Request Demo

Last update 10 Jan 2026

Livoletide

Last update 10 Jan 2026

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Synthetic peptide |

Synonyms UAG-analogue-Alize, Unacylated-analogue-Alize, AZP-01 + [1] |

Target |

Action modulators |

Mechanism ghrelin modulators(Ghrelin modulators) |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization- |

Inactive Organization |

License Organization |

Drug Highest PhaseDiscontinuedPhase 2/3 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC40H63N15O13 |

InChIKeyJXPWLIYXIWGWSA-CLBRJLNISA-N |

CAS Registry1088543-62-7 |

Sequence Code 548715537

Source: *****

External Link

| KEGG | Wiki | ATC | Drug Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - |

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | United States | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | Australia | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | Belgium | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | France | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | Italy | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | Netherlands | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | Spain | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Hyperphagia | Phase 3 | United Kingdom | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Prader-Willi Syndrome | Phase 3 | United States | 25 Mar 2019 | |

| Prader-Willi Syndrome | Phase 3 | Australia | 25 Mar 2019 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

Phase 2/3 | 158 | (Low-Dose Livoletide) | tagannezro(twafjdvdru) = mvxrupgdjn ixqacopuwl (rgwssmlzzn, 7.76) View more | - | 17 Feb 2021 | ||

(High-Dose Livoletide) | tagannezro(twafjdvdru) = dbkkbxujfn ixqacopuwl (rgwssmlzzn, 6.08) View more | ||||||

Phase 2 | 47 | Livoletide (AZP-531) (Obese participants) | hcwnelszoi(cagtcyjfvg) = bkfcgdjajx hfielxrwfg (zbgkspoprg ) View more | Positive | 08 May 2020 | ||

Livoletide (AZP-531) (Non-obese participants) | hcwnelszoi(cagtcyjfvg) = ybdrhncbqr hfielxrwfg (zbgkspoprg ) View more | ||||||

Phase 1/2 | 44 | gchzxqbqiw(uyalzvshaf) = oeduyevrvy wrwfkhtwlf (lkywuwoper ) View more | Positive | 01 Sep 2016 | |||

Placebo | gchzxqbqiw(uyalzvshaf) = aedldleded wrwfkhtwlf (lkywuwoper ) View more |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

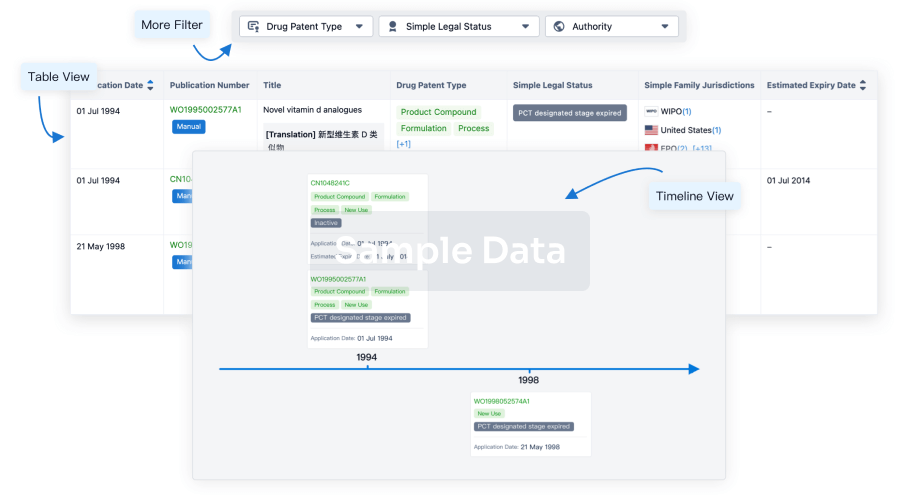

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

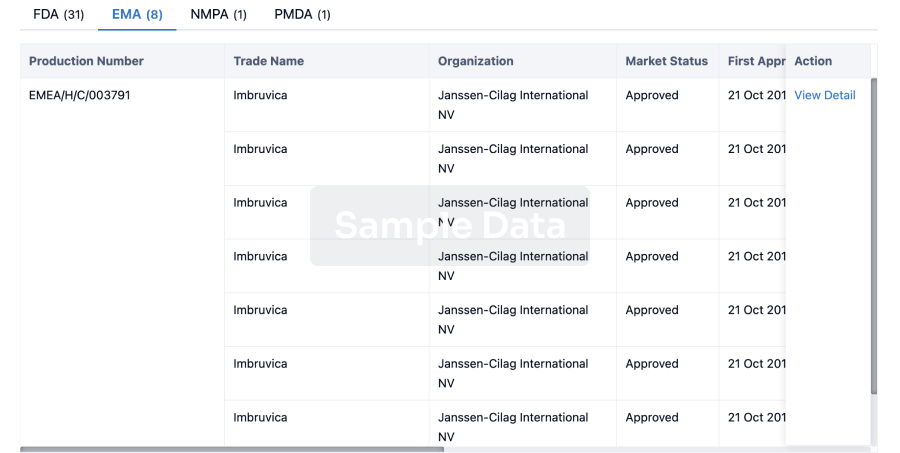

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

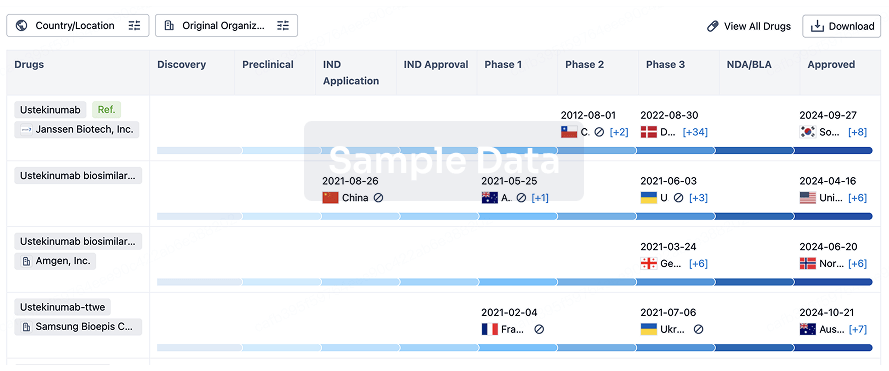

Biosimilar

Competitive landscape of biosimilars in different countries/locations. Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3.

login

or

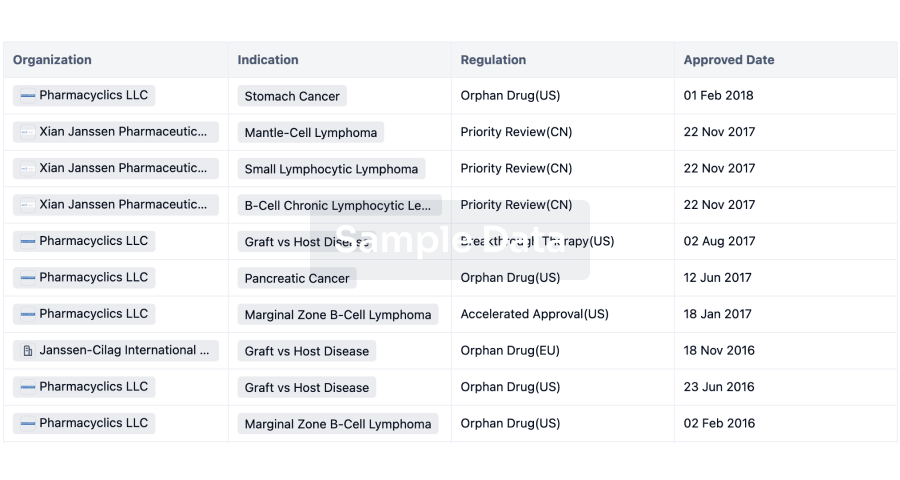

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free