Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Tags

Nervous System Diseases

Immune System Diseases

Infectious Diseases

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Immune System Diseases | 1 |

| Infectious Diseases | 1 |

| Nervous System Diseases | 1 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 1 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| CCR5 x T-type calcium channel | 1 |

Related

1

Drugs associated with Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.Mechanism CCR5 antagonists [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

100 Clinical Results associated with Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

7

News (Medical) associated with Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.05 Jan 2024

Improvement above baseline in cognition and global function is referred to as symptom relief in Alzheimer’s disease. Credits: STEKLO/Shutterstock.com

AmyriAD Therapeutics is looking to evaluate its lead Alzheimer’s disease small molecule candidate AD-101 in three upcoming Phase III studies, CEO Sharon Rogers, PhD, told

Pharmaceutical Technology

.

The Los Angeles, California-based company aims to expand the patient population for its treatment by designing the clinical trials to include patients with mild to severe Alzheimer’s instead of mild to moderate or moderate to severe disease, explains Rogers. Evaluating patients at the highest end of the mild disease group is “very tough” while measuring drug effects because even though evaluation scales like the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and others, can detect deficiencies, they are not sensitive enough to quantify them, she elaborates.

Of the Phase III studies, two—a US trial and another in Europe and Southeast Asia regions— will be designed as adequate and well-controlled (AWC) studies for safety and efficacy that will enrol 500 patients each. Patients in the trials will be enrolled into two equal arms and administered treatment over a 24-week period. Patients on one arm will receive a single dose of the AD-101/Aricept (donepezil) combination treatment while the other group will be given a placebo/Aricept combination.

AD-101 is a once-daily low-voltage-gated T-type calcium channel modulator that increases the release of endogenous acetylcholine. The AD-101/Aricept combination is designed to promote the release of neurotransmitter acetylcholine and preserve it. As per the data from the randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled Phase II proof-of-concept study shared by the company at the 2022 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference, there was additive efficacy in symptom relief when AD-101 was added to a 10 mg daily dose of Aricept.

The Phase III endpoints must demonstrate that a drug improves cognition, a core symptom of the disease, and this should be done using the ADAS-Cog scale, said Rogers. ADAS-Cog is “the gold standard tool” for cognition as it evaluates every category of cognition unlike other tools which are slanted toward language deficits and not as robust at measuring other cognitive domains, she adds.

Another important Phase III endpoint is the independent global function evaluated using AGS-CGIC, which was used in the company’s positive Phase II study and will be used in the upcoming Phase III trials too, said Rogers. AmyriAD will likely use clinical dementia rating (CDR) or the CDR SOB evaluation measures as secondary global endpoints.

Patients must have measurable dementia for diagnosis and inclusion in a clinical trial, said Rogers. As such, AmyriAD will use an MMSE score of 10–22 to include patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer’s disease. Patients in this range are functional enough to provide consent and cooperate with the study, which reduces operational complications of a study, Rogers adds.

The US trial is slotted to commence in Q3 2024, and the Europe and Southeast Asia trials are tentatively planned for Q1 2025, said Rogers. Once patients complete participation in the AWC studies, an open label Phase III extension study will be pursued to characterise long term safety and efficacy of the treatment, said Rogers.

Phase 2Phase 3

29 Nov 2022

The Company's lead drug candidate, AD101, is a small molecule under development for the treatment of Alzheimer's Disease

AD101 is set to enter Phase 3 clinical trials in 2023

LOS ANGELES, Nov. 29, 2022 /PRNewswire/ -- AmyriAD Therapeutics (AmyriAD) a privately held, late clinical-stage pharmaceutical development company focused on advancing therapies for Alzheimer's disease (AD), today announced that it will present data on their lead candidate AD101 at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease Conference (CTAD) on November 29 – December 2 in San Francisco, CA. All abstracts will be published in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease (JPAD).

"Throughout the past two decades, an intense focus has been on modifying the progression of Alzheimer's disease, with the hope of ultimately being able to prevent or cure the disease. Less attention has been given to developing therapies for effective management of the core symptoms of the disease, which are loss of independent function and declining cognition," said Sharon L. Rogers, Ph.D., Chief Executive Officer at AmyriAD. "AmyriAD is one of the few companies developing drugs for core symptom management. Our entire team is committed to improving AD symptoms and returning a sense of agency to patients."

The Company, which emerged from stealth mode only last year during the 14th CTAD Conference, is developing AD101, a first-in-class small molecule that modulates calcium influx into the presynaptic neuron, enhancing release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. This action upregulates neurotransmission and improves learning and memory in animal models.

In randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials, AD101 has been administered as an add-on to stable donepezil (Aricept®) therapy. Donepezil is an inhibitor of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase and protects acetylcholine from degradation after it is released into the synapse. AmyriAD's molecule, when given in conjunction with donepezil, has demonstrated promising evidence of additive improvement of cognition and global function in AD patients (NCT00842816 and NCT00842673).

"During CTAD, we will present clinical and preclinical data that clearly support the advancement of our lead candidate," commented Jan Burmeister, M.D., Medical Director at AmyriAD. "The team is now gearing up to launch our Phase 3 clinical trial program in the first half of 2023. These trials will include patients across a broad range of disease severity reflecting real-life clinical practice."

Details about the presentations follow below. The posters will also be available in the Science section of the AmyriAD website today from 8:30 am EST.

Poster Presentation Theme: New Therapies and Clinical Trials

Poster P030: "AD101-the clinical pro a new, first-in-class treatment for Alzheimer's Disease"

• Presenter: Jan Burmeister, M.D., Medical Director at AmyriAD Therapeutics

• Details: Tuesday, November 29 at 4 pm - Wednesday, November 30 at 6 pm PT, onsite

Poster Presentation Theme: Animal Models and Clinical Trials

Poster P189: "T-type calcium channel modulator AD101 improves cognitive function in animal models of memory and learning impairment and provides a rationale for the potential clinical use of AD101 in the symptomatic treatment of Alzheimer's disease"

• Presenter: Jan Burmeister, M.D., Medical Director at AmyriAD Therapeutics

• Details: Friday, December 2, 8 am – 5 pm PT, onsite

Poster P190: "Effects of T-type calcium channel modulator AD101 on the accumulation of Beta Amyloid, Tau and polyubiquitinated proteins in animal models of Alzheimer's Disease"

• Presenter: Jan Burmeister, M.D., Medical Director at AmyriAD Therapeutics

• Details: Friday, December 2, 8 am – 5 pm PT, onsite

About AD101

AmyriAD's lead candidate for Alzheimer's disease (AD), AD101, is a small synthetic molecule that modulates the activity of specific T-type calcium channels to promote the release of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, in the brain. AD101 currently is being developed to work in concert with a stable regimen of donepezil (Aricept®), the global standard of care for AD since 1996. When administered in combination with donepezil, AD101 was well-tolerated and demonstrated additive improvement over that of donepezil alone in tests of global function and cognition in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 clinical trial in patients with mild to moderate AD.

About AmyriAD Therapeutics

AmyriAD is a private late-clinical-stage pharmaceutical company focused on developing innovative treatments for AD that improve cognition and global function, deficits of which represent the core symptoms of the disease. The Company is led by the development strategist who introduced donepezil which has been the standard of care for AD for more than 25 years.

For more information, please visit and follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

AmyriAD Therapeutics Media Contact:

Erica Fiorini, Ph.D.,

Russo Partners, LLC

Erica.Fiorini@russopartnersllc.com

+1 (914) 310-8172

Phase 2Phase 3Clinical Result

06 Oct 2022

simonkr_Getty Images

While Biogen and Eisai’s recent lecanemab data breathed new life into the anti-amyloid approach, experts say combination therapies will likely play a significant role in treating Alzheimer’s disease.

While promising data from Biogen and Eisai’s lecanemab breathed new life into the anti-amyloid approach last week, Alzheimer’s disease is complex enough that combination therapies will likely play a significant role in future symptomatic treatments.

A combination of medications has proven effective in treating multiple diseases, such as cancer and diabetes. Could the same be true for AD?

Sharon Rogers, Ph.D., chief executive officer of AmyriAD Therapeutics, believes treatments targeting the multiple symptoms of the disease will provide a benefit for patients receiving the standard-of-care treatment Aricept (donepezil).

Last week, AmyriAD hosted a virtual conference highlighting the need for combination therapies.

Rogers explained that for the past 15 years, the primary focus in AD has been on disease modification strategies. While this has expanded the understanding of the disease, Rogers said addressing the core symptoms of AD, such as cognition and core function, is a critical unmet need.

“We’re at the point now that we’re going to look at this with the complexity it deserves… addressing more than one target via combination therapy may provide more successful symptom management,” Rogers said during the panel. “We must do a better job of addressing symptom management, meaning introducing new treatments to improve patient cognition and function.”

Noted AD researcher Serge Gauthier, former director of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Research Unit of the McGill Center for Studies in Aging and Douglas Research Centre in Montreal, argued for this kind of approach.

“We should combine symptomatic drugs if there is a rationale and it’s safe… I will argue that combination therapy for symptom control is the way to go,” Gauthier said during the conference.

Noting the effectiveness in the aforementioned therapeutic areas, Gauthier said he believes a combination approach is also a potentially useful strategy in treating AD. Drugs such as donepezil can be paired with 5-HT receptor antagonists or MAO-B inhibitors and anticonvulsants to treat symptoms of the disease, he noted.

Beyond Anti-Amyloid

Gauthier pointed to the current emphasis on amyloid reduction using individual drugs such as monoclonal antibodies. He said that approach is showing little benefit. There was some hope sparked by

Biogen

’s Aduhelm,

approved

last year based on data that was considered controversial. The approval marked the first for AD in nearly two decades.

Despite the approval, Aduhelm ran into multiple issues, including safety concerns following

reported deaths

of some patients who were taking the medication. During clinical studies, Aduhelm was linked to cases of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA-E), also known as cerebral edema. This was included on the drug’s warning label.

Those concerns though were enough for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to

limit coverage of Aduhelm

to patients who are participating in clinical trials. Earlier this year, the CMS extended that limitation to all monoclonal antibodies used to treat AD.

Lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody,

showed the slowing of disease progression

, including a slowing of loss of memory and thinking skills, Gauthier noted.

The companies called the data “highly statistically significant” and it could bolster potential approval. In July, the FDA

accepted the Biologics License Application

for lecanemab under the accelerated approval pathway and granted Priority Review.

Following the Sept. 28 announcement, Howard Fillit, M.D., co-founder and chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, expressed excitement about the data but added there is still a need for next-generation approaches focused on other, non-amyloid Alzheimer’s targets.

At the AmyriAD conference, Fillit reiterated that statement.

“We’re seeing a little bit of success in the anti-amyloid group but we have to go beyond that,” Fillit said. He added that the successes seen with lecanemab seem incremental and modest when it comes to slowing the delay of disease-related decline.

“Lecanemab is showing hints of efficacy in the amyloid approach but we still need to treat the symptoms,” he said.

Fillit noted that aging is the leading risk factor for AD. With aging comes numerous risk factors that increase the risk of disease, including heart disease, diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure and high cholesterol, he said.

“To effectively conquer Alzheimer’s, we need to develop a unifying approach that targets a multifactorial disease,” Fillit said. “We need drugs that have multiple mechanisms of action and multiple combination therapy approaches. Inflammation has become a leading therapeutic strategy. We need to figure out how to slow down neuro-inflammation.”

For the first time, nearly three-quarters of the experimental treatments for AD are not targeting amyloid plaque nor tau tangles, Fillit noted. With lessons learned from the amyloid-targeted failures, he said researchers are shifting their targets toward these other related areas.

Repurposing Drugs

One way to speed up development of potential treatments is by repurposing older medications. If drugs share a pathway with approaches to the symptoms, repurposing a drug can be worthwhile, Fillit said. Because these older drugs are well-known, it could speed the clinical process and potentially bring a treatment to patients more quickly.

Fillit pointed to promising effects on cognitive decline and other disease hallmarks following treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. GLP-1 agonists are glucose-lowering medications typically used to treat type 2 diabetes, obesity and for cardiovascular risk reduction. There is speculation that AD is related to blood glucose levels.

Novo Nordisk

initiated a Phase III trial

in 2020 assessing its GLP-1 agonist Victoza (semaglutide) in AD. Data has shown the drug’s ability to lower neuroinflammation, which impacts cognition and memory function. The study is expected to be completed in 2024, according to Clinicaltrials.gov. Fillit said researchers will “learn a lot from this strategy.”

Combining with a Tried and True Approach

Donepezil, a cholinesterase inhibitor that has been a standard-of-care treatment for mild- to moderate AD patients for a quarter century, has the best evidence of providing a symptomatic benefit for Alzheimer’s patients – for a while, at least, Gauthier said. It is the type of drug that can benefit from add-on medications, he noted.

Rogers pointed to her company’s lead candidate AD101, an investigational, Phase III-ready therapeutic that demonstrated increased release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The late-stage trial will investigate the potential of AD101 to demonstrate an improvement in cognition and global function through neuroselective T-type calcium channels.

While AD101 increases acetylcholine release, donepezil preserves acetylcholine from breaking down, Rogers said. If you can increase acetylcholine, there should be significant benefits, such as improved cognition.

For Fillit, it is an exciting time in Alzheimer’s research.

“We’re moving to a world of precision medicine like we have in cancer and other chronic diseases of aging,” he said. “I think our aging biology strategy will lead to a lot of benefit and I expect we’re going to have a whole host of drugs in combination therapy. We’re going to have to figure out how to do combination trials better because that’s the next frontier of clinical trials.”

Phase 3Drug ApprovalPriority Review

100 Deals associated with Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Amyriad Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

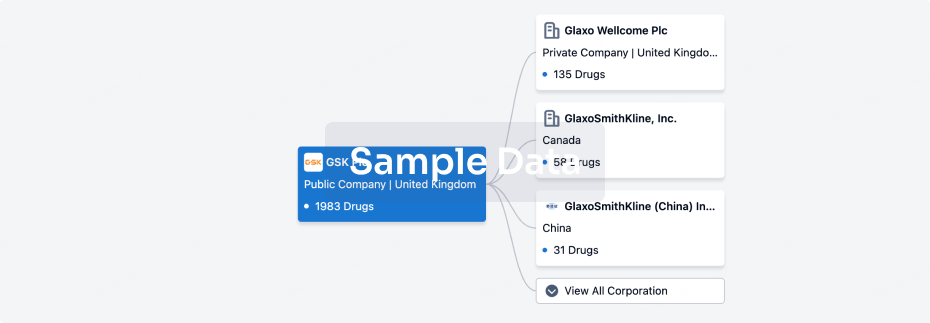

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 12 Mar 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Phase 2 Clinical

1

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

AD-101 ( CCR5 x T-type calcium channel ) | Alzheimer Disease More | Phase 2 |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

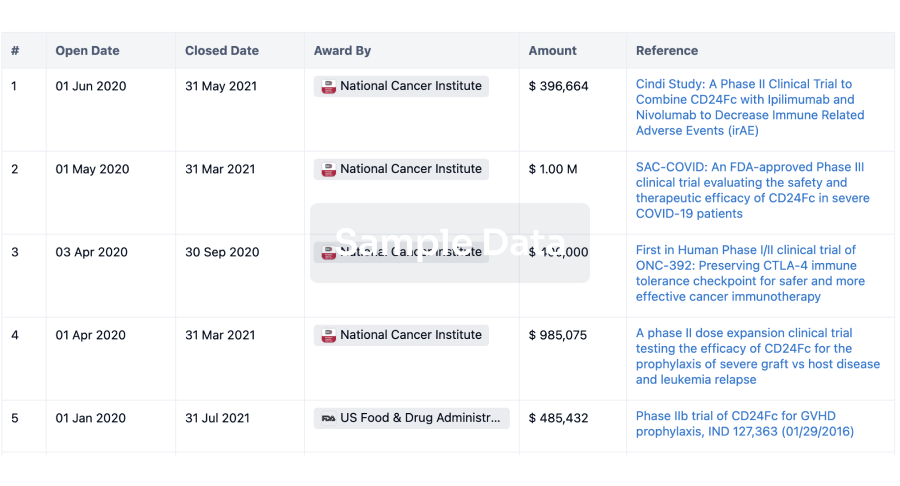

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free