Request Demo

Last update 06 Dec 2025

Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.

Last update 06 Dec 2025

Overview

Tags

Digestive System Disorders

Infectious Diseases

Neoplasms

Small molecule drug

siRNA

ASO

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Infectious Diseases | 24 |

| Neoplasms | 9 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 14 |

| siRNA | 7 |

| ASO | 6 |

| Chemical drugs | 4 |

| Oligonucleotide | 2 |

Related

34

Drugs associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.Target |

Mechanism THR-β agonists |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitors |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 1 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism HBV capsid inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

14

Clinical Trials associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.NCT06963710

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled Multicenter Phase 2 Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of ALG-000184 Compared With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate in Untreated HBeAg-Positive and HBeAg-Negative Adult Subjects With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection (B-SUPREME)

This is a Phase 2 study to evaluate efficacy and safety of 48 weeks of oral once daily monotherapy with ALG-000184 versus tenofovir disproxil fumarate (TDF) for chronic HBV infection.

Start Date15 Jul 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06959888

A Phase 1 Study in Healthy Volunteers to Evaluate the Relative Bioavailability of ALG-055009 Formulations

This is a phase 1 single dose, open-label, randomized, two-period, two-sequence, crossover study of ALG-055009 conducted in 1 cohort of healthy volunteers. The primary purpose of this study is to compare the single-dose pharmacokinetics of the 0.7 mg dose level of 2 types of soft gelatin capsule formulations of ALG-055009, Formulation 1 and Formulation 2, in approximately 8 healthy volunteers.

Start Date25 Mar 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06698549

A Phase 1 Non-Randomized, Open-Label, Multiple Dose Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics, Safety and Tolerability of ALG-097558 in Subjects With Renal Impairment and in Healthy Subjects With Normal Renal Function

This is a Phase 1 non-randomized, open-label, multiple dose, parallel-group study of ALG-097558 in subjects with severe renal impairment and subjects without renal impairment, matched for age, body weight and, to the extent possible, for gender. The primary purpose of this study is to characterize the effect of renal impairment on the plasma pharmacokinetics of ALG-097558 following administration of multiple, twice daily (Q12H) oral (PO) doses.

Start Date01 Feb 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

20

Literatures (Medical) associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.01 Aug 2025·ANTIVIRAL RESEARCH

Antisense oligonucleotides as drugs with both direct and indirect antiviral actions

Review

Author: Rajwanshi, Vivek K ; Hong, Jin

In this review, we provide a historical and current guide of recent advances in the development of ASOs either targeting viruses directly, or indirectly through modulation of host factors. Although preclinical and discovery assets are mentioned in this review, more extensive coverage is given to clinical stage assets. Most of these clinical assets are currently concentrated in the fight to eradicate hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Progresses have also been made in extrahepatic delivery of oligonucleotides and the possibility of treating respiratory virus infections in lungs with ASOs would be feasible.

10 Jul 2025·JOURNAL OF MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY

Discovery and Preclinical Profile of ALG-097558, a Pan-Coronavirus 3CLpro Inhibitor

Article

Author: Stoycheva, Antitsa D. ; Beigelman, Leonid ; Chang, Sandra ; Chanda, Sushmita ; Smith, David B. ; De Jonghe, Steven ; Serebryany, Vladimir ; Hu, Haiyang ; Jekle, Andreas ; Wuyts, Jurgen ; Laporte, Manon ; Liu, Cheng ; Ren, Suping ; Le, Kha ; Zhang, Peng ; Vandyck, Koen ; Baloju, Vamshi ; Jochmans, Dirk ; Welch, Michael ; Chaltin, Patrick ; Marchand, Arnaud ; Deval, Jerome ; Maskos, Klaus ; Leyssen, Pieter ; Neyts, Johan ; Abdelnabi, Rana ; Boland, Sandro ; Raboisson, Pierre ; Lin, Tse-I ; Tauchert, Marcel J. ; Anugu, Sreenivasa ; McGowan, David C. ; Bardiot, Dorothée ; Blatt, Lawrence ; Deta, Kiran ; Symons, Julian A. ; Jaisinghani, Ruchika ; Gupta, Kusum ; Stevens, Sarah ; Faucher, Marine O.

The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak of 2019 had a devastating impact on global health and economies worldwide. The viral cysteine protease (3CLpro) is responsible for viral polypeptide bond cleavages and is therefore an essential target to inhibit viral replication. Here, we report the discovery of an orally available, reversible covalent inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease that is also highly active across other human coronaviruses and demonstrated oral efficacy in a Syrian hamster infection model at low plasma concentrations. Projection of pharmacokinetics (PK) in humans, based on PK studies in preclinical species and enhanced in vitro/in vivo efficacy of ALG-097558 (7) indicated the potential for BID dosing without the need for ritonavir, the PK boosting component of Paxlovid. After preclinical safety and pharmacological studies, ALG-097558 has progressed to phase 1 clinical trials.

01 Jun 2025·Nucleic Acid Therapeutics

Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Testing Strategies for Oligonucleotides: A Workshop Proceedings

Review

Author: White, Tacey ; Hoberman, Alan ; Chen, Connie L. ; Coder, Pragati S. ; Kim, Tae-Won ; Maki, Kazushige ; Bender, Sara M. ; Blasi, Eileen ; Matsumoto, Mineo ; Powles-Glover, Nicola ; Siezen, Christine ; Misner, Dinah L. ; Saffarini, Camelia ; Cavagnaro, Joy A. ; Mueller, Lutz ; Duijndam, Britt ; Leconte, Isabelle ; Rayhon, Stephanie ; Mikashima, Fumito ; Bowman, Christopher J. ; Hannas, Bethany R. ; Wange, Ronald L. ; Templin, Michael V. ; Sisler, Jennifer

A 2023 workshop brought together stakeholders involved in the development and safety assessment of oligonucleotide (ONT) therapeutics. The purpose was to discuss potential strategies and opportunities for enhancing developmental and reproductive toxicity (DART) assessment of ONTs. The workshop was timely, bringing together regulators, industry representatives, consultants, and contract research organization partners interested in the ongoing development of internationally harmonized guidance for nonclinical safety assessment of ONTs. Given DART's importance in nonclinical safety assessment and the unique attributes of ONTs, the forum discussed case studies, consensus approaches, and areas needing further development to optimize DART strategies. This report covers the workshop proceedings, highlighting methods to achieve a robust DART assessment for ONTs. It includes case studies that described strategies for dose level selection, dosing frequency, species selection, and alternative animal model approaches. Topics also cover surrogate ONT use, exposure of the placenta and embryo/fetal compartment, and weight of evidence approaches. A goal of these workshop proceedings is to describe example approaches to hopefully inform the DART strategy expectations in the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidance currently under development for nonclinical safety assessment of ONTs.

155

News (Medical) associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.10 Nov 2025

Oral presentation of 96-week treatment and post-treatment data suggest best-in-class potential of pevifoscorvir sodiumSOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif., Nov. 10, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Aligos Therapeutics, Inc. (Nasdaq: ALGS), a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company focused on improving patient outcomes through best-in-class therapies for liver and viral diseases, today announced positive data from eight presentations, including one oral presentation, at the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s (AASLD) The Liver Meeting® 2025, being held November 7 – 11, 2025 in Washington, D.C. The oral and poster presentations highlighted the best-in-class potential of pevifoscorvir sodium, a potent CAM-E under development for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Pevifoscorvir Sodium Post Treatment Data Newly presented data highlight outcomes for treatment-naïve or currently not treated HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects who completed 96 weeks of 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy, followed by 8 weeks of nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) monotherapy. Among HBeAg+ subjects, 8 of 10 subjects transitioned to NA monotherapy; of these, 6 (75%) maintained HBV DNA levels below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; 10 IU/mL, target detected [TD] or target not detected [TND]) throughout the NA only 8-week follow-up period. In the HBeAg- subjects, 8 of 9 subjects switched to NA monotherapy, and all 8 (100%) subjects maintained HBV DNA < LLOQ (10 IU/mL, TD or TND) throughout the NA only 8-week follow-up period. Reductions in HBV antigen and HBV RNA were also maintained during the NA-only 8-week follow-up period. Notably, these viral biomarkers, such as HBV antigens and HBV RNA, are typically unaffected by NA therapy, suggesting that pevifoscorvir sodium may reduce the cccDNA pool through engagement of its secondary mechanism of action. Additionally, preclinical in vitro data demonstrated that ALG-001075, the active parent moiety of pevifoscorvir sodium, can prevent cccDNA formation and HBV DNA integration. This finding is further supported by cell-based studies presented at the meeting, which showed prevention of cccDNA establishment and HBV DNA integration following treatment with ALG-001075 (Poster #1251). 96 Week Pevifoscorvir Sodium Monotherapy Data Additionally, the complete 96-week data from the Phase 1 monotherapy (NCT04536337) cohorts were presented showing the continued potential of pevifoscorvir sodium to become first-line therapy for chronic suppression. In all 10 HBeAg+ subjects with very high mean baseline HBV DNA level of 8.0 log10 IU/mL, a rapid, profound, and durable HBV DNA reduction was noted following daily oral dose of 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy. At Week 48, 6 of 10 subjects (60%) achieved HBV DNA < LLOQ (10 IU/mL, TD or TND). With treatment extension, this rate increased to 10 of 10 subjects (100%) at Week 96. Additionally, HBV DNA level declined below the undetectable level (< LLOQ (TND, ≤4.29 IU/mL)) in 5 of 10 (50%) subjects at Week 96. In HBeAg- subjects receiving daily dose of 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy, all 11 (100%) had rapid decline in HBV DNA levels < LLOQ (TD or TND) by Week 24 with HBV DNA suppression maintained for up to 96 weeks of treatment; further decline in 8 of 9 (89%) subjects below the undetectable level of HBV DNA to < LLOQ (10 IU/mL, TND) was noted at Week 96. Importantly, no viral breakthrough was observed in any subjects receiving pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy for up to 96 weeks. Furthermore, concurrent multi-log10 reductions in HBV antigens (HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBcrAg) in HBeAg+ subjects and HBcrAg decline in HBeAg- subjects were observed, suggesting the potential inhibition of cccDNA establishment by CAM-E secondary mechanism of action of pevifoscorvir sodium. A favorable tolerability profile was observed in both HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects receiving 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium for up to 96 weeks. “We are pleased to present these data at this year’s The Liver Meeting, including our first oral presentation on pevifoscorvir sodium,” said Lawrence Blatt, Ph.D., M.B.A., Chairman, President, and CEO of Aligos Therapeutics. “Our results continue to demonstrate the first-in-class and best-in-class potential of pevifoscorvir sodium, with post-treatment Phase 1 data suggesting a significant impact on the cccDNA reservoir in chronic HBV infection. The sustained responses observed after transitioning to standard-of-care therapy reinforce our belief that pevifoscorvir sodium affects the entire HBV lifecycle. We look forward to sharing further data as we advance the Phase 2 B-SUPREME study. Additionally, we are encouraged by the progress of our HBV ASO program, which has shown promising preclinical results for oligonucleotide treatment of HBV infection.” Preclinical Data The preclinical posters showcased Aligos’ and its collaborators’ continued innovation and commitment to advancing next-generation therapies in the liver and viral spaces with presentations spanning novel approaches and mechanistic insights. Details of the presentations are as follows: Pevifoscorvir sodium: Potential first-/best-in-class small molecule CAM-E under investigation for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection Presentation #: 0198Type: Oral PresentationTitle: Oral Once -Daily 300 mg ALG-000184, a Novel Capsid Assembly Modulator Demonstrates potent suppression of HBV DNA in Treatment-Naive or Currently-not -treated Subjects with Chronic HBVPresenter: Professor Man-Fung Yuen, MBBS, MD, PhD, DSc, Chair and Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Hong KongDate/Time: November 9, 2025 at 5:00pm – 6:30pm ETSession: Next-generation HBV Therapeutics: Emerging Therapies and Search for Functional Cure Poster #: 1208Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Sustained Reduction of HBV Antigen Levels During the 8-Week Follow-up Period in Treatment Naïve (TN) or Currently-Not-Treated (CNT) HBeAg-Positive Subjects with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection After 96-Week 300 mg ALG-000184Presenter: Professor Man-Fung Yuen, MBBS, MD, PhD, DSc, Chair and Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Hong KongDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”) Poster #: 1251Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Capsid Assembly Modulator ALG-001075 Prevents cccDNA Formation and HBV DNA Integration In VitroPresenter: Jordi VerheyenDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”) Poster #: 1338Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Capsid Assembly Modulator ALG-001075 Binds and Directly Targets HBeAgPresenter: Jordi VerheyenDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”) Preclinical Poster #: 1248Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Differentiation of HBV capsid assembly modulators based on stabilization of core protein oligomerization and residence timePresenter: Cheng Liu, PhDDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”) Poster #: 1330Type: Poster PresentationTitle: CAM-E and CAM-A Compounds Differentially Affect Phosphorylated and Non-Phosphorylated Hepatitis B Core Protein In VitroPresenter: Rene Geissler, PhD, Abbott Diagnostics DivisionDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”) Poster #: 1155Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Lead Optimization and Selection of a Potential Best-in-Class HBV ASOPresenter: Jin Hong, PhDDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”) Poster #: 1103Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Two Pre-clinical Short Interfering RNA Molecules Targeting Human HSD17beta13 for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated SteatohepatitisPresenter: Jieun Song, PhDDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: MASLD/MASH - Experimental: Basic ("1001-1117") The presentations can be found on the Posters & Presentations section of the Aligos website (www.aligos.com) after the live event. About Aligos Aligos Therapeutics, Inc. (NASDAQ: ALGS) is a clinical stage biotechnology company founded with the mission to improve patient outcomes by developing best-in-class therapies for the treatment of liver and viral diseases. Aligos applies its science driven approach and deep R&D expertise to advance its purpose-built pipeline of therapeutics for high unmet medical needs such as chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, obesity, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), and coronaviruses. For more information, please visit www.aligos.com or follow us on LinkedIn or X. Forward-Looking Statements This press release contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Any statements in this press release that are not historical facts may be considered “forward-looking statements,” including without limitation, statements regarding Aligos’ financial results and performance as well as research and development activities, including regulatory status and the timing of announcements and updates relating to our regulatory filings and clinical trials. Such forward looking statements are subject to substantial risks and uncertainties that could cause our development programs, future results, performance, or achievements to differ materially from those anticipated in the forward-looking statements. Such risks and uncertainties include, without limitation, risks and uncertainties inherent in the drug development process, including Aligos’ clinical-stage of development, the process of designing and conducting clinical trials, the regulatory approval processes, and other matters that could affect the sufficiency of Aligos’ capital resources to fund operations. For a further description of the risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ from those anticipated in these forward-looking statements, as well as risks relating to the business of Aligos in general, see Aligos’ Quarterly Report on Form 10-Q filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on November 6, 2025 and its future periodic reports to be filed or submitted with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Except as required by law, Aligos undertakes no obligation to update any forward-looking statements to reflect new information, events or circumstances, or to reflect the occurrence of unanticipated events. Investor ContactAligos Therapeutics, Inc.Jordyn TaraziVice President, Investor Relations & Corporate Communications+1 (650) 910-0427jtarazi@aligos.com Media ContactInizio EvokeJake RobisonVice PresidentJake.Robison@inizioevoke.com

Clinical ResultPhase 1Phase 2

10 Nov 2025

SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif., Nov. 10, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Aligos Therapeutics, Inc. (Nasdaq: ALGS), a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company focused on improving patient outcomes through best-in-class therapies for liver and viral diseases, today announced positive data from eight presentations, including one oral presentation, at the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s (AASLD) The Liver Meeting® 2025, being held November 7 – 11, 2025 in Washington, D.C.

The oral and poster presentations highlighted the best-in-class potential of pevifoscorvir sodium, a potent CAM-E under development for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

Pevifoscorvir Sodium Post Treatment Data

Newly presented data highlight outcomes for treatment-naïve or currently not treated HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects who completed 96 weeks of 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy, followed by 8 weeks of nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) monotherapy. Among HBeAg+ subjects, 8 of 10 subjects transitioned to NA monotherapy; of these, 6 (75%) maintained HBV DNA levels below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; 10 IU/mL, target detected [TD] or target not detected [TND]) throughout the NA only 8-week follow-up period. In the HBeAg- subjects, 8 of 9 subjects switched to NA monotherapy, and all 8 (100%) subjects maintained HBV DNA < LLOQ (10 IU/mL, TD or TND) throughout the NA only 8-week follow-up period. Reductions in HBV antigen and HBV RNA were also maintained during the NA-only 8-week follow-up period. Notably, these viral biomarkers, such as HBV antigens and HBV RNA, are typically unaffected by NA therapy, suggesting that pevifoscorvir sodium may reduce the cccDNA pool through engagement of its secondary mechanism of action.

Additionally, preclinical in vitro data demonstrated that ALG-001075, the active parent moiety of pevifoscorvir sodium, can prevent cccDNA formation and HBV DNA integration. This finding is further supported by cell-based studies presented at the meeting, which showed prevention of cccDNA establishment and HBV DNA integration following treatment with ALG-001075 (Poster #1251).

96 Week Pevifoscorvir Sodium Monotherapy Data

Additionally, the complete 96-week data from the Phase 1 monotherapy (NCT04536337) cohorts were presented showing the continued potential of pevifoscorvir sodium to become first-line therapy for chronic suppression.

In all 10 HBeAg+ subjects with very high mean baseline HBV DNA level of 8.0 log10 IU/mL, a rapid, profound, and durable HBV DNA reduction was noted following daily oral dose of 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy. At Week 48, 6 of 10 subjects (60%) achieved HBV DNA < LLOQ (10 IU/mL, TD or TND). With treatment extension, this rate increased to 10 of 10 subjects (100%) at Week 96. Additionally, HBV DNA level declined below the undetectable level (< LLOQ (TND, ≤4.29 IU/mL)) in 5 of 10 (50%) subjects at Week 96.

In HBeAg- subjects receiving daily dose of 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy, all 11 (100%) had rapid decline in HBV DNA levels < LLOQ (TD or TND) by Week 24 with HBV DNA suppression maintained for up to 96 weeks of treatment; further decline in 8 of 9 (89%) subjects below the undetectable level of HBV DNA to < LLOQ (10 IU/mL, TND) was noted at Week 96.

Importantly, no viral breakthrough was observed in any subjects receiving pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy for up to 96 weeks. Furthermore, concurrent multi-log10 reductions in HBV antigens (HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBcrAg) in HBeAg+ subjects and HBcrAg decline in HBeAg- subjects were observed, suggesting the potential inhibition of cccDNA establishment by CAM-E secondary mechanism of action of pevifoscorvir sodium. A favorable tolerability profile was observed in both HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects receiving 300 mg pevifoscorvir sodium for up to 96 weeks.

“We are pleased to present these data at this year’s The Liver Meeting, including our first oral presentation on pevifoscorvir sodium,” said Lawrence Blatt, Ph.D., M.B.A., Chairman, President, and CEO of Aligos Therapeutics. “Our results continue to demonstrate the first-in-class and best-in-class potential of pevifoscorvir sodium, with post-treatment Phase 1 data suggesting a significant impact on the cccDNA reservoir in chronic HBV infection. The sustained responses observed after transitioning to standard-of-care therapy reinforce our belief that pevifoscorvir sodium affects the entire HBV lifecycle. We look forward to sharing further data as we advance the Phase 2 B-SUPREME study. Additionally, we are encouraged by the progress of our HBV ASO program, which has shown promising preclinical results for oligonucleotide treatment of HBV infection.”

Preclinical Data

The preclinical posters showcased Aligos’ and its collaborators’ continued innovation and commitment to advancing next-generation therapies in the liver and viral spaces with presentations spanning novel approaches and mechanistic insights.

Details of the presentations are as follows:

Pevifoscorvir sodium: Potential first-/best-in-class small molecule CAM-E under investigation for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection

Presentation #: 0198Type: Oral PresentationTitle: Oral Once -Daily 300 mg ALG-000184, a Novel Capsid Assembly Modulator Demonstrates potent suppression of HBV DNA in Treatment-Naive or Currently-not -treated Subjects with Chronic HBVPresenter: Professor Man-Fung Yuen, MBBS, MD, PhD, DSc, Chair and Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Hong KongDate/Time: November 9, 2025 at 5:00pm – 6:30pm ETSession: Next-generation HBV Therapeutics: Emerging Therapies and Search for Functional Cure

Poster #: 1208Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Sustained Reduction of HBV Antigen Levels During the 8-Week Follow-up Period in Treatment Naïve (TN) or Currently-Not-Treated (CNT) HBeAg-Positive Subjects with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection After 96-Week 300 mg ALG-000184Presenter: Professor Man-Fung Yuen, MBBS, MD, PhD, DSc, Chair and Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Hong KongDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”)

Poster #: 1251Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Capsid Assembly Modulator ALG-001075 Prevents cccDNA Formation and HBV DNA Integration In VitroPresenter: Jordi VerheyenDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”)

Poster #: 1338Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Capsid Assembly Modulator ALG-001075 Binds and Directly Targets HBeAgPresenter: Jordi VerheyenDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”)

Preclinical

Poster #: 1248Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Differentiation of HBV capsid assembly modulators based on stabilization of core protein oligomerization and residence timePresenter: Cheng Liu, PhDDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”)

Poster #: 1330Type: Poster PresentationTitle: CAM-E and CAM-A Compounds Differentially Affect Phosphorylated and Non-Phosphorylated Hepatitis B Core Protein In VitroPresenter: Rene Geissler, PhD, Abbott Diagnostics DivisionDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”)

Poster #: 1155Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Lead Optimization and Selection of a Potential Best-in-Class HBV ASOPresenter: Jin Hong, PhDDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: Hepatitis B (“1118-1367”)

Poster #: 1103Type: Poster PresentationTitle: Two Pre-clinical Short Interfering RNA Molecules Targeting Human HSD17beta13 for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated SteatohepatitisPresenter: Jieun Song, PhDDate/Time: November 7, 2025 at 8:00am – 5:00pm ETSession: MASLD/MASH - Experimental: Basic ("1001-1117")

The presentations can be found on the Posters & Presentations section of the Aligos website (www.aligos.com) after the live event.

About Aligos

Aligos Therapeutics, Inc. (NASDAQ: ALGS) is a clinical stage biotechnology company founded with the mission to improve patient outcomes by developing best-in-class therapies for the treatment of liver and viral diseases. Aligos applies its science driven approach and deep R&D expertise to advance its purpose-built pipeline of therapeutics for high unmet medical needs such as chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, obesity, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), and coronaviruses.

For more information, please visit www.aligos.com or follow us on LinkedIn or X.

Forward-Looking Statements

This press release contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Any statements in this press release that are not historical facts may be considered “forward-looking statements,” including without limitation, statements regarding Aligos’ financial results and performance as well as research and development activities, including regulatory status and the timing of announcements and updates relating to our regulatory filings and clinical trials. Such forward looking statements are subject to substantial risks and uncertainties that could cause our development programs, future results, performance, or achievements to differ materially from those anticipated in the forward-looking statements. Such risks and uncertainties include, without limitation, risks and uncertainties inherent in the drug development process, including Aligos’ clinical-stage of development, the process of designing and conducting clinical trials, the regulatory approval processes, and other matters that could affect the sufficiency of Aligos’ capital resources to fund operations. For a further description of the risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ from those anticipated in these forward-looking statements, as well as risks relating to the business of Aligos in general, see Aligos’ Quarterly Report on Form 10-Q filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on November 6, 2025 and its future periodic reports to be filed or submitted with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Except as required by law, Aligos undertakes no obligation to update any forward-looking statements to reflect new information, events or circumstances, or to reflect the occurrence of unanticipated events.

Investor ContactAligos Therapeutics, Inc.Jordyn TaraziVice President, Investor Relations & Corporate Communications+1 (650) 910-0427jtarazi@aligos.com

Media ContactInizio EvokeJake RobisonVice PresidentJake.Robison@inizioevoke.com

Clinical ResultPhase 2Phase 1

06 Nov 2025

SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif., Nov. 06, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Aligos Therapeutics, Inc. (Nasdaq: ALGS, “Aligos”), a clinical stage biotechnology company focused on improving patient outcomes through best-in-class therapies for liver and viral diseases, today reported recent business progress and financial results for the third quarter 2025.

“Our Phase 2 B-SUPREME study of pevifoscorvir sodium (pevy) is enrolling nicely, with subjects dosed across a number of countries, including the U.S., China, Hong Kong, and Canada,” stated Lawrence Blatt, Ph.D., M.B.A., Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer of Aligos Therapeutics. “We are pleased with the progress to date and look forward to interim readouts in 2026. Importantly, we look forward to sharing additional pevy data next week at AASLD’s The Liver Meeting®. We maintain our enthusiasm regarding the potential for pevy as well as our entire development pipeline, including ALG-055009, which is in continued discussions with potential partners for obesity and MASH.”

Recent Business Progress

Pipeline Updates

Pevifoscorvir sodium: Potential first-/best-in-class small molecule CAM-E for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection

The Phase 2 B-SUPREME study (NCT06963710) of pevifoscorvir sodium in subjects with chronic HBV infection dosed its first patient in August 2025. The study is designed as a randomized, double-blind, active-controlled multicenter study evaluating the safety and efficacy of pevifoscorvir sodium monotherapy compared with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in approximately 200 untreated HBeAg+ or HBeAg- adult subjects with chronic HBV infection for 48 weeks. The primary endpoint in the HBeAg+ subjects is HBV DNA

Phase 1Phase 2Financial Statement

100 Deals associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Aligos Therapeutics, Inc.

Login to view more data

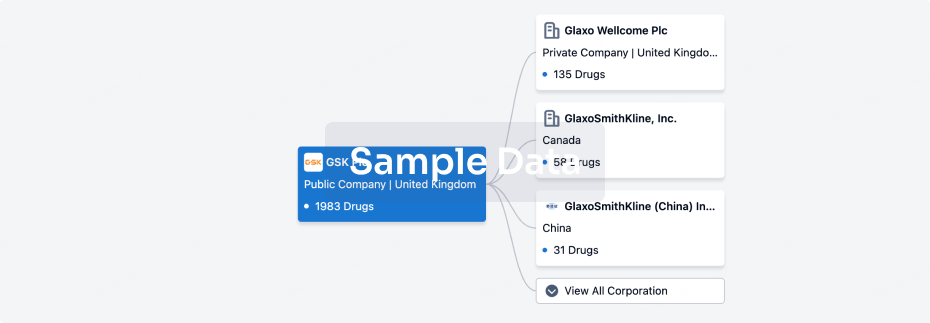

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 23 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

2

28

Preclinical

Phase 1

2

2

Phase 2

Other

16

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Pevifoscorvir sodium ( HBV capsid ) | Hepatitis B, Chronic More | Phase 2 |

ALG-055009 ( THR-β ) | Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatohepatitis More | Phase 2 |

ALG-010133 ( L-HBsAg ) | Hepatitis B, Chronic More | Phase 1 |

ALG-097558 ( SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro ) | COVID-19 More | Phase 1 |

ALG-093702 ( PDL1 ) | Hepatocellular Carcinoma More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

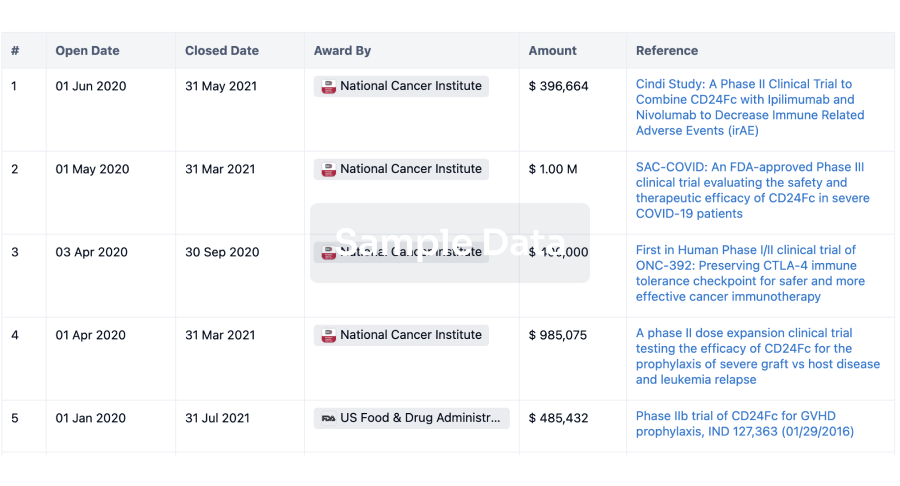

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free