Request Demo

Last update 22 Nov 2025

Atesidorsen

Last update 22 Nov 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type ASO |

Synonyms Atesidorsen (USAN/INN), Atesidorsen Sodium, ATL-1103 + [1] |

Target |

Action antagonists |

Mechanism GHR antagonists(Growth hormone receptor antagonists) |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization- |

Inactive Organization |

License Organization |

Drug Highest PhasePendingPhase 2 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

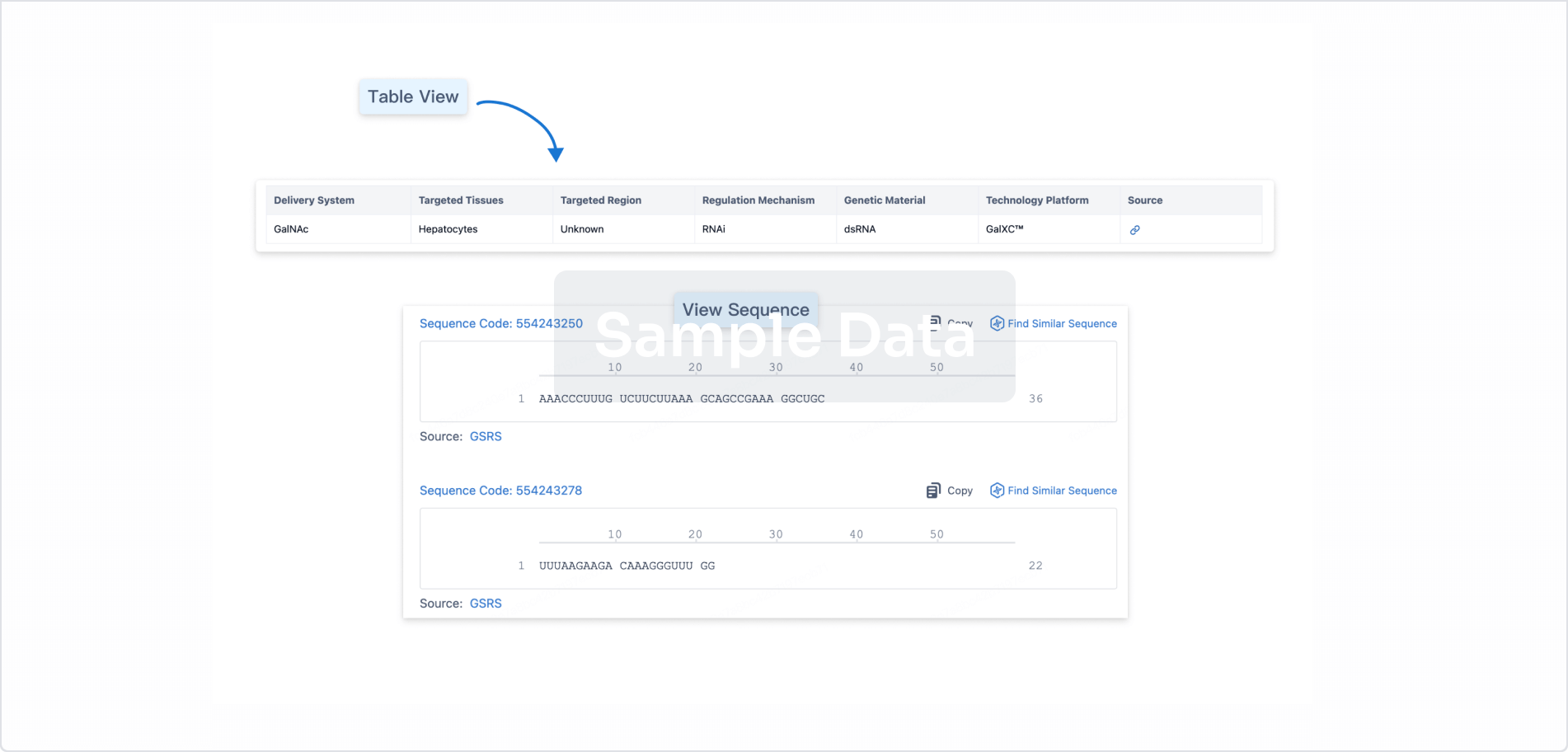

Structure/Sequence

Boost your research with our RNA technology data.

login

or

Sequence Code 524827460

Source: *****

Related

3

Clinical Trials associated with AtesidorsenACTRN12615000289516

A Phase II Open-Label Study of the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of ATL1103 300mg in Adult Patients with Acromegaly.

Start Date07 Aug 2015 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

EUCTR2012-003147-30-ES

A Phase II Randomised, Open-Label, Parallel Group Study of the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of Two Subcutaneous Dosing Regimens of ATL1103 in Adult Patients with Acromegaly.

Start Date29 Jan 2013 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

ACTRN12611000854932

A Randomised, Placebo Controlled, Double-Blind, Single Ascending Dose and Multiple Dose Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Subcutaneous Doses of ATL1103 in Healthy Adult Male Subjects

Start Date28 Jun 2011 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Atesidorsen

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Atesidorsen

Login to view more data

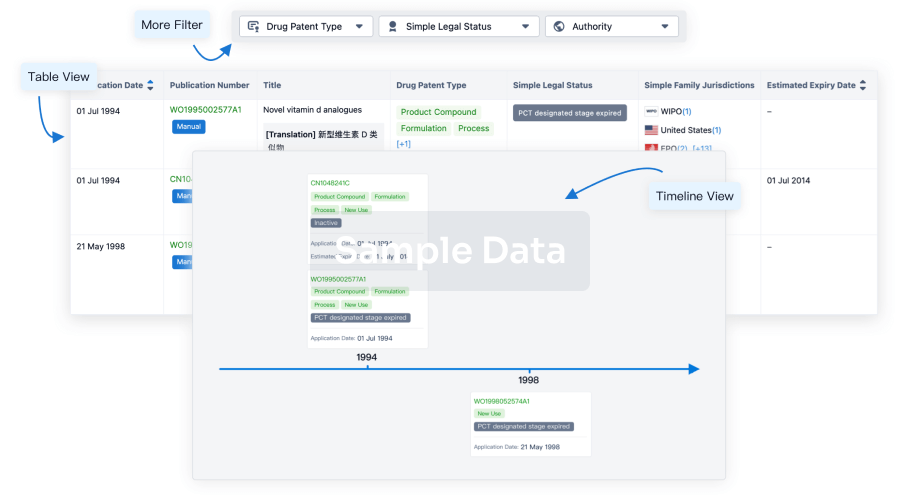

100 Patents (Medical) associated with Atesidorsen

Login to view more data

5

Literatures (Medical) associated with Atesidorsen01 Aug 2018·European journal of endocrinologyQ1 · MEDICINE

A randomised, open-label, parallel group phase 2 study of antisense oligonucleotide therapy in acromegaly

Q1 · MEDICINE

Article

Author: Aylwin, Simon J B ; Rees, Aled ; Ayuk, John ; Drake, William ; Ryder, David ; Atley, Lynne ; Torpy, David J ; Newell-Price, John D C ; Bidlingmaier, Martin ; Fajardo, Carmen ; Aller, Javier ; Brue, Thierry ; Tachas, George ; McCormack, Ann I ; Trainer, Peter J ; Webb, Susan M ; Chanson, Philippe

Objective:

ATL1103 is a second-generation antisense oligomer targeting the human growth hormone (GH) receptor. This phase 2 randomised, open-label, parallel-group study assessed the potential of ATL1103 as a treatment for acromegaly.

Design:

Twenty-six patients with active acromegaly (IGF-I >130% upper limit of normal) were randomised to subcutaneous ATL1103 200 mg either once or twice weekly for 13 weeks and monitored for a further 8-week washout period.

Methods:

The primary efficacy measures were change in IGF-I at week 14, compared to baseline and between cohorts. For secondary endpoints (IGFBP3, acid labile subunit (ALS), GH, growth hormone-binding protein (GHBP)), comparison was between baseline and week 14. Safety was assessed by reported adverse events.

Results and conclusions:

Baseline median IGF-I was 447 and 649 ng/mL in the once- and twice-weekly groups respectively. Compared to baseline, at week 14, twice-weekly ATL1103 resulted in a median fall in IGF-I of 27.8% (P = 0.0002). Between cohort comparison at week 14 demonstrated the median fall in IGF-I to be 25.8% (P = 0.0012) greater with twice-weekly dosing. In the twice-weekly cohort, IGF-I was still declining at week 14, and remained lower at week 21 than at baseline by a median of 18.7% (P = 0.0005). Compared to baseline, by week 14, IGFBP3 and ALS had declined by a median of 8.9% (P = 0.027) and 16.7% (P = 0.017) with twice-weekly ATL1103; GH had increased by a median of 46% at week 14 (P = 0.001). IGFBP3, ALS and GH did not change with weekly ATL1103. GHBP fell by a median of 23.6% and 48.8% in the once- and twice-weekly cohorts (P = 0.027 and P = 0.005) respectively. ATL1103 was well tolerated, although 84.6% of patients experienced mild-to-moderate injection-site reactions. This study provides proof of concept that ATL1103 is able to significantly lower IGF-I in patients with acromegaly.

12 Aug 2016·Expert opinion on pharmacotherapyQ3 · MEDICINE

Current and future medical treatments for patients with acromegaly

Q3 · MEDICINE

Review

Author: Mazziotti, Gherardo ; Giustina, Andrea ; Formenti, Anna Maria ; Frara, Stefano ; Maffezzoni, Filippo

INTRODUCTION:

Acromegaly is a relatively rare condition of growth hormone (GH) excess associated with significant morbidity and, when left untreated, high mortality. Therapy for acromegaly is targeted at decreasing GH and insulin-like growth hormone 1 levels, ameliorating patients' symptoms and decreasing any local compressive effects of the pituitary adenoma. The therapeutic options for acromegaly include surgery, medical therapies (such as dopamine agonists, somatostatin receptor ligands and the GH receptor antagonist pegvisomant) and radiotherapy. However, despite all these treatments option, approximately 50% of patients are not adequately controlled.

AREAS COVERED:

In this paper, the authors discuss: 1) efficacy and safety of current medical therapy 2) the efficacy and safety of the new multireceptor-targeted somatostatin ligand pasireotide 3) medical treatments currently under clinical investigation (oral octreotide, ITF2984, ATL1103), and 4) preliminary data on the use of new injectable and transdermal/transmucosal formulations of octreotide.

EXPERT OPINION:

This expert opinion supports the need for new therapeutic agents and modalities for patients with acromegaly.

01 Jan 2015·EBioMedicineQ1 · MEDICINE

Treatment of Acromegaly: Are We Satisfied With the Current Outcome?

Q1 · MEDICINE

ArticleOA

Author: Roelfsema, Ferdinand

Acromegaly is a rare progressive endocrine disorder, with characteristic symptoms, due to excessive growth hormone (GH) secretion from a pituitary adenoma. Even more rarely, the disease can be caused by hereditary syndromes (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, McCune–Albright syndrome, Carney complex, and familial acromegaly), ectopic tumors or caused by tumor-related excessive GHRH secretion. The reported incidence of acromegaly is 3–4 per one million per year and the prevalence is 60 to 70 per one million, without geographical and sex differences. The disease is likely under-diagnosed (Schneider et al., 2008). Acromegaly leads to multisystem damage, impaired quality of life, even in cured patients, and decreased life expectancy when not properly treated. Since it is reasonable to assume (although not proven) that both the duration of untreated disease and severity of GH excess contribute to the acromegaly-associated abnormalities and organ damage, efforts should be undertaken to detect patients in the population at an early stage, to improve diagnostic procedures and further to develop superior medicines and surgical techniques. Awareness of acromegaly by primary health care doctors as well as by non-endocrine specialists would likely shorten the delay in diagnosis, which is now roughly between 6 and 10 years. When the disease is suspected, the diagnosis is made on increased age-related serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and insufficient suppression of serum GH during glucose loading.

Treatment options are surgery, medical treatment and radiation therapy. The current consensus is that surgery (presently mostly 2-D or 3-D endoscopic surgery, eventually with various forms of neuronavigation) should be performed as an initial treatment by an experienced surgeon in a center with expertise of acromegaly treatment. Normalization of GH and IGF-1 after the first surgical treatment of acromegaly is obtained in 61.2% (range 37–88), based on 32 studies (Roelfsema et al., 2011). Surgery-related pituitary insufficiency is low with 7% and the overall recurrence rate 4.9%, and not related to tumor size. A problem during surgery is the detection of small tumor remnants, especially tumor outgrowth in the cavernous sinus. Careful extended exploration is one of the strategies used. Other groups have introduced the intraoperative use of high resolution MRI with favorable results. Another approach, potentially improving direct results and late outcome in acromegaly, is the application of intraoperative imaging-guided surgery, targeted at the GHRH receptor in acromegaly, as presently in the investigational stage for detection carcinoma remnants during surgery (Chi et al., 2014).

Drugs for medical treatment of acromegaly are dopamine agonists, somatostatin analogs, GH-receptor-blocking agents, GH-receptor synthesis blocking agents, and GH-transcription blocking agents. At present long-acting forms of somatostatin analogs are widely used as GH-suppressive agents. The current clinically used slow-release analogs, octreotide and lanreotide, inhibit GH secretion via the somatostatin receptor subtypes 2 and 5. Although the most important effect of somatostatin analogs is the inhibition of tumor-derived GH and the subsequent fall in circulating liver-derived IGF-I, part of the peripheral effects are caused by the direct inhibition of IGF-I gene transcription via activation after binding to the somatostatin receptor. Multicenter studies have shown that disease activity is controlled in 40–60% of the patients (Roelfsema et al., 2005). Tumor volume reduction of GH adenoma with a weighted mean of 19.4% has been reported to occur in 62% of acromegalic patients during primary therapy with somatostatin analogs (Melmed et al., 2005). A recently marketed drug is pasireotide, which has binding affinities to all somatostatin receptor subtypes, except SST4. The long-acting form of pasireotide requires monthly injections, similar as the other registered long-acting somatostatin analogs. Several phase III clinical trials comparing the efficacy with other long-acting analogs are currently being performed (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00600866, {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT00446082","term_id":"NCT00446082"}}NCT00446082). All somatostatin analogs inhibit insulin secretion, but whether glucose intolerance or frank diabetes mellitus will be more frequent or severe with pasireotide than octreotide or lanreotide is not known yet. A potential very interesting drug (Octreolin®) uses the Transient Permeability Enhancer (TPE) technology. The TPE system causes temporary opening of the tight junctions of the small intestine epithelium, allowing the passage of octreotide (or any other drug) into the blood system. Currently, a multicenter trial is carried out ({"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT01412424","term_id":"NCT01412424"}}NCT01412424). If Octreolin is successful in this relative small competitive market, the treatment of persisting acromegaly is greatly simplified. The use of more effective GH- or IGF-I-suppressive drugs with this carrier system could further improve results.

The role of dopamine agonists is rather limited, and the drugs are mostly used as an adjunct to other forms of medical treatment if IGF-I normalization is not achieved. Cabergoline is the drug of choice and in its present dosage does not lead to cardiac valvular dysfunction. More effective is the GH-receptor blocking drug pegvisomant in normalizing IGF-I, especially when GH levels are not very high, as usually found in previously operated patients. Combining pegvisomant with long-acting somatostatin analogs is an effective way to improve results, permitting dose reduction of the expensive pegvisomant (van der Lely et al., 2012). Patients require careful monitoring of liver functions and the tumor remnant.

Several pharmaceutical companies have developed drugs aimed at blocking the IGF receptor, including GSK 1904529A and ATL 1103, an antisense drug. Although these drugs could be used potentially in acromegaly, they are primarily developed as adjunct drugs in cancer treatment (Tachas et al., 2006, Sabbatini et al., 2009).

A new concept in inhibiting GH secretion is the construction of targeted secretion inhibitors. These engineered proteins incorporate botulinum neurotoxin and a GHRH-receptor binding domain. After binding to the receptor, the complex is internalized in the endosome. Insertion of the translocation domain into the endosomal membrane allows the delivery of endopeptidase into the cell, leading to cleavage of the SNARE proteins (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor). SNARE proteins dock and fuse GH hormone-containing vesicles with the cell surface membrane, allowing subsequent GH secretion. Experimental data in rats have shown that this class of promising drugs is a potent inhibitor of GH secretion, but the present formulations are without GH-suppressive effect in human adenoma in vitro (Somm et al., 2012).

The place of radiation therapy in the treatment of acromegaly is rather limited, and currently is only used when all other options are unsuccessful in normalizing IGF-I. Radiation modalities include fractionated conventional external beam irradiation with a linear accelerator via a three-field or a rotational technique. The total dose is generally 40–50 Gy, and the fractional dose 1.8–2.0 Gy. The time interval required for normalization of GH depends on the initial level. The most frequent side effect is hypopituitarism in up to 50% of the patients after 10 years. The other treatment modality is radiosurgery. This technique is the precise stereotactic delivery of a single high radiation dose to a defined target with a steep dose gradient at the margin. Radiation may be given by the Gamma knife, a linear accelerator (Linac)-based system or proton beams (Minniti et al., 2011). Particularly, proton beam equipment is very expensive, but may be superior to other forms of radiation therapy. Nevertheless, long-term controlled studies comparing results of the different treatment forms are largely lacking.

In summary, there are several possible strategies for improving outcome of treatment of acromegaly. Even if patients are cured by expert surgery, many of them are still suffering from irreversible organ damage. In an ideal world the diagnosis should be made before gross and irreversible abnormalities occur. Awareness of this disease by primary care physicians may lead to earlier and more frequent diagnosis. Further improvement of endoscopic surgery tools with equipment for detection of small tumor remnants after removal of the gross tumor will improve the outcome of surgery. The second generation of somatostatin receptor blocking drugs and the GH-receptor blocking pegvisomant, although rather effective if GH levels are not high, should be replaced my more effective drugs. Several of these new classes of drugs with different action mechanisms are currently under development.

2

News (Medical) associated with Atesidorsen22 Oct 2015

DUBLIN, Ireland and TREVOSE, Pa., Oct. 21, 2015 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Strongbridge Biopharma plc (NASDAQ:SBBP) announced today the closing of its initial U.S. public offering of 2,500,000 ordinary shares at a price to the public of $10.00 per ordinary share for aggregate gross proceeds of $25 million, before deducting the underwriting commission and estimated offering expenses. In connection with the offering, Strongbridge Biopharma has granted to the underwriters a 30-day option to purchase up to an additional 375,000 ordinary shares at the public offering price, less the underwriting discount. Strongbridge Biopharma's ordinary shares are listed on The NASDAQ Global Select Market under the symbol "SBBP".

Stifel acted as the sole book-running manager for the offering. JMP Securities acted as lead manager, and Roth Capital Partners and Arctic Securities acted as co-managers.

A registration statement relating to these securities was declared effective by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on October 15, 2015. The offering is being made only by means of a prospectus. Copies of the final prospectus related to the offering may be obtained from: Stifel, Nicolaus & Company, Incorporated, One Montgomery Street, Suite 3700, San Francisco, CA 94104, Attention: Syndicate, by telephone at (415) 364-2720 or by email at syndprospectus@stifel.com.

This press release shall not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy, nor shall there be any sale of these securities in any state or jurisdiction in which such offer, solicitation or sale would be unlawful prior to registration or qualification under the securities laws of any such state or jurisdiction.

About Strongbridge Biopharma

Strongbridge Biopharma's strategic focus is to build a biopharmaceutical company focused on the development, in-licensing, acquisition and eventual commercialization of complementary product candidates across multiple franchises that target rare diseases. Strongbridge Biopharma's lead product candidate, COR-003 (levoketoconazole), is a cortisol inhibitor that is currently being studied in the global Phase 3 trial for the treatment of endogenous Cushing's syndrome. COR-003 has received orphan designation from both the European Medicines Agency and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Strongbridge Biopharma recently expanded its rare endocrine disease franchise with the completion of transactions for two Phase 2 product candidates: COR-004, a novel second-generation antisense compound, which is in clinical development for the treatment of acromegaly and designed to block the synthesis of growth hormone receptor (GHr), thereby reducing levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in the blood; and COR-005, a next-generation somatostatin analog (SSA) with a unique receptor affinity profile, being investigated for the treatment of acromegaly, with potential additional applications in Cushing's disease and neuroendocrine tumors. Strongbridge Biopharma's intent is to independently commercialize its rare endocrine assets in key global markets. CONTACT: Corporate and Media Relations Elixir Health Public Relations Lindsay Rocco +1 862-596-1304 lrocco@elixirhealthpr.com Investor Relations ICR Inc. Stephanie Carrington +1 646-277-1282 Stephanie.Carrington@icrinc.com USA 900 Northbrook Drive Suite 200 Trevose, PA 19053 Tel. +1 610-254-9200 Fax. +1 215-355-7389

Help employers find you! Check out all the jobs and post your resume.

Acquisition

15 May 2015

May 15, 2015

By

Riley McDermid

, BioSpace.com Breaking News Sr. Editor

Swedish biotech

Cortendo

has made a series of deals for around $140 million to build out its rare disease pipeline, the company said this week, as it seeks to raise $33.2 million through a private placement. Those funds will then be rolled into further development of its portfolio, the company said in a statement.

The company’s chief executive also said

Cortendo

is “actively exploring” other possible partnerships in endocrinology.

Cortendo

said it will pay about $30 million in equity for investigational drug Somatoprim (DG3173) from

Aspireo Pharmaceuticals

. That drug is poised to move into Phase III trials for acromegaly in newly-diagnosed patients and is a next-generation somatostatin analog (SSA). It has also shown some promise at treating neuroendocrine tumors and Cushing’s Syndrome by reducing growth hormone secretion.

“

Cortendo

is dedicated to addressing the needs of the rare disease community, and we are focused on developing novel therapeutic options and resources for rare diseases that will make a difference for patients, their families and physicians.

The opportunity to advance ATL1103, a novel second-generation antisense therapeutic with potential utility in acromegaly, nicely complements COR-003, our existing Phase 3 asset for Cushing’s Syndrome, and builds upon our rare endocrine disease franchise,” said Matthew Pauls, president and chief executive officer of

Cortendo

.

“We are also continuing to actively explore other partnerships in endocrinology as well as other therapeutic areas for rare diseases.”

In addition,

Cortendo

just inked an exclusive licensing agreement with

Antisense Therapeutics Limited

for development and commercialization rights outside of Australia and New Zealand for experiemental drug ATL1103. That clinical-stage second generation antisense drug is designed for endocrinology applications and has shown potential for treating like acromegaly, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, and some forms of cancer, the company said.

Under the terms of the deal

Cortendo

will pay

Antisense

$5 million upfront, with $3 million in cash and $2 million in

Antisense

equity. It will also pony up as much as $105 million in payments tied to achieving development and commercialization milestones, with the potential for royalty payments based upon sales performance.

“This is a significant deal not only for

Antisense Therapeutics

and its shareholders, but also for the Australian biotech industry as a whole,” said

Mark Diamond

,

Antisense

’s CEO and managing director. “We aim to unlock further value from our pipeline, including ATL1102 for MS and other potential indications for ATL1103,” Diamond added.

Cortendo

said it will to raise approximately $33.2 million in a new private placement to help fund the development of the two drugs, ATL1103 and Somatoprim, as well a Phase III drug already in

Cortendo

’s pipeline.

Aspireo

’s primary shareholder

TVM Capital

will purchase $4.25 million of

Cortendo

shares, while new institutional investors will also join in, including

Longwood Capital

and

Granite Point Capital

. Existing investors include

RA Capital

,

New Enterprise Associates

,

Broadfin Capital

and

HealthCap

.

“The addition of two novel, late-stage investigational compounds for the treatment of rare endocrine disorders, DG3173 and ATL1103, coupled with our existing Phase III asset for endogenous Cushing’s Syndrome, COR-003, establishes the cornerstone of

Cortendo

’s rare endocrine disease franchise and demonstrates our commitment to becoming a leader in providing innovative therapeutic options to patients with rare diseases,” Pauls.

Will AbbVie, Genentech’s New Cancer Drug Be a Game Changer?

A promising new blood cancer therapy from

AbbVie

and

Genentech

that snagged headlines in early December for unexpectedly high rates of response in clinical trial patients has now been granted breakthrough status from the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

, the companies said last week. The investigational drug, dubbed venetoclax, is an inhibitor of the B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) protein that is being developed by

Abbvie

in partnership with

Genentech

and

Roche

. BioSpace wants to know what you think this means for the broader market—and could venetoclax be a game changer?

var _polldaddy = [] || _polldaddy; _polldaddy.push( { type: "iframe", auto: "1", domain: "biospace.polldaddy.com/s/", id: "will-abbvie-genentechs-new-cancer-drug-be-a-game-changer", placeholder: "pd_1431536145" } ); (function(d,c,j){if(!document.getElementById(j)){var pd=d.createElement(c),s;pd.id=j;pd.src=(' '==document.location.protocol)?' ':' ';s=document.getElementsByTagName(c)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(pd,s);}}(document,'script','pd-embed'));

Phase 3License out/inBreakthrough TherapyPhase 2

100 Deals associated with Atesidorsen

Login to view more data

External Link

| KEGG | Wiki | ATC | Drug Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| D11161 | - | - | - |

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acromegaly | Phase 2 | Australia | 14 Nov 2012 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

No Data | |||||||

Login to view more data

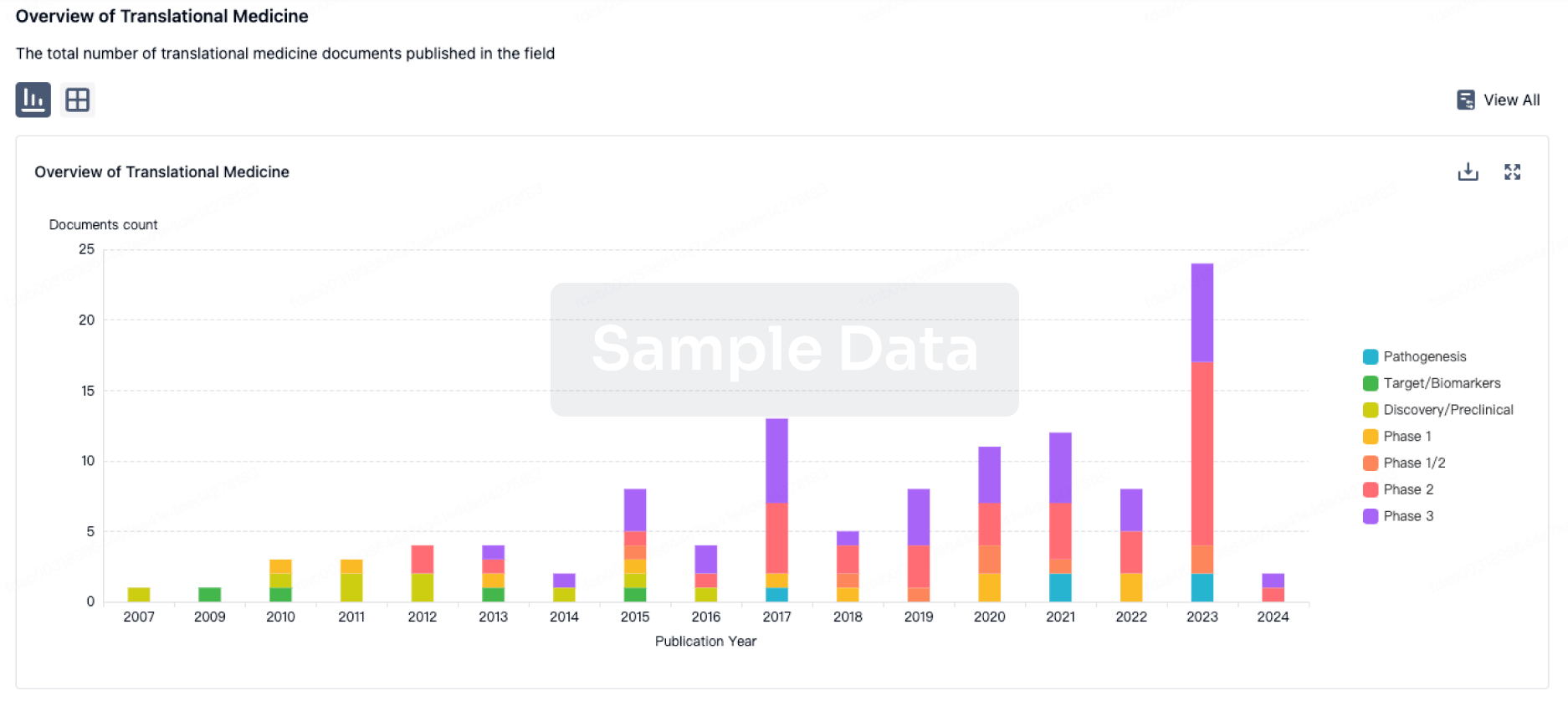

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

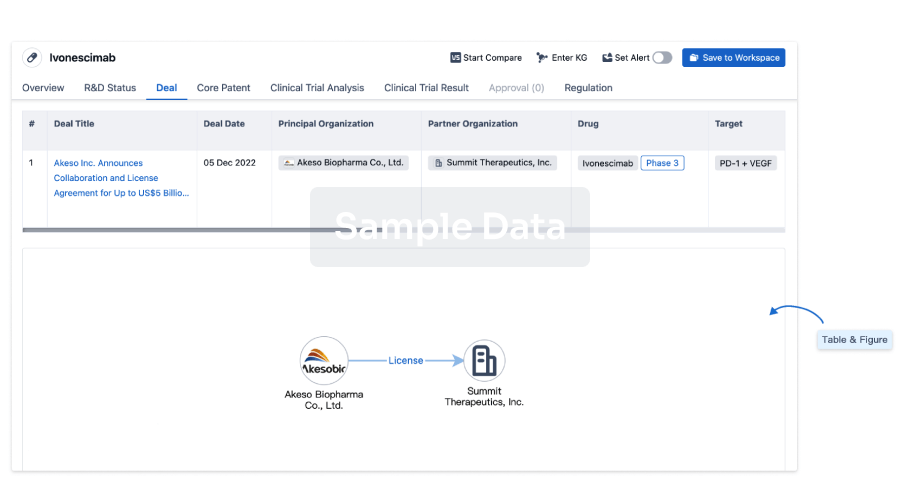

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

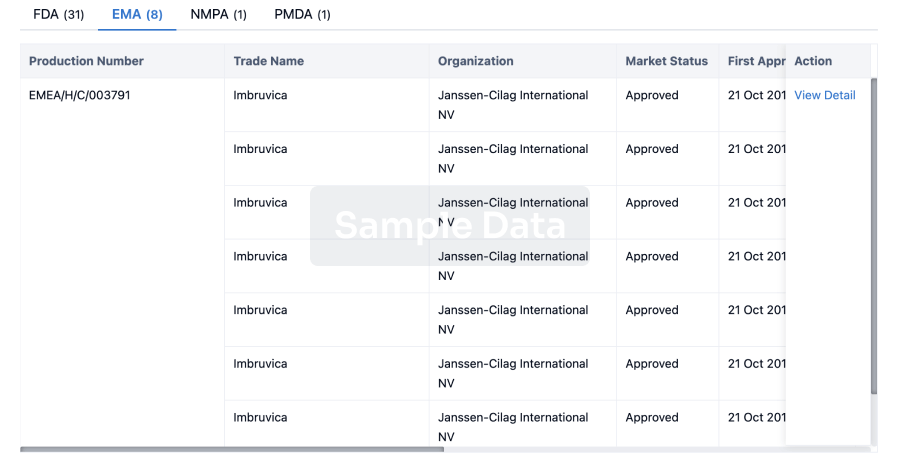

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

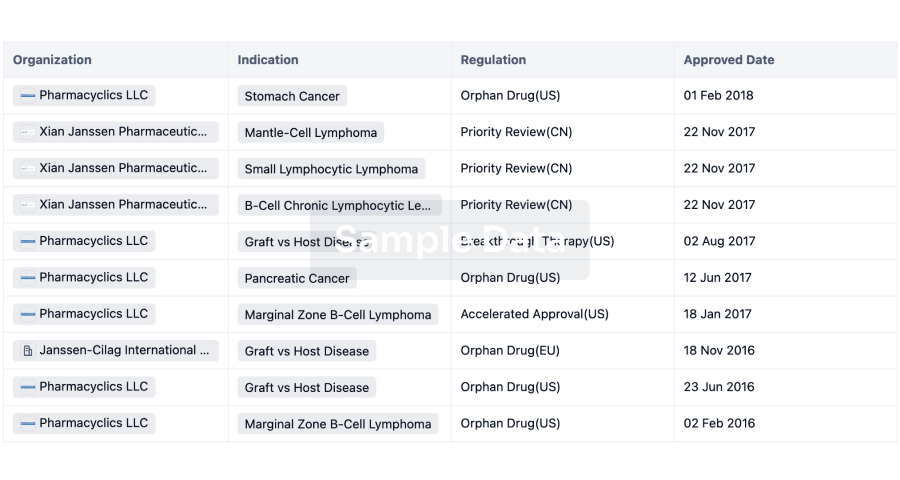

or

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free