Request Demo

Last update 05 Dec 2025

Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.

Last update 05 Dec 2025

Overview

Tags

Immune System Diseases

Skin and Musculoskeletal Diseases

Digestive System Disorders

Small molecule drug

Fc fusion protein

Fusion protein

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 7 |

| Fc fusion protein | 1 |

| Fusion protein | 1 |

Related

9

Drugs associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.Target |

Mechanism RIPK2 inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism TNFR2 agonists |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

2

Clinical Trials associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.NCT06850727

A Phase 2a, Two-Part, Open-Label and Randomized Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of OD-07656 and of Subsequent Vedolizumab Therapy in Patients With Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of OD-07656 in participants with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC). In addition, the study will evaluate the potential of OD-07656 to enhance the therapeutic benefit of vedolizumab when given after OD-07656.

Start Date02 Jun 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06206811

A Four-part, Phase 1, Double-blind Study to Investigate the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodynamics (PD) with Single and Multiple Ascending Oral Doses of OD-07656 in Healthy, Adult Male and Female Participants

First-in-human study to provide an assessment of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), including food effects and a drug-drug interaction, and pharmacodynamics (PD) of OD-07656 after administration of ascending single and multiple oral doses to healthy male and female participants in view of treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), Blau syndrome, and spondyloarthritis

Start Date12 Feb 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

10

Literatures (Medical) associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.01 Mar 2024·Nature structural & molecular biology

Structural basis for RNA polymerase II ubiquitylation and inactivation in transcription-coupled repair

Article

Author: van der Weegen, Yana ; Wondergem, Annelotte P ; Chernev, Aleksandar ; van der Meer, Paula J ; Fianu, Isaac ; Kokic, Goran ; van den Heuvel, Diana ; Yakoub, George ; Cramer, Patrick ; Lorenz, Sonja ; Luijsterburg, Martijn S ; Fokkens, Thornton J ; Urlaub, Henning

Abstract:

During transcription-coupled DNA repair (TCR), RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transitions from a transcriptionally active state to an arrested state that allows for removal of DNA lesions. This transition requires site-specific ubiquitylation of Pol II by the CRL4CSA ubiquitin ligase, a process that is facilitated by ELOF1 in an unknown way. Using cryogenic electron microscopy, biochemical assays and cell biology approaches, we found that ELOF1 serves as an adaptor to stably position UVSSA and CRL4CSA on arrested Pol II, leading to ligase neddylation and activation of Pol II ubiquitylation. In the presence of ELOF1, a transcription factor IIS (TFIIS)-like element in UVSSA gets ordered and extends through the Pol II pore, thus preventing reactivation of Pol II by TFIIS. Our results provide the structural basis for Pol II ubiquitylation and inactivation in TCR.

01 Oct 2018·Molecular cellQ1 · BIOLOGY

Mode of Action of Kanglemycin A, an Ansamycin Natural Product that Is Active against Rifampicin-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Q1 · BIOLOGY

Article

Author: Yuzenkova, Yulia ; Mosaei, Hamed ; Perry, John David ; Ceccaroni, Lucia ; Moon, Christopher William ; Kepplinger, Bernhard ; Zenkin, Nikolay ; Molodtsov, Vadim ; Bacon, Joanna ; Marrs, Emma Claire Louise ; Allenby, Nicholas Edward Ellis ; Murakami, Katsuhiko S ; Jeeves, Rose Elizabeth ; Harbottle, John ; Errington, Jeff ; Shin, Yeonoh ; Hall, Michael John ; Morton-Laing, Stephanie ; Wills, Corinne ; Clegg, William

Antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens pose an urgent healthcare threat, prompting a demand for new medicines. We report the mode of action of the natural ansamycin antibiotic kanglemycin A (KglA). KglA binds bacterial RNA polymerase at the rifampicin-binding pocket but maintains potency against RNA polymerases containing rifampicin-resistant mutations. KglA has antibiotic activity against rifampicin-resistant Gram-positive bacteria and multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-M. tuberculosis). The X-ray crystal structures of KglA with the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme and Thermus thermophilus RNA polymerase-promoter complex reveal an altered-compared with rifampicin-conformation of KglA within the rifampicin-binding pocket. Unique deoxysugar and succinate ansa bridge substituents make additional contacts with a separate, hydrophobic pocket of RNA polymerase and preclude the formation of initial dinucleotides, respectively. Previous ansa-chain modifications in the rifamycin series have proven unsuccessful. Thus, KglA represents a key starting point for the development of a new class of ansa-chain derivatized ansamycins to tackle rifampicin resistance.

15 Sep 2017·Journal of cell scienceQ2 · BIOLOGY

Screening and purification of natural products from actinomycetes that affect the cell shape of fission yeast

Q2 · BIOLOGY

Article

Author: Errington, Jeffery ; Allenby, Nicholas E. E. ; Lewis, Richard A. ; Nurse, Paul ; Hayles, Jacqueline ; Li, Juanjuan

ABSTRACT:

This study was designed to identify bioactive compounds that alter the cellular shape of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe by affecting functions involved in the cell cycle or cell morphogenesis. We used a multidrug-sensitive fission yeast strain, SAK950 to screen a library of 657 actinomycete bacteria and identified 242 strains that induced eight different major shape phenotypes in S. pombe. These include the typical cell cycle-related phenotype of elongated cells, and the cell morphology-related phenotype of rounded cells. As a proof of principle, we purified four of these activities, one of which is a novel compound and three that are previously known compounds, leptomycin B, streptonigrin and cycloheximide. In this study, we have also shown novel effects for two of these compounds, leptomycin B and cycloheximide. The identification of these four compounds and the explanation of the S. pombe phenotypes in terms of their known, or predicted bioactivities, confirm the effectiveness of this approach.

70

News (Medical) associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.03 Dec 2025

Triana Biomedicines has reeled in a

$120 million

Series B — $10 million higher than its

2022 Series A

— to collect proof-of-concept data for its lead experimental medicine and develop further treatment candidates in the molecular glue space.

The Wednesday morning financing comes a year after the Lexington, MA-based startup struck a $49 million upfront

partnership with Pfizer

. That deal, across multiple therapeutic areas such as oncology, could balloon to more than $1.5 billion in payouts for Triana.

It marks at least the 22nd megaround financing since Sept. 30, according to an

Endpoints News

tally, as the biotech industry has picked up momentum headed into the new year.

Ascenta Capital and Bessemer Venture Partners co-led the Series B. Ascenta has been in the works for years and unveiled its

$325 million first fund

in October. The Florida-based VC firm, from former Moderna leaders Lorence Kim and Evan Rachlin, has backed other drug developers like ADARx, Odyssey Therapeutics and Alpha-9 Oncology.

Kim is joining the Triana board alongside Bessemer’s Andrew Hedin.

Other investors joined Triana’s capitalization table for the first time, including YK Bioventures, Regeneron Ventures, Invus and Finchley Healthcare Ventures. Existing backers like RA Capital and Atlas Venture returned.

RA and Atlas teamed up to form Triana a few years ago. RA had built a machine learning algorithm to find optimal pairings for E3 ligases and target proteins. Meanwhile, Atlas created a way to mine loads of possible molecular glue structures.

At the time of the Pfizer partnership, CEO Patrick Trojer told

Endpoints News

that Triana could get into the clinic as soon as 2026. A spokesperson told Endpoints on Wednesday that Triana expects to enter the clinic by the end of this year. On Thursday, Triana unveiled its lead candidate, called TRI-611. The experimental medicine will be aimed at ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer. Triana said it anticipates selecting a second product candidate next year.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to include a detail on clinical trial timelines from a Triana spokesperson.

03 Dec 2025

Two years after Terray Therapeutics inked a multi-target deal with Bristol Myers Squibb to develop small molecules using its AI technology, the biotech said Wednesday it has achieved a discovery milestone.While Terray can't share too many details about the programme, CEO Jacob Berlin told FirstWord the milestone adds to the company's confidence that its AI platform, dubbed Experimentation Meets Machine Intelligence (EMMI), can deliver across a broad set of target classes and indications. "This milestone highlights one of the key advantages of EMMI — the ability to discover and optimise molecules against difficult and novel targets where there is often little to no previous chemistry knowledge," Berlin said.Reaching the right molecule, fasterThe news follows Terray's unveiling of EMMI in November. The platform combines ultra-miniaturised hardware for molecule testing together with a highly-automated lab and a full-stack AI.Its chemistry foundation model, COATI, now in its third generation, is like "GPT for molecules," according to Terray. By encoding molecules in mathematical latent space, they can be manipulated and investigated by AI models, and "translated" back into molecules when needed. Terray, which raised $120 million in funding last year from investors including NVIDIA and Madrona Ventures, has collected over 13 billion target-molecule measurements into what it calls "the world’s largest precise chemistry dataset" — and it continues to grow at 1 billion measurements per quarter (see – Spotlight On: 'A year of balance' — Realistic expectations for AI in 2025). "EMMI shines by mining this database to find starting points for difficult targets where other approaches have struggled or failed," he noted. The most promising molecules are then optimised with Terray's generative, predictive and selection AI models and evaluated with its experimental workflows for at-scale testing. With EMMI to aid in molecule selection, Terray's benchmarking tests suggest its platform arrived at the best molecule three times faster than other AI technologies, with a similar cost reduction rate. "It is very common to have AI predictions on thousands to millions of molecules, but it is only possible to make and test tens of these in a given week. Picking the right set of molecules has for too long relied on human intuition or basic models that are biased towards the most highly ranked molecules but do not consider how uncertain the ranking is," Berlin explained. "Terray is a pioneer in developing a model that can quantify the uncertainty in the predictions of other models and then optimally select the right set of molecules to test." Series of partnershipsIn addition to its tie-up with BMS, Terray has a discovery deal with Gilead Sciences, similarly focused on "undruggable" targets. The biotech is also working with Google-founded Calico on age-related diseases, and has a collaboration with Odyssey Therapeutics to co-develop compounds against transcription factors for immunology and inflammatory diseases.Internally, Terray is developing an immunology pipeline, though its drug development work is remaining under wraps until "the science is ready," Berlin said. He noted that "EMMI is used across Terray's entire pipeline and has identified and optimised novel chemical scaffolds time and time again."

17 Nov 2025

AI models can easily generate tons of potential molecules on a computer screen. But that leads to the problem of deciding which to synthesize in the real world.

Terray Therapeutics has developed an AI method that outperformed its own team of expert chemists in making those selections.

The Pasadena, CA-based startup has built a selection model, sharing details Monday via a preprint article and corporate blog. Terray is doing so as a part of the debut of its broader AI platform called EMMI, short for “experimentation meets machine intelligence,” CEO Jacob Berlin told

Endpoints News

.

Monday’s disclosure is Terray’s most substantive update of 2025, after a newsy 2024 that included

raising a $120 million Series B round

and signing research deals with

Gilead

and

Odyssey Therapeutics

. Terray’s AI-driven selection method gives a look into how it has focused on building models beyond the popular areas of predicting molecular structures and generating new molecules.

Terray’s selection model builds on top of an epistemic neural network architecture, or a type of AI model effectively designed to manage uncertainty that was

first introduced by a Google DeepMind team

in 2021.

In one retrospective experiment detailed in the preprint, Terray tried three approaches in finding the most potent binders to EGFR, a popular drug target, among roughly 50,000 compounds. One mainly relied on human chemists picking which molecules to make for up to 30 rounds of lab testing. A second approach was Terray’s previous standard, using computational methods that made clusters for different chemical structures, ensuring a basket with a range of different-looking molecules. The third was its latest selection model.

Terray’s selection model outperformed the two other options, Berlin said, getting to a desired outcome that was about two-thirds faster and cheaper.

That has impacted how Terray runs its labs, he added. A single cycle of synthesizing and testing molecules in the lab typically takes one or two weeks. The selection model was about 20 cycles faster than the other methods, meaning it could save anywhere from six months to up to a year on a drug campaign.

“The only thing that matters in this industry is real winners — the molecules you’re actually going to put in the clinic,” Berlin said. “By saving 50-plus percent on your synthesis and your testing time, you can get to better answers.”

Terray is open-sourcing the selection model, Berlin said.

“As this gets out in the world, probably everyone will run some variant of this over the coming years,” he said. “We’ll just happen to be the first.”

That outperformance challenges a status quo of biotech labs, where chemists have long relied on their expertise and intuition in deciding which molecules are best to make and test.

Even when using computational methods, Berlin said his understanding is that oftentimes final choices are still made by human experts, who may factor in a model’s suggestions. The selection model suggests that the right AI model could be superior in balancing the countless factors and uncertainties behind human decisions.

Terray will share updates to a range of its other AI models as well. That notably includes TerraBind, a model predicting binding potency, which it first developed in 2023 but has never publicly discussed. Berlin said it is faster and cheaper than Boltz-2, a popular open-source model for potency predictions

developed by an MIT team earlier this year

.

“We never told anybody about our TerraBind predictive potency model for two whole years, until Boltz told the world about something that’s not as good as ours,” Berlin said.

Terray has not publicly shared performance data in comparing TerraBind to Boltz-2. Berlin said Terray would probably publish on the next iteration of TerraBind in 2026.

That progression also tracks the 130-employee biotech’s focus on applying AI models to actual drug programs. Terray was founded in 2018 by Berlin, who left a tenured professorship at City of Hope to advance his research on a nickel-sized microarray chip that can measure binding activity for millions of molecules. The EMMI platform stitches together a range of AI research that builds off the massive experimental data trove coming off those chips.

Terray’s lead asset is a brain-penetrant inhibitor for multiple sclerosis that is nearing selection of a development candidate. Berlin said it could enter the clinic in late 2026 or in 2027. Berlin said the AI bio field is starting to move beyond a focus on besting metrics in papers to helpful results in the real lab.

“Outperforming on a benchmark is a nice validation that you’re on the right path and have built something that is impactful,” Berlin said. “Seeing it change your ROI and your speed of execution and your actual pipeline is the next step. The ultimate realization has to be molecules that change human health and provide value.”

100 Deals associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Odyssey Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

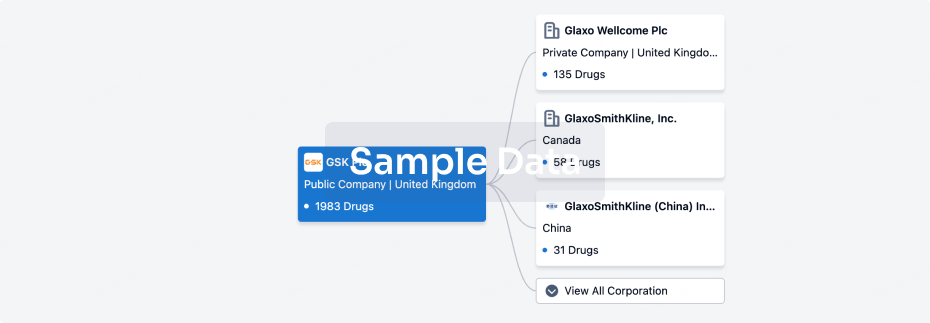

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 05 Mar 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

4

4

Preclinical

Phase 2

1

10

Other

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

OD-07656 ( RIPK2 ) | Colitis, Ulcerative More | Phase 2 |

IRAK4 inhibitor (Odyssey) ( IRAK4 ) | Hidradenitis Suppurativa More | Preclinical |

OD-00910 ( TNFR2 ) | Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1 More | Preclinical |

ODY-CDK ( CDK2 ) | Ovarian Cancer More | Preclinical |

Natural product antibiotics (Demuris) | Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

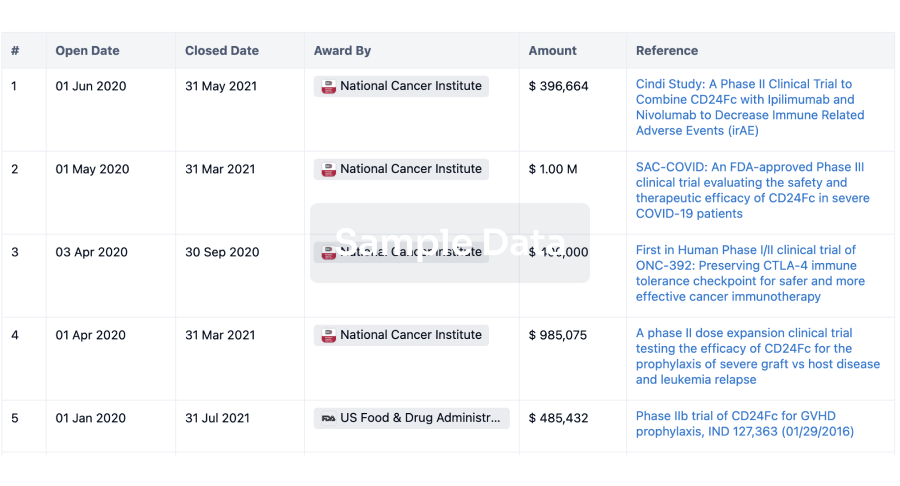

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free