Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

AMYR

Last update 08 May 2025

Basic Info

Synonyms- |

Introduction- |

Related

44

Drugs associated with AMYRTarget |

Mechanism AMYR agonists [+2] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date20 Jan 1800 |

Target |

Mechanism AMYR agonists [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date20 Jan 1800 |

Target |

Mechanism AMYR agonists [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date20 Jan 1800 |

110

Clinical Trials associated with AMYRNCT06926842

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 2 Trial of Once-Weekly Petrelintide Compared With Placebo in Participants With Overweight or Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes

The main purpose of this study is to investigate efficacy and safety of three doses of petrelintide versus placebo in participants with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Start Date21 Apr 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator  Zealand Pharma A/S Zealand Pharma A/S [+1] |

NCT06916065

A Phase 1, Open-Label, Single and Multiple Dose Study to Investigate the Safety, Tolerability, and Relative Bioavailability of Single and Multiple Weekly Subcutaneous Doses of Eloralintide, and Single and Multiple Weekly Subcutaneous Doses of Eloralintide With Tirzepatide in Participants With Overweight or Obesity

The purpose of this study is to evaluate how well eloralintide and eloralintide with tirzepatide is tolerated and what side effects may occur in participants with overweight or obesity. The study drug will be administered subcutaneously (SC) (under the skin). Blood tests will be performed to check how much eloralintide and eloralintide with tirzepatide get into the bloodstream and how long it takes the body to eliminate it.

There will be 6 cohorts. The study will last up to approximately 26 weeks, excluding screening for Cohorts A and B, 11 weeks for Cohorts C and D, and 12 weeks for Cohorts E and F.

There will be 6 cohorts. The study will last up to approximately 26 weeks, excluding screening for Cohorts A and B, 11 weeks for Cohorts C and D, and 12 weeks for Cohorts E and F.

Start Date01 Apr 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06916091

A Phase 1, Investigator- and Participant-Blinded, Placebo Controlled, Randomized, Single Dose Study to Investigate the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Eloralintide (LY3841136) in Chinese Participants With Obesity or Overweight

The purpose of this study is to evaluate how well Eloralintide (LY3841136) is tolerated and what side effects may occur in overweight and obese Chinese participants. The study drug will be administered subcutaneously (SC) (under the skin). Blood tests will be performed to check how much Eloralintide gets into the bloodstream and how long it takes the body to eliminate it.

The study will last approximately 10 weeks excluding a screening period.

The study will last approximately 10 weeks excluding a screening period.

Start Date01 Apr 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with AMYR

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with AMYR

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with AMYR

Login to view more data

254

Literatures (Medical) associated with AMYR01 May 2025·Peptides

Multifunctional incretin peptides in therapies for type 2 diabetes, obesity and associated co-morbidities

Review

Author: Flatt, Peter R ; Conlon, J Michael ; Bailey, Clifford J

01 Mar 2025·British Journal of Pharmacology

Synergistic‐like decreases in alcohol intake following combined pharmacotherapy with GLP‐1 and amylin in male rats

Article

Author: Caffrey, Antonia ; Aranäs, Cajsa ; Jerlhag, Elisabet ; Schmidt, Heath D. ; Vestlund, Jesper ; Edvardsson, Christian E.

01 Mar 2025·iScience

From the pancreas to the amygdala: New brain area critical for ingestive and motivated behavior control exerted by amylin

Article

Author: Byun, Suyeun ; Maric, Ivana ; Sotzen, Morgan R ; Börchers, Stina ; Skibicka, Karolina P ; Olekanma, Doris ; Hayes, Matthew R

38

News (Medical) associated with AMYR24 Apr 2025

COPENHAGEN, Denmark I April 24, 2025

I Zealand Pharma A/S (Nasdaq: ZEAL) (CVR-no. 20045078), a biotechnology company focused on the discovery and development of innovative peptide-based medicines, today announced that the first participant has been enrolled in ZUPREME-2, a Phase 2b trial in people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes comparing once-weekly subcutaneously administered petrelintide, a long-acting amylin analog, versus placebo with regards to efficacy and safety

1

.

“We are excited to announce the initiation of ZUPREME-2, the second Phase 2 trial initiated with petrelintide and an important part of our clinical development plan for establishing petrelintide as a best-in-class alternative to incretin-based therapies and a future foundational therapy for weight management”,

said David Kendall, MD, Chief Medical Officer at Zealand Pharma. “

Amylin agonism has shown great potential to provide clinically meaningful weight loss and may also provide additional improvements in glycemic control in people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, and we look forward to evaluating the efficacy and safety of petrelintide as a weight loss therapy in this population.”

About ZUPREME-2

ZUPREME-2 is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter, Phase 2b clinical trial (NCT06926842). The trial will compare three doses of once-weekly petrelintide with placebo, when added to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity in participants with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes.

The trial includes a screening period, a dose escalation treatment period up to 16 weeks with dose escalation every fourth week followed by a maintenance treatment period until week 28, and a follow-up period after treatment is completed until week 38. ZUPREME-2 is expected to enroll a total of approximately 200 participants.

The primary endpoint in the trial is the percentage change in body weight from baseline to week 28. Secondary endpoints include, but are not limited to, body weight loss of ≥5% and ≥10%, absolute change in body weight, change in waist circumference, change in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), change in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), change in fasting glucose, and change in fasting lipids.

For more information about the ZUPREME-2 clinical trial of petrelintide, please visit

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06926842

.

About petrelintide

Petrelintide is a long-acting amylin analog suitable for once-weekly subcutaneous administration that has been designed with chemical and physical stability with no fibrillation around neutral pH, allowing for co-formulation and co-administration with other peptides

2

. Amylin is produced in the pancreatic beta cells and co-secreted with insulin in response to ingested nutrients. Amylin receptor activation has been shown to reduce body weight by restoring sensitivity to the satiety hormone leptin

3,4

, inducing a sense of feeling full faster. Current clinical data or pre-clinical data suggest a potential of petrelintide to deliver weight loss comparable to GLP-1 receptor agonists but with improved tolerability for a better patient experience and high-quality weight loss.

In November 2024, Zealand Pharma presented detailed results from the Phase 1b 16-week multiple ascending dose (MAD) trial at the Obesity Society Annual Meeting (ObesityWeek) 2024. For the presentation, please visit

Scientific publications – Pipeline – Zealand Pharma

.

Petrelintide is also being evaluated in ZUPREME-1, a Phase 2 trial in participants with overweight or obesity (NCT06662539), evaluating five target doses of petrelintide up to 9 mg over 42 weeks of treatment. Enrollment and randomization in ZUPREME-1 was

completed

in three months.

In March 2025, Zealand Pharma and Roche entered a

collaboration and license agreement

to co-develop and co-commercialize petrelintide as a future foundational therapy for people with overweight and obesity. The closing of the transaction is subject to regulatory approvals and other customary closing conditions. The parties expect that the agreement will close in the second quarter of 2025.

About Zealand Pharma

Zealand Pharma A/S (Nasdaq: ZEAL) is a biotechnology company focused on the discovery and development of peptide-based medicines. More than 10 drug candidates invented by Zealand Pharma have advanced into clinical development, of which two have reached the market and three candidates are in late-stage development. The company has development partnerships with a number of pharma companies as well as commercial partnerships for its marketed products.

Zealand Pharma was founded in 1998 and is headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark, with a presence in the U.S. For more information about Zealand Pharma’s business and activities, please visit

www.zealandpharma.com

.

Sources

1. ClinicalTrials.gov. Efficacy and Safety of Petrelintide in Participants With Overweight or Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes (ZUPREME 2). Available at

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06926842

. Last accessed April 2025.

2. Eriksson et al. Presentation at ObesityWeek, November 1–4, 2022, San Diego, CA. Link:

https://www.zealandpharma.com/media/0gnfxg4b/zp8396-sema-coformulation-obesityweek-2022.pdf

.

3. Mathiesen et al. Eur J Endocrinol 2022;186(6):R93–R111.

4. Roth et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(20):7257–7262.

SOURCE:

Zealand Pharma

Phase 2Phase 1License out/inClinical Result

24 Mar 2025

Zealand Pharma announces completion of enrollment in the Phase 2b ZUPREME-1 trial of petrelintide in people with overweight or obesity

Initiated in December 2024, the Phase 2b ZUPREME-1 trial is designed to evaluate five target doses of petrelintide up to 9 mg over 42 weeks of treatment.

Zealand Pharma remains on track to initiate the Phase 2b ZUPREME-2 trial of petrelintide in people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes in the first half of 2025.

March 17, 2025 - Zealand Pharma A/S (Nasdaq: ZEAL) (CVR-no. 20045078), a biotechnology company focused on the discovery and development of innovative peptide-based medicines, today announced that the last participant has been enrolled and randomized to active treatment or placebo in ZUPREME-1, a global Phase 2b trial in people with obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities comparing once-weekly subcutaneously administered petrelintide, a long-acting amylin analog, versus placebo with regards to effects on body weight, safety, and tolerability1.

“We are excited to announce the rapid completion of enrollment and randomization in the Phase 2b ZUPREME-1 clinical trial with petrelintide in people with overweight or obesity, just three months after initiation”, said David Kendall, MD, Chief Medical Officer of Zealand Pharma. “This achievement reflects both the strong interest in amylin agonists from the clinical community and highlights the importance of developing new treatment options that can leverage distinct mechanisms of action to better serve those living with overweight and obesity”.

ZUPREME-1 is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, multicenter, dose-finding, Phase 2 clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06662539). The trial compares five doses of once-weekly petrelintide with placebo, when added to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity in people with obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities.

The trial includes a screening period, a dose escalation period up to 16 weeks with dose escalation every fourth week followed by a maintenance period until week 42, and a follow-up period after treatment is completed until week 51. ZUPREME-1 has enrolled more than 480 participants across 33 sites in the United States, Poland, and Romania.

The primary endpoint in the trial is the percentage change in body weight from baseline to week 28. Secondary endpoints include, but are not limited to, percentage change in body weight from baseline to week 42, change in waist circumference, change in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), change in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), change in fasting lipids, and change in fasting glucose. Change in body composition at week 42 measured by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is included as an exploratory endpoint in the trial.

Petrelintide is a long-acting amylin analog suitable for once-weekly subcutaneous administration that has been designed with chemical and physical stability with no fibrillation around neutral pH, allowing for co-formulation and co-administration with other peptides2. Amylin is produced in the pancreatic beta cells and co-secreted with insulin in response to ingested nutrients. Amylin receptor activation has been shown to reduce body weight by restoring sensitivity to the satiety hormone leptin3,4, inducing a sense of feeling full faster. Current clinical data or pre-clinical data suggest a potential of petrelintide to deliver weight loss comparable to GLP-1 receptor agonists but with improved tolerability for a better patient experience and high-quality weight loss.

In November 2024, Zealand Pharma presented detailed results from the Phase 1b 16-week multiple ascending dose (MAD) trial at the Obesity Society Annual Meeting (ObesityWeek) 2024. For the presentation, please visit Scientific publications - Pipeline - Zealand Pharma.

In March 2025, Zealand Pharma and Roche entered a collaboration and license agreement to co-develop and co-commercialize petrelintide as a future foundational therapy for people with overweight and obesity. The closing of the transaction is subject to regulatory approvals and other customary closing conditions. The parties expect that the agreement will close in the second quarter of 2025.

Zealand Pharma A/S (Nasdaq: ZEAL) is a biotechnology company focused on the discovery and development of peptide-based medicines. More than 10 drug candidates invented by Zealand Pharma have advanced into clinical development, of which two have reached the market and three candidates are in late-stage development. The company has development partnerships with a number of pharma companies as well as commercial partnerships for its marketed products.

Zealand Pharma was founded in 1998 and is headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark, with a presence in the U.S.

Sources

1. ClinicalTrials.gov. Once-weekly Petrelintide Versus Placebo for Obesity or Overweight With Co-morbidities (ZUPREME). Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06662539. Last accessed March 2025.

2. Eriksson et al. Presentation at ObesityWeek, November 1–4, 2022, San Diego, CA. Link: https://www.zealandpharma.com/media/0gnfxg4b/zp8396-sema-coformulation-obesityweek-2022.pdf.

3. Mathiesen et al. Eur J Endocrinol 2022;186(6):R93–R111.

4. Roth et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(20):7257–7262.

The content above comes from the network. if any infringement, please contact us to modify.

License out/inClinical Result

24 Mar 2025

Novo Nordisk is expanding its prospects in obesity and other metabolic disorders by securing rights to an early-clinical engineered peptide whose effects comes from activating three receptors — the same three targets hit by a next-generation weight drug in development by rival Eli Lilly.

According to deal terms announced Monday, Novo Nordisk is paying United Biotechnology $200 million up front for global rights to its drug, UBT251. United Biotechnology retains rights to the molecule in China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. The Gaungdong, China-based company could receive up to $1.8 billion in milestone payments, plus royalties from sales if Novo Nordisk commercializes UBT251.

Novo Nordisk has the market’s top-selling obesity drug in Wegovy, a product whose main ingredient is a peptide engineered to mimic the hormone that activates the GLP-1 receptor. R&D efforts across the pharma industry are trying to expand this approach to multiple targets. Novo Nordisk’s pipeline includes clinical-stage drugs that hit two targets. UBT251 gives the Danish pharmaceutical giant a once-weekly injection that hits three: GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon. According to Novo Nordisk and United Biotechnologies, preclinical testing of this long-acting peptide showed potent activity on all three receptors.

presented by

Health Tech

The 5 Best Software to Buy for Managing a Spa Franchise

Choosing the right software translates directly into better client management, operational efficiency and growth for your spa franchise. Discover which tool is best for your business.

By Meevo

Under United Biotechnology, UBT251 recently completed double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1b clinical trial in China. The 12-week study enrolled 36 participants randomly assigned to three different dose groups. In the highest dose group, the companies said the weight of those who completed the trial decreased by an average 15.1% from baseline. By comparison, the average weight in the placebo group increased 1.5% from baseline. The companies said the most common adverse events were gastrointestinal, which is consistent with other obesity medications. These events were characterized as mild to moderate in severity.

“The addition of a candidate targeting glucagon, as well as GLP-1 and GIP, will add important optionality to our clinical pipeline, as we look to develop a broad portfolio of differentiated treatment options that cater to the diverse needs of people living with these highly prevalent diseases,” Martin Holst Lange, executive vice president for development at Novo Nordisk, said in a prepared statement. “We look forward to building on United Biotechnology’s scientific work and further exploring the potential best-in-class properties of UBT251 across cardiometabolic disease indications.”

In China, UBT251 is being developed for type 2 diabetes, overweight or obesity, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, and chronic kidney disease. The drug is cleared to enter clinical testing in the U.S. in type 2 diabetes in adults, overweight or obesity, and chronic kidney disease.

Lilly’s candidate to activate the GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors is an engineered peptide named retatrutide. Acknowledging the caveats that come with cross-trial comparisons, Phase 2 results of this weekly injectable drug showed an average 17.5% reduction in body weight from baseline measured after 24 weeks. After 48 weeks, the average weight reduction was 24.2%.

Sponsored Post

A Data-Driven Guide to Patient Access Success

A new report from Relatient, A Data-Driven Guide to Patient Access Succes, highlights how focusing on data accuracy and relevance can enhance the performance of healthcare practices.

By Relatient

Novo Nordisk’s deal for the United Biotechnology drug gives it another try at drugging three targets in single metabolic drug. In a note sent to investors, William Blair analysts noted that the pharma giant discontinued development of a triple agonist for chronic weight management in 2020 due to the company’s clinical success from pairing Wegovy and cagrilintide, a peptide engineered to target the amylin receptor. Also, the triple agonist did not reach the desired target profile.

Mid-stage data posted by Lilly’s retatrutide in 2023 revived interest in obesity drugs that hit three targets, the William Blair analysts said. But retatrutide’s results also showed more severe and frequent adverse events compared to approved drugs, such as Lilly’s own Zepbound. These side effects include higher measures of hypersensitivity, antidrug antibodies, and cardiac arrhythmia.

Retatrutide’s results to date leave an opportunity for companies developing triple-acting obesity drugs to differentiate on safety. That said, William Blair believes dual-acting obesity drugs offer the broadest clinical utility. Triple agonists could benefit patients with high body mass indexes. Retatrutide is expected to post preliminary data in obesity and type 2 diabetes in 2026.

There are other companies developing drugs that hit GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors to trigger weight loss. Kailera Therapeutics launched last fall with $400 million and four in-licensed Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals drug candidates, including one that hits those three targets. The pipeline of Metsera, which raised $275 million from its IPO last month, includes a long-acting peptide engineered to bind to and activate the three targets.

Novo Nordisk Expands Discounted Wegovy Price to Brick-and-Mortar Pharmacies

When Novo Nordisk earlier this month unveiled a discounted price for Wegovy available to eligible patients who order through a new online pharmacy, the drugmaker said this lower price would expand “in the near future” to those who use traditional pharmacies. That change is happening now.

Novo Nordisk said Monday that all cash-paying patients who use Wegovy will be able to obtain the once-weekly injectable obesity drug from brick-and-mortar pharmacies for $499 per month, the same price for the drug through its new NovoCare online pharmacy, which ships the drug directly to patients’ homes. That price is a steep discount from the $1,349 list price for a month’s supply of the drug, a product administered in single-use, pre-filled injection pens.

The new lower cash price for Wegovy covers all doses of the drug. As with the online offering, discounted Wegovy is available to uninsured patients who pay cash for their medicines as well as insured patients whose coverage does not include obesity drugs. Novo Nordisk said this updated offer replaces a previous savings offer that provided Wegovy to cash-paying patients for $650 per month. Patients who are enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid are ineligible for these offers.

Novo Nordisk’s launch of lower-cost Wegovy followed Eli Lilly’s direct-to-consumer move with its obesity drug, Zepbound. Last summer, Lilly announced eligible cash-paying patients could obtain Zepbound through the company’s digital health platform, LillyDirect.

The discounted offerings for cash-pay patients give both Lilly and Novo a way to keep market share from going to compounding pharmacies. Compounding pharmacies may sell their version of a marketed drug when that product is in shortage. Compounded drugs are not tested in clinical trials, nor are they approved by the FDA. With the FDA recently declaring shortages resolved for Zepbound and Wegovy, compounding pharmacies must stop selling their versions of these drugs, though they may continue to offer compounded drug if a patient needs a dose level unavailable in a branded product.

Compounders are suing the FDA, claiming that shortages persist and the agency’s declarations that the shortages are over were done without due process. Both Lilly and Novo contend that offering their respective drugs directly to patients can avoid what they say are the safety risks of compounded drugs. But the new discounted prices for Wegovy and Zepbound are still higher than the prices of compounded versions.

Clinical ResultPhase 1Phase 2

Analysis

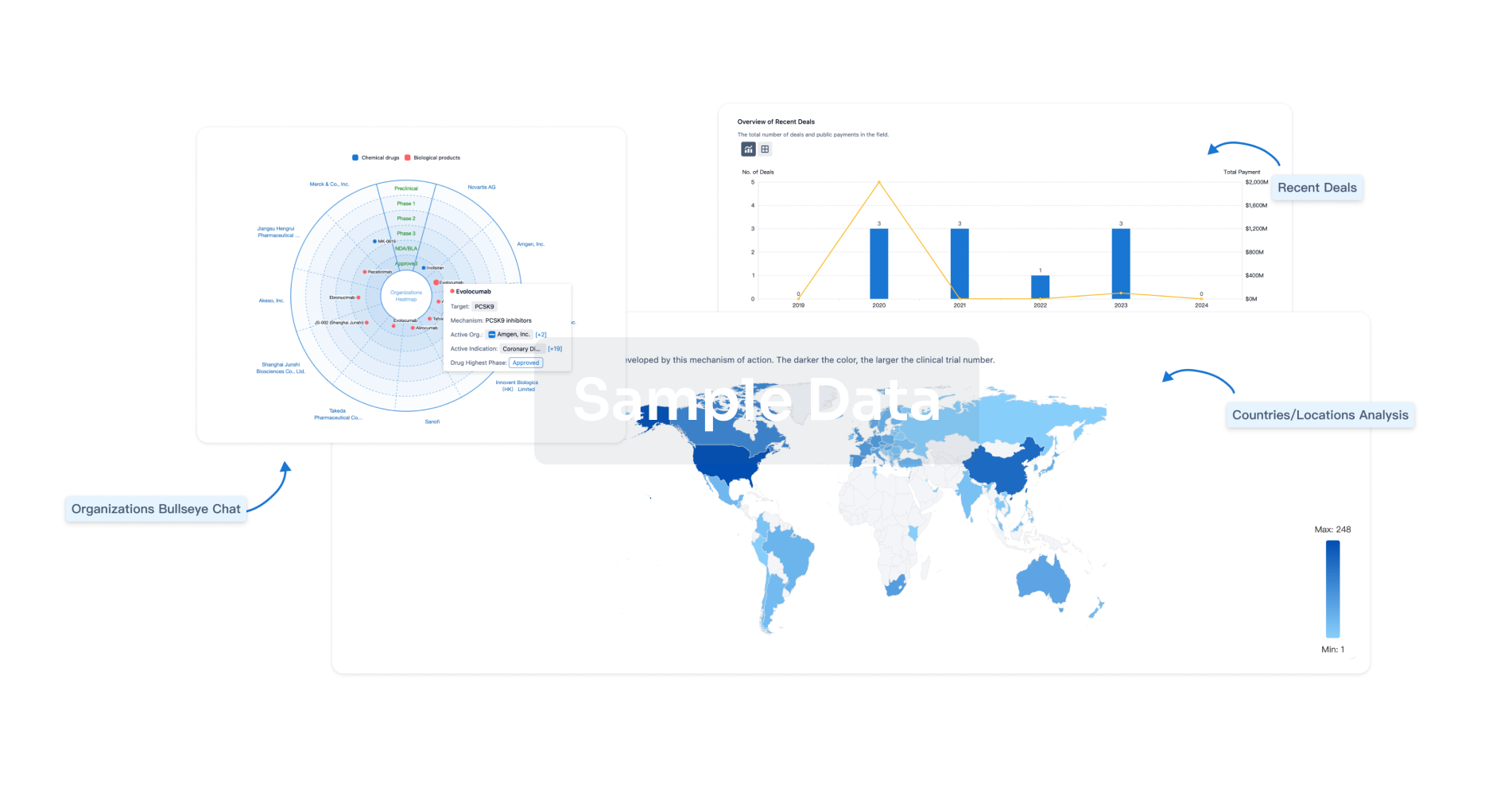

Perform a panoramic analysis of this field.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free