Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

oxlT

Last update 08 May 2025

Basic Info

Synonyms- |

Introduction Anion transporter that carries out the exchange of divalent oxalate with monovalent formate, the product of oxalate decarboxylation, at the plasma membrane, and in doing so catalyzes the vectorial portion of a proton-motive metabolic cycle that drives ATP synthesis. |

Related

1

Drugs associated with oxlTMechanism frc stimulants [+5] |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePending |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date20 Jan 1800 |

2

Clinical Trials associated with oxlTNCT05377112

A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacodynamics of SYNB8802v1 in Subjects With History of Gastric Bypass Surgery or Short-bowel Syndrome

Study SYNB8802-CP-002 is designed to assess safety, tolerability, and oxalate lowering, in subjects with a history of gastric bypass surgery or short-bowel syndrome. In addition, this study will explore other PD effects relative to baseline as well as predictors of efficacy and tolerability.

Start Date29 Mar 2022 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT04629170

A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacodynamics of SYNB8802 in Healthy Volunteers and in Patients With Enteric Hyperoxaluria

This Phase 1a/b, first-in-human, multiple dose-escalation, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study is evaluating SYNB8802 in healthy volunteers (HV) and subjects diagnosed with enteric hyperoxaluria (EH). Eligible subjects receive investigational product (IP) and undergo safety monitoring, evaluations, and subsequent follow-up after IP administration.

In Part 2, all evaluations and assessments throughout this study may be conducted either at the clinical site or by a home healthcare professional at an alternative location (e.g., EH patient's home, hotel).

In Part 2, all evaluations and assessments throughout this study may be conducted either at the clinical site or by a home healthcare professional at an alternative location (e.g., EH patient's home, hotel).

Start Date04 Nov 2020 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with oxlT

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with oxlT

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with oxlT

Login to view more data

32

Literatures (Medical) associated with oxlT25 Jan 2024·The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics and AlphaFold Uncover a Missing Conformational State of Transporter Protein OxlT

Article

Author: Jaunet-Lahary, Titouan ; Okazaki, Kei-Ichi ; Yamashita, Atsuko ; Ohnuki, Jun

01 Jan 2023·Frontiers in microbiology

Expanding the taxonomic and environmental extent of an underexplored carbon metabolism-oxalotrophy.

Article

Author: Sonke, Alexander ; Trembath-Reichert, Elizabeth

01 Oct 2021·Protein ScienceQ4 · BIOLOGY

An optogenetic assay method for electrogenic transporters using Escherichia coli co‐expressing light‐driven proton pump

Q4 · BIOLOGY

Article

Author: Yamashita, Atsuko ; Hayashi, Masahiro ; Kojima, Keiichi ; Sudo, Yuki

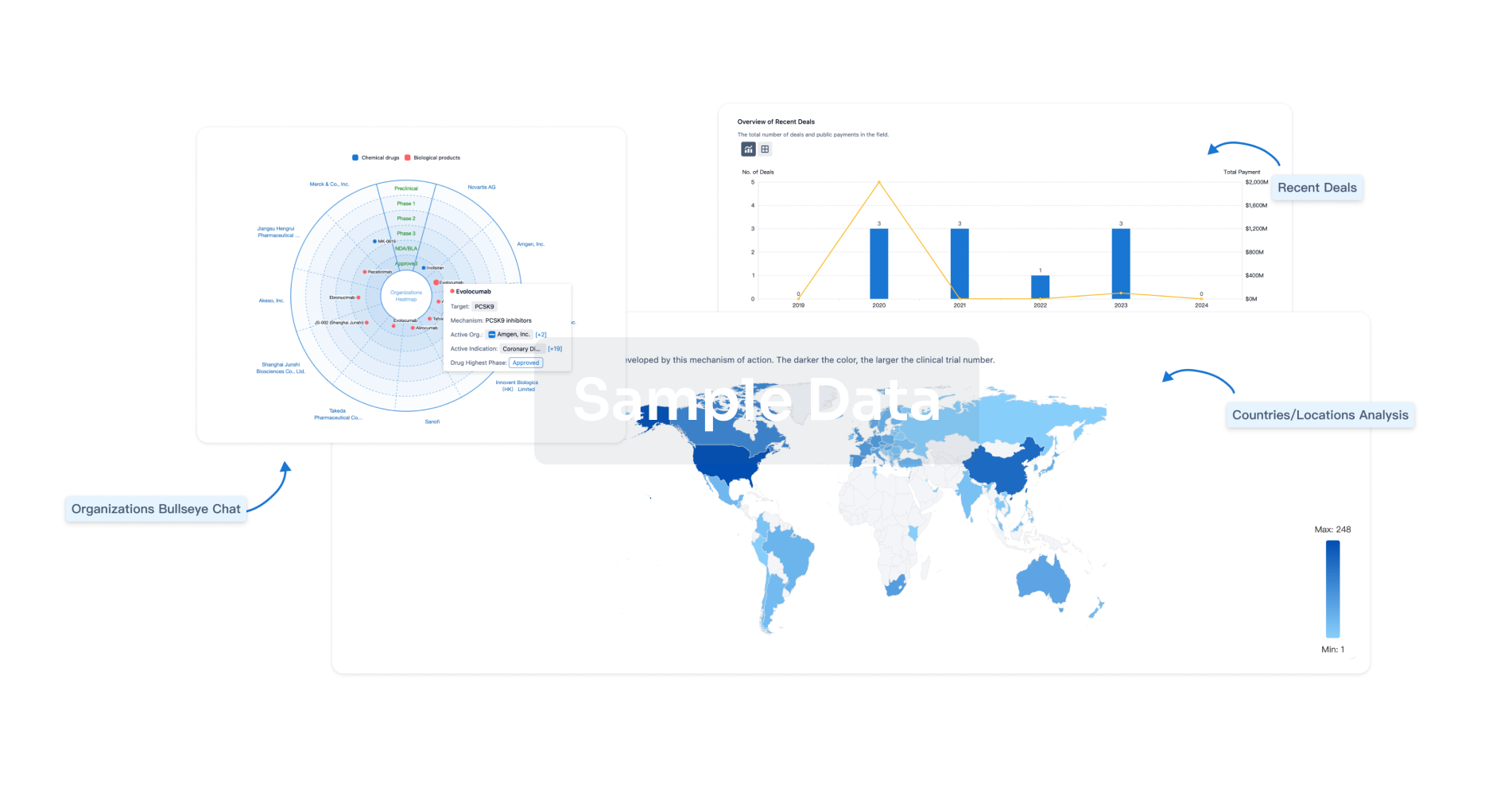

Analysis

Perform a panoramic analysis of this field.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free