Request Demo

Last update 04 Mar 2026

Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.

Last update 04 Mar 2026

Overview

Tags

Immune System Diseases

Nervous System Diseases

Digestive System Disorders

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Nervous System Diseases | 3 |

| Immune System Diseases | 3 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 3 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| SPNS2(sphingolipid transporter 2) | 3 |

Related

3

Drugs associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.Target |

Mechanism SPNS2 inhibitors |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism SPNS2 inhibitors |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism SPNS2 inhibitors |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

100 Clinical Results associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.

Login to view more data

8

Literatures (Medical) associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.01 Jul 2019·Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular and cell biology of lipidsQ2 · BIOLOGY

The role of cardiolipin concentration and acyl chain composition on mitochondrial inner membrane molecular organization and function

Q2 · BIOLOGY

Review

Author: Brown, David A ; Funai, Katsuhiko ; Shaikh, Saame Raza ; Pennington, Edward Ross

Cardiolipin (CL) is a key phospholipid of the mitochondria. A loss of CL content and remodeling of CL's acyl chains is observed in several pathologies. Strong shifts in CL concentration and acyl chain composition would presumably disrupt mitochondrial inner membrane biophysical organization. However, it remains unclear in the literature as to which is the key regulator of mitochondrial membrane biophysical properties. We review the literature to discriminate the effects of CL concentration and acyl chain composition on mitochondrial membrane organization. A widely applicable theme emerges across several pathologies, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, Barth syndrome, and neurodegenerative ailments. The loss of CL, often accompanied by increased levels of lyso-CLs, impairs mitochondrial inner membrane organization. Modest remodeling of CL acyl chains is not a major driver of impairments and only in cases of extreme remodeling is there an influence on membrane properties.

01 Oct 2018·The Journal of biological chemistryQ2 · BIOLOGY

Proteolipid domains form in biomimetic and cardiac mitochondrial vesicles and are regulated by cardiolipin concentration but not monolyso-cardiolipin

Q2 · BIOLOGY

Article

Author: Coleman, Rosalind A ; Schlattner, Uwe ; DeSantis, Anita ; Zeczycki, Tonya N ; Shaikh, Saame Raza ; Chicco, Adam J ; Fix, Amy ; Brown, David A ; Dadoo, Sahil ; Sullivan, E Madison ; Pennington, Edward Ross

Cardiolipin (CL) is an anionic phospholipid mainly located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it helps regulate bioenergetics, membrane structure, and apoptosis. Localized, phase-segregated domains of CL are hypothesized to control mitochondrial inner membrane organization. However, the existence and underlying mechanisms regulating these mitochondrial domains are unclear. Here, we first isolated detergent-resistant cardiac mitochondrial membranes that have been reported to be CL-enriched domains. Experiments with different detergents yielded only nonspecific solubilization of mitochondrial phospholipids, suggesting that CL domains are not recoverable with detergents. Next, domain formation was investigated in biomimetic giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) and newly synthesized giant mitochondrial vesicles (GMVs) from mouse hearts. Confocal fluorescent imaging revealed that introduction of cytochrome c into membranes promotes macroscopic proteolipid domain formation associated with membrane morphological changes in both GUVs and GMVs. Domain organization was also investigated after lowering tetralinoleoyl-CL concentration and substitution with monolyso-CL, two common modifications observed in cardiac pathologies. Loss of tetralinoleoyl-CL decreased proteolipid domain formation in GUVs, because of a favorable Gibbs-free energy of lipid mixing, whereas addition of monolyso-CL had no effect on lipid mixing. Moreover, murine GMVs generated from cardiac acyl-CoA synthetase-1 knockouts, which have remodeled CL acyl chains, did not perturb proteolipid domains. Finally, lowering the tetralinoleoyl-CL content had a stronger influence on the oxidation status of cytochrome c than did incorporation of monolyso-CL. These results indicate that proteolipid domain formation in the cardiac mitochondrial inner membrane depends on tetralinoleoyl-CL concentration, driven by underlying lipid-mixing properties, but not the presence of monolyso-CL.

01 May 2018·Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.)Q2 · MEDICINE

Mechanisms by Which Dietary Fatty Acids Regulate Mitochondrial Structure-Function in Health and Disease

Q2 · MEDICINE

Review

Author: Brown, David A ; Beck, Melinda A ; Shaikh, Saame Raza ; Green, William D ; Sullivan, E Madison ; Pennington, Edward Ross

Mitochondria are the energy-producing organelles within a cell. Furthermore, mitochondria have a role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and proper calcium concentrations, building critical components of hormones and other signaling molecules, and controlling apoptosis. Structurally, mitochondria are unique because they have 2 membranes that allow for compartmentalization. The composition and molecular organization of these membranes are crucial to the maintenance and function of mitochondria. In this review, we first present a general overview of mitochondrial membrane biochemistry and biophysics followed by the role of different dietary saturated and unsaturated fatty acids in modulating mitochondrial membrane structure-function. We focus extensively on long-chain n-3 (ω-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids and their underlying mechanisms of action. Finally, we discuss implications of understanding molecular mechanisms by which dietary n-3 fatty acids target mitochondrial structure-function in metabolic diseases such as obesity, cardiac-ischemia reperfusion injury, obesity, type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and select cancers.

2

News (Medical) associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.12 Apr 2023

Using satellite-obtained data from 2007-21, researchers mapped the entire East Coast to demonstrate how the inclusion of land subsidence reveals many areas to be more vulnerable to floods and erosion than previously thought.

It's been said that a rug can really tie a room together. In a similar fashion, Manoochehr Shirzaei and his research team are hoping that weaving together millions of data points into terrain-covering, digital maps can help connect the realities of sinking landscapes to the overall impact of climate change.

"It's like a carpet over the desert," Shirzaei, associate professor of radar remote sensing engineering and environmental security, said of a recent projection of land in Arizona. "You can clearly see that area is just massively sinking into the ground. And we've created these maps for dozens of major cities in the United States and monitor another 50 airports globally."

Using publicly available satellite imagery, Shirzaei and the 15 student and postdoctoral researchers at Virginia Tech's Earth Observation and Innovation Lab measure millions of occurrences of sinking land, known as land subsidence, spanning multiple years. They then create some of the world's first high-resolution depictions of the land subsidence, which when combined with other observations, such as sea-level rise, provide more clear projection of the potential impact of floods and natural disasters during the next 100 years.

Most recently, the lab's mapping served as the foundation for graduate student Leonard Ohenhen's findings published in Nature Communications, a British science journal. Using satellite-obtained data from 2007-21, Ohenhen mapped the entire East Coast to demonstrate how the inclusion of land subsidence reveals many areas to be more vulnerable to floods and erosion than previously thought.

"We saw places like New York City and Charleston [South Carolina] are sinking up to as much as two millimeters per year," said Ohenhen, one of the lab's graduate students. "It really shows the hidden vulnerability of the Atlantic East Coast to sea-level rise."

The unique, high-resolution maps crafted in the Earth Observation and Innovation Lab also have drawn the attention of multiple government agencies. This has led to the investment of millions of external dollars in an effort fill a critical gap of information and help people better plan at the local, state, federal, and global level.

"One of the big uncertainties we have is how the land is moving up or down through time, so we've turned to Manoo," said Patrick Barnard, a research geologist with the United States Geologic Service (USGS). "This information is needed, no one else is providing it, and Manoo's stepped into that niche with his technical expertise and is providing something extremely valuable."

Land movement can be the result of natural processes, such as tectonics, glacial isostatic adjustment, sediment loading, and soil compaction, but can also result from human behaviors, such as extracting groundwater and gas and oil production.

Barnard said the vertical land motion rates provided have helped the USGS produce better models and give better guidance to other agencies in terms of managing and mitigating the risk of flooding. This impacts everything from real estate values and building plans to hurricane evacuation routes and the location of future levees.

The Earth Observation and Innovation Lab played a key role in recent USGS projections of future hazards on the Atlantic coast. The project consists of several data sets that map future coastal flooding and erosion hazards due to sea level rise and storms for Florida, Georgia, and Virginia with a range of plausible scenarios through 2100.

"Having this collaboration helps us refine the risk to lives and dollars communities face from sea level rise and storms," Barnard said. "This is a really valuable data set they provide."

Bringing such realities into focus for the average person is at the heart of Shirzaei's efforts and the work of the lab.

"We're creating access to actionable data that will help people become resilient when it comes to national and environmental security," Shirzaei said. "The data we're providing, we're making it more than just open access, we're making it usable by everybody. You don't have to have a Ph.D. to use it. That's our niche here."

Shirzaei joined the College of Science in fall 2020, alongside his spouse, Susanna Werth, assistant professor of hydrology and remote sensing. Shirzaei's Earth Observation and Innovation Lab and Werth's Hydrologic Innovation and Remote Sensing Lab work in tandem, utilizing the same space, much of the same technology, and even sharing student researchers.

Having previously worked together in Arizona, the pair was drawn across the country by the community feel they found in the New River Valley.

"Virginia Tech is a great school, but what we really like is the environment Blacksburg provides for our family," Shirzaei said.

Both students of geodesy -- the science of modeling the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of the Earth -- Werth said their work with remote sensing methods from satellites taps into interests that she'd long had.

"I was always very fascinated with observing stuff from space, how without touching the ground, you can see somethings there so much better," Werth said. "And I was also very fascinated by water, so observing the water cycle with space observation methods is ideal."

Shirzaei said he was first turned on to the idea of using satellite data to observe the Earth, rather than going out to physical locations, during a geophysics and remote sensning conference about 20 years ago.

"I saw everyone like me dirty coming in from field work except for a bunch of Italian guys in ties and suits," he said. "Their hands were clean. They smelled like perfume. And I said, I want to be these guys."

The group presented a paper on using Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar, commonly called InSAR, obtained from satellites. InSAR makes high-density measurements over large areas by using radar to measure changes in land-surface altitude at high degrees of measurement resolution and spatial detail.

Shirzaei jumped at the opportunity to learn this new research method, but faced initial hurdles due to his Iranian citizenship.

"Now I'm an American, but at the time, if I wanted to access the data, just me emailing one of them would have been a violation," Shirzaei said. "So I had to build everything myself and I began writing code from scratch. It took a little bit longer, but I think it was good for me."

The tools Shirzaei developed provided the foundation for the Earth Observation and Innovation Lab, which he said is constantly evolving based on the most relevant problems that need to be solved.

"This data has been around for years. What's made the data revolutionary is the way we process them," Shirzaei said. "To get these kinds of maps, you need a technology that is rare. And then, all we do is look for a good niche application to add value to it and communicate that to people."

The lab's current projects include:

"We are funded by tax dollars, so we really want to make sure our work is relevant for tax payers," Shirzaei said. "For that reason, I've completely changed my lab's direction serval times over the past eight or nine years. Because the mission is important, it's worth the risk."

The lab's mission has drawn the interest of a diverse population of student researchers. Students like Sonam Sherpa, a graduate student who followed Shirzaei from Arizona, and Mohammad Khorrami, a graduate student who changed his major as a result of the lab experience, make up a team of students representing eight different nationalities.

"That helps understanding how different groups in the world perceive the challenge we face, especially with sea level rising," said Oluwaseyi Dasho, one of the lab's graduate student researchers. "It really helps us further solve these problems."

Shirzaei said the lab has the funding and workload to support as many as 25 students and hopes to expand as soon as the physical space allows for it. It plans to relocate to the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center in May.

The Earth Observation and Innovation Lab is the reason Ohenhen decided to attend Virginia Tech. He said working in the lab not only allows him to do the type of research in his recently published paper, but it also echoes his passion for helping communicate actionable information to others.

Along with flood projections for the entire East Coast, part of the paper published in Nature highlights the vulnerability of the wetlands, which often provide a barrier between floods and people by absorbing flood waters slowly. Ohenhen said he hopes his research makes clear that ecosystem's importance to the residents of those areas.

"Protect the wetlands is the overall message to the average person," Ohenhen said. "Most people, they try to protect just enough of their property and leave other areas like the wetlands to basically fend for own survival. But when we do that, we're really just creating a greater threat for ourselves."

Shirzaei said he hopes the maps created for Ohenhen's paper are used by policymakers and leaders to prevent areas from remaining undefended from flood waters. Similarly, he hopes the Earth Observation and Innovation Lab as a whole continues to be utilized in ways that help people better understand and prepare for potential risks.

"At the moment, the problem a lot of people have is they don't know the hazard that might come in the future," Shirzaei said. "Our data will help them understand that and come up with better plans for the future."

04 Oct 2006

RADFORD, Va., Oct. 3 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- New River Pharmaceuticals Inc. announced today that Garen Z. Manvelian, M.D., has joined the company as Chief Medical Officer. Dr. Manvelian will operate from the company's laboratories at the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center in Blacksburg, Virginia, and will report to Krish S. Krishnan, New River's Chief Operating Officer and Chief Financial Officer.

Krishnan remarked, "Dr. Manvelian is a welcome addition to New River's leadership team. His training and expertise will be an asset to the clinical development of New River's product candidates."

Dr. Manvelian comes to New River from SkyePharma Inc., where he served since 2000 as Senior Director, Clinical and Medical Affairs. Prior to that, he served as a Clinical Research Scientist at Quintiles CNS Therapeutics.

Dr. Manvelian holds an M.D. degree from the Vitebsk State Medical Institute in Vitebsk, Belarus. He completed a residency program in anesthesiology at the Republic Hospital of Armenia in Yerevan, Armenia, and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Yale University School of Medicine Department of Anesthesiology.

Dr. Manvelian commented, "I look forward to working with the New River team. I am excited about the promise of New River's current and future clinical projects and am eager to apply my experience to help advance the company's compounds toward regulatory approval."

About New River

New River Pharmaceuticals Inc. is a specialty pharmaceutical company developing novel pharmaceuticals that are generational improvements of widely prescribed drugs in large and growing markets.

For further information on New River, please visit the Company's Web site at .

"SAFE HARBOR" STATEMENT UNDER THE PRIVATE SECURITIES LITIGATION REFORM ACT OF 1995

This press release contains certain forward-looking information that is intended to be covered by the safe harbor for "forward-looking statements" provided by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Forward-looking statements are statements that are not historical facts. Words such as "expect(s)," "feel(s)," "believe(s)," "will," "may," "anticipate(s)" and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. These statements include, but are not limited to, financial projections and estimates and their underlying assumptions; statements regarding plans, objectives and expectations with respect to future operations, products and services; and statements regarding future performance. Such statements are subject to certain risks and uncertainties, many of which are difficult to predict and generally beyond the control of New River Pharmaceuticals, that could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied or projected by, the forward-looking information and statements. These risks and uncertainties include: those discussed and identified in the New River Pharmaceuticals Inc. annual report on Form 10-K, filed with the SEC on March 15, 2006; the timing, progress and likelihood of success of our product research and development programs; the timing and status of our preclinical and clinical development of potential drugs; the likelihood of success of our drug products in clinical trials and the regulatory approval process; our drug products' efficacy, abuse and tamper resistance, resistance to intravenous abuse, onset and duration of drug action, ability to provide protection from overdose, ability to improve patients' symptoms, incidence of adverse events, ability to reduce opioid tolerance, ability to reduce therapeutic variability, and ability to reduce the risks associated with certain therapies; the ability to develop, manufacture, launch and market our drug products; our projections for future revenues, profitability and ability to achieve certain sales targets; our estimates regarding our capital requirements and our needs for additional financing; the likelihood of obtaining favorable scheduling and labeling of our drug products; the likelihood of regulatory approval under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act without having to conduct long and costly trials to generate all of the data which are often required in connection with a traditional new chemical entity; our ability to develop safer and improved versions of widely prescribed drugs using our Carrierwave (TM) technology; our success in developing our own sales and marketing capabilities for our lead product candidate, NRP104; and our ability to obtain favorable patent claims. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements that speak only as of the date hereof. New River Pharmaceuticals does not undertake any obligation to republish revised forward-looking statements to reflect events or circumstances after the date hereof or to reflect the occurrence of unanticipated events. Readers are also urged to carefully review and consider the various disclosures in New River Pharmaceuticals' annual report on Form 10-K, filed with the SEC on March 15, 2006, as well as other public filings with the SEC.

Contacts:

The Ruth Group

John Quirk (investors)

646-536-7029

jquirk@theruthgroup.com

Zack Kubow (media)

646-536-7020

zkubow@theruthgroup.com

New River Pharmaceuticals Inc.

CONTACT: Investors, John Quirk, +1-646-536-7029, jquirk@theruthgroup.com,or Media, Zack Kubow, +1-646-536-7020, zkubow@theruthgroup.com, both of TheRuth Group for New River Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Web site:

100 Deals associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Inc.

Login to view more data

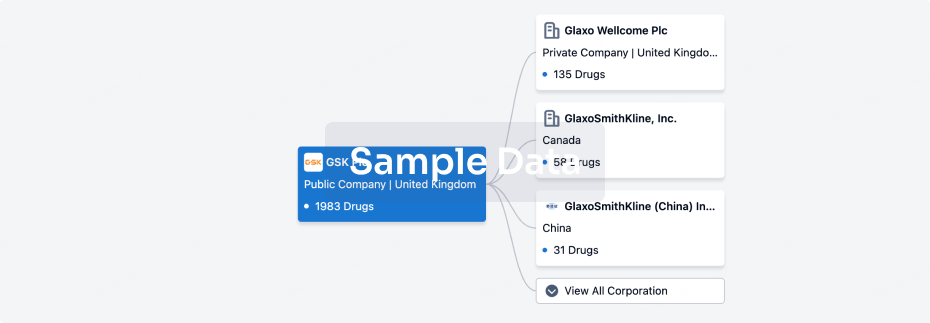

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 04 Mar 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Preclinical

3

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

SLF-1081851 ( SPNS2 ) | Colitis, Ulcerative More | Preclinical |

SLF-80721166 ( SPNS2 ) | Colitis, Ulcerative More | Preclinical |

SLF-80821178 ( SPNS2 ) | Colitis, Ulcerative More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

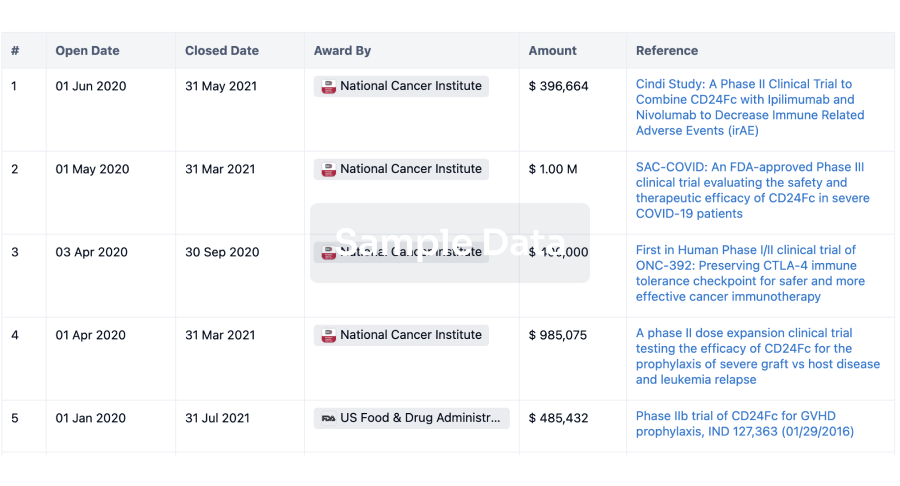

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free