How do different drug classes work in treating Prostatic Cancer?

Overview of Prostatic Cancer

Prostatic cancer refers to malignant growth predominantly arising in the prostate gland—a critical component of the male reproductive system. Clinically, the disease can be classified into various stages. In its early phases, prostate cancer may be localized, meaning that the tumor is confined within the prostate capsule. As the disease progresses, it may become locally advanced or even metastatic. The metastatic stage includes hormone‐sensitive phases and later transitions into castration‐resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), in which cancer cells continue to thrive despite low circulating testosterone levels. The heterogeneity is reflected in both histological grading (determined by Gleason scores) and clinical staging (T, N, and M classifications), which together inform treatment decisions.

Current Treatment Landscape

The treatment paradigm for prostatic cancer is multifaceted. For localized disease, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy are standards. In more advanced stages, systemic treatments become essential. Hormonal therapies, based on androgen deprivation principles, are the backbone of treatment. However, with the emergence of CRPC, chemotherapy and targeted therapies enter the picture. In recent years, combination treatments have been introduced to improve survival outcomes and to alleviate quality‐of‐life issues, such as sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence, which are inherent to many treatment options. The decision regarding treatment often hinges on the stage at diagnosis, risk stratification and the balance of therapeutic efficacy versus potential side effects.

Drug Classes Used in Prostatic Cancer Treatment

Hormonal Therapies

Hormonal therapies are the mainstay for many patients with prostate cancer and represent the primary line of treatment especially for advanced disease. These strategies include androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with surgical or chemical castration (such as luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone [LHRH] agonists/antagonists), nonsteroidal antiandrogens (e.g., bicalutamide, enzalutamide), and combination androgen blockade (CAB) where LHRH analogs are paired with antiandrogens. They function by targeting the androgen receptor (AR) signaling axis, which remains vital even in patients with CRPC due to residual intratumoral androgen synthesis. Clinical studies highlight that, despite a significant reduction of serum testosterone via ADT, the tumor microenvironment may continue to produce low levels of androgen, driving disease progression. Hence, next-generation antiandrogens that more completely block AR activity have been developed.

Chemotherapy Agents

Chemotherapy in prostate cancer is generally reserved for advanced or hormone-refractory disease. The taxane class—exemplified by docetaxel and cabazitaxel—is primarily used. Docetaxel, for example, functions by stabilizing microtubules and thereby disrupting mitotic spindle formation, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cabazitaxel is designed to overcome multidrug resistance and is used after docetaxel failure. In addition, other agents like mitoxantrone have been explored for their palliative benefits, particularly in terms of pain relief, although survival gains appear modest compared to taxanes. Beyond these established agents, there are ongoing investigations into other cytotoxic classes such as antimetabolites, DNA-damaging agents (alkylating agents, topoisomerase inhibitors), and microtubule inhibitors; however, these remain less prominently used in standard treatment.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies are a more recent addition to the therapeutic landscape and work by specifically disrupting molecular pathways critical for tumor growth and survival. Examples include inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, PARP inhibitors that block DNA repair mechanisms, and monoclonal antibodies aimed at growth factor receptors or immune checkpoints. Agents such as capivasertib—a small molecule inhibitor targeting the Akt family—offer an avenue for patients with certain genetic features. Other innovative approaches like antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific antibodies, and fusion proteins are being used or evaluated to improve clinical outcomes while minimizing off-target toxicity. These therapies are designed not only to target the cancer cells more selectively but also to impact the tumor microenvironment and angiogenesis pathways.

Mechanisms of Action

How Hormonal Therapies Work

Hormonal therapies function primarily through the disruption of androgen signaling:

• ADT reduces the synthesis or circulation of androgens, which are critical for prostate cell growth. This is achieved either by surgical castration (removal of the testes) or by using LHRH agonists, which initially cause a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) followed by receptor downregulation and subsequent decrease in testosterone production.

• Nonsteroidal antiandrogens, such as bicalutamide, block the androgen receptor directly. They prevent androgen molecules like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) from binding to AR, thereby thwarting downstream gene transcription that promotes cell proliferation and survival. Advanced agents (e.g., enzalutamide) have a higher affinity for AR and can also inhibit nuclear translocation and DNA binding of the receptor.

• The combination of LHRH-based therapy with antiandrogens (combined androgen blockade) is designed to ensure that any residual androgens—whether generated endogenously in the adrenal glands or within the tumor microenvironment—are neutralized. This multi-pronged strategy is particularly relevant in patients who progress despite initial hormonal therapy.

Thus, by depriving cancer cells of their key growth stimulus, hormonal therapies lead to apoptosis and cellular senescence, slowing the progression of disease in both hormone-sensitive and even castration-resistant stages when used in combination with other modalities.

Mechanisms of Chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic agents act by disrupting essential cellular processes involved in cell division and survival:

• Taxanes such as docetaxel and cabazitaxel bind to tubulin subunits, enhancing microtubule polymerization and stabilizing microtubule assembly. This stabilization prevents the dynamic reorganization necessary for mitosis and ultimately induces cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase leading to programmed cell death (apoptosis).

• Antimetabolites interfere with nucleotide synthesis and DNA replication. Although these are more typical in the treatment of other malignancies, their role has been investigated in prostate cancer in the context of combination therapy and palliation.

• Topoisomerase inhibitors hinder the re-ligation steps of DNA replication, causing DNA strand breaks that trigger cell death. However, these agents are not yet standard in prostate cancer due to their relatively modest efficacy and higher toxicity profiles.

The efficacy of chemotherapy lies in its ability to target rapidly dividing cells, a hallmark of aggressive disease, although these agents are often nonspecific, thereby causing collateral damage to normal, fast-dividing cells (e.g., bone marrow, gastrointestinal epithelium). This nonspecificity is partly responsible for the dose-limiting toxicities observed with chemotherapy.

Targeted Therapy Mechanisms

Targeted therapies are built upon the understanding of specific molecular aberrations that drive prostate cancer progression:

• Signal Transduction Inhibition: Many targeted drugs interfere with receptor tyrosine kinases or associated downstream pathways (e.g., PI3K/AKT/mTOR). For example, inhibitors such as capivasertib bind to Akt isoforms and block phosphorylation events that would normally promote tumor cell proliferation and survival. This targeted inhibition is more selective for tumor cells that aberrantly depend on this pathway.

• DNA Repair Inhibition: PARP inhibitors serve as a prime example by interfering with the enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which repairs single-strand DNA breaks. In tumors with defects in homologous recombination repair (often due to BRCA mutations), this inhibition leads to accumulation of DNA damage and cell death through synthetic lethality. This mechanism has been validated in various malignancies, including certain subsets of prostate cancer.

• Antibody-Based Therapies: Monoclonal antibodies and engineered bispecific antibodies can bind specific antigens on prostate cancer cells, such as HER2, HER3, or Trop-2, thereby blocking ligand interaction and signal transduction. These antibodies may also elicit immune-mediated cytotoxicity through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).

• Drug Conjugates and Fusion Proteins: ADCs combine the specificity of antibodies with potent cytotoxic drugs. They deliver the chemotherapeutic payload directly to the tumor cell, minimizing systemic exposure. Fusion proteins such as nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln, which target immune pathways like IL15R, modulate the immune response against cancer cells while providing a direct anti-proliferative effect.

In summary, targeted therapies leverage molecular insights to design agents that interfere with specific biological pathways crucial for tumor survival. This precision approach not only improves the therapeutic index but also reduces off-target toxicity compared to conventional chemotherapy.

Efficacy and Side Effects

Comparative Efficacy of Drug Classes

The efficacy of each drug class in treating prostate cancer depends on disease stage, molecular profile, and patient-specific factors:

• Hormonal therapies have proven very effective in delaying disease progression in hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. ADT shows robust initial responses; however, most patients eventually develop resistance leading to CRPC. The addition of new-generation antiandrogens, sometimes in combination with traditional therapies, significantly improves overall survival and quality-of-life metrics in men with advanced disease.

• Chemotherapy with taxanes, notably docetaxel, has emerged as a standard in patients with metastatic and castration-resistant disease. Docetaxel, in combination with prednisone, has reliably demonstrated a survival benefit in large phase III trials, with cabazitaxel providing an option for patients who become resistant to docetaxel. Based on analysis, the combination of docetaxel-based chemotherapy offers improved progression-free and overall survival compared to palliative agents like mitoxantrone.

• Targeted therapies are mainly beneficial in molecularly defined subsets of patients. For example, PARP inhibitors are particularly effective in patients with defects in DNA repair such as BRCA mutations. Agents targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway have shown promise, particularly when paired with biomarkers that predict response. In clinical trials, targeted therapies have achieved objective responses and manageable toxicity profiles, although resistance mechanisms still remain a challenge.

When comparing these modalities, hormonal therapies generally have a robust initial efficacy in appropriate patient populations, whereas chemotherapy tends to be more effective in rapidly proliferating, poor-prognosis cancers. Meanwhile, targeted therapies, though often more tolerable, are best applied when the tumor’s molecular signature renders it susceptible to specific pathway inhibition.

Common Side Effects and Management

Each drug class carries its own spectrum of side effects:

• Hormonal therapies are associated with systemic effects due to the suppression of testosterone. Common side effects include hot flashes, decreased libido and erectile dysfunction, loss of muscle mass, osteoporosis, and metabolic effects. For instance, studies have suggested that bicalutamide monotherapy yields fewer sexual side effects compared to combined androgen blockade, which can be an important consideration for quality of life. These side effects are managed through dose modifications, supportive medications (bisphosphonates for osteoporosis), and sometimes lifestyle interventions.

• Chemotherapy, particularly taxane-based regimens, is linked to neutropenia, neuropathy, alopecia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal disturbances. Because these drugs are cytotoxic to all rapidly dividing cells, careful supportive care – such as the use of growth factors for neutropenia, pain management, and dose adjustments – is required to mitigate toxicity. Such side effects are limiting in some patients; therefore, ongoing research aims to develop regimens that maximize tumor cell kill while minimizing systemic harm.

• Targeted therapies tend to have a more favorable toxicity profile overall because they target molecular aberrations specific to tumor cells. However, they are not without adverse events. For instance, PI3K/AKT inhibitors can induce hyperglycemia, hypertension, and skin reactions, while PARP inhibitors may cause anemia and gastrointestinal symptoms. In addition, although targeted agents usually reduce off-target toxicity, resistance and compensatory signaling can still lead to side effects as higher doses or combination regimens may be needed to achieve clinical efficacy.

Supportive care measures, dose adjustments, drug holidays, and careful patient selection based on comorbidity profiles are all strategies currently implemented to manage these side effects effectively.

Future Directions and Research

Emerging Drug Classes

The future of prostate cancer therapy is being shaped by several important ongoing and emerging strategies:

• Novel hormonal agents and combination strategies continue to be explored. For example, intermittent hormonal therapy and sequencing of antiandrogen treatments aim to prolong the hormone-sensitive phase and delay progression to CRPC.

• Next-generation chemotherapeutic agents and delivery systems (such as nanoparticle-based formulations) are being developed to overcome drug resistance and improve drug concentration in tumor tissue while reducing collateral damage to normal cells.

• Molecular targeted therapies are rapidly evolving with the discovery of new biomarkers that define tumor subtypes. With improvements in genomic testing and high-throughput screening methods such as CRISPR-Cas9, researchers are beginning to overcome some of the obstacles of drug resistance by identifying novel actionable targets. For example, newer PARP inhibitors, Akt inhibitors, and targeted protein degradation approaches have emerged, showing promise in early clinical trials.

• Immunotherapy and vaccine-based strategies are under investigation to harness the body’s immune system in fighting tumor cells. Although early results in prostate cancer have been modest compared to cancers like melanoma, ongoing research focuses on combining immunotherapy with other modalities to potentiate immune responses against cancer cells.

Advancements in precision medicine will likely see a greater integration of multi-drug regimens where targeted therapies are combined with chemotherapy or hormonal treatments in a stratified patient population based on molecular diagnostics. This approach can potentially maximize efficacy and minimize toxicities through a personalized medicine framework.

Ongoing Clinical Trials

There are numerous clinical trials underway that test novel combinations and sequences of therapies:

• Trials evaluating the combination of docetaxel with new antiandrogens or targeted agents are progressing. These studies aim to extend progression-free survival and overall survival in advanced prostate cancer.

• Many trials are assessing the role of PARP inhibitors, especially in patients with genetic defects in DNA repair. The early phase results in selected patient subgroups are promising and, if confirmed in larger studies, may lead to the widespread use of these agents in CRPC.

• Combination approaches that include immunotherapy are also being pursued. These trials not only test drug efficacy but provide insight into overcoming resistance through modulation of the tumor microenvironment.

• Studies focusing on novel drug delivery mechanisms such as aptamer-functionalized lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles to co-deliver drugs like curcumin and cabazitaxel seek to increase tumor uptake and reduce systemic toxicities.

Importantly, many of these trials incorporate biomarker-driven selection criteria to identify patients most likely to benefit from a given regimen. By doing so, they promote a more individualized treatment approach that is expected to improve outcomes significantly in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of prostatic cancer is a multifaceted field wherein different drug classes function through distinct mechanisms to address disease progression at various stages. Hormonal therapies work chiefly by interfering with androgen receptor signaling through ADT, antiandrogens, and combination approaches. They are highly effective in the hormone-sensitive state but eventually face limitations due to the development of castration resistance. Chemotherapy agents, especially taxanes like docetaxel and cabazitaxel, operate by disrupting microtubule dynamics and inhibiting cell division, proving valuable in patients with metastatic or hormone-refractory disease despite significant systemic toxicities. Targeted therapies leverage molecular aberrations unique to tumor cells by blocking key signaling pathways and DNA repair mechanisms. These agents are designed with a higher therapeutic index and are optimized for use in molecularly defined patient subgroups.

Comparative efficacy analyses indicate that while hormonal therapies have robust initial actions, chemotherapy significantly improves survival in advanced settings, and targeted therapies offer promising results for selected patients. However, each class comes with its own spectrum of adverse effects—including metabolic disturbances, neuropathy, myelosuppression, and clinical toxicities that require appropriate management strategies.

Looking ahead, emerging drug classes (including novel antiandrogens, innovative nanoparticle delivery systems, and immunomodulatory agents) combined with biomarker-driven patient selection promise to refine personalized treatment strategies. Ongoing clinical trials are pivotal in establishing optimal combination regimens and sequencing of therapies, with the ultimate goal of maximizing patient outcomes while minimizing side effects.

This comprehensive exploration underscores that treating prostatic cancer involves an integrative approach based on disease stage, molecular characteristics, and patient-specific concerns. Advances in genomics, drug delivery technologies, and combination therapies herald a future where personalized medicine will further improve the balance between clinical efficacy and quality of life for patients facing this heterogeneous disease.

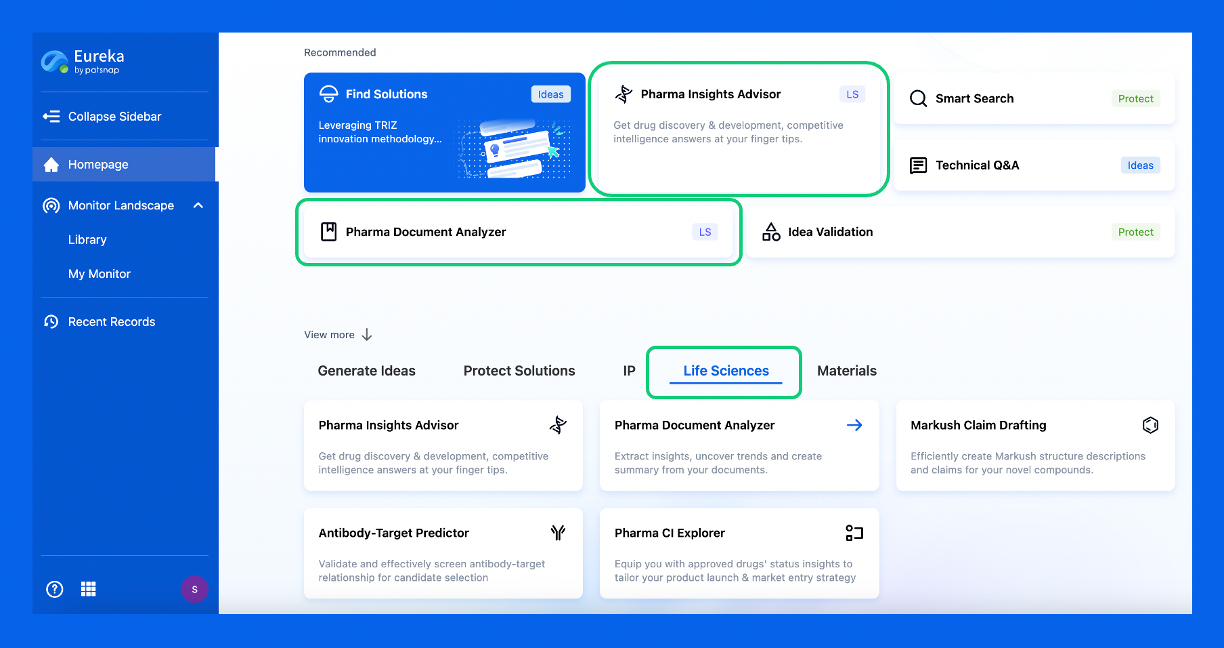

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.