Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

University of California, Berkeley

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Tags

Neoplasms

Cardiovascular Diseases

Infectious Diseases

Small molecule drug

Degradable Molecular Glue

Molecular glue

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 4 |

| Degradable Molecular Glue | 4 |

| Molecular glue | 3 |

| AAV based gene therapy | 1 |

Related

12

Drugs associated with University of California, BerkeleyTarget- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org.- |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism ABCA1 stimulants |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseEarly Phase 1 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Mechanism CDK11B inhibitors [+2] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

214

Clinical Trials associated with University of California, BerkeleyNCT06558422

Human Models of Selective Insulin Resistance: Pancreatic Clamp

This is a single-center, prospective, randomized, controlled (crossover) clinical study designed to investigate the impact of lowering insulin levels on hepatic glucose production (HGP) vs de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in people with insulin resistance. The investigators will recruit participants with a history of overweight/obesity and evidence of insulin resistance (i.e., fasting hyperinsulinemia plus prediabetes and/or impaired fasting glucose and/or Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance [HOMA-IR] score >=2.73), and with evidence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Participants will undergo two pancreatic clamp procedures -- one in which serum insulin levels are maintained near hyperinsulinemic baseline (Maintenance Hyperinsulinemia or "MH" Protocol) and the other in which serum insulin levels are lowered by 50% (Reduction toward Euinsulinemia or "RE" Protocol). In both clamps the investigators will use stable-isotope tracers to monitor hepatic glucose and triglyceride metabolism. The primary outcome will be the impact of steady-state clamp insulinemia on HGP vs DNL.

Start Date01 Jun 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator  Columbia University Columbia University [+2] |

NCT06183281

Integrating Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Pain With Inclusion, Respect, and Equity (INSPIRE): Tailored Digital Tools, Telehealth Coaching, and Primary Care Coordination

INSPIRE creates a trilingual mobile app and telehealth coaching program to promote non-pharmacologic strategies for pain management with Black, Chinese, and Latinx communities in the San Francisco Bay Area. Years 1-2 will develop the app and test it with a brief single arm pilot starting in Nov 2023. A full two arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) will being in early 2025 with changes in PEG scores as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes include Helping to End Addiction Longterm (HEAL) common data elements.

Start Date15 Apr 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06639477

Multi-site Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Efficacy of Behavioral Approaches to Improve Mood and Sleep in Adults

This is a multi-site randomized control trial involving people age 55+ years who have current depression symptoms plus another suicide risk indicator (either current suicidal ideation or a past history of attempt). Our goal is evaluate which of two different approaches works best to improve things like trouble sleeping, bad moods, and any suicidality.

Participants will complete diagnostic interviews, self-report scales, and wear an actigraphy device for the 8 weeks starting at the baseline visit.

Participants will complete diagnostic interviews, self-report scales, and wear an actigraphy device for the 8 weeks starting at the baseline visit.

Start Date01 Apr 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with University of California, Berkeley

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with University of California, Berkeley

Login to view more data

717,419

Literatures (Medical) associated with University of California, Berkeley01 Jan 2026·Neural Regeneration Research

Neuroserpin alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by suppressing ischemia-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress

Author: Shi, Qiaoyun ; Zhang, Shiqing ; Liao, Yumei ; Huang, Zijian ; Peng, Yinghui ; Fukuzaki, Yumi ; Molnár, Zoltán ; Liu, Wei ; Zhang, Xiao-Qi ; Zhang, Xiaoshen ; Guo, Lingling ; Adorján, István ; Ma, Nan ; Zhang, Qinghua ; Shi, Lei ; Kawashita, Eri ; Zhong, Peiyun ; Liu, Peng

31 Dec 2025·Autophagy Reports

Image-based temporal profiling of autophagy-related phenotypes

Author: Adia, Neil Alvin B. ; Beesabathuni, Nitin Sai ; Shah, Priya S. ; Thilakaratne, Eshan ; Gangaraju, Ritika

31 Dec 2025·Global Public Health

Grounding global health in care: connecting decoloniality and migration through racialization

Article

Author: Mehran, Nassim ; Vonk, Levi ; Jaeger, Margret ; Goronga, Tinashe ; Strohmeier, Hannah ; Kluge, Ulrike ; Holmes, Seth M. ; Mair, Lucia ; Pape, Jillian ; Plummer, Jaleel ; Frankfurter, Raphael ; Probst, Ursula ; Dilger, Hansjörg ; Greiwe, Vivien-Lee ; Geeraert, Jérémy

559

News (Medical) associated with University of California, Berkeley05 May 2025

MB-111 is a potential first-in-class in vivo ultracompact CRISPR therapy for Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome and Severe Hypertriglyceridemia

Dr. Brown brings deep expertise in nucleic acid drug development as Mammoth advances its lead program, MB-111, to IND-enabling stage and continues to build a leading company in genetic medicines

BRISBANE, CA, USA I May 05, 2025 I

Mammoth Biosciences, Inc.

, a biotechnology company harnessing its proprietary next-generation CRISPR gene editing platform to create potential one-time curative therapies, today announced the nomination of its first clinical development candidate, MB-111, and the appointment of biotechnology industry veteran, Bob D. Brown, Ph.D., to its Board of Directors.

MB-111 utilizes CasPhi — an ultracompact CRISPR in vivo gene editing system that is less than half the size of first-generation, Cas9-based systems — encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle for delivery to the liver after IV administration.

Share

MB-111 utilizes CasPhi — an ultracompact CRISPR

in vivo

gene editing system that is less than half the size of first-generation, Cas9-based systems — encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle for delivery to the liver after IV administration. MB-111 has the potential to be a first-in-class, one-time treatment for patients with very high triglycerides including familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) and severe hypertriglyceridemia (SHTG).

MB-111 is designed to permanently disrupt the expression of the APOC3 gene in the liver, and thus to reduce expression of ApoC-III protein. ApoC-III is a critical driver of lipid metabolism and disrupting its production has been shown to reduce plasma triglycerides in patients with pathologically elevated levels, including those with FCS and SHTG. These patients suffer from recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, leading to frequent hospitalizations, as well as an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Mammoth Biosciences is on track to initiate IND-enabling studies this year.

“The nomination of our lead program as a development candidate is a major milestone for Mammoth and the gene editing field, as well as the first proof point of the therapeutic potential of our novel ultracompact CRISPR systems and gene editing technologies,” said Trevor Martin, Ph.D., co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of Mammoth Biosciences. “The preclinical data on MB-111 is compelling, and we’re excited about its potential to be a first-in-class genetic cure for debilitating diseases such as FCS and SHTG. We believe Dr. Brown’s extensive drug discovery and development experience, and track record of building leading companies in siRNA and antisense oligonucleotide therapeutics across rare and chronic diseases will be invaluable to our goal of increasing the number of patients who can derive benefit from Mammoth Biosciences’ genetic medicines.”

Dr. Bob D. Brown brings over 30 years of experience in multidisciplinary biotechnology research and drug development, including in the US and ex-US jurisdictions. Most recently, Dr. Brown served as Chief Scientific Officer and Executive Vice President of R&D at Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, an RNAi-focused therapeutics company that was acquired by Novo Nordisk. At Novo, he served as President and Head of the Dicerna Transformation Research Unit and SVP. During his time at Dicerna, he led the discovery and early clinical development of numerous genetic medicines, including nedosiran for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria, RG6346 for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B, belcesiran for the treatment of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and several other drug candidates now in the clinical development pipelines of large pharmaceutical companies.

Prior to Dicerna, Dr. Brown held various positions at Genta, a clinical-stage antisense oligonucleotide therapeutics company, most recently as its Vice President of Research and Technology. Previously, he was a co-founder and Vice President of R&D of Oasis Biosciences, which was acquired by Gen-Probe. Dr. Brown is an inventor or co-inventor of more than 85 issued US patents, and earned a Ph.D. in molecular biology from the University of California, Berkeley and B.S. degrees in chemistry and biology from the University of Washington, Seattle.

“I’m honored to join Mammoth Biosciences at such a pivotal moment, as CRISPR technology stands ready to transform healthcare and redefine the future of medicine,” said Dr. Brown. “I look forward to working with the exceptional Mammoth Biosciences team to harness the power of their groundbreaking platform to tackle some of the most pressing medical challenges and improve patients’ lives. Drawing on my experiences in drug discovery and clinical development, I aim to help advance Mammoth Biosciences’ ultracompact CRISPR gene editing therapies—starting with MB-111—toward clinical application.”

About Mammoth Biosciences

Mammoth Biosciences is a biotechnology company focused on leveraging its proprietary ultracompact CRISPR systems to develop potential long-term curative therapies for patients with life-threatening and debilitating diseases. Founded by CRISPR pioneer and Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna and Trevor Martin, Janice Chen, and Lucas Harrington, the company’s ultracompact systems are designed to be more specific and enable

in vivo

gene editing in difficult to reach tissues utilizing both nuclease applications and new editing modalities beyond double stranded breaks, including base editing, reverse transcriptase editing, and epigenetic editing. The company is building out its wholly owned pipeline of potential

in vivo

gene editing therapeutics and capabilities and has partnerships with leading pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to broaden the reach of its innovative and proprietary technology platform. Mammoth Biosciences’ deep science and industry experience, along with a robust and differentiated intellectual property portfolio, have enabled the company to further its mission to transform the lives of patients and deliver on the promise of CRISPR technologies.

SOURCE:

Mammoth Biosciences

Executive ChangeAcquisitionGene TherapyOligonucleotide

14 Apr 2025

A panel of experts who decide the national immunization schedule will meet on Tuesday for the first time in 2025, providing an opportunity for the nation’s top vaccine scientists to publicly discuss the value of products that the new administration has cast doubt on.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices meeting was

postponed

from February and is one of three scheduled for this year. The group is expected to discuss a number of vaccines, including shots protecting against the flu, Covid-19, RSV and meningitis. The group will vote on updated recommendations for chikungunya vaccines, meningococcal vaccines for teens and young adults, and RSV vaccination for adults.

The administration’s scrutiny of these routine meetings reflects how much anti-vaccine sentiment has risen in recent years, and how HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. stands to reinforce those concerns.

“I’m just praying that there will be an ACIP meeting,” Laura Riley, a former ACIP member and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, said in an interview on Monday.

A spokesperson for HHS did not immediately respond when asked about Kennedy’s views of the committee and whether he plans to replace members in the future.

Vaccine policy in the US is effectively divided into two parts. The FDA and its own advisory group review and decide what vaccines to approve. The CDC and ACIP recommend which Americans should get the approved vaccines. Recommended vaccines are usually covered by insurance.

The decisions that ACIP makes, which the CDC director ultimately has final say over, are based on a number of factors, primarily the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. But the committee also considers the cost-effectiveness of the vaccine and the ethics of how certain recommendations, or lack thereof, will impact uptake. The committee reviews vaccine safety data post-licensure, and considers them when updating recommendations.

“Unfortunately, there are so much data out there, and people are not aware of how to interpret it, which is why you need an advisory committee like ACIP poring through all of the data in order to make informed decisions,” said Henry Bernstein, a pediatrics professor at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra University and another former ACIP member who served from 2017 to 2021.

Not in recent memory has ACIP existed under an administration that so frequently questions the benefits of vaccination. Kennedy leads a separate MAHA Commission that he tasked with investigating the childhood vaccine schedule. He’s continuously questioned whether vaccines are the source of rising autism rates, and has initiated plans for the CDC to study just that, despite numerous studies concluding they do not. Specific kinds of vaccines, including mRNA-based and single-antigen vaccines, have been

singled out by either Kennedy

or key voices in the MAHA movement he leads.

Riley said that acceptance of the committee’s work boils down to effective communication, which she says could be improved.

“I don’t think people understand the benefits of science period,” Riley said. “I don’t think that we have communicated clearly enough how important scientific discovery is.”

She pointed to the Covid pandemic as a time when the committee could have more directly explained what it did and didn’t know, given how swiftly new data about the vaccines and the virus were being produced.

“I don’t think that it was clear to people that we didn’t know everything,” she said, adding that it created a vacuum for alternative sources of information to seep in. Sometimes the decisions themselves were polarizing, like when the committee decided in June 2021 that the benefits of the two-shot mRNA Covid vaccine regimen in men outweighed the risk of vaccine-related heart inflammation known as myocarditis.

Kennedy has also questioned whether federal vaccine advisors have a too-cozy relationship with industry.

Politico

previously reported

he was considering replacing some members because of their perceived conflicts. Former ACIP members dismissed the concern, saying the required conflict of interest submissions before each meeting were rigorous and that members frequently erred on the side of caution.

Arthur Reingold, a former committee member and an epidemiology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, told

Endpoints News

that he was barred from voting on a vaccine against HPV because his wife was the director of the CDC’s division of sexually transmitted diseases at the time.

“So if people are saying that all of that was basically hiding things or not fully transparent, I don’t know where that accusation comes from, frankly, or what it’s based on,” he said. The CDC now publishes past conflict of interest disclosures.

Moving forward, Bernstein hopes there isn’t “dramatic change” to the group, calling its work “incredibly successful.”

“What’s being done is critically important, but if we don’t communicate and educate the public at all levels around these vaccines, it’s going to be problematic,” he said.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to include the full titles of Henry Bernstein and Arthur Reingold.

VaccinemRNA

09 Apr 2025

LONG BEACH, Calif. and TORONTO, April 09, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Glass House Brands Inc. ("Glass House" or the "Company") (CBOE CA: GLAS.A.U) (CBOE CA: GLAS.WT.U) (OTCQX: GLASF) (OTCQX: GHBWF), one of the fastest-growing, vertically integrated cannabis companies in the U.S., today announced a collaboration with the University of California, Berkeley, to explore hemp-related research, including novel medicinal product development, identification and improvement of hemp genetics, market analysis, supply chain sustainability, and AI automation for cultivation and production.

In addition, the collaboration aims to evaluate data-driven and evidence-based approaches to hemp policy and regulation, with the aim of reducing uncertainty for California hemp growers. This collaboration will explore potential drug development research opportunities targeting coronaviruses, pain, sleep, inflammation, and cirrhosis.

In 2024, Glass House obtained a hemp license and has been actively growing and testing hemp on an R&D basis. Within the Company’s dedicated hemp R&D greenhouse, Glass House has the capacity to produce up to 240,000 pounds of biomass annually.

“We are excited to work with UC Berkeley as we continue to evaluate our long-term hemp strategy. This is the first collaboration of its kind in this industry, and Berkeley has a successful history of assisting industry stakeholders to find innovative and sustainable solutions to environmental issues. We are confident that through this agreement, we will be better positioned to navigate the local and national legislative uncertainty for the hemp industry as we prepare to scale the business into the future,” said Kyle Kazan, Co-Founder, Chairman and CEO of Glass House Brands. “Furthermore, we appreciate that the premier public university in California is supporting this sector of the agricultural industry, which is substantial in our state. We have the capacity to be one of the largest hemp cultivators in the United States, so we are excited to explore the potential benefits of this collaboration for farmers, the industry and for the state of California. We believe that the demand for hemp-derived products nationally is massive. Pending future developments with the Federal Farm Bill and regulatory changes that align at the state level, we are confident that opportunities to scale to the national market will manifest.”

Orrin Devinsky, MD, Glass House’s Medical and Science Advisor to the Board of Directors and a Professor of Neurology, Neuroscience and Psychiatry, who was the lead investigator in the studies on cannabidiol leading to FDA approval said, “As a long-time proponent of cannabinoids for treatments, I’m excited to collaborate with the research faculty at UC Berkeley to explore the development of new treatments to improve the quality of life for many with disabling disorders.”

About Glass House Brands

Glass House is one of the fastest-growing, vertically integrated cannabis companies in the U.S., with a dedicated focus on the California market and building leading, lasting brands to serve consumers across all segments. From its greenhouse cultivation operations to its manufacturing practices, from brand-building to retailing, the Company's efforts are rooted in the respect for people, the environment, and the community that co-founders Kyle Kazan, Chairman and CEO, and Graham Farrar, Board Member and President, instilled at the outset. Whether it be through its portfolio of brands, which includes Glass House Farms, PLUS Products, Allswell and Mama Sue Wellness or its network of retail dispensaries throughout the state of California, which includes The Farmacy, Natural Healing Center and The Pottery, Glass House is committed to realizing its vision of excellence: outstanding cannabis products, produced sustainably, for the benefit of all. For more information and company updates, visit www.glasshousebrands.com/ and https://ir.glasshousebrands.com/contact/email-alerts/.

Forward Looking Statements

This news release contains certain forward-looking information and forward-looking statements, as defined in applicable securities laws (collectively referred to herein as "forward-looking statements"). Forward-looking statements reflect current expectations or beliefs regarding future events or the Company's future performance or financial results. All statements other than statements of historical fact are forward-looking statements. Often, but not always, forward- looking statements can be identified by the use of words such as "plans", "expects", "is expected", "budget", "scheduled", "estimates", "continues", "forecasts", "projects", "predicts", "intends", "anticipates", "targets" or "believes", or variations of, or the negatives of, such words and phrases or state that certain actions, events or results "may", "could", "would", "should", "might" or "will" be taken, occur or be achieved. Forward-looking statements in this news release include, without limitation, statements regarding the Company's financial outlook or operational plans and statements related to future market conditions. All forward-looking statements, including those herein, are qualified by this cautionary statement. Although the Company believes that the expectations expressed in such statements are based on reasonable assumptions, such statements are not guarantees of future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those in the statements. Accordingly, readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements. There are certain factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those in the forward-looking information, including those risks disclosed in the Company's Annual Information Form available on SEDAR+ at www.sedarplus.ca and in the Company's Form 40-F available on EDGAR at www.sec.gov. For more information on the Company, investors are encouraged to review the Company's public filings on SEDAR+ at www.sedarplus.ca. The forward-looking statements in this news release speak only as of the date of this news release or as of the date or dates specified in such statements. The Company disclaims any intention or obligation to update or revise any forward-looking information, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, other than as required by law.

For further information, please contact:

Glass House Brands Inc.Jon DeCourcey, Vice President of Investor RelationsT: (781) 724-6869E: ir@glasshousebrands.com

Investor Relations Contact:KCSA Strategic CommunicationsPhil CarlsonT: 212-896-1233E: GlassHouse@kcsa.com

100 Deals associated with University of California, Berkeley

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with University of California, Berkeley

Login to view more data

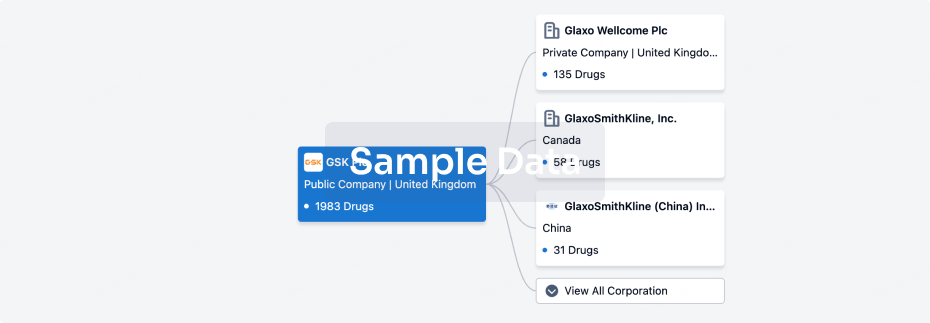

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 21 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

8

4

Preclinical

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Diabeticretinopathy therapy(University of California Berkeley) | Diabetic Retinopathy More | Preclinical |

OTS-964 ( CDK11B x PITSLRE subfamily x TOPK ) | Pre B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia More | Preclinical |

Andrographolide | Prostatic Cancer More | Preclinical |

CS-6253 ( ABCA1 ) | Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2 More | Preclinical |

ML2-9 ( AR ) | - | Discovery |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

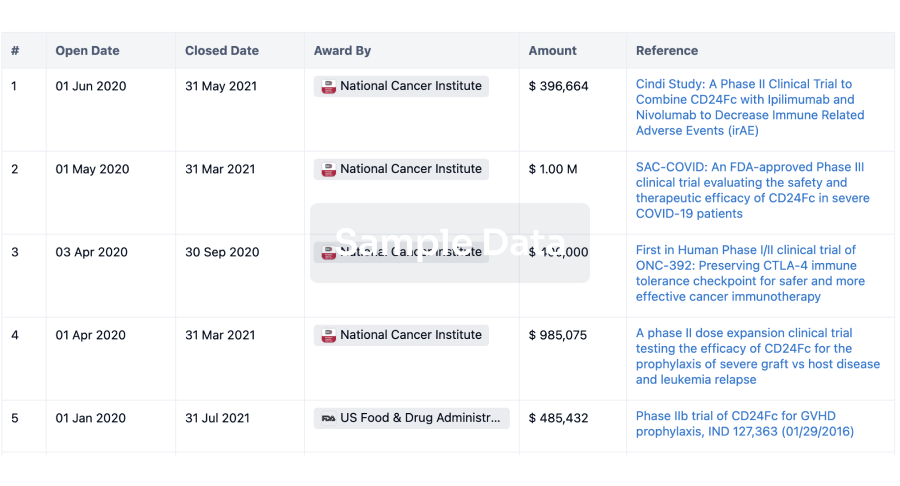

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free