Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)

Private Company|Tennessee, United States

Private Company|Tennessee, United States

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Tags

Endocrinology and Metabolic Disease

Skin and Musculoskeletal Diseases

Growth factors

Enzyme

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Endocrinology and Metabolic Disease | 1 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Growth factors | 1 |

| Enzyme | 1 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| PDGFRβ(Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta) | 1 |

| Collagen | 1 |

Related

2

Drugs associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)Target |

Mechanism PDGFRβ agonists |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date16 Dec 1997 |

Target |

Mechanism Collagen inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date04 Jun 1965 |

179

Clinical Trials associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)NCT06916728

A Post Approval Multicenter 10 Year Follow-up Observational Trial of Marketed Product - MP01 vs. Surgical Standard of Care (SSOC) Used for the Treatment of Joint Surface Lesions of the Knee

The purpose of the study is to support market adoption and global market access via collection of long-term effectiveness, safety, and radiographic data. The primary hypothesis is that Marketed Product (MP01) retains its superiority over Surgical Standard of Care (SSOC) at 7 years in term of mean improvement in the overall Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS).

Start Date01 Apr 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06831448

An Open-label, Prospective, Comparative Human Participant Study to Evaluate the Clinically Acceptable Dressing Presence and Conformability Properties of a Prototype Multilayer Foam Dressing in Comparison to ALLEVYN◊ LIFE and Another Established Medical Device.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate a new prototype multilayer foam dressing on healthy, intact skin.

The study will find out how well the new prototype dressing stays in place as well as other dressing performance and safety factors when compared to two corresponding, marketed dressings with a similar intended use profile and shape.

The study will compare:

1. Prototype dressing vs Marketed dressing 1 on thighs and shins.

2. Prototype dressing vs Marketed dressing 2 on thighs and shins.

The main aim of the study is to show that the new prototype dressing is not worse than the established marketed comparison dressings in terms of staying in place on human participants at 7 days.

Dressings will have successfully stayed in place if the dressing edges have not lifted to reach the pad, and the pad is not exposed in any way.

Additional data will be collected to further support product performance up to 7 days, including safety information and potential device issues.

The study will find out how well the new prototype dressing stays in place as well as other dressing performance and safety factors when compared to two corresponding, marketed dressings with a similar intended use profile and shape.

The study will compare:

1. Prototype dressing vs Marketed dressing 1 on thighs and shins.

2. Prototype dressing vs Marketed dressing 2 on thighs and shins.

The main aim of the study is to show that the new prototype dressing is not worse than the established marketed comparison dressings in terms of staying in place on human participants at 7 days.

Dressings will have successfully stayed in place if the dressing edges have not lifted to reach the pad, and the pad is not exposed in any way.

Additional data will be collected to further support product performance up to 7 days, including safety information and potential device issues.

Start Date27 Jan 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06264999

Gait Analysis, Stair Performance and CT-based Micromotion Analysis in Robotic Assisted Total Knee Arthroplasty Comparing Bi-cruciate Retaining vs Cruciate Retaining Implants: A Single Centre Patient-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial

The goal of this clinical trial is to compare the function of the knee after retaining or sacrificing the anterior cruciate ligament in robotic assisted knee arthroplasty.

The main questions it aims to answer are:

Does retaining the anterior cruciate ligament improve postoperative gait? Participants will perform

* Gait analysis

* Stair performance test

* CT based Micromotion analysis of the implant micromovement

The main questions it aims to answer are:

Does retaining the anterior cruciate ligament improve postoperative gait? Participants will perform

* Gait analysis

* Stair performance test

* CT based Micromotion analysis of the implant micromovement

Start Date01 Jan 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)

Login to view more data

14

News (Medical) associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)31 Mar 2025

FRANKLIN, TN, USA I March 31, 2025 I

Lynch Regenerative Medicine, LLC., (LRM) announced today that it has acquired exclusive rights to REGRANEX® gel and recombinant purified platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) from Smith & Nephew, Inc., for use in skin rejuvenation and regeneration as well as other soft tissue wound healing and tissue regeneration applications. PDGF is the first and only pure recombinant growth factor to have received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of wounds in the lower extremities of diabetic patients. The terms of the transaction were not disclosed.

The prevalence of diabetes is rising, with an estimated 38.4 million people in the United States, or 11.6% of the population, suffering from diabetes in 2021. Of those patients, 15% are likely to experience a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU). Approximately 85% of diabetes-related lower extremity amputations are preceded by a DFU, and most of these amputations are preventable. REGRANEX is a proven first-line treatment for DFUs when used as an adjunct to good ulcer care. It has been demonstrated in Phase III randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials to significantly increase healing of DFUs, as compared to a standard good ulcer care. Under the terms of the transaction, Smith & Nephew will continue to distribute REGRANEX through August 2025, after which LRM will become the exclusive manufacturer and seller of REGRANEX.

LRM is working with leading universities and skin care centers in the United States to identify and develop new formulations of recombinant pure PDGF for additional wound healing and skin rejuvenation and regeneration indications beyond DFUs.

“We are excited to acquire the exclusive rights to use recombinant cGMP pure PDGF for soft tissue and wound healing indications. These rights complement our existing broad patent portfolio covering the composition and use of PDGF for skin rejuvenation and regeneration and hair restoration. I have led the development of five pure PDGF products for tissue regeneration and rejuvenation and am confident that we can successfully develop pure PDGF for additional indications in skin and other soft tissue applications,” said Dr. Samuel Lynch, founder and CEO of LRM and inventor on more than 150 patents worldwide and author of more than 100 peer-reviewed articles on PDGF and regenerative medicine.

“PDGF is the most powerful, most important growth factor so far discovered for stimulating healing, tissue regeneration and rejuvenation. Our mission at LRM is to harness the power of PDGF to help patients heal skin and other soft tissue wounds faster and with less scarring, and to rejuvenate the skin to achieve optimum aesthetic results. Our vision is that it becomes best practice for every surgical incision and every injury to skin to be treated with pure PDGF to accelerate healing, reduce inflammation and pain, and decrease the opportunity for wounds to become infected,” added Dr. Lynch.

Recombinant pure PDGF has a strong record of regulatory approval in numerous clinical indications. PDGF has been through multiple phase I – IV clinical trials and has received FDA approval four times – twice as an alternative to autograft in arthrodesis (i.e., surgical fusion procedures) of the ankle (tibiotalar joint) and/or hindfoot (including subtalar, talonavicular, and calcaneocuboid joints, alone or in combination), due to osteoarthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, avascular necrosis, joint instability, joint deformity, congenital defect, or joint arthropathy in patients with preoperative or intraoperative evidence indicating the need for supplemental graft material; once for promoting periodontal regeneration including regeneration of bone and soft tissues lost due to periodontal disease; and once for promoting healing of chronic skin wounds in the lower extremities of diabetic patients.

In addition, LRM, through its wholly owned LRM Aesthetics company, has recently introduced its first commercial product, Ariessence

TM

pure PDGF+, to the aesthetics market, where it is rapidly gaining adoption as the go-to topical product for skin rejuvenation and improved aesthetic results following laser therapy, microneedling and other skin rejuvenation procedures.

About Lynch Regenerative Medicine, LLC

Lynch Regenerative Medicine, LLC., is a commercial stage biotech company pioneering innovative treatments that aim to revolutionize aesthetics and wound care through skin rejuvenation and regeneration, so that patients can rediscover the joy of healthy skin and natural beauty. LRM is advancing the $100 billion aesthetics and wound-care markets by leveraging our regenerative medicine heritage, and our decades-long commitment to safe and effective regenerative products of the highest quality. LRM’s first solution to come to the market, Ariessence

TM

Pure PDGF+

(

www.ariessence.com

)

, is on the market today and can be found in leading innovative med/spa clinics, and other aesthetic focused offices including dermatology and plastic surgery practices. The company was founded in 2023 by Dr. Samuel Lynch and is based in Franklin, Tennessee.

Select Safety Information for REGRANEX® Gel

REGRANEX is the only FDA-approved PDGF indicated for the treatment of lower extremity diabetic neuropathic ulcers that extend into the subcutaneous tissue or beyond and have an adequate blood supply. REGRANEX is indicated as an adjunct to, and not a substitute for, good ulcer care practices.

Limitations of use:

Contraindication: REGRANEX is contraindicated in patients with known neoplasm(s) at the site(s) of application.

Warnings and Precautions: The benefits and risks of treatment should be carefully evaluated before prescribing in patients with known malignancy.

If application site reactions occur, consider the possibility of sensitization or irritation caused by parabens or mcresol. Interrupt treatment and evaluate (e.g. patch testing) as appropriate.

For complete product information, please see the

REGRANEX Full Prescribing Information

.

SOURCE:

Lynch Regenerative Medicine

Phase 1Phase 3Drug Approval

14 Jul 2023

BELLEVUE, Wash.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- CurvaFix, Inc., a developer of medical devices to repair fractures in curved bones, today announced the close of a $39 million equity financing led by MVM Partners with participation from Sectoral Asset Management and other existing investors. The company also announced that Mark Foster has been named CEO, succeeding founder and current CEO Steve Dimmer, who will transition into a strategic advisory role.

Financing

Proceeds from the $39 million financing will be used to expand the treatment of Fragility Fractures of the Pelvis (FFP) throughout the U.S. and fundamentally change the course of care for these patients through the nationwide launch of the CurvaFix® IM Implant.

“CurvaFix's ability to benefit patients, physicians, and health systems, while simultaneously addressing the undertreated FFP segment makes CurvaFix a rare asset in the crowded world of orthopedics,” said Eric Fritz, MVM Partner. “We are thrilled to be involved and look forward to supporting the company’s next phase of growth.”

CEO Transition

Foster is an experienced C-Suite executive with a broad background in the healthcare, medical device, and pharmaceutical industries. Before joining CurvaFix, Foster was president and CEO of Trice Medical, a leader in the field of minimally invasive orthopedic procedures. Formerly he was V.P. of U.S. Sports Medicine Business for Smith and Nephew and also held leadership roles at Boston Scientific.

“I have had the opportunity to observe the successful implementation and adoption of CurvaFix IM Implants in the orthopedic pelvic fracture fixation market, for which Steve has played a pivotal role in taking the company to this point,” Foster said. “I am looking forward to leading the CurvaFix team in scaling CurvaFix’s technology to benefit many more patients, physicians, and payers.”

“It has been a privilege to lead CurvaFix from concept through commercialization to where it is today, and I am honored to pass off the reins to Mark for this next exciting phase of CurvaFix’s growth,” said Dimmer.

About MVM Partners

MVM has invested in high-growth healthcare businesses since 1997. With teams in Boston and London, MVM has a broad, global investment outlook spanning medical technology, pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, contract research and manufacturing, digital health, and other sectors of healthcare. More information can be found at .

About CurvaFix, Inc.

CurvaFix, Inc. is a privately held medical device company headquartered in Bellevue, Wash. The company is developing implantable products to improve fracture repair in curved bones and is focusing on Fragility Fractures of the Pelvis (FFP), high-energy and low-impact trauma pelvic fractures. The CurvaFix IM Implant has received 510(k) clearance from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA).

Executive Change

23 Feb 2023

EDINBURGH, Scotland, Feb. 23, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- TC BioPharm (Holdings) PLC ("TC BioPharm" or the "Company") (NASDAQ: TCBP) a clinical stage biotechnology company developing platform allogeneic gamma-delta T cell therapies for cancer, today announced the appointment of Dr. Michael Leek to the position of Chief Technology Officer. Dr. Leek resumes operational duties as CTO after stepping down as executive chairman of the board.

With more than 35 years experience in cell-based research and development, Co-founder, Michael Leek, Ph.D., had previously served as TC BioPharm's Executive Chairman of the board since June 2021. Prior he served as Chief Executive of TC BioPharm since founding the Company in July 2013. He has served in senior management and board roles with, Intercytex plc, a cell therapy company he co-founded. While at Intercytex, Dr. Leek was involved in clinical development of cell therapies to treat chronic dermal wounds. Early in his career, he held roles of increasing responsibility at Smith and Nephew from 1989 to 1999 as leader of the Tissue Repair Enabling Technology team. Dr. Leek holds a Ph.D. (Forensic Medicine) from the University of Leeds. He has acted as an honorary lecturer at the School of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen since January 2014.

"I am excited to rejoin the TC BioPharm operational team and help drive the company's technology forward," said Leek. "I look forward to working with Bryan, the executive team and the board to continue the Company's trajectory as leader in the discovery, development and commercialization of gamma-delta T cell therapies for the treatment of cancer and other severe diseases."

"We welcome Dr. Leek back to TC BioPharm's C-Suite in this new role," said Bryan Kobel, Chief Executive Officer. "His contributions to TC Biopharm since inception have been invaluable and I'm appreciative of Mike's strong desire to be more involved on a day-to-day basis. The innovation task force we created several months ago will report to Dr. Leek and together they've already made great strides in reviewing potential combination therapies and new opportunities for TCBP and I expect the team to continue to excel going forward."

About TC BioPharm (Holdings) PLC

TC BioPharm is a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the discovery, development and commercialization of gamma-delta T cell therapies for the treatment of cancer with human efficacy data in acute myeloid leukemia. Gamma-delta T cells are naturally occurring immune cells that embody properties of both the innate and adaptive immune systems and can intrinsically differentiate between healthy and diseased tissue. TC BioPharm uses an allogeneic approach in both unmodified and CAR modified gamma-delta T cells to effectively identify, target and eradicate both liquid and solid tumors in cancer.

TC BioPharm is the leader in developing gamma-delta T cell therapies, and the first company to conduct phase II/pivotal clinical studies in oncology. The Company is conducting two investigator-initiated clinical trials for its unmodified gamma-delta T cell product line - Phase 2b/3 pivotal trial for OmnImmune® in treatment of acute myeloid leukemia using the Company's proprietary allogenic CryoTC technology to provide frozen product to clinics worldwide. TC BioPharm also maintains a robust pipeline for future indications in solid tumors as well as a significant IP/patent portfolio in the use of CARs with gamma-delta T cells and owns our manufacturing facility to maintain cost and product quality controls.

Forward Looking Statements

This press release may contain statements of a forward-looking nature relating to future events. These forward-looking statements are subject to the inherent uncertainties in predicting future results and conditions. These statements reflect our current beliefs, and a number of important factors could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in this press release. We undertake no obligation to revise or update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. The reference to the website of TC BioPharm has been provided as a convenience, and the information contained on such website is not incorporated by reference into this press release.

Company Codes: NASDAQ-NMS:TCBP

Cell TherapyExecutive Change

100 Deals associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Smith & Nephew, Inc. (Tennessee)

Login to view more data

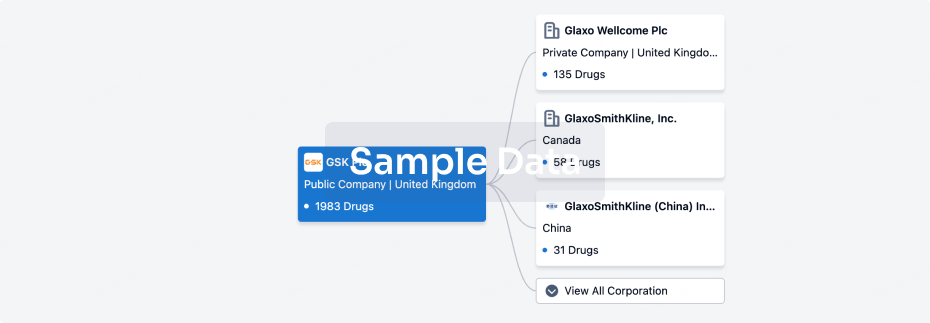

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 13 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Approved

2

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Collagenase(Advance Biofactures Corp.) ( Collagen ) | Skin Ulcer More | Approved |

Becaplermin ( PDGFRβ ) | Diabetic neuropathic ulcer More | Approved |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

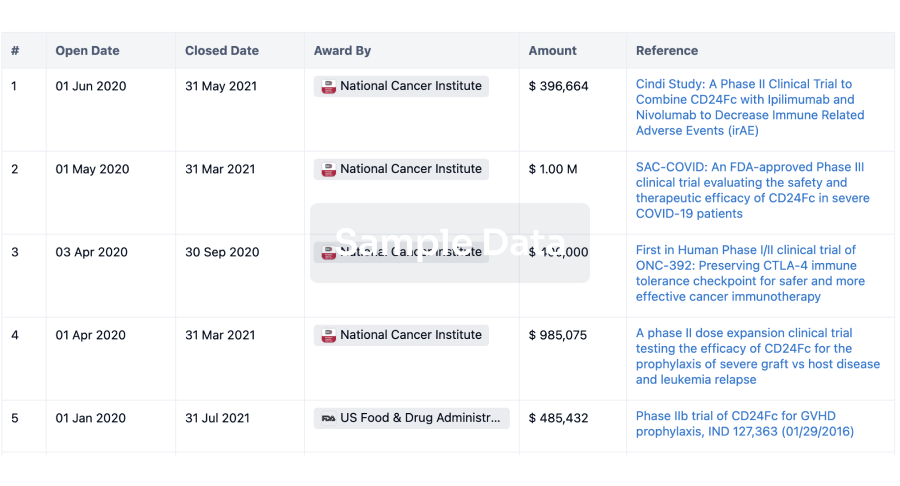

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free