Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Artis

Private Company|Russia

Private Company|Russia

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with Artis

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Artis

Login to view more data

90

News (Medical) associated with Artis06 Feb 2025

Published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, the study showcases the potential of AI-powered heart sound analysis to transform early detection and management of pulmonary hypertension.

SAN FRANCISCO, Feb. 6, 2025 /PRNewswire/ --

Eko Health, a leader in applying artificial intelligence (AI) for the early detection of heart and lung diseases, today announced publication of a peer-reviewed study evaluating its novel algorithm for the detection of pulmonary hypertension (PH). The study, which was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA), highlighted the algorithm's ability to analyze heart sounds recorded with a digital stethoscope for identifying elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressures, a key indicator of PH.

Continue Reading

Published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, the study showcases the potential of AI-powered heart sound analysis to transform early detection and management of pulmonary hypertension.

The study underscores the potential of this non-invasive, rapid detection tool to aid clinical decision-making in primary care and other settings where costly or invasive diagnostic methods are less accessible. Additionally, the algorithm demonstrated its ability to pinpoint specific, clinically relevant segments of heart sound recordings, offering a transparent and explainable AI approach that aligns with physicians' diagnostic workflows.

"This innovative approach demonstrates how combining digital stethoscopes with advanced AI can lead to a low-cost, non-invasive, point-of-care screening tool for the early detection of pulmonary hypertension," said Dr. Gaurav Choudhary, Lead Principal Investigator, and Ruth and Paul Levinger Professor of Cardiology and Director of Cardiovascular Research at Brown University Health and the Alpert Medical School of Brown University. "Our findings represent a significant advancement in clinical practice that can ultimately enhance patient care."

The study utilized 6,000 heart sound recordings paired with echocardiographic pressure estimates to train the AI model. The algorithm demonstrated strong performance, with an average area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve of 0.79, a sensitivity of 71%, and a specificity of 73%. Ongoing data collection from over 1,200 patients continues to refine the model's accuracy and clinical utility, with the goal of further improving detection capabilities for broader clinical use.

"These encouraging results highlight Eko Health's unwavering commitment to advancing innovation in cardiopulmonary health," said Dr. Steve Steinhubl, Chair of Eko's Scientific Advisory Board and Cardiologist and Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Purdue University. "The company's goal is to develop pioneering AI solutions that address significant gaps in healthcare delivery. Early detection and intervention are essential in addressing cardiovascular diseases, and Eko is dedicated to providing accessible and scalable technologies that empower healthcare providers while improving patient care globally."

Pulmonary hypertension, characterized by elevated pressure in the blood vessels connecting the heart and lungs, places significant strain on the heart and can lead to heart failure, early disability, or mortality if left untreated. Despite being a serious condition, PH is often underdiagnosed due to the limited availability of effective detection tools. The condition is also present in people with heart and lung diseases and is estimated to impact up to 10% of people aged 65 and older globally, with millions more affected under the age of 65. Alarmingly, in severe cases, it can take over two years from the onset of symptoms to receive a proper diagnosis.²

Eko's algorithm was partially funded through a $2.7 Million Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to Eko and Dr. Choudhary. The funding supported a collaboration with Brown University Health System's Cardiovascular Institute, enabling research into innovative early detection methods for conditions that demand timely intervention.

For more insights into Eko Health and its portfolio of transformative cardiopulmonary solutions, please visit .

About Eko

Eko Health is a leading digital health company advancing how healthcare professionals detect and monitor heart and lung disease with its portfolio of digital stethoscopes, patient and provider software, and AI-powered analysis. Its FDA-cleared platform, used by over 500,000 healthcare professionals worldwide, allows them to detect earlier and with higher accuracy, diagnose with more confidence, manage treatment effectively, and ultimately give their patients the best care possible. Eko Health is headquartered in Emeryville, California, with over $165 million in funding from ARTIS Ventures, DigiTx Partners, Double Point Ventures, EDBI, Highland Capital Partners, LG Technology Ventures, Mayo Clinic, Morningside Technology Ventures Limited, NTTVC, Questa Capital, and others.

About Brown University Health

Formed in 1994, Brown University Health is a not-for-profit health system based in Providence, R.I. comprised of three teaching hospitals of The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University: Rhode Island Hospital and its Hasbro Children's Hospital; The Miriam Hospital; and Bradley Hospital, the nation's first psychiatric hospital for children; Newport Hospital, a community hospital offering a broad range of health services; Gateway Healthcare, the state's largest provider of community behavioral health care; Brown Health Medical Group, the largest multi-specialty practice in Rhode Island; and Brown Health Medical Group Primary Care, a primary care driven medical practice. Brown University Health teaching hospitals are among the country's top recipients of research funding from the National Institutes of Health. The hospitals received over $145 million in external research funding in fiscal 2023. All Brown University Health-affiliated partners are charitable organizations that depend on support from the community to provide programs and services.

Media Contact:

Sam Moore

[email protected]

SOURCE Eko Health

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

AHA

14 Nov 2024

Code paves the way for reimbursement and expanded clinical use of AI-enabled heart disease detection

SAN FRANCISCO, Nov. 14, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Eko Health, a pioneer in applying artificial intelligence for early detection of heart and lung diseases, today announced the issuance of a Category III Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code by the American Medical Association (AMA) for its SENSORA™ platform. The newly issued Category III CPT code will be effective on July 1, 2025, and is the first step to coverage and reimbursement for SENSORA™, bringing advanced heart disease detection to clinicians across the U.S.

Continue Reading

Code paves the way for reimbursement and expanded clinical use of AI-enabled heart disease detection.

SENSORA is an advanced early disease detection platform that includes FDA-cleared AI algorithms that identify signs of structural heart murmurs, low ejection fraction (Low EF), and arrhythmias, including AFib, in the front-line care setting. It seamlessly integrates with Eko's CORE 500™ digital stethoscope, which embeds advanced ECG technology in a tool that every provider is familiar with.

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for about 1 in every 5 deaths, according to the CDC. Early detection plays a critical role in improving patient outcomes. By empowering primary care providers to identify cardiac issues earlier, SENSORA™ enhances proactive care and reduces the burden of advanced heart disease management.

"The AMA's creation of Category III CPT code for Eko's AI disease detection algorithms is a major step in increasing access to early heart disease detection," said Connor Landgraf, CEO of Eko Health. "This milestone will help enable clinicians to use powerful, validated tools to identify heart disease early, ultimately improving patient outcomes, especially in communities with limited access to specialist care."

SENSORA's AI algorithms, validated in clinical and real-world studies, assist clinicians in detecting cardiac disease signs often missed by standard care. An independent clinical validation published in Circulation showed that Eko's structural heart murmur detection AI doubled sensitivity for structural heart disease compared to an analog stethoscope. Additionally, a Lancet Digital Health study involving over 1,000 patients confirmed Eko's low ejection fraction AI accurately detects reduced ejection fraction in primary care, leading to its deployment in over 100 UK clinics by the NHS and Imperial College London.

The Category III CPT code reflects SENSORA's growing role as an essential tool in cardiac care and is expected to expand its use across multiple clinical environments. This designation is a testament to Eko's commitment to equipping primary care clinicians with AI tools that elevate patient care standards and bridge the preventive care gap.

About Eko Health

Eko Health is a leading digital health company advancing how healthcare professionals detect and monitor heart and lung disease with its portfolio of digital stethoscopes, patient and provider software, and AI-powered analysis. Its FDA-cleared platform, used by over 500,000 healthcare professionals worldwide, allows them to detect earlier and with higher accuracy, diagnose with more confidence, manage treatment effectively, and ultimately give their patients the best care possible. Eko Health is headquartered in Emeryville, California, with over $165 million in funding from ARTIS Ventures, DigiTx Partners, Double Point Ventures, EDBI, Highland Capital Partners, LG Technology Ventures, Mayo Clinic, Morningside Technology Ventures Limited, NTTVC, Questa Capital, and others.

For more information, visit .

Media Contact

Sam Moore

[email protected]

SOURCE Eko Health

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

02 Oct 2024

Patients identified with reduced ejection fraction using Eko Health AI were twice as likely to experience heart attacks, heart failure, hospitalization, and all-cause mortality over two years.

SAN FRANCISCO, Oct. 2, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Eko Health, a pioneer in applying artificial intelligence (AI) for early detection of heart and lung diseases, today announced a new independent study from researchers at Imperial College London (Imperial) that demonstrated how AI can identify patients with significantly higher risk of experiencing major adverse cardiac events (MACE), including heart attacks and heart failure. Researchers used Eko Health's FDA-cleared and UKCA-marked Low Ejection Fraction AI to conduct the study, which reinforced the power of Eko's AI for early detection while also showing its potential to improve cardiovascular care in both clinical and remote settings.

Continue Reading

Patients identified with reduced ejection fraction using Eko Health AI were twice as likely to experience heart attacks, heart failure, hospitalization, and all-cause mortality over two years.

Imperial researchers unveiled three significant studies at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2024, demonstrating:

Eko AI Predictive of Major Adverse Cardiac Events and Mortality

In a pivotal study involving over 1,000 patients, Eko's AI was shown to predict MACE—including heart attacks, heart failure, and hospitalization—as well as all-cause mortality. Patients flagged by the AI for low ejection fraction were twice as likely to experience MACE compared to those without a positive AI result. These patients also faced a 65% higher mortality rate, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors.

"These findings underscore the power of AI-ECG in identifying patients at a significantly higher risk of MACE and mortality, even when traditional markers like left ventricular ejection fraction appear normal. In our study, patients with a positive AI-ECG result had more than double the risk of MACE and a 65% higher risk of mortality. This technology represents a critical advancement in early cardiac risk stratification, offering the potential for more targeted interventions through the simple addition of a single-lead ECG," said Dr. Patrik Bächtiger, one of the co-leads of this research at Imperial.

"Notably, the AI identified at-risk patients who had unremarkable results from traditional diagnostic tools, such as echocardiograms. This highlights the technology's ability to detect hidden risk factors, offering healthcare providers a powerful tool for early intervention and improved patient outcomes," said Prof. Nicholas S. Peters, Director of the Health Impact Lab at Imperial.

Eko AI Expands Remote Care Capabilities for Heart Failure Patients

In another Imperial study presented at ESC 2024, Eko's AI technology demonstrated its potential for remote patient monitoring, particularly for individuals with heart failure. The study found that Eko's AI could accurately predict changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which is a critical indicator of heart function in heart failure patients. By being able to monitor changes in LVEF from home, patients could benefit from earlier interventions and personalized adjustments to their treatment plans, reducing the need for frequent hospital visits and providing peace of mind.

Eko AI Demonstrates Scalability for Widespread Clinical Integration

Over a 12-week period, the Imperial team successfully integrated Eko's AI across 71 primary care sites in the UK. The study highlighted both the consistent and seamless adoption of the technology by healthcare providers, in addition to its ability to enhance patient care without straining existing healthcare systems. "This demonstrates the technology's practicality and scalability for widespread clinical use, paving the way for broader implementation in routine medical practice," said Dr. Mihir Kelshiker, one of the co-leads of this program at Imperial.

Together, these findings further solidify Eko's Low EF AI technology as an important innovation for early detection and management of cardiovascular disease, reinforcing its role as an essential tool in advancing patient care.

"This important research from Imperial College London highlights the transformative potential of Eko's AI technology in the fight against heart disease," said Connor Landgraf, co-founder and CEO of Eko Health. "By identifying patients at elevated risk for major cardiac events with a simple, non-invasive test, we are empowering clinicians worldwide to take action earlier, ultimately saving lives and improving care outcomes on a global scale."

About Eko Health

Eko Health is a leading digital health company advancing how healthcare professionals detect and monitor heart and lung disease with its portfolio of digital stethoscopes, patient and provider software, and AI-powered analysis. Its FDA-cleared platform, used by over 500,000 healthcare professionals worldwide, allows them to detect earlier and with higher accuracy, diagnose with more confidence, manage treatment effectively, and ultimately give their patients the best care possible. Eko Health is headquartered in Emeryville, California, with over $165 million in funding from ARTIS Ventures, DigiTx Partners, Double Point Ventures, EDBI, Highland Capital Partners, LG Technology Ventures, Mayo Clinic, Morningside Technology Ventures Limited, NTTVC, Questa Capital, and others.

Media Contact

Sam Moore

[email protected]

SOURCE Eko Health

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

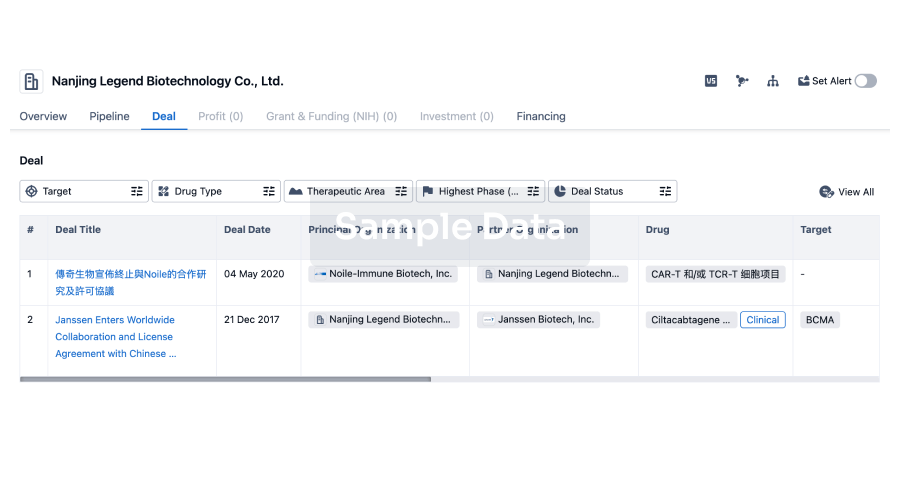

100 Deals associated with Artis

Login to view more data

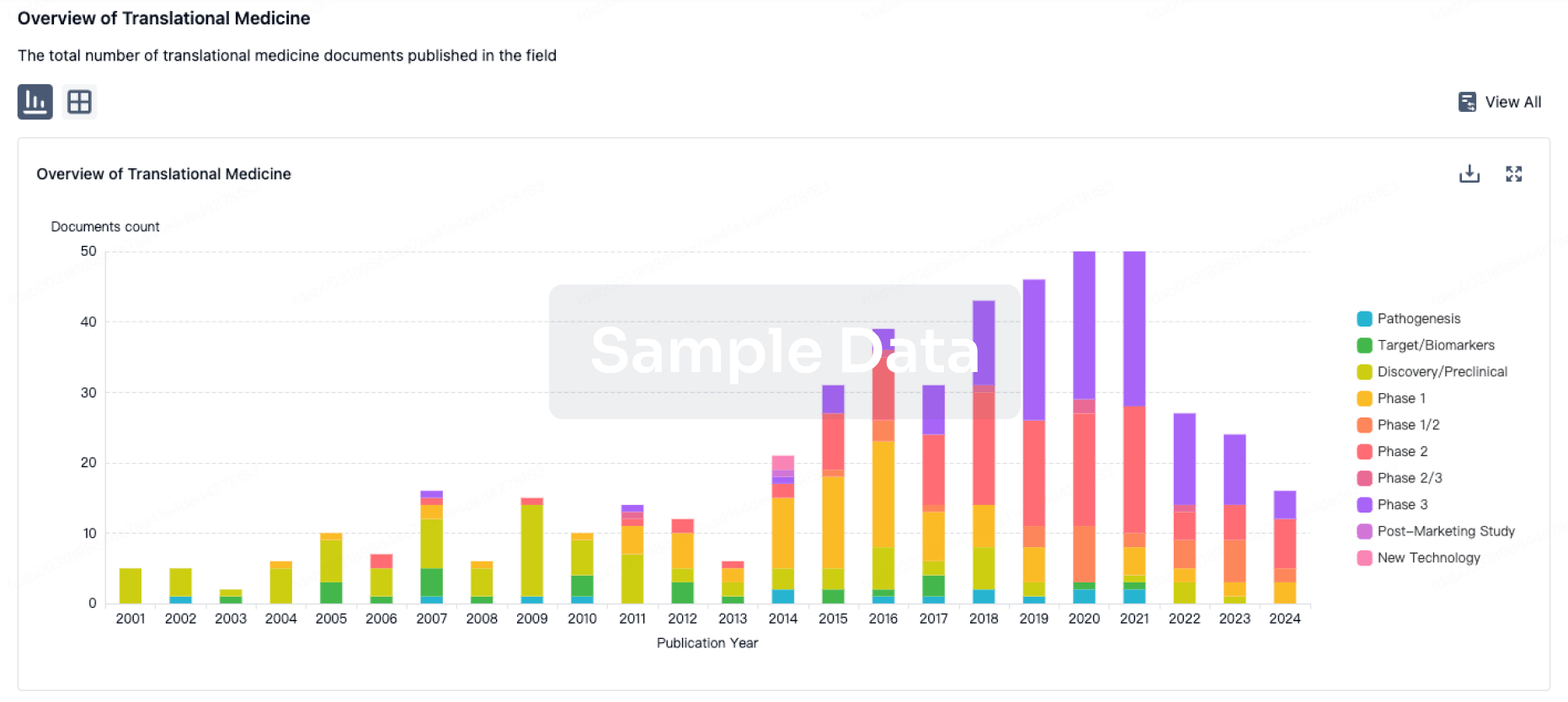

100 Translational Medicine associated with Artis

Login to view more data

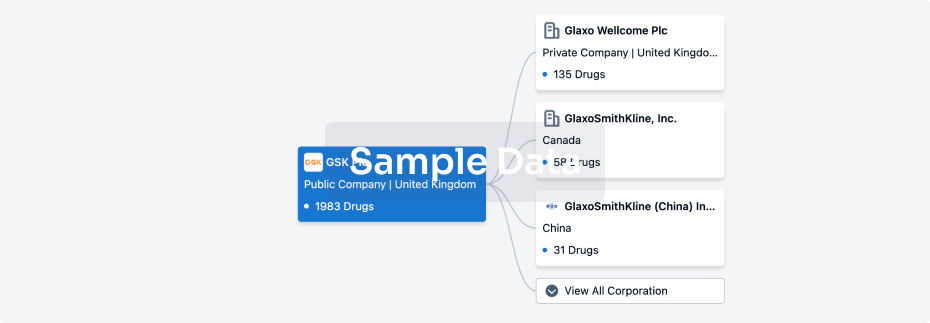

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 20 Dec 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

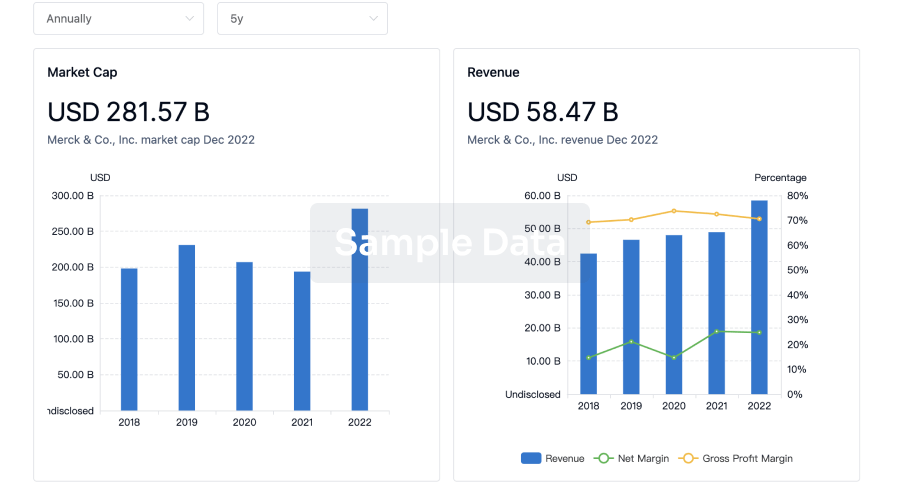

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

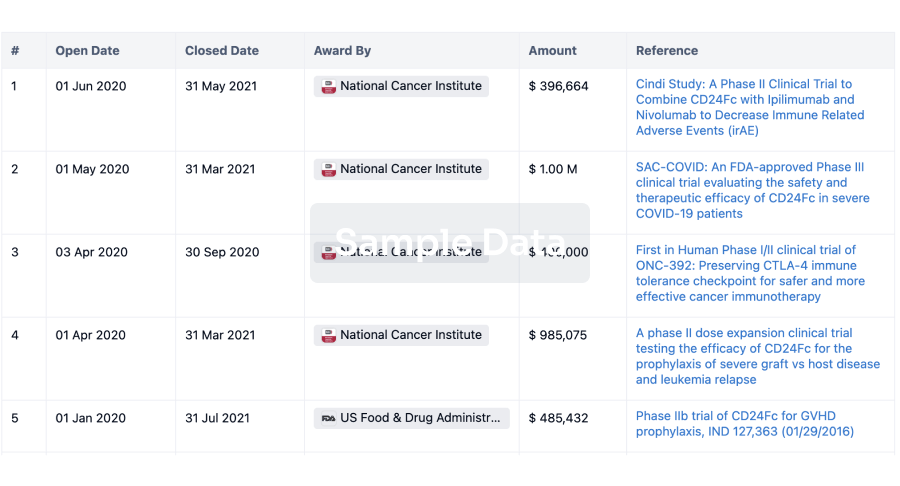

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

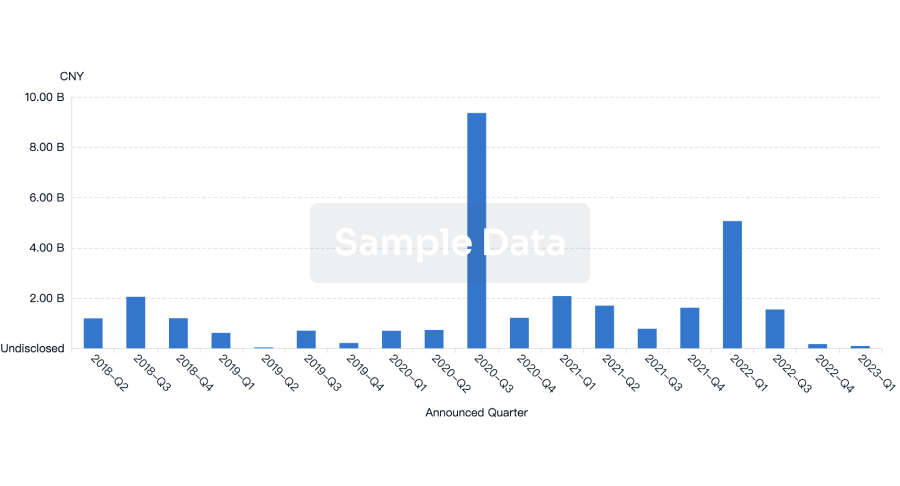

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

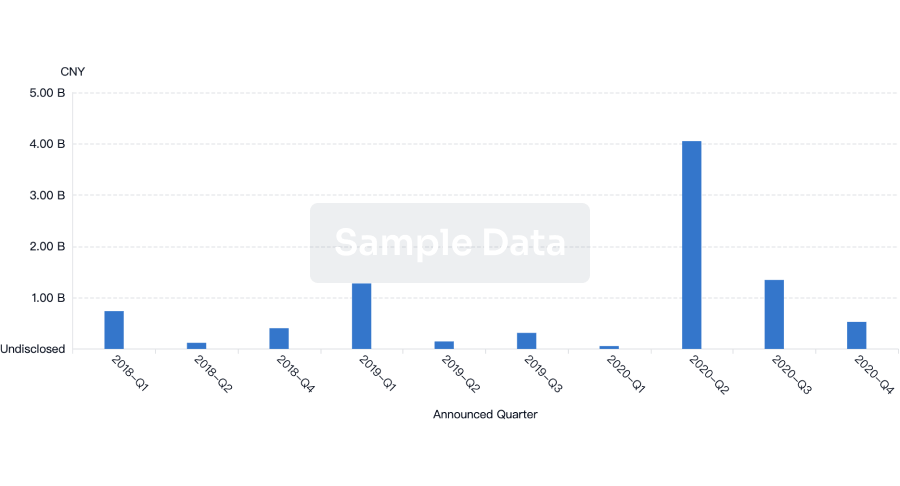

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free