Request Demo

Last update 25 May 2025

Piromelatine

Last update 25 May 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms NEU-P11 |

Action antagonists, agonists |

Mechanism 5-HT1A receptor antagonists(Serotonin 1a (5-HT1a) receptor antagonists), 5-HT1D receptor agonists(Serotonin 1d (5-HT1d) receptor agonists), MTNR1A agonists(Melatonin receptor 1A agonists) |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization |

Inactive Organization- |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2/3 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC17H16N2O4 |

InChIKeyPNTNBIHOAPJYDB-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

CAS Registry946846-83-9 |

Related

7

Clinical Trials associated with PiromelatineCTIS2023-506713-22-00

An open-label sleep laboratory study of efficacy and safety of piromelatine in a well-defined population of patients with idiopathic (isolated) Rapid Eye Movement Behavior Disorder (iRBD). - Piromelatine PSG-RBD

Start Date09 Apr 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT05267535

Randomized, Delayed Start, Double Blind, Parallel Group, Placebo Controlled, Multicenter Study of Piromelatine 20 mg in Participants With Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer's Disease

Randomized efficacy and safety study of piromelatine 20 mg versus placebo in participants with mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease (AD) who are 2:107,510,000-107,540,000 polymorphism non-carriers with the primary objective to compare the effect of piromelatine to that of placebo on the AD Assessment Scale cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog14) at Week 26 of double-blind treatment.

Start Date12 May 2022 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

EUCTR2016-002281-31-ES

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, study of oral treatment of piromelatine in patients with ocular hypertension (OHT) or primary open angle glaucoma (POAG).

Start Date19 Sep 2016 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Piromelatine

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Piromelatine

Login to view more data

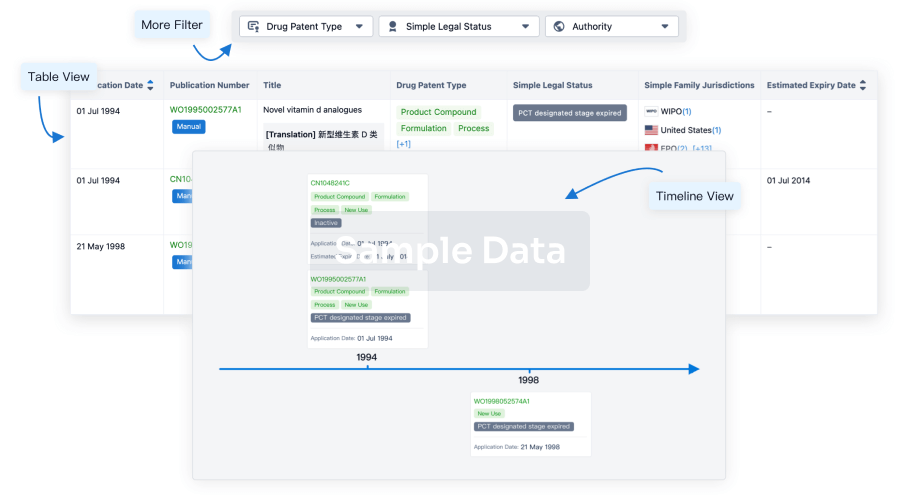

100 Patents (Medical) associated with Piromelatine

Login to view more data

54

Literatures (Medical) associated with Piromelatine01 Oct 2022·Cellular and molecular neurobiologyQ3 · MEDICINE

Chronic Piromelatine Treatment Alleviates Anxiety, Depressive Responses and Abnormal Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis Activity in Prenatally Stressed Male and Female Rats

Q3 · MEDICINE

Article

Author: Ivanova, Natasha ; Tchekalarova, Jana ; Laudon, Moshe ; Nenchovska, Zlatina ; Atanasova, Milena ; Mitreva, Rumyana

The prenatal stress (PNS) model in rodents can induce different abnormal responses that replicate the pathophysiology of depression. We applied this model to evaluate the efficacy of piromelatine (Pir), a novel melatonin analog developed for the treatment of insomnia, in male and female offspring. Adult PNS rats from both sexes showed comparable disturbance associated with high levels of anxiety and depressive responses. Both males and females with PNS demonstrated impaired feedback inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis compared to the intact offspring and increased glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus. However, opposite to female offspring, the male PNS rats showed an increased expression of mineralocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus. Piromelatine (20 mg/kg, i.p., for 21 days injected from postnatal day 60) attenuated the high anxiety level tested in the open field, elevated plus-maze and light-dark test, and depressive-like behavior in the sucrose preference and the forced swimming tests in a sex-specific manner. The drug reversed to control level stress-induced increase of plasma corticosterone 120 min later in both sexes. Piromelatine also corrected to control level the PNS-induced alterations of corticosteroid receptors only in male offspring. Our findings suggest that the piromelatine treatment exerts beneficial effects on impaired behavioral responses and dysregulated HPA axis in both sexes, while it corrects the PNS-induced changes in the hippocampal corticosteroid receptors only in male offspring.

01 Apr 2022·The journal of prevention of Alzheimer's diseaseQ4 · MEDICINE

A Polymorphism Cluster at the 2q12 locus May Predict Response to Piromelatine in Patients with Mild Alzheimer's Disease

Q4 · MEDICINE

Article

Author: Capulli, M ; Ianniciello, G ; Nir, T ; Schneider, L S ; Zisapel, N ; Caceres, J ; Laudon, M

Background: Piromelatine is a novel melatonin MT1/2/3 and serotonin 5-HT-1A/1D receptors agonist developed for mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study (ReCognition) of piromelatine (5, 20, and 50 mg daily for 6 months) in participants with mild dementia due to AD (n=371, age 60-85 years), no statistically significant differences were found between the piromelatine and placebo-treated groups on the primary (i.e., computerized neuropsychological test battery (cNTB)) and secondary outcomes (ADCS-CGIC, ADCS-MCI-ADL, ADAS-cog14, NPI, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)) nor were there safety concerns (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02615002). Objectives: This study was aimed at identifying genetic markers predicting piromelatine treatment response using a genome-wide association approach (GWAS). Design: Variant genotyping of a combined whole genome and whole exome sequencing was performed using DNA extracted from lymphocytes from consenting participants. The general case-control allelic test was performed on piromelatine-treated participants, taking “responders” (i.e., >0.125 change from baseline in the cNTB) as cases and “non responders” as controls, using a Cochran-Armitage trend test. Setting: 58 outpatient clinics in the US. Participants: 371 participants were randomized in the trial; 107 provided informed consent for genotyping. Results: The GWAS sample did not differ from the full study cohort in demographics, baseline characteristics, or response to piromelatine. Six single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in chromosome 2q12 (2:107,510,000-107,540,000) were associated with response (p-value < 1x10 -4 each). Post hoc analyses suggested that the carriers of the 2q12 polymorphism cluster (27% of the GWAS sample) improved significantly on the cNTB on piromelatine as compared to placebo but significantly worsened on the ADAS-Cog14 and PSQI. By contrast, “non-carriers” improved significantly with piromelatine compared to placebo on the ADAS-Cog14 ( 2.91 (N=23) with piromelatine 20 mg vs 1.65 (N=19) with placebo (p=0.03)) and PSQI. Conclusions: The 2q12 (2:107,510,000-107,540,000) 5-6 SNPs cluster may predict efficacy of piromelatine for mild AD. These findings warrant further investigation in a larger, prospective early-stage AD clinical trial for patients who are non-carriers of the 2q12 polymorphism cluster.

01 Feb 2022·Behavioural brain researchQ3 · PSYCHOLOGY

Antidepressant actions of melatonin and melatonin receptor agonist: Focus on pathophysiology and treatment

Q3 · PSYCHOLOGY

Review

Author: Jiang, Ya-Jie ; Liu, Jian ; Zhao, Hong-Qing ; Wang, Ye-Qing ; Zou, Man-Shu ; Wang, Yu-Hong

Depression has become one of the most commonly prevalent neuropsychiatric disorders, and the main characteristics of depression are sleep disorders and melatonin secretion disorders caused by circadian rhythm disorders. Abnormal endogenous melatonin alterations can contribute to the occurrence and development of depression. However, molecular mechanisms underlying this abnormality remain ambiguous. The present review summarizes the mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of melatonin, which is related to its functions in the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, inhibition of neuroinflammation, inhibition of oxidative stress, alleviation of autophagy, and upregulation of neurotrophic, promotion of neuroplasticity and upregulation of the levels of neurotransmitters, etc. Also, melatonin receptor agonists, such as agomelatine, ramelteon, piromelatine, tasimelteon, and GW117, have received considerable critical attention and are highly implicated in treating depression and comorbid disorders. This review focuses on melatonin and various melatonin receptor agonists in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression, aiming to provide further insight into the pathogenesis of depression and explore potential targets for novel agent development.

3

News (Medical) associated with Piromelatine09 Sep 2024

iStock/

wildpixel

The next generation of Alzheimer’s therapeutics is moving away from amyloid plaques and tau tangles, offering multiple approaches to slow cognitive decline.

Over the past two years, Eisai and Biogen’s Leqembi and Eli Lilly’s Kisunla, both anti-amyloid antibodies, made history as the first real options to slow cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. For years, amyloid plaques and tau tangles have been a primary target of Alzheimer’s disease research and drug development, but while affecting these proteins may yield some benefit, the illness continues to progress. Today, multiple therapeutics are in Phase III trials with other targets, suggesting that within the next few years it may become possible to treat Alzheimer’s via multiple pathways.

There are currently 32 Alzheimer’s therapeutics in 48 Phase III trials, according to a recent

paper

by neuroscientist Jeffrey Cummings, a professor at the University of Nevada. Six of those target amyloid-β and one targets tau, but the others aim to affect neuroprotection growth factors, neurotransmitters, neurogenesis, inflammation and proteinopathies. Of those, 21 are meant to be disease-modifying.

“Alzheimer’s disease is quite complex in its biology and diagnosis,” Rebecca Edelmayer, vice president of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, told

BioSpace.

“We’re moving to a point where we have better understanding of the disease and what contributes to its symptomology, so those biological underpinnings become targets.”

These approaches won’t necessarily replace Leqembi and Kisunla, but they could increase therapeutic options to better manage the disease.

The First Anti-Amyloid Antibodies for Alzheimer’s

In January 2023, the FDA

approved Leqembi

as the second disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The third,

Kisunla

, followed in July 2024. (The first drug, Eisai and Biogen’s Aduhelm, was

discontinued

earlier this year.)

While Leqembi and Kisunla are a positive step forward, experts suggest there is room for improvement. As measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB),

Leqembi reduced clinical decline

by 27%, whereas Kisunla

reduced clinical decline

by 29%.

In addition to limited efficacy, the drugs both have notable side effects, specifically, the risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), the increase in lateral ventricular volume and the simultaneous loss of whole brain volume. A finding of ARIA on imaging tests is indicative of a brain bleed or swelling.

When physician online community Sermo questioned 268 neurologists, it found a

diversity of opinion

on how to best determine clinical benefit. Forty percent of those surveyed have treated Alzheimer’s patients with Leqembi or Kisunla.

“There’s debate about whether the two already approved therapeutics are that compelling, so the bar is low,” Andrew Tsai, senior vice president of equity research for the biopharma analyst Jefferies, told

BioSpace

.

A major difference between the two is that Leqembi is infused intravenously twice monthly, while Kisunla is infused only once per month. But any infusion is a pain point for many patients, not to mention a cost to the healthcare system, so easier administration is the goal for several next- gen Alzheimer’s therapeutics. Lilly’s drug is also designed to stop treatment once plaque clearance is achieved.

Phase III Alzheimer’s Candidates

Athira’s Fosgonimeton

Athira Pharma’s

fosgonimeton

is a small-molecule therapeutic that may be injected daily at home. The company recently reported data from a Phase II/III trial of the drug, which

enhances

signaling by neurotrophic hepatocyte growth factor (HGF).

The trial, which included 315 patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease,

failed to meet its primary and key secondary endpoints

regarding improvements in cognition and function at the 26-week point. However, pre-specified

subgroups

experienced rapid disease progression, while both cognition and function either stabilized or improved. Biomarkers also showed improvement, according to the company.

In preclinical models of Alzheimer’s disease, fosgonimeton has “been shown to reduce inflammation, improve mitochondrial and synaptic function and reduce amyloid toxicity and p-tau aggregation,” Chief Medical Officer Javier San Martin told

BioSpace

in an email.

“[While] Leqembi and Kisunla are monoclonal antibodies targeting removal of amyloid plaque from the brain with the expectation that by removing amyloid the neurons will be preserved . . . fosgonimeton focuses on improving neuronal health regardless whether the insult is amyloid, tau or other misfolded proteins,” he said.

Anavex’s ANAVEX 2-73

In New York, Anavex Life Sciences Corp. is targeting neuronal homeostasis in an ongoing Phase IIb/III study with blarcamesine, an oral, once-daily therapeutic that works “through

autophagy through SIGMAR1 activation

.”

“Blarcamesine’s ability to reduce pathological brain volume loss could be defined as disease-modifying,” Andrew Barwicki, company spokesperson, told

BioSpace

.

In the

Phase IIb/III trial

, blarcamesine slowed clinical progression of Alzheimer’s by 38.5% at 48 weeks, compared to placebo.

Analysis

of the Phase IIb/III trial showed no associated neuroimaging adverse events and, unlike

Kisunla

and

Leqembi

, blarcamesine is not expected to require routine MRI monitoring.

“Blarcamesine could be appealing because of its route of administration and good comparative safety profile,” Barwicki suggested.

Anavex anticipates submitting a full regulatory package to the European Medicines Agency by the end of this year.

Novo Nordisk’s Semaglutide

Novo Nordisk is

testing semaglutide

, its wildly popular glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist for weight loss and other indications, in patients with early Alzheimer’s. Completion of the Phase III study is expected in October 2026. Early

studies

by independent scientists suggest semaglutide reduces

neuroinflammation

, which impairs cell signaling. It also may improve vascularization.

Neurim’s Piromelatine

At Neurim Pharmaceuticals, a Phase III trial in Alzheimer’s patients with mild dementia will determine whether piromelatine can improve cognition and function by improving sleep quality. The hypothesis is that sleep disturbances increase synaptic and metabolic activity, impairing the brain’s ability to clear wastes, which then increases amyloid beta aggregation. Piromelatine works by activating certain melatonin and serotonin receptor agonists.

Cassava Sciences’ Simufilam

Finally, Austin, Texas–based Cassava Sciences seeks to restore the brain’s shape and function by stabilizing the scaffolding protein filamin A (FLNA), thus purportedly blocking signaling from soluble amyloid beta.

But Cassava’s conduct around simufilam has spurred an

investigation

by the U.S. Department of Justice. The company’s former science advisor, Hoau-Yan Wang, was

indicted in June

for allegedly falsifying scientific data that led to the awards of some $16 million in NIH grants between 2015 and 2023. The charges include allegedly misconstruing data about how “a potential treatment” and its diagnostic test would work.

The company’s

August corporate overview

reiterates a February

news release

, noting that patients with mild Alzheimer’s who were treated with its oral therapeutic,

simufilam

, continuously for two years had no decline in their ADAS-Cog scores. Non-continuous treatment resulted in a one-point ADAS-Cog decline.

In late July, Cassava added an

open-label extension

to its ongoing Phase II and III clinical trials for Alzheimer’s, which attracted 89% of its Phase III patients.

According to August’s corporate overview, Cassava expects topline results from its 804-patient RETHINK-ALZ trial by year’s end.

Combinations Are Key

Alzheimer’s is a very hetergeneous disease and there is no magic bullet for treatment. Given the many different mechanisms of action of emerging Alzheimer’s therapeutics, “there may be a case for teaming up and using certain therapeutics in combination,” Tsai said.

“We’re excited to see the clinical trial pipeline diversity over time,” Edelmayer added, but the solution may involve more than therapeutics. Ultimately, “Treatment may require a combination of powerful, FDA-approved therapies in conjunction with brain-healthy lifestyles. We envision a future where there are many treatments that address the disease in multiple ways.”

Phase 3Clinical ResultDrug Approval

05 Jan 2024

STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) is a protein that plays a crucial role in the innate immune response of the human body. It acts as a sensor for detecting the presence of foreign DNA, such as viral or bacterial DNA, within cells. When activated, STING triggers a signaling cascade that leads to the production of interferons and other immune response molecules. This activation helps to initiate an immune response against the invading pathogens, aiding in their clearance. Additionally, STING has been implicated in various diseases, including autoimmune disorders and cancer, making it an important target for therapeutic interventions in the pharmaceutical industry.

Recent studies suggest that STING agonists can attenuate tau phosphorylation after blast and repeated concussive injury. They could potentially be used for providing partial protection against radiation injury. Furthermore, there is ongoing research into repurposing STING agonists for other uses. For instance, the Clinicaltrials.gov database lists a study currently recruiting patients entitled “Safety and Efficacy of Piromelatine in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease Patients (ReCOGNITION),” indicating that the compound will be primarily developed for cognition and not for sleep. These developments suggest that STING agonists could play a significant role in the treatment of various diseases in the future.

Based on the analysis of the data provided, the current competitive landscape of target STING in the pharmaceutical industry is characterized by the growth of companies such as Merck & Co., Inc., ImmuneSensor Therapeutics, Inc., Sino Biopharmaceutical Ltd., and Codiak BioSciences, Inc. These companies have a strong focus on R&D and are progressing in various stages of development. The indications for drugs targeting STING include solid tumors, lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and various other types of cancers. The most rapidly progressing drug types are small molecule drugs, followed by exosomes, unknown drugs, monoclonal antibodies, and antibody drug conjugates (ADCs). The United States, China, and other countries/locations are actively involved in the development of drugs targeting STING. The future development of target STING is expected to be driven by the continuous research and development efforts of these companies and the exploration of new indications and drug types.

How do they work?STING agonists are a type of drug that activate the STING pathway in the immune system. STING stands for Stimulator of Interferon Genes and is a protein involved in the innate immune response. When STING is activated, it triggers the production of interferons and other immune signaling molecules, leading to an enhanced immune response against pathogens such as viruses and bacteria.

From a biomedical perspective, STING agonists are being investigated as potential immunotherapies for various diseases, including cancer. By activating the STING pathway, these agonists can stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells. This approach is aimed at boosting the body's natural defense mechanisms to fight cancer.

STING agonists can be administered through different routes, including injection or topical application, depending on the specific drug formulation. They are being studied in preclinical and clinical trials to assess their safety and efficacy in treating different types of cancer and other immune-related disorders.

It's important to note that the development and use of STING agonists are still in the research stage, and further studies are needed to fully understand their potential benefits and any potential side effects.

List of STING AgonistsThe currently marketed STING agonists include:

IMSA-101MK-1454exoSTINGSB-11285BI 1387446 (Boehringer-Ingelheim)BMS-986301CRD-3874DN-015089E-7766GSK-3745417For more information, please click on the image below.

What are STING agonists used for?STING agonists are being investigated as potential immunotherapies for various diseases, including cancer. For more information, please click on the image below to log in and search.

How to obtain the latest development progress of STING agonists?In the Synapse database, you can keep abreast of the latest research and development advances of STING agonists anywhere and anytime, daily or weekly, through the "Set Alert" function. Click on the image below to embark on a brand new journey of drug discovery!

20 Dec 2022

DUBLIN--(

BUSINESS WIRE

)--The

"Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics (2022 Edition) - Market Insight, Epidemiology and Pipeline Assessment (By Molecule Type, By Route of Administration, By Pipeline Phase)"

report has been added to

ResearchAndMarkets.com's

offering.

Alzheimer's disease Therapeutics Pipeline Analysis has 101 active drugs undergoing several stages of clinical trials.

The Alzheimer's disease Therapeutics Pipeline is driven by an increasing gap of unmet need of effective therapeutics that can cure Alzheimer's disease. Additionally, life expectancy has increased due to various healthcare reforms in major economies such as the U.S., Japan, and China. This has resulted in a large geriatric population which is the age group most affected by the disease.

Alzheimer's prevalence is rising rapidly and despite decades of research, the disease remains incurable. The majority of therapeutics target symptom reduction and slowing the progression of the disease. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved aducanumab (Aduhelm) for the treatment of certain cases of Alzheimer's disease in June 2021 and this is the first drug approved for Alzheimer's disease in decades.

Eisai, Biogen, Hoffmann-La Roche, AZTherapies, Cerecin, Neurotrope, AC Immune, Cassava Sciences, AB Science, Anavex Life Sciences, Athira Pharma, Denali Therapeutics Inc., and other notable companies are developing therapeutic candidates to improve the Alzheimer's Diagnosis and treatment scenario.

Scope of the Report

The report analyses the Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics in Pipeline by Molecule Type (Small Molecules, Monoclonal Antibody, Vaccine, DNA/RNA Based, Natural products, Gene Therapy, Cell Therapy, Others).

The report analyses the Alzheimer's disease Therapeutics by Route of Administration (Oral, Intravenous, Intramuscular, Subcutaneous, Intrathecal, Intranasal, Other).

The report analyses the Alzheimer's disease Therapeutics by Pipeline Phase (Phase I, Phase I/II, Phase II, Phase II/III, Phase III, Phase IV, Preclinical).

The report analyses the Pain Management Drugs Market by Availability (Over the Counter (OTC), Prescription).

The Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics Pipeline Analysis has been analysed By Region (Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific, and MEA).

The Global Pain Management Drugs Market has been analysed By Region (Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific, and MEA).

The key insights of the report have been presented through the leading company shares.

Also, the major, trends, drivers and challenges as well as Unmet Needs of the industry has been analysed in the report.

The companies analysed in the report include Eli-Lily & Co , Elsal Co., Ltd., BioVie, Johnson and Johnson, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. H. Lundbeck A/S, Novartis, Cognition Therapeutics, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, Biogen.

Key Target Audience

Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics Companies

End Users (Hospitals and clinics)

Research and Development (R&D) Organizations

Government Bodies & Regulating Authorities

Investment Banks and Equity Firms

Key Topics Covered:

1. Introduction

1.1 Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics Overview

1.2 Scope of Research

2. Executive Summary

2.1 Market Dashboard

2.2 Regional Insights

2.3 Market Ecosystem Factors

3. Research Methodology

3.1 Data Collection Process

3.2 Market Size Calculation-Top-to-Bottom

4. Macro Economic Indicator Outlook

4.1 Global, Region wise GDP Growth

4.2 Global Medical Spending

4.3 Current Healthcare Expenditure

4.4 Pharmaceutical Spending/capita

5. Competitive Positioning

5.1 Companies' Product Positioning

5.2 Competitive positioning

5.2.1 Eli-Lily & Co

5.2.2 Elsal Co., Ltd.

5.2.3 BioVie

5.2.4 Johnson & Johnson

5.2.5 Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

5.2.6 H. Lundbeck A/S

5.2.7 Novartis

5.2.8 Cognition Therapeutics

5.2.9 Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC

5.2.10 Biogen

6. Alzheimer's disease background

6.1 AD Fact Sheet

6.2 Epidemiology

6.3 Causes and Risk Factors

6.4 Diagnosis and Assessment

6.5 Unmet Needs

7. Therapeutics in Pipeline

7.1 Pipeline Scenario

7.2 Alzheimer's Therapeutics Comparative Review

8. Pipeline Analysis

9. Phase I therapeutics Overview

9.1 LY3372993

9.1.1 Drug Description

9.1.2 Outcomes

9.2 Lu AF87908

9.3 anle138b

9.4 ASN51

9.5 CMS121

9.6 IBC-Ab002

9.7 LX1001

9.8 MK-2214

9.9 MK-8189

9.10 ACU193

9.11 NIO752

9.12 ALN-APP

9.13 TB006

9.14 SNK01

9.15 Pepinemab

9.16 GB-5001

9.17 AC-1202

9.18 SHR-1707

9.19 BEY2153

9.20 JNJ-40346527

9.21 APNmAb005

9.22 NPT 2042

9.23 ALZ-101

10. Phase I/II therapeutics Overview

10.1 Posiphen

10.1.1 Drug Description

10.1.2 Outcomes

10.1.3 Collaborators

10.2 PrimeProT/ PrimeMSKT

10.3 TB006

10.4 RO7126209

10.5 DNL593

10.6 BIIB080

10.7 E2814

10.8 Tdap

10.9 ACI-35.030/ JACI-35.054

10.10 ACI-24.060

10.11 IVL3003

11. Phase II therapeutics Overview

11.1 Lecanemab

11.1.1 Drug Description

11.1.2 Outcomes

11.1.3 Collaborators

11.2 Lomecel-B

11.3 AL002

11.4 AL001

11.5 CT1812 (Elaya)

11.6 APH-1105

11.7 ATH-1017

11.8 T-817MA

11.9 Montelukast buccal film

11.10 ABBV-916

11.11 Bepranemab

11.12 TB006

11.13 LY3372689

11.14 MW150

11.15 EX039

11.16 JNJ-42847922

11.17 REM0046127

11.18 Bryostatin 1

11.19 NanoLithium NP03

11.20 AstroStem

11.21 Gantenerumab

11.22 Semorinemab

11.23 Obicetrapib

11.24 ALZ-801

11.25 CY6463

11.26 Crenezumab

11.27 T3D-959

11.28 PMZ-1620

11.29 GV1001

11.30 ACZ885

11.31 PQ912

11.32 APH-1105

11.33 SLS-005

11.34 Flos gossypii flavonoids

11.35 Human Mesenchymal Stem cells (MSCs)

11.36 JNJ-63733657

11.37 IGC-AD1

11.38 TW001

11.39 ABvac40

12. Phase II/III therapeutics Overview

12.1 Tricaprilin

12.1.1 Drug Description

12.1.2 Outcomes

12.2 ANAVEX2-73

12.3 Piromelatine

12.4 AGB101

13. Phase III therapeutics Overview

13.1 Simufilam

13.1.1 Drug Description

13.1.2 Outcomes

13.1.3 Collaborators

13.2 ATH-1017

13.3 Lecanemab

13.4 Nilotinib BE

13.5 Brexpiprazole

13.6 Masitinib

13.7 Remternetug

13.8 Donanemab

13.9 NE3107

13.10 Gantenerumab

13.11 GV-971

13.12 Aducanumab

13.13 TRx0237

13.14 Semagludtide

13.15 BPDO-1603

13.16 AR1001

13.17 KarXT

13.18 AXS-05

14. Phase IV therapeutics Overview

14.1 Choline Alfoscerate

14.1.1 Drug Description

14.1.2 Outcomes

14.2 Ebicomb

14.3 Rivastigmine

14.4 GV-971

15. Preclinical Phase therapeutics Overview

15.1 PMN310

15.1.1 Drug Description

15.1.2 Outcomes

15.1.3 Collaborators

15.2 PRX123

16. Pipeline analysis, By molecule type

16.1 Alzheimer's Therapeutics Comparative Review, by Molecule type

17. Pipeline analysis, By Route of Administration

17.1 Alzheimer's Therapeutics Comparative Review, By Route of Administration

For more information about this report visit

https://www.researchandmarkets.com/r/wcw7f7

Drug ApprovalPhase 2Phase 1

100 Deals associated with Piromelatine

Login to view more data

External Link

| KEGG | Wiki | ATC | Drug Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | Piromelatine | - |

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer Disease | Phase 3 | United States | 12 May 2022 | |

| Alzheimer Disease | Phase 3 | Canada | 12 May 2022 | |

| Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders | Phase 2 | United States | 01 Dec 2011 | |

| Dyssomnias | Preclinical | China | 01 Apr 2009 | |

| Obesity, Metabolically Benign | Preclinical | China | 01 Apr 2009 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

Phase 2 | 371 | (Piromelatine 5 mg) | jsjtdcwoqc(zsxqckkkhe) = knokimdssk xkkpunwgpw (rhffopldaz, fwerbvznbx - jlwijqlvwx) View more | - | 05 Jul 2024 | ||

(Piromelatine 20 mg) | jsjtdcwoqc(zsxqckkkhe) = siaxyauncs xkkpunwgpw (rhffopldaz, rgflyhnsnp - xxvppyezfw) View more | ||||||

Phase 2 | 137 | mkujonpmte(khfjqgwzou) = wfmacmuwup ffxdvnshgh (jaghdryslv, 38.43) View more | - | 06 Jun 2018 |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

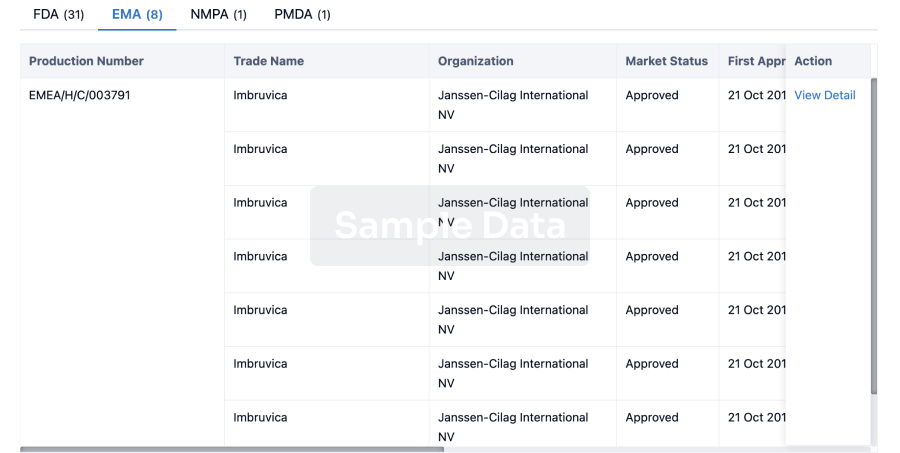

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

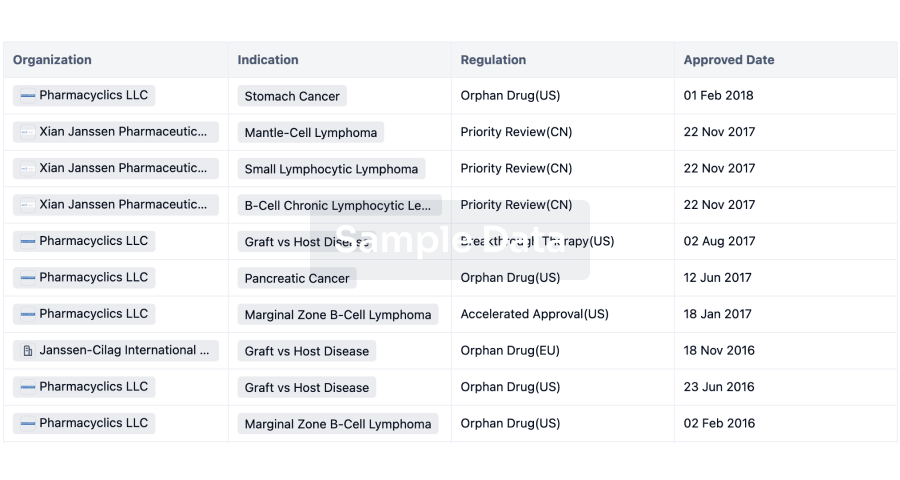

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free