Request Demo

Last update 06 Dec 2025

TE Connectivity Ltd.

Last update 06 Dec 2025

Overview

Related

100 Clinical Results associated with TE Connectivity Ltd.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with TE Connectivity Ltd.

Login to view more data

71

Literatures (Medical) associated with TE Connectivity Ltd.01 Nov 2021·MATERIALS & DESIGN

A holistic X-ray analytical approach to support sensor design and fabrication: Strain and cracking analysis for wafer bonding processes

Author: A. Neels ; A. Borzì ; A. Dommann ; J.F. Le Neal ; S. Dolabella ; P. Drljaca ; G. Fiorucci ; R. Zboray

Devices such as sensors, actuators, or micro-electromech. systems (MEMS) are obtained by a variety of microfabrication processes.Many of these processes influence the material systems by the introduction of strain and defects, which may affect the final device's performance and reliability.Indeed, controlling materials status during the microfabrication is fundamental for the process optimization itself and for guaranteeing the highest devices performances during their lifetime.In this work, a conjoint anal. approach between high-resolution X-ray diffraction (HRXRD) and X-ray micro-computed tomog. (CT) evaluates an innovative silicon-to-sapphire wafer bonding process.Large cracks 30-60μm-thick were identified in both crystals by micro-CT and related to the interfacial high-stress release.In parallel, a multi-domain microstructure associated with strain and tilt affect the silicon crystallinity due to smaller cracks and defects which originate at the bonding interface and travel to the outer part of the crystal.The effectiveness of the bonding is also assessed by our approach and further enforced by means of SEM observation of the sample cross-section.Here, a unique approach by combining X-ray micro CT with HRXRD for a holistic evaluation of silicon-to-sapphire wafer-bonding processes and correlate the micrometer scale and volumetric defect detection (voids and cracks) with at.-level strain and defect anal. is presented.

01 Aug 2020·Additive Manufacturing

In-situ X-ray tomography analysis of the evolution of pores during deformation of a Cu-Sn alloy fabricated by selective laser melting

Author: Bayes, Martin ; Samei, Javad ; Misiolek, Wojciech Z. ; Ventura, Anthony P. ; Wilkinson, David S. ; Pawlikowski, Gregory T. ; Amirmaleki, Maedeh

In-situ uniaxial tensile tests coupled with X-ray computed tomog. (XCT) were carried out on a Cu-4.3Sn alloy fabricated by selective laser melting.XCT models were constructed to enable step-by-step visualization of pore growth during deformation.Evolution of pores (mean diameter, d., volume fraction and sphericity) was quantified as a function of plastic strain.Evolution of the largest 7 pores existing in the as-printed part are individually characterized and coalescence is graphically presented.Results show that macroscopic instability begins once the largest internal pores reach the surface.Also, accelerated growth and coalescence of the largest 50 pores leads to rapid localization of strain followed by fracture.Pore growth was modeled using the Rice-Tracey (RT) and Huang models for different populations of pores and the parameters were optimized.The RT and Huang constants were found to depend on the initial mean pore diameter

01 Apr 2018·MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING A-STRUCTURAL MATERIALS PROPERTIES MICROSTRUCTURE AND PROCESSING

Alleviating surface tensile stress in e-beam treated tool steels by cryogenic treatment

Author: Zhu, Yuntian ; College, David A.

Electron beam (e-beam) treatment of tool steel surfaces has been available for several decades as an approach to create hard surface layers on tool steels.The e-beam process produces ultrafine grain sizes through ultra-rapid cooling of the melt layer, which helps with improving wear resistance to increase the service life of tools.However, its implementation in many applications has been limited by the accompanying residual tensile stresses in the surface layer, which is undesirable and may lead to premature fracture.Here we report the utilization of cryogenic freezing after e-beam treatment to reduce the residual tensile stress.The e-beamed specimen contained high levels of retained austenite in the surface layer.The cryogenic treatment converted the retained austenite into martensite, and the corresponding volume expansion reduced the peak tensile residual stress by 28%, which makes it a promising method to expand the applications of e-beamed tool steel.

42

News (Medical) associated with TE Connectivity Ltd.15 Sep 2025

There is an indisputable trend toward minimally invasive, outpatient procedures in healthcare. Outpatient procedures help to alleviate burdens on the healthcare system, save patients time, money, and decrease procedural risks.

Minimally invasive sensors for heart arrhythmia are transforming cardiac medicine, supporting a shift to outpatient care. Heart arrhythmia sensors are

becoming

increasingly smaller, more specialized, more advanced, and more widespread, leading to shorter recovery times, reduced risks, and better patient outcomes.

Mike Klitzke, Senior Principal System Architect at TE Connectivity and a

speaker

at MD&M Midwest in October, spoke with

MD+DI

about PFA, RF ablation, and the revolution of catheter sensors.

How have minimally invasive approaches revolutionized the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias compared to traditional open procedures?

Klitzke:

When we look at open procedures, where you actually have to open the heart, in a lot of those cases, to get to the area to perform a procedure, you have to do a bypass and in some cases you have to stop the heart. All of these specific processes can be very traumatic to the patient in terms of physical trauma. It'll take a significant amount of time to recover, and there's more significant risks. Infection, bleeding, and in terms of bleeding there's a risk of clotting, which can cause things like embolism and so forth. There is a set of additional risks associated with that. When we go to a minimally invasive procedure, which uses a much smaller incision and does not open up the cavity, the risk of infection and bleeding is significantly reduced. Furthermore, because of the small size, there is a reduction of time as well. The time of the procedure is greatly reduced. If you look at the time of the procedure and time of recovery, you may go from a procedure where a patient is in the hospital for a few days, to an outpatient procedure.

Not only that, but you can look at it from a couple of different ways. One being, how many procedures you can do in a given time period, because a patient is occupying space in a hospital. If you can go to an outpatient procedure, you can service more hospital patients, adding greater accessibility in terms of being able to provide treatment to patients. Another thing in terms of accessibility that is important, is a lot of times these things develop in older patients and they cannot recover from an open heart surgery. There is more significant risk and recovery for older patients. Sometimes a doctor may indicate that you are not a good candidate for such an invasive procedure. With minimally invasive procedures, you can offer care to a broader range of patients that may not have access. One thing I would highlight in medicine in general is, goals are always going to be improved patient safety and improved outcomes. When we look at that from a minimally invasive procedure, those are two of the best outcomes. When talking about bleeding, infections, etc. are being reduced, and the improved outcomes are that the patient is healthy and doing well after a given period of time. You really see that with minimally invasive procedures, and you see an increase in patient outcomes.

How has sensor technology specifically improved the safety profile of RF ablation procedures?

Klitzke:

When we look at RF ablation, there are a few things about it. What it does is the RF frequency is coupling to the dipole movement of water. So that means anything with water is going to get heated up with the exposure to the RF. If we look at sensors, the first sensors ever implemented in RF ablation were temperature sensors. The things it really did is, you put it at the point of ablation, so the idea is if you monitored the temperature at that point, you could make sure of a few things. One is that you have a consistent process. So the doctors realize we want to hit a given range, because if you get variation in temperature, you will get variation in the procedure, which creates variation in the patient outcomes. So you want to have consistency in the procedure, and a temperature sensor is a key way to do that. What they also do is, those temperature sensors really guarantee patient safety. You want to make sure you are not exceeding certain temperatures. One of the things that can happen, if you are having so much temperature invade into the heart, that can lead to blood bubble formation and subsequent complications. What you'll see in some catheters is multiple temperature sensors. Some at the electrodes and some away from the electrodes, so you know what is happening away from that point. Because obviously, you want to keep a certain temperature at the heart, like the tissue you are ablating, but you also want to make sure you are not exceeding certain temperatures in the bloodstream of the heart. Some catheters will implement multiple temperature sensors.

So those were the first sensors that were integrated into RF ablation catheters, but as more procedures occurred, people were looking for different methods to make procedures more consistent and increase patient safety. Around 2010, you started seeing studies that looked at if forced sensing could benefit the procedure. In the 2013 and 2014 time frame, you saw the first devices come out with force sensing. What they found out with studies prior to that was that energy that was coupled to the heart was not just a function of temperature, but also a function of force. To have the consistency in the amount of energy delivered to the heart, you needed to measure both force and temperature. You would see that in the outcomes of these studies, you would see an improvement with the actual patient outcome. You had more likelihood of success if you were monitoring both the force and temperature. Coming back to patient safety, what can happen if you have too much energy, (a function of both force and temperature) one of the things that can happen is you may cause the blood inside a heart cell to boil. There's a phenomenon called steam popping, where basically liquid is boiling, it pops a cell and you get more damage than you are intending. You want to create a lesion, which means you want to stop electrical activity which is causing arrhythmia, but you do not want to cause structural damage, and steam pops can result in perforation of the heart tissue. At which point, you have to switch to an open procedure to repair. You really want to monitor the process to avoid potential complications. It is a combination of having that patient safety, not exceeding certain temperatures, both in the heart wall but also in the blood surrounding the heart, and making sure it's consistent. If it is consistent, surgeons will know for this much energy, for this much time, I will get a liaison of this size. There will always be variation from patient to patient, but it gives them a better view, and that consistency helps ensure that they are treating the arrhythmia and there is not going to be a recurrence.

What are the most significant recent advancements in force-sensing technology for cardiac ablation catheters?

Klitzke:

When we look at that, just the sensing itself, incorporating force sensing, was one of the most significant advancements. If you look at the market today, there are various methods of incorporating sensors. Some sensing is based on fiber optics, there are also magnetic methods and strain sensors. All of these methods are used in RF ablation catheters today. Really, where advancements come in is how to make them small enough to integrate into the catheter, and how to get the accuracy and performance needed. With RF ablation, it is not only important to measure force along the axis of the catheter, but sometimes the catheter is not at a perpendicular angle to the heart wall. It may hit it at a variety of angles. So it’s very important to not measure the force along the axis, but to measure force off axis as well. If you look at it you really want to know the vector force that is being applied to the heart. When we start looking at advances, it is about improving accuracy, getting that extra sensitivity off axis, and one of the key things with implementing this technology into the catheters is, lots of other things have to happen in the catheters. You have to have electrical lines running to the electrodes, which convey the RF frequency, many catheters have irrigation functions, which helps them control the temperature. Now you can think, you are applying RF energy and monitoring heat with a temperature sensor, but irrigation allows control and taking energy in and out with irrigation. With all the additional features, it's important that sensors be small enough that you can incorporate all of this. Everything has to be incorporated into that smaller catheter. You really see where developments are occurring, because it is around how to implement more sensors and how to integrate them. How do you integrate into the catheter, and how do you manage it into the assembly of the catheter. There’s a lot of things that are happening within that catheter.

How has cardiac mapping technology evolved to provide more accurate identification of arrhythmia sources?

Klitzke:

What has really changed with mapping is the number of electrodes. When we say mapping, we are trying to understand electrical mapping along the heartwall to determine where there is arrhythmia. We measure that signal with electrodes in a cardiac mapping catheter. So what you are seeing in the last few years is more and more electrodes. There are a couple of reasons for this. One reason is when you're doing mapping, it allows you to map the procedure quicker. You are able to reduce the procedure time by having an array of electrodes versus just a couple of signal electrodes. You can map a larger portion of the heart at a given time. The other thing is, what you want to do is ensure you are getting an accurate reading. To ensure you have an accurate reading, you have to know the electrode is in contact with the heart wall. If you don’t have contact, you can get a false reading and you can totally miss the arrhythmia. One thing that is done is looking at the impedance across multiple electrodes, and looking at the signal quality across multiple electrodes. And that gives confidence on whether or not it's a good measurement. A lot of companies will develop advanced algorithms to specifically coordinate all of these data points that they have from the multiple electrodes to ensure they are getting accurate data. The outcome of moving toward these arrays is faster procedures and more reliable data. With that, you get improved patient outcomes because with better data and better idea where arrhythmia is occurring, that allows the surgeon to pinpoint that area, to ablate that area, with the end goal of not having recurrence of the arrhythmia.

If we look at how that's evolving, even with that technology of switching to arrays, we still find in clinical studies that there's a risk you are not getting an accurate measurement. Maybe you have a signal, but you don’t have good contact, so you are getting some type of false reading. So what they are often looking at is, how can we do additional backup with contact sensors to verify the electrodes are in contact? So this sensor in many cases is not going to be the electrical signal. You are actually looking at a contact force or some other method of measuring contact. What's different here, from RF ablation, RF is you need to know the magnitude of the force. So you really want to be going to a set force and you want to know the magnitude of the force. For mapping, what you want to know is whether or not you have good contact. It is really a different goal of what you are trying to do. With RF, you are trying to understand angles. Not only magnitude, but how the electrode is interfacing with the heart. With mapping, it is about saying, do I have good contact? As we see this evolving, what we are starting to see is ablation catheters being combined with mapping catheters. The benefit of these combined catheters is it simplifies the procedure. Now, instead of having to go in, map, and remove the mapping catheter, it’s a single catheter that goes in. It’s a simplified procedure, it takes less time, and it facilitates once it's mapped I can ablate and, since I still have the catheter there, I can go in and take another mapping and see if the arrhythmia is actually gone. I can get verification of a successful procedure. There are still risks, but it's a big improvement from where procedures used to be. There's other benefits to being under less time, less time under anesthesia, there are benefits to the patient and to the healthcare system because if I can do things quicker, that provides additional accessibility.

How might emerging technologies like pulsed field ablation change the sensor requirements for these procedures?

Klitzke:

What we saw in 2024 was catheters coming out that had both pulsed field ablation, RF ablation, and mapping in a single catheter. The reason why that happened, if we look at PFA it's fairly new. The first approved catheters came out in 2024 that were approved by FDA. While there have been clinical studies, the amount of data available is not as significant as with RF, which has been around since prior to the 90s. There's a lot more data there. Some surgeons want to have confidence that they will be successful in treating patients. Some surgeons still think PFA is new, and while they do see potential benefits, they think because it's so new, we may not understand all of the potential risks. So these catheters provide surgeons with options. They can do pulse, they can do RF, and they can do mapping. Again, we are seeing trends of combining functionality and catheters. When we talk about PFA being new, the initial benefit is, it’s non-thermal, or significantly less thermal at least, there are studies that indicate there is some thermal aspect but it's much less. The other thing is it is selective in the tissues. It seems to have a greater effect on muscle tissue versus other tissues. The benefit there is, the esophagus is right behind the heart, and studies show that there can be thermal damage to the esophagus with RF ablation. That impacts recovery time, and is one of the great complications of RF. With PFA, there is less risk to the esophagus. That's a big benefit driving PFA as it is less thermal and appears to be selective in the tissues it ablates. And another thing is it looks like the data indicates that it is not a function of force, like where we need to know the magnitude of the force. So when we start saying how is PFA going to change sensor requirements, one key thing is if it is non-thermal, the criteria for thermal sensors may change. There still may be a need for them, but some of the first PFA catheters don't have temperature sensors, but some that came out in the past year do. That's kind of still evolving, and because it is less thermal, maybe the importance of having them is not the same. We can see a change in temperature sensor requirements. Maybe you don’t need as many or the same accuracy. That may change, as well as those requirements there.

PFA is not a function of force in terms of magnitude, so you don’t need the same type of sensor that you would need in RF ablation where you are trying to have a consistent given magnitude of force. That being said, studies in the last year show there are still risks with PFA. Some of them can be microbubble formations in the blood, and with that risk factor, some studies may indicate that you get less risk if you can guarantee contact of the PFA sensor with the tissue. What it seems like to get optimal patient outcomes and optimal procedures, you want to know that the catheter is in contact. Like with a mapping catheter, the prioritization is you want to be in contact. You don’t need to know the magnitude of the force, but you need to be in contact. We also see with arrays they are in different geometries. Some catheters will have spherical geometries, and some have other geometries. With that, that in itself and the geometries of these catheters, is a new requirement on these contact sensors. The method of doing the contact sensing has to be compatible with these new geometries. You are seeing that in terms of a change in the requirements from RF ablation, where you need to know on access I am having one force sensor because I am having one point of ablation, but now I am seeing an array of points and I am not measuring the magnitude of the force, but I need to measure contact. Those are very different requirements, so solutions end up being different. Maybe I need 10 force sensors, or 11, instead of one. With that, it's not only about geometry, accuracy, and other factors that go into it, it's now, let's take temperature for example. Temperature sensors typically have two leads that you have to run through the catheter. Now I have four leads running through the catheter, or if I go to 10 or 20 leads, I have to manage them through the catheter. So how to manage those signals becomes more challenging. Now I have 10 temperature sensors and 10 contact sensors. Now, who knows, maybe I have 40, 60 leads that I have to manage through that. When we start seeing these new requirements, it’s not just about functionality and accuracy, but it's also about form and challenge to integrate that many sensors and it is a different scope of problem than with older technologies. When we start looking at how sensors are going to evolve, that will be a big thing. Part of it is integration, how to deal with complex geometries, it is definitely a new challenge. One of the other big challenges as we move forward is PFA is happening at higher voltages than were used previously. In general, we are still seeing some variation. There may be other factors that drive optimization, but those high voltages themselves will drive new requirements.

Now, sensors have to operate at these higher voltages. High voltages potentially can impact other factors. A lot of different factors have to be accounted for. There are different types of technology, and multiple technologies you can do contact sensing with. Each one will have tradeoffs. In many cases, you really have to look at the given design and the given operation of that specific catheter to optimize selection of sensors. One set may be great for this given design, but it may not be the case for others. It's about understanding those designs, the operation, that is really going to drive those requirements and in turn it will drive evolution. Going forward, the medical community will learn new things, the medical device companies will, and so will we. All of these companies need to work together to find solutions that improve outcomes and improve patient safety.

Is there anything else you would like to expand on?

Klitzke:

I want to reiterate what I was just saying; there’s lots of different types of technologies. At TE today, we have sensors for minimally invasive procedures including pressure, temperature force, ultrasonics, and we are always continuing to look at and develop new sensors. Another key one we were looking at is magnetic. It's about selecting the right technology for the given application and understanding that. Many times, there are multiple ways to measure a given parameter, and a lot of times that is a discussion that we need to have with the medical device companies to make sure we are giving them the best options for achieving their goals.

02 Oct 2024

Eli Lilly’s R&D has yielded innovations such as the metabolic disorder drugs Mounjaro and Zepbound, both discovered in the company’s labs. Lilly is now committing $4.5 billion for in-house innovations in the manufacturing of medicines.

The pharmaceutical giant on Tuesday announced plans for a new facility, Lilly Medicine Foundry, which it says will research new ways of producing medicines. The site will also enable the company to scale up the manufacturing of experimental drugs for clinical trials. The Medicine Foundry will be constructed in the LEAP Innovation District in Lebanon, Indiana, which is northwest of Indianapolis where Lilly is headquartered. The company expects this new manufacturing site will open in 2027.

Manufacturing has become a major area of investment for Lilly as demand continues to soar for its new metabolic disorder drugs. The company reported $20 billion in revenue for the first half of this year, a 31% increase compared to the same period in 2023. Lilly attributed much of that revenue growth to rising sales of diabetes drug Mounjaro and obesity drug Zepbound. Both are peptides that are expensive to produce. Lilly has been pouring billions of dollars into the expansion of existing facilities and the construction of new sites for manufacturing both medicines in Europe and the U.S.

Sponsored Post

What Healthcare Can Learn from Costco

The path forward is clear: employers must evaluate their health plan the same way they do their Saturday shopping excursion.

By Jeff Bak, Imagine360 CEO and President

The Medicine Foundry’s research will not be limited to peptide drugs. Lilly says this facility will have a flexible design that enables production of various types of medicines, including small molecules, biologics, and nucleic acid therapies. The site will support manufacturing of experimental medicines for clinical trials, Lilly said. Furthermore, new technologies developed at the Medicine Foundry will be transferred to the company’s other sites when drugs are ready for full-scale production.

Locating the Medicine Foundry at LEAP brings another Lilly facility to the district, a 9,000 acre innovation hub about 30 miles northwest of Indianapolis that is becoming a home to corporate campuses, advanced manufacturing, and R&D operations across a range of industries. Lilly has about 600 acres at LEAP. Last year, the pharma giant broke ground for a manufacturing facility that will make the ingredients for drugs, such as its genetic medicines. This past May, the company announced a $5.3 billion expansion of its plans at the LEAP site, adding the capacity to make the main pharmaceutical ingredient in both Mounjaro and Zepbound.

Lilly said Indiana is providing infrastructure improvements for roads, water, and utilities. The state is also offering the company economic incentives tied to investment and employment goals at the Medicine Foundry, which is expected to bring 400 full-time jobs to Lebanon.

“As we accelerate our work to discover new medicines for the toughest diseases, we’re continuing to invest in state-of-the-art infrastructure to support our growing pipeline,” Lilly CEO David Ricks said in a prepared statement. “In addition to supplying high-quality medicine for our clinical studies, this new complex will further strengthen our process development and scale up our manufacturing capabilities to speed delivery of next-generation medicines to patients around the world.”

presented by

Sponsored Post

The Promise of Value-Based Care and MedTech Innovation

Monica Vajani, Executive Director for mHUB’s MedTech Accelerator, discusses how mHUB is helping innovators transition healthcare towards value-based care.

By Monica Vajani - mHUB

Illustration: Eli Lilly

24 Jan 2024

By End-USer, Hospital segment will be significant

NEW YORK, Jan. 23, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- The

disposable endoscope market is to grow by

USD 1.52 billion from 2023 to 2027 progressing at a

CAGR of 15.9% during the forecast period. The report offers an up-to-date analysis regarding the current global scenario, the latest trends and drivers, and the overall environment.

The rising early detection of gastrointestinal diseases is the key factor driving the growth. The widespread adoption of disposable endoscopes in gastrointestinal procedures is positively driven by factors such as the rising demand for minimally invasive techniques, the reduction in nosocomial infections, and the increasing prevalence of gastrointestinal diseases, including colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Continue Reading

Technavio has announced its latest market research report titled Global Disposable Endoscope Market 2023-2027

More details on Market size and coverage with Historic and forecast opportunities (2017 to 2027). Download a Free Sample Report in minutes!

The increasing regulatory approvals from health authorities around the world

is a major trend. The increase in medical waste

is a major challenge to the growth.

The disposable endoscope market analysis includes end-users (hospitals and clinics), applications (bronchoscopy, urologic endoscopy, GI endoscopy, ent endoscopy, and others), and geography (North America, Europe, Asia, and the Rest of the World (ROW)).

The growth of the

hospitals segment will be significant during the forecast period. Hospitals, as healthcare establishments, receive a large number of patients daily. Therefore, they possess advanced facilities and integrated operating rooms to meet the increasing requirements of both physicians and patients. Equipped with sophisticated infrastructure, hospitals can effectively diagnose and monitor the treatment of various diseases and conditions.

The sample report provides information on market dynamics and gives data for Market Opportunity Transformation Growth & Capitalization

The disposable endoscope market covers the following areas:

Disposable Endoscope Market Sizing

Disposable Endoscope Market Forecast

Disposable Endoscope Market Analysis

Companies Mentioned

Acteon Group Ltd.

Ambu AS

Boston Scientific Corp.

Coloplast Corp.

Endoso Life

Flexicare Group Ltd.

Hill Rom Holdings Inc.

KARL STORZ SE and Co. KG

Medtronic Plc

Olympus Corp.

Parburch Medical Developments Ltd.

STERIS Plc

SunMed

TE Connectivity Ltd.

The Cooper Companies Inc.

Timesco Healthcare Ltd.

Acteon Group Ltd. - The company offers disposable endoscope for ENT areas. Also, the company offers foundations, moorings, marine electronics and instrumentation, flow lines, offshore risers, conductors for shallow, and deepwater applications.

Technavio's SUBSCRIPTION platform

Disposable endoscopes: Major Applications

Disposable endoscopes, a type of endoscopy device and medical device, find applications in minimally invasive surgery, utilizing flexible endoscopes for diagnostic imaging in procedures like gastrointestinal endoscopy and laparoscopic procedures. These single-use endoscopes play a role in healthcare technology, aiding in surgical instruments and infection control as medical disposables. They are used in various endoscopic procedures and visualization systems, contributing to the trends of disposable endoscopes and endoscope innovation. The disposable endoscope market caters to the demand for sterile endoscopy, with a focus on endoscope manufacturing and disposable camera endoscopes. This medical imaging tool is also utilized in interventional endoscopy and ambulatory surgery.

Related Reports

The

global endoscopy devices market size is estimated to grow by USD 14,039.24 million at a CAGR of 7.36% between 2022 and 2027.

The

global laparoscopic devices market size is estimated to grow by USD 4,396.16 million at a CAGR of 8.11% between 2022 and 2027.

ToC:

Executive Summary

Market Landscape

Market Sizing

Historic Sizes

Five Forces Analysis

Segmentation by Application

Segmentation by End-user

Segmentation by Geography

Customer Landscape

Geographic Landscape

Drivers, Challenges, & Trends

Company Landscape

Company Analysis

Appendix

About US

Technavio is a leading global technology research and advisory company. Their research and analysis focus on emerging trends and provide actionable insights to help businesses identify opportunities and develop effective strategies to optimize their positions. With over 500 specialized analysts, Technavio's report library consists of more than 17,000 reports and counting, covering 800 technologies, spanning across 50 countries. Their client base consists of enterprises of all sizes, including more than 100 Fortune 500 companies. This growing client base relies on Technavio's comprehensive coverage, extensive research, and actionable insights to identify opportunities in existing and potential areas and assess their competitive positions within changing scenarios.

Contact

Technavio Research

Jesse Maida

Media & Marketing Executive

US: +1 844 364 1100

UK: +44 203 893 3200

Email: [email protected]

Website:

SOURCE Technavio

100 Deals associated with TE Connectivity Ltd.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with TE Connectivity Ltd.

Login to view more data

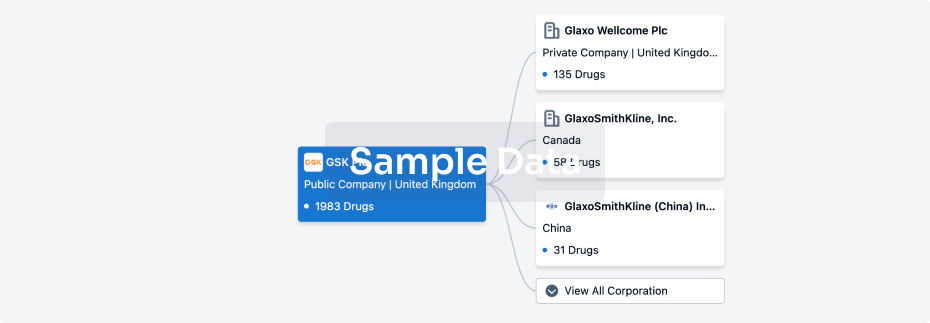

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 19 Dec 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

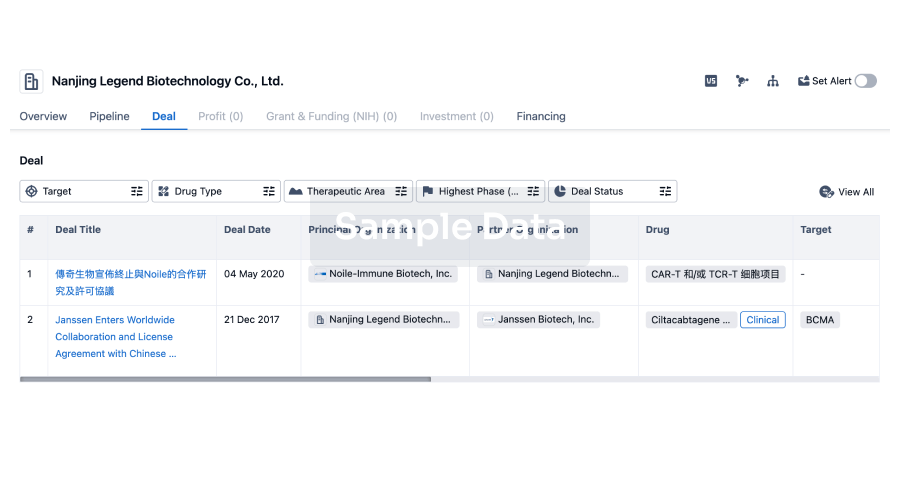

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

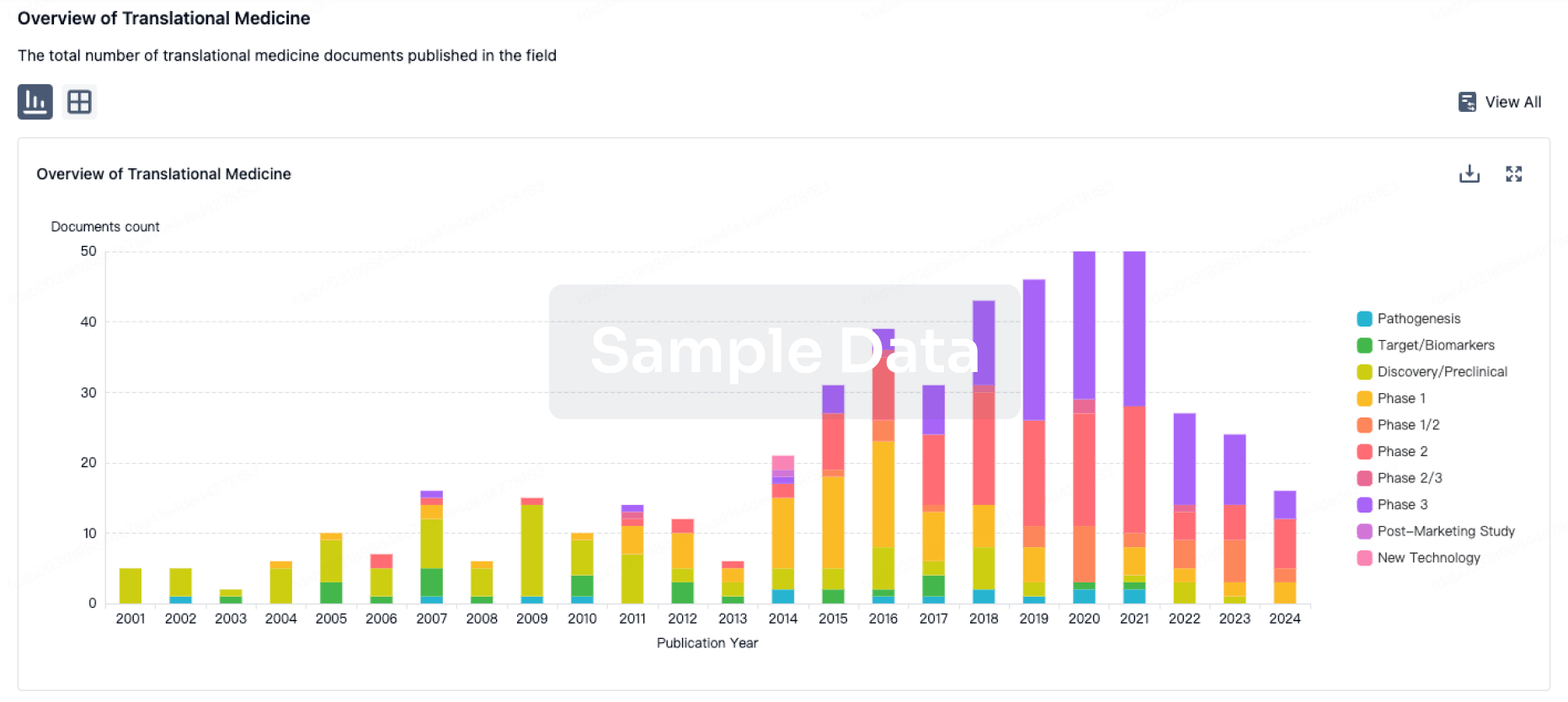

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

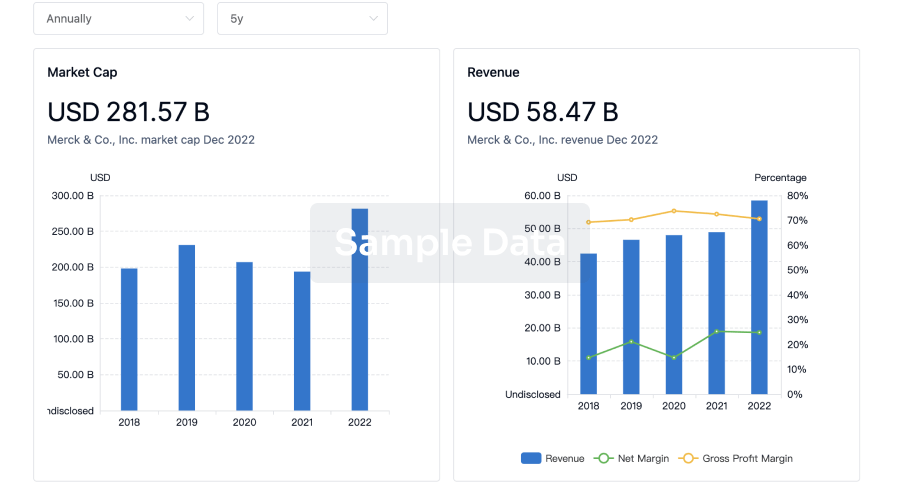

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

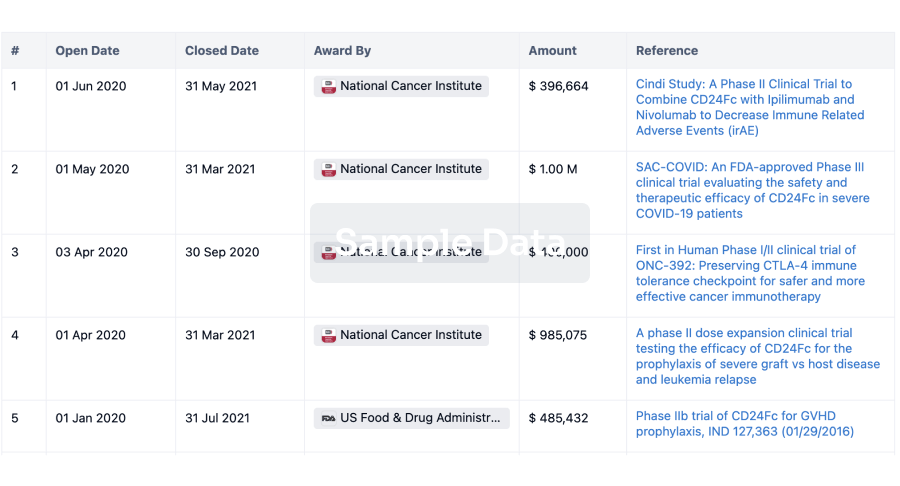

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

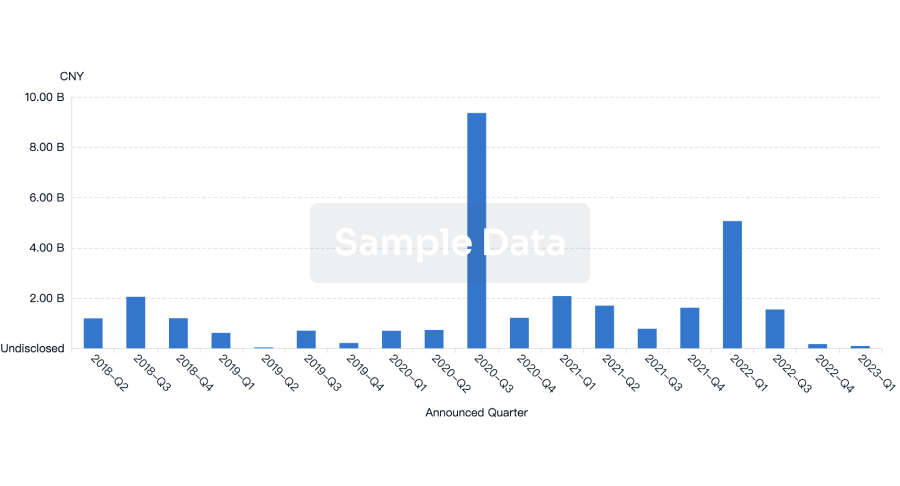

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

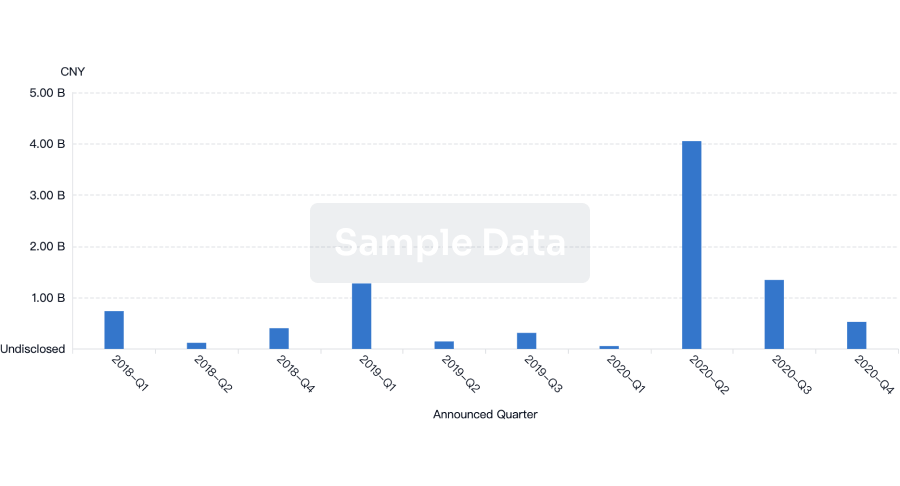

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free