Request Demo

How do different drug classes work in treating Attention Deficit Disorder With Hyperactivity?

17 March 2025

Overview of ADHD

Definition and Symptoms

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a chronic neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that are inappropriate for a person’s developmental stage. The diagnostic criteria rely on behavioral observations and standardized rating scales because the underlying neurobiology is complex and multifaceted. Core symptoms include a difficulty sustaining attention, an inability to remain still or seated in situations where it is expected, impulsive decision‐making and poor executive control. In addition, many individuals with ADHD may also display secondary behavioral issues such as irritability, oppositional behaviors, mood dysregulation, and in some instances, academic or social impairments that extend into family and occupational life.

Epidemiology and Impact

Epidemiological studies reveal that ADHD affects approximately 5–10% of children and adolescents worldwide, with a notable persistence into adulthood in a significant proportion of cases (approximately 3–5% in adults), indicating the lifelong nature of the disorder. Males are diagnosed at higher rates than females, with some studies suggesting a two- to threefold greater prevalence among boys. The disorder not only imposes cognitive and behavioral challenges on individuals but also leads to broader societal issues, including increased risk for academic underachievement, early school dropout, employment difficulties, interpersonal relationship problems, and even an elevated risk of substance use disorders as older cohorts progress into adolescence and adulthood. These findings emphasize ADHD’s pervasive impact on multiple aspects of life, driving extensive research on improving treatment modalities to mitigate these functional impairments.

Drug Classes Used in ADHD Treatment

ADHD pharmacotherapy predominantly falls into two major drug classes: stimulant medications and non-stimulant medications. While both classes improve the core symptoms of ADHD, they differ in their mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetic profiles, and side effect spectra.

Stimulant Medications

Mechanism of Action

Stimulant medications primarily enhance central nervous system (CNS) activity by modulating dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission. They achieve this by blocking the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons and—in some cases—by enhancing the release of these neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. In the prefrontal cortex, an area critical for executive functioning, maintaining adequate levels of these monoamines is essential for attention, working memory, and behavioral inhibition. The pharmacodynamic profile of stimulants typically involves a rapid increase in extracellular dopamine and norepinephrine levels, which is associated with improvements in concentration, impulse control, and overall behavioral regulation. Notably, stimulant medications such as methylphenidate block the dopamine transporter (DAT) and the norepinephrine transporter (NET), while amphetamine derivatives not only block these transporters but also cause the reverse transport of neurotransmitters, thereby amplifying their synaptic concentrations.

Common Drugs and Their Effects

Among stimulant medications, the most commonly prescribed agents are methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and amphetamine-based formulations (Adderall, Lisdexamfetamine). Methylphenidate is typically administered as either an immediate-release or extended-release preparation, with the immediate release producing a rapid onset of action and the extended release providing symptom coverage over an extended period (approximately 6–16 hours). Amphetamine derivatives, including mixed amphetamine salts and prodrugs like lisdexamfetamine, exhibit similar efficacy but tend to induce a more potent response in some patients due to their additional mechanism of promoting neurotransmitter release. These drugs have been shown to improve not only attention and concentration but also academic performance and social interactions by alleviating inattention and impulsivity. Their rapid onset and robust clinical effects have made them the gold standard in ADHD treatment, but they may also carry risks such as appetite suppression, sleep disturbances, and potential cardiovascular effects.

Non-Stimulant Medications

Mechanism of Action

Non-stimulant medications target ADHD symptoms through different neurochemical pathways compared to stimulants. Atomoxetine, for example, is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NET inhibitor) that increases norepinephrine—and by extension, dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex—without directly affecting the dopamine uptake system in other brain regions. This selectivity is particularly valuable in reducing off-target side effects, such as those related to increased dopaminergic activity in limbic areas associated with reward and addiction. In addition, non-stimulants such as alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (guanfacine and clonidine) act by binding to receptors in the prefrontal cortex; they improve attention and behavioral regulation by reducing sympathetic overactivity and enhancing prefrontal cortical control. These medications may also contribute to improved emotional regulation and impulse control by modulating the noradrenergic tone in relevant neuronal circuits. Other non-stimulant therapies, including some antidepressant drugs and newer agents such as viloxazine extended-release, work by modifying neurotransmitter activities that influence both attention and mood, thereby offering an alternative for individuals who are either intolerant or non-responsive to stimulant therapy.

Common Drugs and Their Effects

Atomoxetine is the first non-stimulant medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of ADHD and has been demonstrated to effectively reduce core symptoms with a safety profile that minimizes the risk of abuse. Clinically, atomoxetine is associated with improvements in inattention and impulsivity and is often chosen for patients with comorbid anxiety or substance use risk. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine extended-release and clonidine extended-release are also approved for ADHD treatment, particularly when used in combination with stimulants; these drugs can be especially beneficial in cases marked by pronounced hyperactivity or co-occurring behavioral dysregulation. Viloxazine extended-release, a newer non-stimulant option, functions as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with a history as an antidepressant, and recent studies have confirmed its efficacy and tolerability in pediatric ADHD populations. These non-stimulants may have a more gradual onset of action compared to stimulants and can be preferred when there is a concern about the potential side effects or misuse of stimulant medications.

Comparative Effectiveness

Efficacy of Stimulants vs Non-Stimulants

In clinical practice, stimulants are widely recognized for their robust effects on reducing ADHD symptoms, with multiple large-scale, randomized controlled trials establishing their superior efficacy over non-stimulant medications in achieving rapid symptom control. Meta-analyses of clinical trials consistently demonstrate that stimulant medications produce a significant improvement in attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity compared to placebo, with effect sizes that are moderate to large. Stimulants improve cognitive performance, social behaviors, and overall functional outcomes, and their benefits are often seen within a short period—typically within an hour of administration—making them highly effective for managing daily ADHD symptoms.

By contrast, non-stimulant medications such as atomoxetine have a slower onset of action and may require several weeks to achieve full therapeutic benefit. Although non-stimulants are generally considered less potent in reducing core ADHD symptoms as compared to stimulants, they offer an important alternative when stimulants are contraindicated, poorly tolerated, or associated with a risk of misuse. In several head-to-head clinical trials and meta-analyses, stimulants have demonstrated relatively higher response rates than non-stimulants; however, non-stimulants can still yield clinically significant improvements, particularly in individuals with coexisting anxiety or those who have a history of substance misuse. Studies that have directly compared the two classes reveal that while stimulants may offer a more immediate and robust improvement in attentional capacities, the long-term adherence and persistence with non-stimulants can be favorable for certain subpopulations.

Case Studies and Clinical Trials

Numerous clinical trials and case studies underscore the efficacy of stimulant medications in the treatment of ADHD. For instance, classroom studies have established that extended-release formulations of methylphenidate and amphetamine derivatives provide stable plasma concentrations that cover a full “active” day—typically ranging between 6 to 16 hours—thereby enhancing both academic performance and social functioning. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated rapid improvements in attention and executive functions with stimulant use. Additionally, multiple meta-analyses have confirmed that stimulants reduce the severity of ADHD symptoms significantly more than non-stimulants in the short-term, although the magnitude of differences may decrease over longer treatment periods.

Non-stimulant medications have also been validated through clinical trials. Atomoxetine, for example, has been shown to yield statistically significant improvements in ADHD symptoms versus placebo over a course of treatment lasting several weeks to months. Trials evaluating alpha-2 adrenergic agonists have indicated that while they may not achieve the same rapid response as stimulants, they play a significant role in reducing hyperactivity and improving impulse control, especially when used as adjunctive therapy. Recent clinical studies evaluating viloxazine extended-release have provided evidence for its efficacy in pediatric patients, with results demonstrating a rapid onset of benefit and a favorable side effect profile that compares well with traditional formulations. The collective findings from these studies suggest that while stimulants are the primary modality for immediate and robust symptom control, non-stimulants offer a viable alternative or adjunct—particularly when considering individual patient characteristics and long-term adherence.

Considerations and Future Directions

Side Effects and Safety Concerns

Despite their efficacy, both stimulant and non-stimulant medications are associated with a range of side effects, which must be considered in the context of long-term treatment strategies. Stimulants, while generally well tolerated, have been associated with side effects such as decreased appetite, insomnia, irritability, and, in some cases, cardiovascular effects like increased heart rate and blood pressure. Rarely, severe psychiatric effects such as psychosis or mood alterations have been reported, though these remain uncommon in clinical practice. Given that stimulants are classified as Schedule II controlled substances, there is also a concern regarding their potential for misuse and diversion, particularly in adolescent and young adult populations. Clinical guidelines recommend careful patient selection, baseline cardiovascular evaluation, and ongoing monitoring to mitigate these risks.

Non-stimulant medications, on the other hand, tend to have a different side effect profile. Atomoxetine may produce gastrointestinal disturbances, sleep-related issues, and, in some instances, increases in heart rate or blood pressure, although typically to a lesser extent than stimulants. Alpha-2 agonists such as guanfacine and clonidine can lead to sedation, fatigue, and hypotension, but these effects are often managed by dose adjustment and careful titration. Newer agents such as viloxazine extended-release have been shown to have an improved tolerability profile, with adverse events that are generally mild and transient. In all cases, both clinicians and patients must weigh the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy, particularly because ADHD is a chronic condition that often requires long-term or even lifelong treatment.

Emerging Therapies and Research

As the neurobiological underpinnings of ADHD become better elucidated through advances in neuroimaging, genetics, and molecular biology, future research continues to inform the evolution of pharmacotherapy for the disorder. Recent studies have focused on innovative formulations that aim to mitigate tolerance by altering the release profiles of stimulant medications. These novel approaches suggest that combining an immediate-release component to achieve rapid neurotransmitter elevation with a sustained-release component designed to minimize acute tolerance may prolong the therapeutic benefit and reduce side effects over the long term.

Moreover, emerging non-stimulant therapies are exploring mechanisms beyond the traditional monoaminergic pathways. For example, research targeting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (specifically alpha-7 nAChR agonists) in combination with stimulant medications is being investigated to potentially enhance cognitive and behavioral outcomes without increasing the risk of adverse events. Additionally, there is growing interest in the role of antioxidants and other agents that reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, which may contribute to the pathophysiology of ADHD and its comorbidities. These studies acknowledge that ADHD is not solely a disorder of dopaminergic or noradrenergic dysfunction; rather, it may involve a broader range of neurochemical disturbances that can be targeted by a multimodal treatment approach.

Furthermore, advancements in drug delivery systems, such as transdermal patches and orally disintegrating tablets, are aimed at improving patient adherence by providing more convenient and steady dosing regimens. Such innovations may especially benefit individuals who have difficulty swallowing pills or who require a medication that is less prone to fluctuations in blood levels over the course of the day. As research in this field continues, future therapies are likely to become more tailored to individual patient profiles, taking genetic markers, comorbidities, and personal preferences into account.

Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is multifaceted, involving a variety of drug classes that target different neurobiological systems. ADHD is defined by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, and it leads to significant functional impairments in children and adults alike. The current pharmacological landscape is dominated by stimulant medications that work by blocking the reuptake and promoting the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, thereby enhancing neurotransmission in key brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex. Drugs like methylphenidate and amphetamine derivatives have demonstrated robust clinical effects, rapid onset of action, and significant efficacy in improving cognitive, academic, and social outcomes; however, they are not without their side effects, which include appetite suppression, sleep disturbances, and potential cardiovascular risks.

Non-stimulant medications offer an important alternative for patients who do not tolerate stimulants, have contraindications, or have concerns related to abuse and diversion. Atomoxetine functions as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that indirectly modulates dopaminergic activity in the prefrontal cortex, whereas alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine and clonidine act to modulate sympathetic outflow and improve executive functioning. Newer agents like viloxazine extended-release and emerging therapies targeting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors illustrate the ongoing evolution of ADHD treatment strategies.

Comparative effectiveness research generally supports the superior short-term efficacy of stimulants over non-stimulants, although non-stimulants have their own niche—particularly for long-term management, in patients with comorbid conditions, or when there are concerns about the misuse of stimulants. Case studies and clinical trials consistently demonstrate that tailored pharmacotherapy, often employing a multimodal approach that may combine medication with behavioral interventions, yields the best outcomes.

Side effects remain a critical consideration for both classes of medications. While stimulants can produce rapid symptom relief, their adverse effects—ranging from cardiovascular effects to potential misuse—warrant careful patient selection and ongoing monitoring. Non-stimulants, which may take longer to demonstrate therapeutic benefit, are associated with side effects that are usually less severe but still require appropriate management through careful titration and patient follow-up.

Looking to the future, research is focused on optimizing medication formulations, minimizing tolerance, and exploring novel mechanisms such as the modulation of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Advances in drug delivery technology and individualized treatment based on genetic and neurobiological markers hold promise for a more personalized approach to ADHD management, ultimately improving the long-term outcomes for patients across the lifespan.

In conclusion, different drug classes work in treating ADHD by targeting distinct aspects of neurotransmission and neurocircuitry implicated in the disorder. Stimulant medications provide rapid and robust improvements by directly enhancing dopaminergic and noradrenergic signaling, making them the first-line treatment for most patients. Non-stimulant medications, with their alternative mechanisms and favorable safety profiles, play a vital role in addressing the needs of patients unable to tolerate stimulants or at risk of misuse. The comparative clinical trials and case studies reinforce the importance of a personalized treatment plan that considers efficacy, tolerability, and individual patient profiles. Ongoing and future research is poised to further refine these treatment strategies, emphasizing the need for a nuanced, multifaceted approach to ADHD care that integrates both pharmacological advances and comprehensive patient monitoring.

Definition and Symptoms

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a chronic neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that are inappropriate for a person’s developmental stage. The diagnostic criteria rely on behavioral observations and standardized rating scales because the underlying neurobiology is complex and multifaceted. Core symptoms include a difficulty sustaining attention, an inability to remain still or seated in situations where it is expected, impulsive decision‐making and poor executive control. In addition, many individuals with ADHD may also display secondary behavioral issues such as irritability, oppositional behaviors, mood dysregulation, and in some instances, academic or social impairments that extend into family and occupational life.

Epidemiology and Impact

Epidemiological studies reveal that ADHD affects approximately 5–10% of children and adolescents worldwide, with a notable persistence into adulthood in a significant proportion of cases (approximately 3–5% in adults), indicating the lifelong nature of the disorder. Males are diagnosed at higher rates than females, with some studies suggesting a two- to threefold greater prevalence among boys. The disorder not only imposes cognitive and behavioral challenges on individuals but also leads to broader societal issues, including increased risk for academic underachievement, early school dropout, employment difficulties, interpersonal relationship problems, and even an elevated risk of substance use disorders as older cohorts progress into adolescence and adulthood. These findings emphasize ADHD’s pervasive impact on multiple aspects of life, driving extensive research on improving treatment modalities to mitigate these functional impairments.

Drug Classes Used in ADHD Treatment

ADHD pharmacotherapy predominantly falls into two major drug classes: stimulant medications and non-stimulant medications. While both classes improve the core symptoms of ADHD, they differ in their mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetic profiles, and side effect spectra.

Stimulant Medications

Mechanism of Action

Stimulant medications primarily enhance central nervous system (CNS) activity by modulating dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission. They achieve this by blocking the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons and—in some cases—by enhancing the release of these neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. In the prefrontal cortex, an area critical for executive functioning, maintaining adequate levels of these monoamines is essential for attention, working memory, and behavioral inhibition. The pharmacodynamic profile of stimulants typically involves a rapid increase in extracellular dopamine and norepinephrine levels, which is associated with improvements in concentration, impulse control, and overall behavioral regulation. Notably, stimulant medications such as methylphenidate block the dopamine transporter (DAT) and the norepinephrine transporter (NET), while amphetamine derivatives not only block these transporters but also cause the reverse transport of neurotransmitters, thereby amplifying their synaptic concentrations.

Common Drugs and Their Effects

Among stimulant medications, the most commonly prescribed agents are methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and amphetamine-based formulations (Adderall, Lisdexamfetamine). Methylphenidate is typically administered as either an immediate-release or extended-release preparation, with the immediate release producing a rapid onset of action and the extended release providing symptom coverage over an extended period (approximately 6–16 hours). Amphetamine derivatives, including mixed amphetamine salts and prodrugs like lisdexamfetamine, exhibit similar efficacy but tend to induce a more potent response in some patients due to their additional mechanism of promoting neurotransmitter release. These drugs have been shown to improve not only attention and concentration but also academic performance and social interactions by alleviating inattention and impulsivity. Their rapid onset and robust clinical effects have made them the gold standard in ADHD treatment, but they may also carry risks such as appetite suppression, sleep disturbances, and potential cardiovascular effects.

Non-Stimulant Medications

Mechanism of Action

Non-stimulant medications target ADHD symptoms through different neurochemical pathways compared to stimulants. Atomoxetine, for example, is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NET inhibitor) that increases norepinephrine—and by extension, dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex—without directly affecting the dopamine uptake system in other brain regions. This selectivity is particularly valuable in reducing off-target side effects, such as those related to increased dopaminergic activity in limbic areas associated with reward and addiction. In addition, non-stimulants such as alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (guanfacine and clonidine) act by binding to receptors in the prefrontal cortex; they improve attention and behavioral regulation by reducing sympathetic overactivity and enhancing prefrontal cortical control. These medications may also contribute to improved emotional regulation and impulse control by modulating the noradrenergic tone in relevant neuronal circuits. Other non-stimulant therapies, including some antidepressant drugs and newer agents such as viloxazine extended-release, work by modifying neurotransmitter activities that influence both attention and mood, thereby offering an alternative for individuals who are either intolerant or non-responsive to stimulant therapy.

Common Drugs and Their Effects

Atomoxetine is the first non-stimulant medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of ADHD and has been demonstrated to effectively reduce core symptoms with a safety profile that minimizes the risk of abuse. Clinically, atomoxetine is associated with improvements in inattention and impulsivity and is often chosen for patients with comorbid anxiety or substance use risk. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine extended-release and clonidine extended-release are also approved for ADHD treatment, particularly when used in combination with stimulants; these drugs can be especially beneficial in cases marked by pronounced hyperactivity or co-occurring behavioral dysregulation. Viloxazine extended-release, a newer non-stimulant option, functions as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with a history as an antidepressant, and recent studies have confirmed its efficacy and tolerability in pediatric ADHD populations. These non-stimulants may have a more gradual onset of action compared to stimulants and can be preferred when there is a concern about the potential side effects or misuse of stimulant medications.

Comparative Effectiveness

Efficacy of Stimulants vs Non-Stimulants

In clinical practice, stimulants are widely recognized for their robust effects on reducing ADHD symptoms, with multiple large-scale, randomized controlled trials establishing their superior efficacy over non-stimulant medications in achieving rapid symptom control. Meta-analyses of clinical trials consistently demonstrate that stimulant medications produce a significant improvement in attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity compared to placebo, with effect sizes that are moderate to large. Stimulants improve cognitive performance, social behaviors, and overall functional outcomes, and their benefits are often seen within a short period—typically within an hour of administration—making them highly effective for managing daily ADHD symptoms.

By contrast, non-stimulant medications such as atomoxetine have a slower onset of action and may require several weeks to achieve full therapeutic benefit. Although non-stimulants are generally considered less potent in reducing core ADHD symptoms as compared to stimulants, they offer an important alternative when stimulants are contraindicated, poorly tolerated, or associated with a risk of misuse. In several head-to-head clinical trials and meta-analyses, stimulants have demonstrated relatively higher response rates than non-stimulants; however, non-stimulants can still yield clinically significant improvements, particularly in individuals with coexisting anxiety or those who have a history of substance misuse. Studies that have directly compared the two classes reveal that while stimulants may offer a more immediate and robust improvement in attentional capacities, the long-term adherence and persistence with non-stimulants can be favorable for certain subpopulations.

Case Studies and Clinical Trials

Numerous clinical trials and case studies underscore the efficacy of stimulant medications in the treatment of ADHD. For instance, classroom studies have established that extended-release formulations of methylphenidate and amphetamine derivatives provide stable plasma concentrations that cover a full “active” day—typically ranging between 6 to 16 hours—thereby enhancing both academic performance and social functioning. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated rapid improvements in attention and executive functions with stimulant use. Additionally, multiple meta-analyses have confirmed that stimulants reduce the severity of ADHD symptoms significantly more than non-stimulants in the short-term, although the magnitude of differences may decrease over longer treatment periods.

Non-stimulant medications have also been validated through clinical trials. Atomoxetine, for example, has been shown to yield statistically significant improvements in ADHD symptoms versus placebo over a course of treatment lasting several weeks to months. Trials evaluating alpha-2 adrenergic agonists have indicated that while they may not achieve the same rapid response as stimulants, they play a significant role in reducing hyperactivity and improving impulse control, especially when used as adjunctive therapy. Recent clinical studies evaluating viloxazine extended-release have provided evidence for its efficacy in pediatric patients, with results demonstrating a rapid onset of benefit and a favorable side effect profile that compares well with traditional formulations. The collective findings from these studies suggest that while stimulants are the primary modality for immediate and robust symptom control, non-stimulants offer a viable alternative or adjunct—particularly when considering individual patient characteristics and long-term adherence.

Considerations and Future Directions

Side Effects and Safety Concerns

Despite their efficacy, both stimulant and non-stimulant medications are associated with a range of side effects, which must be considered in the context of long-term treatment strategies. Stimulants, while generally well tolerated, have been associated with side effects such as decreased appetite, insomnia, irritability, and, in some cases, cardiovascular effects like increased heart rate and blood pressure. Rarely, severe psychiatric effects such as psychosis or mood alterations have been reported, though these remain uncommon in clinical practice. Given that stimulants are classified as Schedule II controlled substances, there is also a concern regarding their potential for misuse and diversion, particularly in adolescent and young adult populations. Clinical guidelines recommend careful patient selection, baseline cardiovascular evaluation, and ongoing monitoring to mitigate these risks.

Non-stimulant medications, on the other hand, tend to have a different side effect profile. Atomoxetine may produce gastrointestinal disturbances, sleep-related issues, and, in some instances, increases in heart rate or blood pressure, although typically to a lesser extent than stimulants. Alpha-2 agonists such as guanfacine and clonidine can lead to sedation, fatigue, and hypotension, but these effects are often managed by dose adjustment and careful titration. Newer agents such as viloxazine extended-release have been shown to have an improved tolerability profile, with adverse events that are generally mild and transient. In all cases, both clinicians and patients must weigh the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy, particularly because ADHD is a chronic condition that often requires long-term or even lifelong treatment.

Emerging Therapies and Research

As the neurobiological underpinnings of ADHD become better elucidated through advances in neuroimaging, genetics, and molecular biology, future research continues to inform the evolution of pharmacotherapy for the disorder. Recent studies have focused on innovative formulations that aim to mitigate tolerance by altering the release profiles of stimulant medications. These novel approaches suggest that combining an immediate-release component to achieve rapid neurotransmitter elevation with a sustained-release component designed to minimize acute tolerance may prolong the therapeutic benefit and reduce side effects over the long term.

Moreover, emerging non-stimulant therapies are exploring mechanisms beyond the traditional monoaminergic pathways. For example, research targeting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (specifically alpha-7 nAChR agonists) in combination with stimulant medications is being investigated to potentially enhance cognitive and behavioral outcomes without increasing the risk of adverse events. Additionally, there is growing interest in the role of antioxidants and other agents that reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, which may contribute to the pathophysiology of ADHD and its comorbidities. These studies acknowledge that ADHD is not solely a disorder of dopaminergic or noradrenergic dysfunction; rather, it may involve a broader range of neurochemical disturbances that can be targeted by a multimodal treatment approach.

Furthermore, advancements in drug delivery systems, such as transdermal patches and orally disintegrating tablets, are aimed at improving patient adherence by providing more convenient and steady dosing regimens. Such innovations may especially benefit individuals who have difficulty swallowing pills or who require a medication that is less prone to fluctuations in blood levels over the course of the day. As research in this field continues, future therapies are likely to become more tailored to individual patient profiles, taking genetic markers, comorbidities, and personal preferences into account.

Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is multifaceted, involving a variety of drug classes that target different neurobiological systems. ADHD is defined by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, and it leads to significant functional impairments in children and adults alike. The current pharmacological landscape is dominated by stimulant medications that work by blocking the reuptake and promoting the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, thereby enhancing neurotransmission in key brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex. Drugs like methylphenidate and amphetamine derivatives have demonstrated robust clinical effects, rapid onset of action, and significant efficacy in improving cognitive, academic, and social outcomes; however, they are not without their side effects, which include appetite suppression, sleep disturbances, and potential cardiovascular risks.

Non-stimulant medications offer an important alternative for patients who do not tolerate stimulants, have contraindications, or have concerns related to abuse and diversion. Atomoxetine functions as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that indirectly modulates dopaminergic activity in the prefrontal cortex, whereas alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine and clonidine act to modulate sympathetic outflow and improve executive functioning. Newer agents like viloxazine extended-release and emerging therapies targeting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors illustrate the ongoing evolution of ADHD treatment strategies.

Comparative effectiveness research generally supports the superior short-term efficacy of stimulants over non-stimulants, although non-stimulants have their own niche—particularly for long-term management, in patients with comorbid conditions, or when there are concerns about the misuse of stimulants. Case studies and clinical trials consistently demonstrate that tailored pharmacotherapy, often employing a multimodal approach that may combine medication with behavioral interventions, yields the best outcomes.

Side effects remain a critical consideration for both classes of medications. While stimulants can produce rapid symptom relief, their adverse effects—ranging from cardiovascular effects to potential misuse—warrant careful patient selection and ongoing monitoring. Non-stimulants, which may take longer to demonstrate therapeutic benefit, are associated with side effects that are usually less severe but still require appropriate management through careful titration and patient follow-up.

Looking to the future, research is focused on optimizing medication formulations, minimizing tolerance, and exploring novel mechanisms such as the modulation of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Advances in drug delivery technology and individualized treatment based on genetic and neurobiological markers hold promise for a more personalized approach to ADHD management, ultimately improving the long-term outcomes for patients across the lifespan.

In conclusion, different drug classes work in treating ADHD by targeting distinct aspects of neurotransmission and neurocircuitry implicated in the disorder. Stimulant medications provide rapid and robust improvements by directly enhancing dopaminergic and noradrenergic signaling, making them the first-line treatment for most patients. Non-stimulant medications, with their alternative mechanisms and favorable safety profiles, play a vital role in addressing the needs of patients unable to tolerate stimulants or at risk of misuse. The comparative clinical trials and case studies reinforce the importance of a personalized treatment plan that considers efficacy, tolerability, and individual patient profiles. Ongoing and future research is poised to further refine these treatment strategies, emphasizing the need for a nuanced, multifaceted approach to ADHD care that integrates both pharmacological advances and comprehensive patient monitoring.

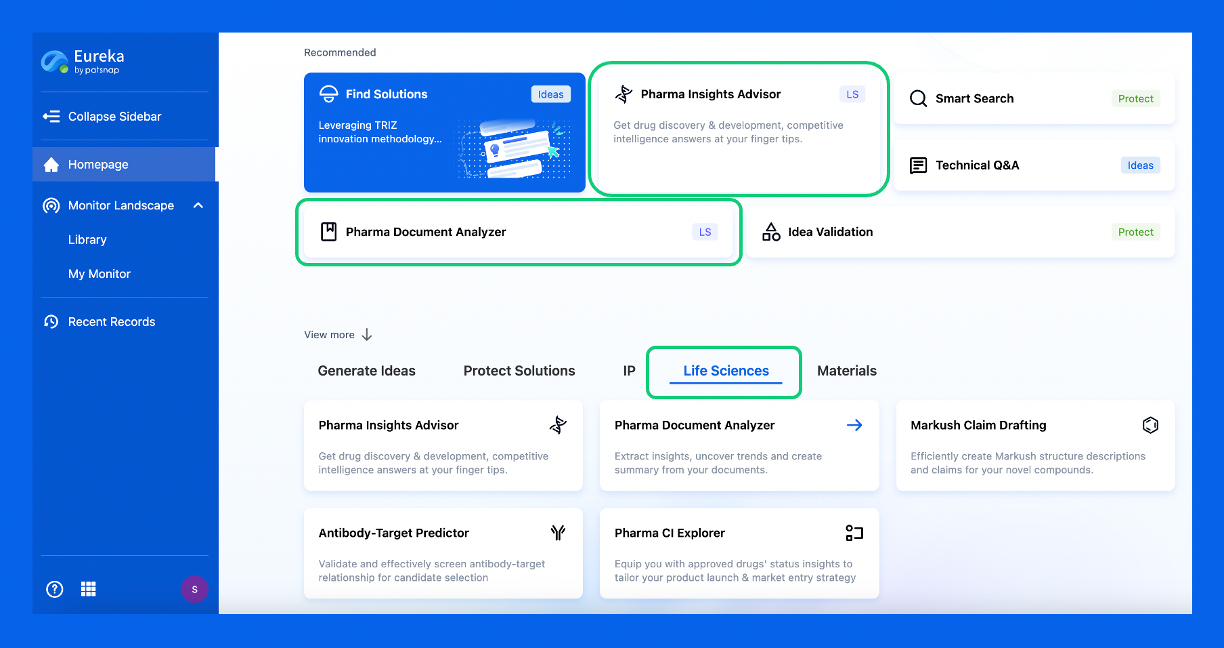

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.