An 80-year-old man with a history of Henoch-Schonlein Purpura at the age of 59 requiring partial jejunal resection, coronary artery disease, CKD, gout, GERD, and prior cholecystectomy was admitted for 2 weeks of guaiac positive watery brown diarrhea and dehydration. Medications included aspirin 81mg daily, clopidogrel, aldactazide, furosemide, hydralazine, isosorbide mononitrate, metoprolol, simvastatin, lansoprazole, allopurinol, trazodone, and tamsulosin. He had switched from citalopram to bupropion two weeks prior. He was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. His abdomen was distended and tympanitic, with normal bowel sounds and tenderness to palpation over the epigastrium and periumbilical area, but no peritoneal signs. Laboratory evaluation revealed creatinine 1.96 mg/dL, WBC 8.8×109/L with 81% neutrophils, c-reactive protein (CRP) 27.2 mg/L. Urinalysis, stool culture, C. diff toxin, ova & parasites, and serum anti-TTG IgA/IgG were negative. Abdominal CT scan and upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies were unremarkable. Colonoscopy revealed a >15cm linear ulcer in the descending colon and mild patchy erythema in the proximal colon (Figure A). Right and left colonic biopsies showed mildly active colitis, with sloughing of the surface epithelium and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (Figure B). He symptomatically improved during his 6-day hospitalization. Following discharge, he was started on balsalazide 750mg po tid and nightly mesalamine enemas for presumed ulcerative colitis.

Figure A

Figure B

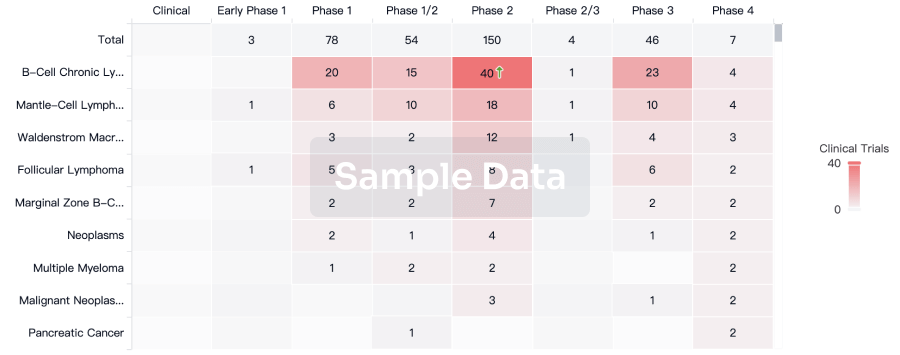

He was readmitted 1 month later with voluminous diarrhea and dehydration. Physical exam, stool microbiology, and repeat abdominal CT scan were identical to his first admission. Laboratory evaluation revealed WBC 11.2×109/L with 86% neutrophils, and CRP 125.5 mg/L. Flexible sigmoidoscopy demonstrated two long linear ulcers in the descending colon with patchy moderate inflammation, submucosal hemorrhages, and shallow ulcerations in the rectum, sigmoid, and descending colon (Figure C). Biopsies revealed collagenous colitis with a markedly thickened subepithelial collagen table (Figures D&E). Re-review of his initial colonoscopic biopsies suggested lymphocytic colitis. He symptomatically improved on methylprednisolone and was transitioned to a prednisone taper.

Figure C

Figure D

Figure E

Further history uncovered that 3 months prior to his initial presentation he switched to one of his present medications from a related medication for insurance reasons, so we discontinued this medication and rapidly tapered the prednisone over 3 weeks. His symptoms resolved completely. Colonoscopy performed 6-7 weeks after steroids were discontinued was normal (Figure F), including normal biopsies from the right and left colon (Figure G).

Figure F

Figure G

Question: What is the most likely cause of his drug-induced microscopic colitis?

Answer to the Clinical Challenges and Images in GI Question: Lansoprazole

Microscopic colitis (MC) is characterized by chronic watery diarrhea. Typically colonoscopy reveals normal-appearing colonic mucosa. Biopsy findings may indicate either lymphocytic colitis (LC), with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (>20 lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells), or collagenous colitis (CC), characterized by a thick subepithelial collagen band (>10 μm). The cause of microscopic colitis is unknown. Medications found to have a high likelihood of causing microscopic colitis include acarbose, aspirin, lansoprazole, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ranitidine, sertraline, ticlopidine, cyclo3fort, and cirkan [1].

The first cases of lansoprazole-induced MC were published in 2001 following a national formulary change from omeprazole to lansoprazole in the VA hospital system. A recently published case series and systematic review of cases of lansoprazole-induced MC found a median time of symptom onset after lansoprazole initiation of 28 days in LC and 60 days in CC [2]. Macroscopic findings such as linear ulcers and submucosal hemorrhages were more common in lansoprazole-induced CC (72.2%) than in lansoprazole-induced LC (6.6%). Other reports of macroscopic findings in microscopic colitis describe associations with NSAIDs, aspirin, lansoprazole, recent antibiotics, or infection [3].

One retrospective case-control study found an adjusted odds ratio of 4.5 (95% CI 2-9.5) for the association between microscopic colitis and PPI use in the preceding 180 days of MC diagnosis [2]. The prevalence of use of individual PPIs in this cohort was omeprazole (40%), esomeprazole (22.8%), pantoprazole (28.6%), rabeprazole (5.7%), and lansoprazole (2.8%).

Management of drug-induced colitis includes removal of the offending agent. In the case of lansoprazole-induced MC, the median time for symptom resolution following drug removal was 7 days for LC, and 14 days for CC [2]. If symptoms do not resolve, treatment can include antidiarrheals, cholestyramine, budesonide, or systemic corticosteroids, depending on the severity of disease.

We suspect our patient had lansoprazole-induced microscopic colitis. It is conceivable that his symptom resolution was due to the corticosteroid course rather than discontinuation of the lansoprazole. However, in > 11 months he has not had symptom relapse, his time course is consistent with other published cases of lansoprazole-induced MC, and other potential etiologies of diarrhea were ruled out. Furthermore, he has remained on aspirin, which is also known to be associated with MC, without relapse.