Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Introduction Gordian Biotechnology, Inc. is a therapeutics company that specializes in the development of a screening platform for gene therapy aimed at treating age-related diseases. It was established by Martin Borch Jensena and Francisco LePort in 2014 and is based in San Francisco, CA. |

Tags

Digestive System Disorders

AAV based gene therapy

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| AAV based gene therapy | 1 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| FGF19(Fibroblast growth factor 19) | 1 |

Related

1

Drugs associated with Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.Target |

Mechanism FGF19 gene stimulants |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

100 Clinical Results associated with Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.

Login to view more data

3

News (Medical) associated with Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.26 Apr 2024

$60 Million in Venture Capital Raised to Date from World-Class Longevity, Biotech, and Technology InvestorsUnprecedented Approach Tests Hundreds of Gene Therapies Simultaneously in Individual Animals that are Highly Representative of Human Patients, Including Horses and MonkeysScreen Results Match Preclinical and Clinical Outcomes of Two Age-Related Indications with 80% Accuracy

SAN FRANCISCO, April 26, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Gordian Biotechnology, an in vivo drug discovery and development company, today announced its platform that enables patient predictive, in vivo screening of hundreds of gene targets for FDA-recognized diseases of aging at a scale never before possible.

The company has raised $60 million to date from investors including The Longevity Fund, Arctica Ventures, Athos Service GmbH, Gigafund, Founders Fund, Fifty Years, and former Novartis CEO Thomas Ebeling.

Gordian Biotechnology Gene Therapy Testing Platform

Gordian Biotechnology Scientists Process Tissue From a Mosaic Screening in the Company’s South San Francisco Headquarters

Gordian Biotechnology Gene Therapy Testing Platform

Traditional Drug Discovery Compared to Gordian Biotechnology

Gordian Biotechnology In Vitro vs. In Vivo Gene Therapy Testing

Gordian Biotechnology Single Gene Therapy Screen Results

Gordian's Osteoarthritis (OA) program has screened hundreds of therapies in horses that acquired OA naturally and advanced dozens of therapies into human ex vivo validation studies. The results of these ex vivo studies matched screen predictions with 80% accuracy, and several hits progressed to additional testing and optimization. Gordian presented these findings at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) World Congress last week.

In proof of concept experiments during initial development, Gordian introduced a pooled library of 50 gene therapies into a mouse model of metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). The therapies were evaluated using the company's proprietary in vivo screening platform, which successfully recapitulated 13 out of 16 clinical outcomes for targets where clinical data exists.

Today, Gordian is completing in vivo screens of thousands of novel single and multi-target therapies across four indications in highly representative animal models across multiple species.

"Gordian leverages recent advancements in single-cell sequencing and gene therapy to discover and predict what drugs will be successful in a way that would have been inconceivable just five years ago," said co-founder and CEO Francisco LePort. "Our ultimate goal is to help people wake up every day, more capable than the one before."

The first and only platform of its kind

Screening in vivo lets Gordian run the equivalent of hundreds of preclinical experiments in a matter of months and at a small fraction of the cost of traditional preclinical studies. Thus, enormous amounts of in vivo data are obtained at the beginning of the discovery process in animal models that would otherwise be impractical to use, allowing only the most efficacious therapeutics to move into development and clinical trials.

The Gordian platform consists of three proprietary components working in concert:

Patient Avatars™ are animal models with biology more representative of human patients than those typically used, such as horses for OA and monkeys for MASH. Because few animals are required for screening, Gordian can use large or advanced animal models that would otherwise be impractical for extensive preclinical studies. Often these animal models acquire the disease naturally and therefore have other conditions associated with biological aging, as a human would.

Mosaic Screening™ is pooled in vivo screening that tests hundreds of therapies simultaneously in a single sick animal, the Patient Avatar. The diseased tissue becomes a "mosaic," where different cells receive different barcoded therapies. The therapies are introduced at a low dose, such that each perturbed cell is separated by diseased tissue unperturbed by any treatment, minimizing interactions between treatments. Each of these cells is sequenced, revealing the effect of each therapy in the full diseased in vivo context.

Pythia™ is an analysis methodology that uses artificial intelligence to interpret single-cell data from hundreds of cellular experiments and measure the effect of each therapy in vivo. By analyzing this data alongside existing human pathology data, Gordian determines which therapies are most likely to succeed in preclinical development and clinical trials.

"Our most severe unmet medical needs are the result of aging. This is due to the complexities of the aging body, often involving multiple comorbidities at once, making research and development especially challenging and expensive," said Martin Borch Jensen, Gordian co-founder and chief scientific officer. "Gordian is creating a future in which age-related ailments are treated and cured as effectively as infectious diseases today."

Aging is the ultimate risk factor for humans, the most expensive, yet research is under-funded.

"Age-related diseases are incredibly complex, and a living animal, ideally one that is aged and acquired the disease naturally, is the only experimental system that can capture this complexity," said Laura Deming, a partner at The Longevity Fund and Gordian investor. "Our ability to understand these diseases is bottlenecked by the rate we can run tests in these living systems. Scaling that rate by over 100 fold is really exciting and is a huge leap toward curing age-related disease."

In addition to MASH and OA, Gordian's current focus indications include heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary fibrosis. The platform is capable of discovering therapies for a long list of complex diseases. The company seeks to partner with pharmaceutical companies to develop drugs as well as move therapeutics into the clinic internally.

LePort and Borch Jensen studied and worked in separate scientific fields in different parts of the world before meeting in early 2018 as a result of their shared interest in longevity entrepreneurship. They founded Gordian in October of that year.

Follow Gordian on LinkedIn and X and visit for more information.

Photos and video available at

Media Contact

[email protected]

About Gordian Biotechnology

Founded in 2018 and headquartered in San Francisco, Gordian is an in vivo drug discovery and development company whose mission is to cure age-related diseases. Named for solving intractable problems by changing the rules, the company has developed an innovative in vivo screening platform that tests thousands of gene therapies and predicts clinical outcomes with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency. The Gordian Platform comprises three proprietary components working in concert to drive predictive ability. Mosaic Screening is the Gordian method of pooled in vivo screening, Patient Avatars are animals most representative of humans, and Pythia is an analysis methodology that combines Gordian screening data with existing human data and uses machine learning to maximize predictive power. The company is funded by world-renowned investors including The Longevity Fund, Athos Service GmbH, Gigafund, Founders Fund, and former Novartis CEO Thomas Ebeling. Gordian: Creating Time.

SOURCE Gordian Biotechnology

Gene Therapy

04 Jan 2023

Using the latest technologies --i ncluding both single-nuclear sequencing of mice and human liver tissue and advanced 3D glass imaging of mice to characterize key scar-producing liver cells -- researchers have uncovered novel candidate drug targets for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Using the latest technologies -- including both single-nuclear sequencing of mice and human liver tissue and advanced 3D glass imaging of mice to characterize key scar-producing liver cells -- researchers have uncovered novel candidate drug targets for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The research was led by investigators at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Utilizing these innovative methods, the investigators discovered a network of cell-to-cell communication driving scarring as liver disease advances. The findings, published online on January 4 in Science Translational Medicine, could lead to new treatments.

Characterized by fat in the liver and often associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and elevated blood lipids, NAFLD is a worldwide threat. In the United States, 30 to 40 percent of adults are estimated to be affected, with about 20 percent of these patients having a more advanced stage called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, which is marked by liver inflammation and may progress to advanced scarring (cirrhosis) and liver failure.

NASH is also the fastest-rising cause of liver cancer worldwide. Since advanced stages of NASH are caused by the accumulation of fibrosis or scarring, attempts to block fibrosis are at the center of efforts to treat NASH, yet no drugs are currently approved for this purpose, say the investigators.

As part of the experiments, the researchers performed single-nuclear sequencing in parallel studies of both mouse models of NASH and human liver tissue from nine subjects with NASH and two controls. They identified a shared number of 68 pairs of potential drug targets across the two species. Furthermore, the investigators pursued one of these pairs by testing an existing cancer drug in mice as a proof of concept.

"We aimed to understand the basis of this fibrotic scarring and identify drug targets that could lead to new treatments for advanced NASH by studying hepatic stellate cells, which are the key scar-producing cells in the liver," said senior study author Scott L. Friedman, MD, Irene and Dr. Arthur M. Fishberg Professor of Medicine, Dean for Therapeutic Discovery, and Chief of Liver Diseases at Icahn Mount Sinai. "In combining this new glass liver imaging approach -- an advanced tissue clearing method that enables deep insight -- along with gene expression analysis in individual stellate cells, we have unveiled an entirely new understanding of how these cells generate scarring as NASH advances to late stages."

The researchers discovered that in advanced disease, stellate cells develop a dense network, or meshwork, of interactions among themselves that facilitate these 68 unique interaction pairs not previously identified in this disease.

"We confirmed the importance of one such pair of proteins, NTF3-NTRK3, using a molecule already developed to block NTRK3 in human cancers and repurposed it to establish its potential as a new drug to fight NASH fibrosis," said first author Shuang (Sammi) Wang, PhD, an instructor in the Division of Liver Diseases. "This new understanding of fibrosis development suggests that advanced fibrosis may have a unique repertoire of signals that accelerate scarring, which represent a previously unrecognized set of drug targets."

The researchers hypothesize that the circuitry of how cells communicate with each other evolves as the disease progresses, so some drugs may be more effective earlier and others at more advanced stages. And the same drug may not work for all stages of disease.

The investigators are currently working with Icahn Mount Sinai chemists to further optimize NTRK3 inhibitors for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Next, the investigators plan to functionally screen all candidate interactors in a cell-culture system, followed by testing in preclinical models of liver disease, as they have done for NTRK3. In addition, they hope to extend their efforts to determine if similar interactions among fibrogenic cells underlie fibrosis of other tissues including heart, lung, and kidneys.

The paper is titled "An autocrine signaling circuit in hepatic stellate cells underlies advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis."

Additional co-authors are: Kenneth Li (Icahn Mount Sinai); Eliana Pickholz Li (Icahn Mount Sinai); Ross Dobie (University of Edinburgh, UK); Kylie P. Matchett (University of Edinburgh, UK); Neil C. Henderson (University of Edinburgh, UK); Chris Carrico (Gordian Biotechnology, CA); Ian Driver (Gordian Biotechnology, CA); Martin Borch Jensen (Gordian Biotechnology, CA); Li Chen PharmaNest, Inc., NJ); Mathieu Petitjean (PharmaNest, Inc.,NJ); Dipankar Bhattacharya (Icahn Mount Sinai); Maria I. Fiel (Icahn Mount Sinai); Xiao Liu (University of California); Tatiana Kisseleva (University of California); Uri Alon (Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel); Miri Adler (Yale University School of Medicine, CT); Ruslan Medzhitov (Yale University School of Medicine, CT).

The work was supported, in part, by funds from the National Institutes of Health grant numbers R01DK56621, R01DK128289, TR004419, P30CA196521, R01DK101737, R01DK099205, R01DK111866, R01AA028550, P50AA011999, P30 DK120515, and U01AA029019.

10 Sep 2021

Martin Borch Jensen was

attending

a small conference last year when Patrick Collison, the billionaire CEO of Stripe, got on stage to talk about Covid Fast Grants, the fund he co-launched in April 2020 to help researchers quickly pivot their work to address the pandemic.

Collison, economist Tyler Cowen, and bioengineer Patrick Hsu set up Fast Grants after it became clear that, despite the emerging crisis, many researchers were waiting

months

to get through the NIH’s bureaucratic grant process. They

raised

$50 million and funded trials on repurposed drugs, the development of saliva-based tests, and research on long Covid, among other efforts.

And the trio became

evangelists

for alternative funding models in science.

Jensen, co-founder and CSO of the longevity biotech Gordian Biotechnology and a former postdoc at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, wondered if he could set up the same thing for his own field.

“A lot of the crazy ideas don’t get funding,” Jensen told

Endpoints News.

“There’s all these ideas that people have that could be really important but they either don’t apply or they apply and they don’t get funding.”

A year later, fast grants for aging have become a reality. Teaming with a couple of other prominent members of the insular longevity field — Laura Deming, co-founder of the Longevity Fund, is on the board — Jensen launched Longevity Impetus Grants this week. So far, he’s raised $26 million, which he plans to dole out to academics and non-profits in $10,000 to $500,000 increments.

As often is the case in the longevity field, the funding comes largely from wealthy individuals in the tech world. That includes Juan Benet, CEO of Protocol Labs, and Vitalik Buterin, the 27-year-old co-founder of the cryptocurrency Ethereum. Applications open Monday but Jensen will continue to try to raise more.

Unlike with Covid, there is no burning crisis the grants are trying to address (although Jensen, like many in the longevity field, will talk at length about the crippling burden our rapidly aging world will place on its healthcare systems).

But Jensen and his reviewers, who are anonymous, will try to back ideas they say have been ignored by the traditional funding sources for aging work. And they will try to do so quickly, offering an abbreviated grant application and promising a decision within three weeks of submission. (A typical NIH grant review can involve 10-20 scientists and three separate phases.)

Top funders mostly back only a handful of ideas that have already been proven to extend lives of lab animals, Jensen argued, such as caloric restriction and senescent cells, leaving other hypothesized aging and anti-aging mechanisms under-tested. For example, he said, research on the role the extracellular matrix — all the proteins, metabolites and other detritus floating outside the cell — plays in aging has gotten little attention.

In one major case, these entities are restricted in what they’re even allowed to back. National Institutes on Aging, one of the key sources for funding for academic longevity research, legally has to give a significant percentage of its grants to Alzheimer’s work, Deming noted.

“Often scientists have to twist their ideas into a pretzel to fit what funders want,” she said in an email.

Impetus, in theory, will be more open. The new effort comes amid a new surge of funding into longevity research. Google subsidiary Calico and AbbVie

pledged another

$1 billion for their anti-aging and cancer work. And over the past year, high-profile figures from Silicon Valley have raised hundreds of millions of dollars and

recruited

high-profile professors and biotech executives for Altos Labs, a company focused on reprogramming cells to make them “younger.”

On the government side, President Biden has proposed a new institute, called $6.5 billion

ARPA-H,

that would fund high-risk medical research. Much of it would focus on age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

The grants initiative has been met with support from other prominent researchers in the anti-aging field. Harvard biologist David Sinclair, who

showed

he could rejuvenate neurons and restore vision in mice last year, said in an email the grants would help the longevity field continue to accelerate at its “increasingly fast pace.”

Paul Robbins, a biochemist at the University of Minnesota, said the aging field has long needed a funding mechanism for risky research that isn’t driven by a single hypothesis. He hopes Impetus will fund research on cellular reprogramming or efforts to analyzing centenarians and supercentenarians (people over 110) for genetic clues that turn into drug targets.

“However, like any granting agency, the process depends upon the qualifications and biases of the review group,” he said in an email. “Will be interesting to see what types of grants are funded initially.”

Jensen notes that many of the key findings in longevity, including reprogramming and epigenetic “clocks” to compute a person’s age and disease risk, were done without grant money.

He also noted that replication receives little backing because it’s viewed as less glamorous or novel than original studies. He hopes to back studies that determine whether one of the many things scientists have learned extend mouse or worm life actually work in other animals.

Both Jensen and Robbins said they’d like to see work on a biomarker for aging, long one of the holy grails of aging research.

Because a trial directly testing whether a molecule actually extended healthy people’s lives would take far too long, the future of drug development for aging will depend on whether a scientist or a company can prove that some protein or DNA mark correlates directly with enhanced longevity.

Companies could then simply prove their drug significantly changed that marker, in the same way, cardiovascular biotechs can win an approval based on lower cholesterol, rather than waiting to see if their molecule stops heart attacks.

Research in the field is still early, though, making it an unattractive candidate to many funders. But a breakthrough could get the ball rolling.

“Oftentimes it’s like, ‘No, I don’t believe it until someone does it,” Jensen said, describing the NIH’s attitude. With the new grants, “you can do it and then shove it in people’s faces.”

The article has been updated to correct the spelling of Patrick Collison.

100 Deals associated with Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Gordian Biotechnology, Inc.

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 09 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Preclinical

1

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

AAV8-FGF19 Variant M70 (Gordian Biotechnology) ( FGF19 ) | Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

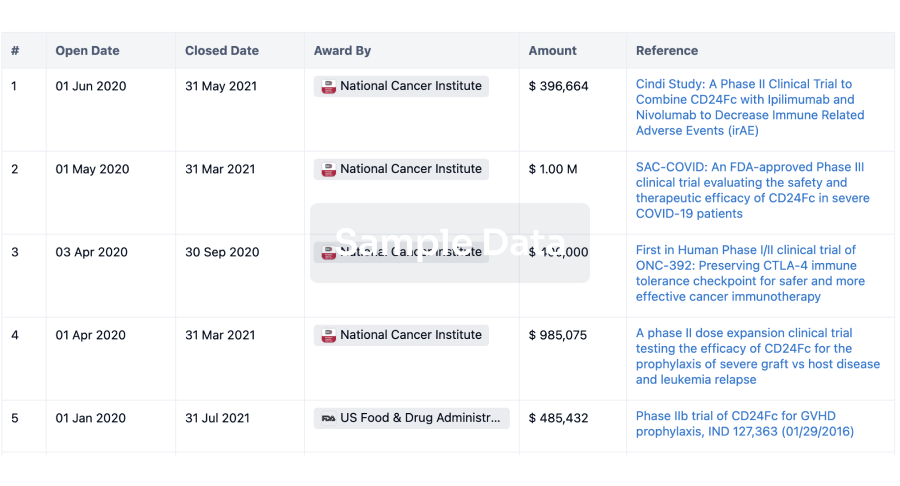

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free