Are there any biosimilars available for Anakinra?

Understanding Anakinra

Anakinra is a recombinant, non-glycosylated form of the human interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist (IL‑1Ra) that works by competitively binding to the interleukin‑1 receptor and thereby blocking the effects of proinflammatory cytokines IL‑1α and IL‑1β. This mechanism reduces inflammation and has made anakinra an effective treatment in several conditions where IL‑1 plays a key role. Clinically, anakinra is approved for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID), and deficiency of the IL‑1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) among other autoinflammatory diseases. Its ability to interrupt the IL‑1–driven inflammatory cascade means that anakinra can mediate joint protection, reduce local tissue damage, and positively influence overall disease management. In addition, several clinical studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in conditions such as pyoderma gangrenosum and cytokine storm syndromes. The molecule’s rapid engagement with its receptor offers therapeutic benefits in acute as well as chronic inflammatory conditions.

Current Market and Patent Status

Despite its proven clinical utility, the market landscape for anakinra has some distinguishing features compared with other biologics. Anakinra is produced as a recombinant protein and has a relatively short half-life, necessitating daily subcutaneous injections for patients. This less-than-ideal dosing schedule, coupled with its modest efficacy compared with newer biologics and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs and tsDMARDs), has led to its limited uptake in certain indications (for example, refractory RA prescribing is not as widespread as for other biologics). Moreover, while anakinra has been in use for many years, it has not drawn the same level of biosimilar development activity as the blockbuster agents like adalimumab, infliximab, or etanercept. One of the contributing factors is that the market for anakinra—due to its administration schedule and overall clinical positioning—is smaller and less commercially attractive. Patent protection for anakinra as originally formulated has allowed the reference product to remain the only licensed version on the market. In addition, some formulation patents (for example, those that eliminate excipients such as sodium citrate, as discussed in certain patent filings) pose further technical and commercial challenges for any potential biosimilar entrant. Overall, both clinical practice experience and economic considerations have not yet encouraged the development of standalone biosimilars for anakinra as compared with other biologics.

Biosimilars Overview

Definition and Importance

Biosimilars are defined as biological products that are “highly similar” to an already approved “reference” biologic drug, with only minor differences in clinically inactive components. The critical requirement is that there are no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency between the biosimilar and its reference product. They differ fundamentally from generic small-molecule drugs because biologics are made using complex, living cell processes and typically have high molecular weights and subtle structural differences. In this sense, even small changes—for example, in glycosylation patterns or protein folding—can potentially influence the clinical performance. Nonetheless, rigorous analytical, nonclinical, and clinical studies are required to demonstrate biosimilarity under a “totality of evidence” approach.

The importance of biosimilars from an economic and public health viewpoint is substantial. As biologic therapies are notoriously expensive, biosimilars provide an avenue to reduce treatment costs, thereby increasing patient access to life-saving therapies. Their introduction enhances market competition, often leading to reduced drug prices system-wide and enabling healthcare systems to better allocate resources. Biosimilars also have regulatory definitions that emphasize the demonstration of high similarity via comprehensive comparability assessments that encompass in vitro, in vivo, and clinical evaluations.

Regulatory Pathways for Approval

The approval of biosimilars requires navigating a highly structured regulatory framework. Regulatory agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have established clear guidelines that specify the type of analytical and clinical data needed to demonstrate similarity to the reference product. The approach is typically stepwise:

• First, a thorough analytical characterization is performed to assess structural, functional, and physicochemical attributes.

• Second, nonclinical studies (in vitro and in animal models) are conducted to confirm comparable pharmacodynamics and potential toxicity profiles.

• Finally, clinical studies—especially pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) assessments—along with confirmatory comparative clinical trials, are undertaken to ensure the biosimilar performs equivalently to the reference drug in human patients.

Once the totality of evidence proves that the product is highly similar without clinically meaningful differences, the biosimilar can be approved, and in some cases it may gain the additional designation of interchangeability if further switching studies are provided. The regulatory pathway is designed to ensure that biosimilars meet the same high standards of safety and efficacy as their reference biologics, thus preserving patient safety while broadening access to critical therapies.

Biosimilars for Anakinra

Existing Biosimilars

When it comes to biosimilars specifically for anakinra, current data from the literature and recognized regulatory websites point to one clear conclusion: there are no approved or available biosimilars for anakinra at the present time. Several authoritative sources have commented on the status of biologics in rheumatology and inflammatory diseases. Notably, in detailed reviews of biologic treatments for RA, while many biosimilars are being developed for agents such as adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab, anakinra is typically not mentioned as having any biosimilar counterparts. This is corroborated even by the discussions on IL‑1 inhibition; despite anakinra being a well-characterized therapeutic agent for IL‑1–mediated conditions, the biosimilar development activities appear to be either very limited or non-existent. This situation contrasts sharply with drugs that have a larger market share or more favorable dosing profiles.

A survey of biosimilar literature reveals that most biosimilar development efforts target molecules with high unit sales and significant market competition. Anakinra’s relatively niche market—coupled with its cost benefits not being as dramatic compared with other expensive biologics—means that many manufacturers have focused their biosimilar pipelines on candidates with higher commercial potential. Reviews of biosimilar regulatory pathways make clear that while all biologic drugs are potentially eligible for biosimilar development, economic and developmental priorities drive which products eventually see biosimilar competition. In the case of anakinra, there appears to be no active biosimilar candidate on the market, as no manufacturer has yet advanced anakinra biosimilar through the rigorous comparability exercise required for regulatory approval.

Approval Status and Market Availability

The current approval status of anakinra is that the reference product remains the sole approved form on the market. Regulatory approvals for anakinra have been based on its well-established safety and efficacy profile in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Importantly, while anakinra itself has been applied successfully in several immunologic indications—including a recent emergency use authorization for COVID‑19 pneumonia in specific patient subgroups—none of the submissions or regulatory filings have indicated that a biosimilar candidate has been approved or is in advanced clinical stages.

Available data from synapse and other authoritative sources mention the status of biosimilars in different therapeutic classes, but they often note that for some less commercially prioritized agents like anakinra, “there are no biosimilars currently available”. Similarly, discussions that compare biologic treatments in rheumatoid arthritis underscore that anakinra’s lower efficacy and the associated burdens of daily injections have not stimulated the same biosimilar manufacturing momentum as other agents. Even though biosimilar pathways exist and are well established, in the context of IL‑1 inhibitors it appears that no biosimilar version of anakinra has successfully reached the market. Thus, as of the most recent updates, anakinra remains available only as the reference product.

Implications and Future Directions

Impact on Treatment Costs

Biosimilars have generally been associated with significant cost reductions in managing chronic diseases. For many high-priced biologics, the introduction of biosimilars has increased patient access and eased the burden on healthcare budgets by offering more affordable alternatives. However, since anakinra does not currently have a biosimilar, patients and healthcare systems must continue to rely on the reference formulation. In theory, this could mean that the potential for additional cost savings via biosimilar competition in the IL‑1 inhibition space remains untapped.

The economic impact of biosimilars is multifaceted. On one hand, increased competition through biosimilar introduction typically drives down prices not only for the biosimilar itself but also for the reference product over time. On the other hand, anakinra’s smaller market share and distinct dosing regimen might have deterred biosimilar investment because the potential savings might be less dramatic compared to blockbuster drugs. Thus, the lack of a biosimilar for anakinra suggests that cost saving in the IL‑1 therapeutic area must continue to be optimized through alternative strategies, such as improved manufacturing efficiencies or adjustments in pricing and reimbursement policies.

Moreover, given that anakinra is used for relatively rare conditions like DIRA and NOMID as well as off-label for other inflammatory conditions, the overall cost-effectiveness of biosimilar development might be lower. From a health economics perspective, the value proposition for biosimilar development is stronger when annual sales are high, which may explain why many biosimilar programs are focused on drugs with larger patient populations. As such, until the market dynamics change significantly, or reduced dosing frequency or improved formulation innovations create a broader appeal, the impact on treatment costs for anakinra will likely remain as borne solely by the originator biotech company.

Future Developments in Biosimilars for Anakinra

Looking ahead, the possibility for future biosimilars may depend on several factors that can change the current scenario. First, if further clinical studies demonstrate that modified formulations of anakinra with improved dosing schedules (oral, less frequent injections, improved stability) offer superior patient adherence and outcomes, biosimilar developers might recognize an increased commercial opportunity and pursue such candidates. Advances in analytical methods and cell culture technologies could make it more feasible to replicate the unique structural attributes of anakinra while meeting regulatory requirements.

Second, patent expiry or changes in intellectual property protection for the reference anakinra could provide an opening for biosimilar manufacturers. Although the exact patent status details and remaining exclusivity periods for anakinra formulations vary by region, any significant expiration of key patents would likely prompt interest among global manufacturers. Regulatory incentives in certain regions can also encourage biosimilar development by reducing the economic risk associated with biosimilar clinical trials.

Third, shifts in healthcare policy—especially in markets such as Europe and the United States, where biosimilars are strongly encouraged to improve access and lower costs—might create conditions that favor more aggressive investment into a biosimilar program for anakinra. For instance, if healthcare payers begin to strongly favor the use of biosimilars through formulary decisions or if reimbursement strategies are updated to favor biosimilar uptake, then manufacturers might find a lucrative niche. Increased awareness and education about biosimilars among physicians and payers might also drive this change.

Finally, early-stage research or pilot studies that attempt to produce and characterize anakinra biosimilars may eventually progress into clinical trials. Even if such initiatives are currently in exploratory phases, the evolving regulatory atmosphere and competitive pressures from other biosimilar markets might eventually stimulate the development of anakinra biosimilars in the near future. However, as of the most recent data, there is no clinical-stage candidate that has completed the full regulatory pathway for anakinra biosimilars.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while anakinra is a well-recognized IL‑1 receptor antagonist with proven indications in rheumatoid arthritis, NOMID, DIRA, and other inflammatory diseases, the current landscape indicates that there are no approved biosimilars available for anakinra. The answer to the question “Are there any biosimilars available for Anakinra?” is thus a negative one at present.

The discussion begins with a detailed understanding of anakinra’s mechanism of action, its clinical uses, and its current market and patent situation. Unlike some other highly competitive biologics, anakinra’s unique clinical profile (including its daily administration and niche market status) has limited the commercial incentive for biosimilar development.

The biosimilars overview underscores that while biosimilars are intended to replicate the safety and efficacy of reference biologics at a lower cost, rigorous regulatory pathways must be followed—something that manufacturers have already aggressively pursued for drugs with large patient bases such as adalimumab. In comparative reviews, anakinra is not cited as a target for biosimilar development, and reference analyses explicitly note that there are no current biosimilar candidates for anakinra.

From an economic perspective, the absence of biosimilars means that the potential of cost savings in the IL‑1 inhibition treatment area remains untapped. However, emerging trends in patent expiries, improved manufacturing techniques, and dynamic regulatory environments could in the future catalyze interest in developing anakinra biosimilars. Until then, treatment costs, market competition, and patient access in this space will continue to rely solely on the reference product.

Thus, while biosimilars have made significant inroads in diverse therapeutic areas leading to improved patient access and reduced treatment costs, anakinra remains an exception due to its lower market penetration and less attractive commercial profile. Future advances in formulation technology, changes in patent landscapes, and evolving payer policies could eventually create an opportunity for biosimilar versions of anakinra; however, current evidence and regulatory documentation confirm that no such biosimilars are available.

This detailed analysis integrates scientific, regulatory, economic, and future perspective viewpoints to present a comprehensive answer that stresses the importance of ongoing monitoring in the biosimilar field. For now, clinicians and healthcare providers are advised to use the available reference product while keeping an eye on future developments that might eventually lead to cost-saving biosimilar alternatives for anakinra.

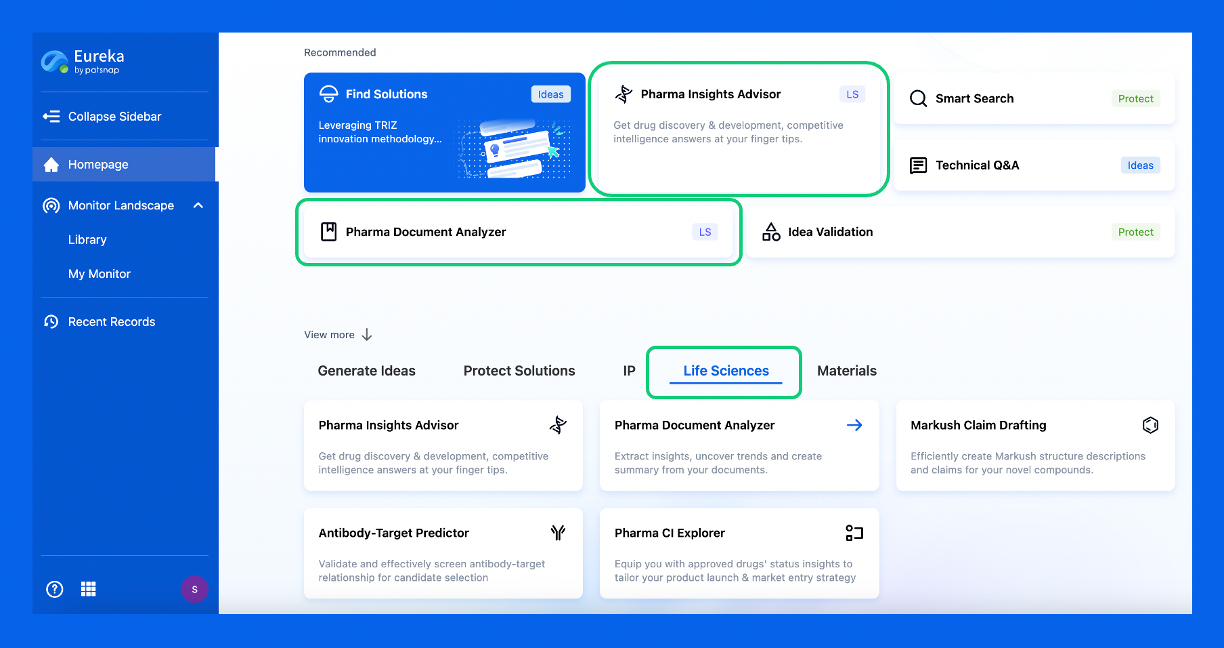

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.