the president’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act with expanding the orphan drug exemption to the benefit of cancer therapy Venclexta. Michael said the company had assumed that drug would be subject to price negotiations soon under the Inflation Reduction Act, but with the change in the newer bill, Venclexta is not expected to be subject.

“That’s an example of a good policy change where innovation is being rewarded and not penalized,” Michael said during AbbVie’s call last week.

On FDA Disruption

If anyone has insight into the inner workings of the FDA drug approval machine right now, it’s Moderna’s regulatory team. On a

Friday earnings call

, President Stephen Hoge said the company was pleased with the three approvals they received in the past quarter.

“I will note that they happened on time, and that was through the incredibly diligent work of the folks at FDA to conduct those reviews in a rigorous way, and we continue to feel that those productive dialogues are going on now even on our existing files for the seasonal update,” he said.

Hoge pledged to work closely with the FDA to transparently respond to any questions, even after the much-publicized changes within the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), and the CDC, including at the agency’s

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

. When any questions are received by the agencies to help inform public health, Hoge said that Moderna will make sure to provide that information.

On Tariffs

Many CEOs—of Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Moderna, Takeda, Regeneron and many more—brushed off the threat of tariffs to the pharmaceutical industry, especially for near term impacts this year. There’s still too much uncertainty on what exactly will be taxed, so the executives weren’t willing to speculate.

But AbbVie’s Michael went a bit further, noting that one of his company’s largest products, Skyrizi, is made in the U.S. for the domestic market. Longer term, AbbVie plans to add even more U.S. manufacturing capacity, as part of a $10 billion capital investment announced on last quarter’s earnings call. This would include four sites for active pharmaceutical ingredients, peptide dug products and devices.

Otherwise, Michael, like his fellow CEOs, will wait for the Section 232 process to complete before commenting further on how tariffs will impact AbbVie.

Merck’s

Robert Davis

took a shot at providing some clarity to analysts about what a 15% tariff would be like for the Keytruda-maker. While he wouldn’t give specific guidance, he said that if 15% tariffs were implemented today, the impact would be minimal as Merck has conducted inventory management and moved manufacturing to the U.S. already.

Similarly, AstraZeneca CFO Aradhana Sarin explained that since the first quarter, the company has been managing the potential tariff impact through inventory. AstraZeneca is also starting tech transfers for some products that are not currently manufactured in the U.S. Still, Sarin expects little impact.

For its part, Pfizer included potential impacts of Most Favored Nation drug price changes and tariffs in its guidance this quarter—specifically factoring in the currently implemented tariffs on Canada, China and Mexico—but declined to provide actual numbers, to the chagrin of analysts on the call. Bourla, like his fellow pharma execs, said that Pfizer will await the conclusion of the Section 232 investigation before elaborating on tariffs’ impact to the company, though he did note that Pfizer is talking with trade officials about tariffs.

Vaccine

29 Jul 2025

With 30K+ users in the past month alone, pRxEngage is turning discovery into action, making clinical trial access smarter, more personal, and more human.

We’re not here to replace the clinical trial recruitment process, we’re here to make it more relatable, understandable, and a real option that supports people's health journey.”

— Keith Berelowitz

ATLANTA , GA, UNITED STATES, July 29, 2025 /

EINPresswire.com

/ -- In less than three months from launch, pRxEngage is already reshaping how patients and communities engage with clinical research. The AI-powered, behavioral science-driven platform has initiated thousands of clinical trial discovery journeys, listed trials across six continents, and attracted growing interest from global biopharma, CROs, research sites, and community groups. Most significantly patients are engaging and finding clinical trials they want to be part of.

Unlike platforms that search for problems after building a solution, pRxEngage was built from the ground up to address the root causes of clinical trial exclusion, complexity, and mistrust.

“We built this because trial recruitment has not kept up with the world we live in today and patients are tired of being treated like data points,” said Keith Berelowitz, Founder and CEO of pRxEngage. “Our goal is to replace confusion with clarity, friction with flow, and fear with trust.”

The Challenge and the Opportunity

• $2.6B+: average cost to bring a drug to market¹

• 80% of trials miss enrollment targets²

• 30% dropout rates are typical³

• Yet, over 80% of patients would participate if trials were easier to find and understand⁴

With the widening

NIH funding gap

making it harder for U.S.-based research to remain accessible, especially for underserved communities. pRxEngage helps fill that gap by creating more inclusive, community-based pathways into research, ensuring that progress doesn’t leave patients behind. These pathways are replicated globally, with the platform and its easy to understand clinical trial information and self service assessment tools being available to view in 45 languages in countries worldwide. This is a platform focused on connecting the right patients to the right research wherever that may be.

To better understand what stands between willingness and participation, pRxEngage conducted a survey of 157 patients across the UK, USA, Canada, and Europe.

The findings reinforced what the industry often underestimates:

• 80.6% said they are willing to join a clinical trial

• Yet only 30.6% actually have

This gap isn’t about fear or lack of motivation. It’s driven by real-world, addressable barriers:

• 51% cited travel distance as a major obstacle

• 51% pointed to strict eligibility criteria

• 43% didn’t know where to look

• 32% found trial information complex or unclear

• 32% were concerned about potential side effects

“Too often, we assume patients are unwilling when they’re actually unsupported,” said Berelowitz. “This is exactly why our platform exists to turn intent into action by removing the friction that holds people back from participating in research.”

AI Where It Works. Humans Where It Matters.

pRxEngage blends AI-driven matching with behavioral science and real human support. The platform guides patients toward suitable studies while preserving the essential role of physicians, coordinators, and advocates in building trust.

“AI should never replace empathy. But it can remove noise, eliminate delays, and support better matches,” said Berelowitz. “We’ve designed pRxEngage to know when to lead and when to get out of the way.”

Making Trials Familiar Through a Dating App Lens

To make clinical trials more accessible, pRxEngage draws from a universally understood model: dating apps.

“Most people don’t know what a clinical trial really is,” said Berelowitz. “But many know what it means to swipe, explore, and evaluate fit. That’s exactly how clinical trial discovery should feel.”

As one new user put it:

“It felt a bit like a dating app, especially the way it got my attention. You got me to look, and then took the fear away. That’s what made me stay on the site.”

This is not about trivializing research, it's about normalizing participation.

Platform Growth and Reach (as of July 2025)

• Over 10,000 clinical trials listed currently seeking patients across a wide variety of medical conditions

• Over 31,000 unique visitors to the platform in under one month

• Trials listed across North America, UK, Europe, South America, Africa, and Southeast and East Asia

• 67% of traffic from organic and peer referrals

• 42% of patients return to explore additional studies

• Thousands of patient journeys initiated

Leadership Expansion and Strategic Traction

To accelerate scale and execution, pRxEngage has strengthened its leadership team with proven operators across health tech, biotech, and SaaS:

David Guthrie, CTO of REPAY and former CTO at Sharecare, WebMD, and PGi, has joined the Board, bringing his wealth of experience to support the technical team and provide his unique insights.

“I’m excited to help improve healthcare access by leveraging pRxEngage’s model, using cloud and AI to remove barriers and connect patients with life saving opportunities,” said Guthrie.

Daniel Graff Radford, a seasoned CEO with a track record of scaling and transforming technology platforms, also joins the Board. He brings deep expertise in product strategy, commercial execution, and long term growth.

Jeffrey Cehelsky joins as Chief Biopharma Strategy & Solutions Officer. With decades of experience at companies including Millennium (Takeda), Alnylam, and Intellia, Cehelsky brings deep expertise in biotech commercialization and clinical operations.

Wain Kellum, CEO of Canto, joins as a strategic advisor with a legacy of scaling global SaaS companies. His leadership experience and operational insights complement the lived experience embedded throughout the pRxEngage team.

These appointments reinforce pRxEngage’s commitment to meets the needs of all stakeholders; patients, sponsors, sites, and community partners with rigour, empathy, and purpose.

Importantly, pRxEngage is not just built for patients but with them. Patients power the organization from within, holding significant roles across product, operations, and strategy. Their lived experience is embedded in every layer of the platform, ensuring it remains grounded, human-centered, and accountable to the communities it serves.

Backed by Belief, Not Buzzwords

Following a significantly oversubscribed seed round, pRxEngage turned away further capital to stay lean and focused. In a market that now demands real-world ROI, the platform’s additive yet disruptive approach is resonating with sponsors, sites, and community partners and most significantly patients.

“We chose to cap our round not out of caution, but conviction and to stay lean and focused” said Berelowitz. “The capital we raised gives us a long runway and the freedom to continue to build on what matters: a platform that is already attracting high numbers of patients and a pipeline of AI assisted and behaviorally driven tools and features that truly serve patients and the stakeholders that make up the clinical trial ecosystem.”

What sits at the heart of the mission is the impact the platform can have on delivering hope to patients through awareness and accessibility of clinical trials. Berelowitz went on to add, “We are not here to replace the clinical trial recruitment process. We are here to make it more relatable, understandable, and a real option that supports people's health journey.”

About pRxEngage

pRxEngage is a patient-powered clinical research platform that uses AI and behavioral science to help patients discover and connect with trials that genuinely fit their lives. The platform supports sponsors, sites, and community groups with a more inclusive, effective approach to participant engagement and retention across the clinical trial journey,

www.prxengage.com

.

References

1. Deloitte. (2025, March 25). Global pharma R&D returns rise.

2. Kalyva, M., et al. (2025). JMIR Formative Research, 9, e55513.

3. ACRP. (2023, February 22). Unique Considerations for Patient Retention.

4. Clinical Leader. (2024, March 20). CISCRP Patient Survey.

Keith Berelowitz

pRxEngage

info@prxengage.com

Visit us on social media:

LinkedIn

Instagram

Facebook

YouTube

TikTok

X

Connecting patients, researchers & advocates worldwide with one mission: making clinical trial discovery as easy and intuitive as finding your next match.

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability

for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this

article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Executive ChangeClinical Study

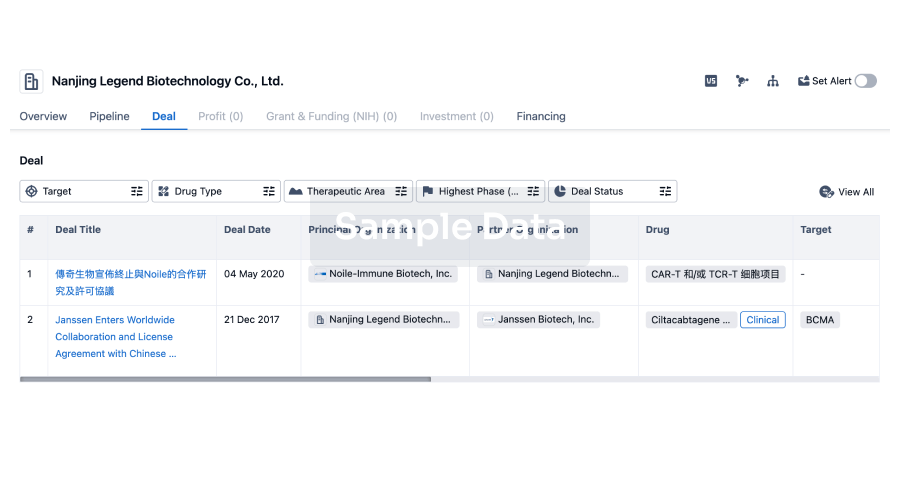

100 Deals associated with Biopharma

Login to view more data

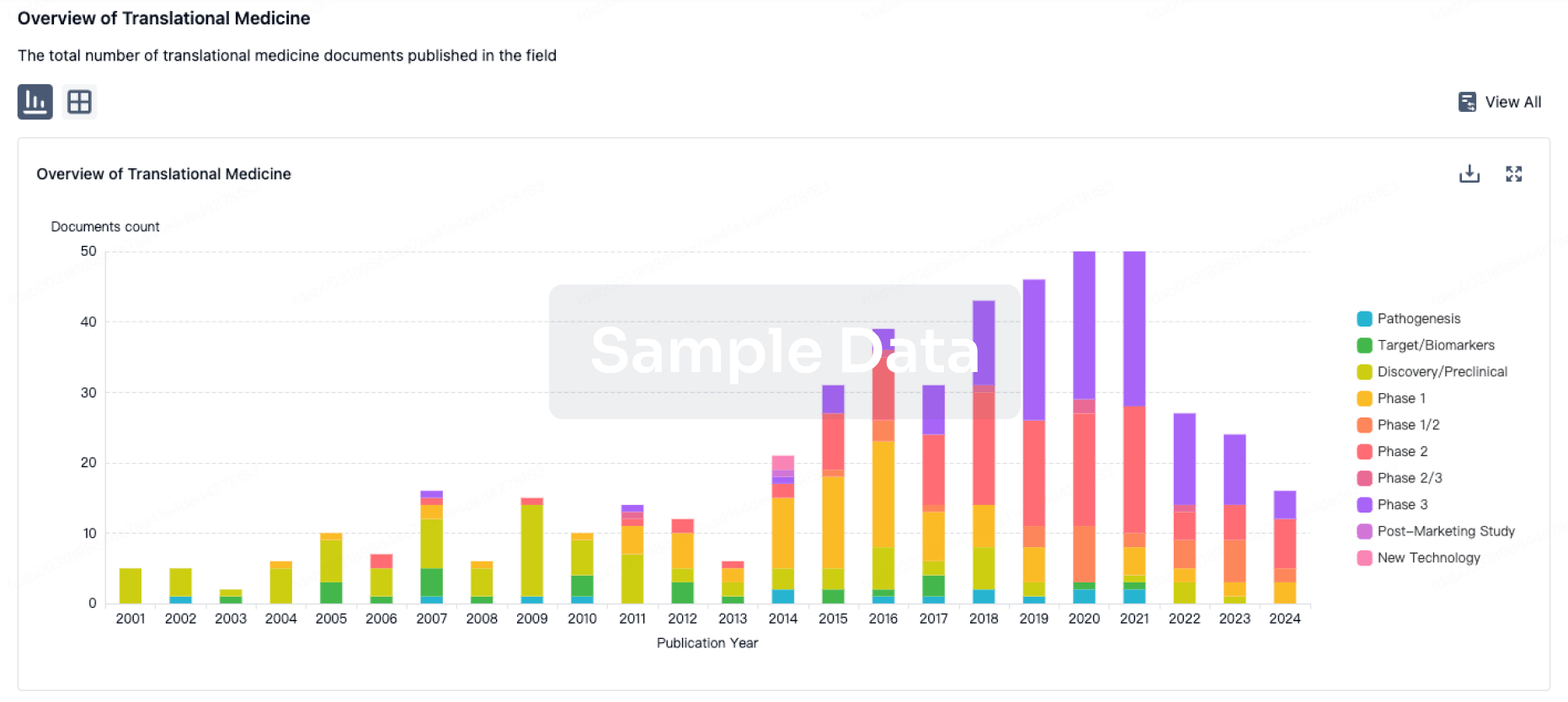

100 Translational Medicine associated with Biopharma

Login to view more data

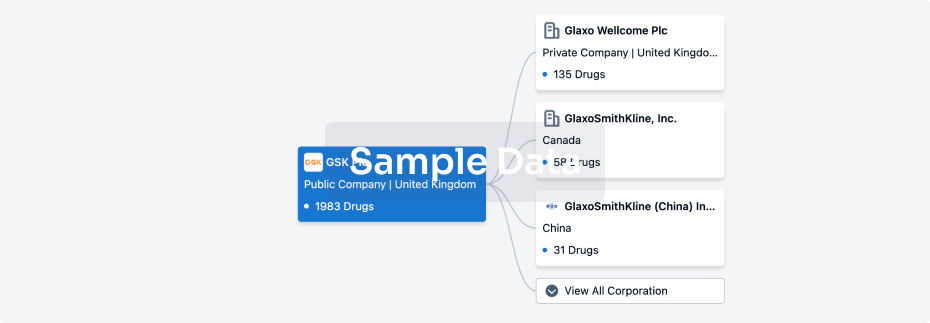

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 30 Oct 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

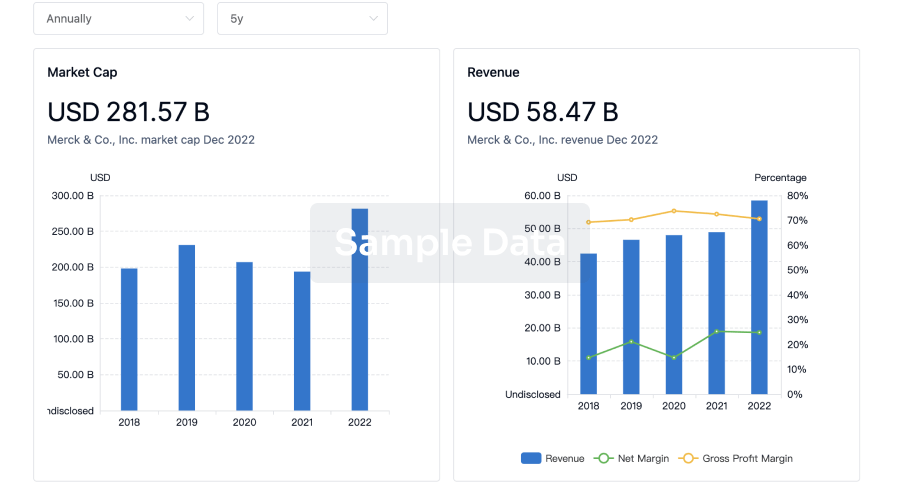

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

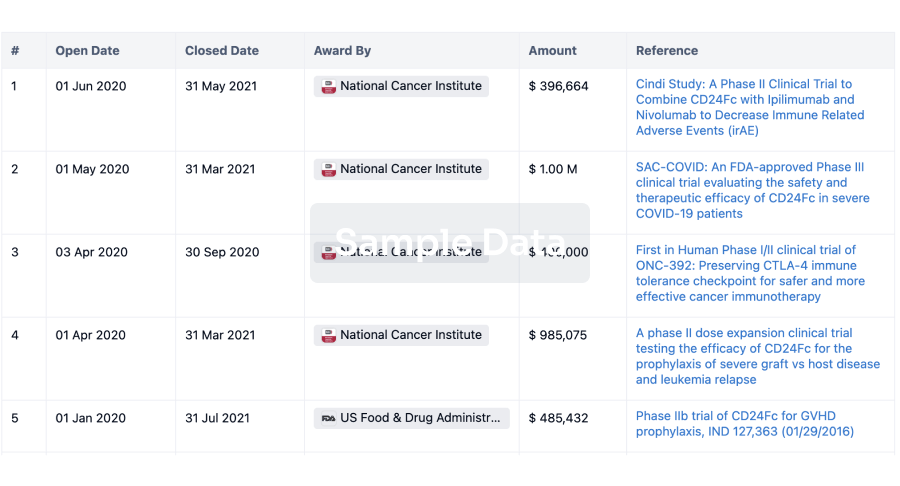

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

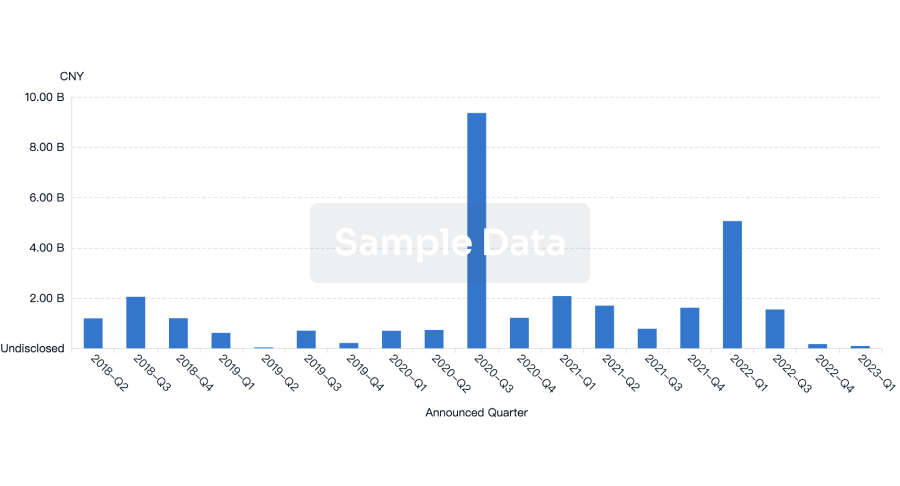

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

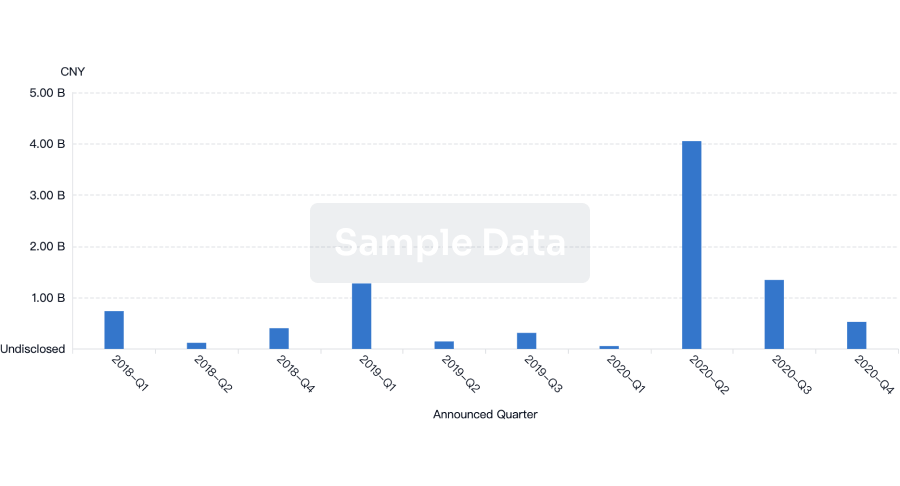

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free