Request Demo

Last update 01 Nov 2024

Action For Children

Last update 01 Nov 2024

Overview

Related

1

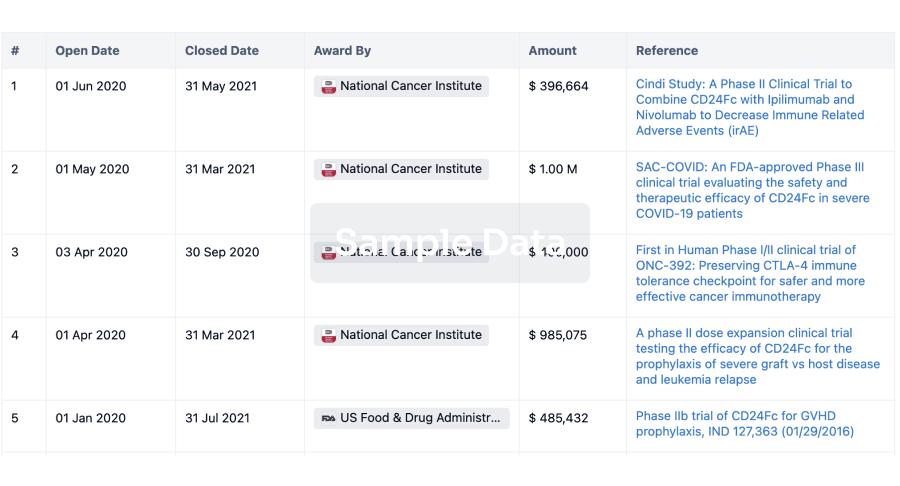

Clinical Trials associated with Action For ChildrenNCT05194020

All in Dads! Program Evaluation

The purpose of this study is to help fathers establish and strengthen their relationship with their children and the mothers of their children; to reduce domestic violence in vulnerable families; to improve economic stability of fathers through comprehensive, job-driven career services; to employ intensive case management barrier removal, individual job coaching, and comprehensive family development to improve short and long-term outcomes.

Start Date01 Apr 2021 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Action For Children

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Action For Children

Login to view more data

6

Literatures (Medical) associated with Action For Children01 Jul 2013·Early Years Educator

Investing in quality is only option

Author: Tickell, Dame Clare

Action on Neglect - a resource pack

Author: Erica Whitfield ; Julie Taylor ; Brigid Daniel ; Cheryl Burgess ; David Derbyshire

Family Group Conferencing: A Promising Practice in the Context of Early Intervention in Northern Ireland

Author: Michael Hoy ; Paul Kellagher ; David Hayes

49

News (Medical) associated with Action For Children11 Dec 2022

Data demonstrate that a non-viral, liver-directed gene therapy utilizing Super piggyBac® (SPB) DNA Modification System achieved and maintained normalized human FVIII (hFVIII) activity following a single dose

Data establishes preclinical proof of principle for treatment of Hemophilia A across all ages, which could potentially lead to a functional cure

SAN DIEGO, Dec. 11, 2022 /PRNewswire/ -- Poseida Therapeutics, Inc. (Nasdaq: PSTX), a clinical-stage cell and gene therapy company advancing a new class of treatments for patients with cancer and rare diseases, today announced that the Company will present preclinical data from its P-FVIII-101 gene therapy program, partnered with Takeda, at the 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting being held in New Orleans and virtually December 10–13, 2022. The data establish preclinical proof of principle for the treatment of Hemophilia A using P-FVIII-101, a non-viral liver-directed gene therapy utilizing Poseida's Super piggyBac delivery system, which could potentially lead to a functional cure.

"We are very excited by these new P-FVIII-101 data, which demonstrate normalization of FVIII levels in an animal model of Hemophilia A," said Brent Warner, President, Gene Therapy at Poseida Therapeutics. "Most importantly, we have demonstrated the use of a fully non-viral gene therapy to address the underlying cause of Hemophilia A, providing key preclinical proof of principle for our program. We look forward to our continued work on this program together with our partner, Takeda."

Details of the oral presentation are as follows:

Title: Sustained Factor VIII Activity Following Single Dose of Non-Viral Integrating Gene Therapy

Presenter: Brian Truong, Ph.D.

Presentation Date and Time: Today, December 11, 2022 at 10:15 AM CT

Session Name: 321. Coagulation and Fibrinolysis: Basic and Translational

Publication Number: 400

Location: Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, 293-294

P-FVIII-101 utilizes the Company's non-viral, nanoparticle-based delivery system together with SPB, which enables increased transgene cargo capacity, stable integration into the genome, potential for re-dosing, and potentially simpler manufacturing processes. The data to be presented show that P-FVIII-101 achieved and sustained normalized (>50%) hFVIII activity following a single dose and delivered therapeutic FVIII activity in mice following single and repeat doses, indicating the potential for dose titration. Durable responses were observed following a single dose reported over the study period of seven months. The data support that with SPB the therapeutic transgene expression cassette can be stably integrated into the genome of liver cells and provide consistent and durable therapeutic activity.

"Although gene therapy has the potential to deliver functional cures for Hemophilia A, current approaches face challenges – both with durability and the ability to re-dose – and are not appropriate for use in juvenile patients," said Denise Sabatino, Ph.D., Research Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and an author on the oral presentation. "The data being presented today show that P-FVIII-101 has the potential to correct a deficiency in FVIII to near normal levels in juvenile mice, providing a path forward for a more tolerable, durable treatment for Hemophilia A in pediatric patients. Current treatment options are not curative and require lifelong treatment, and P-FVIII-101 may have the potential to significantly improve outcomes for people with Hemophilia A."

In October 2021, Poseida announced that it had entered into a research collaboration and exclusive license agreement with Takeda to utilize the Company's proprietary genetic engineering platform technologies for the research and development of gene therapies, including P-FVIII-101. The companies plan to continue preclinical studies to advance the program toward an Investigational New Drug (IND) application.

About P-FVIII-101

P-FVIII-101 is a liver-directed gene therapy partnered with Takeda combining Poseida's Super piggyBac platform and nanoparticle delivery technologies for the in vivo treatment of Hemophilia A. Hemophilia A is a bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency in Factor VIII production with a high unmet need. P-FVIII-101 utilizes the piggyBac gene integration system delivered via lipid nanoparticle, which has demonstrated stable and sustained Factor VIII expression in animal models.

About Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

Poseida Therapeutics is a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company advancing differentiated cell and gene therapies with the capacity to cure certain cancers and rare diseases. The Company's pipeline includes allogeneic CAR-T cell therapy product candidates for both solid and liquid tumors as well as in vivo gene therapy product candidates that address patient populations with high unmet medical need. Poseida's approach to cell and gene therapies is based on its proprietary genetic editing platforms, including its non-viral Super piggyBac® DNA Delivery System, Cas-CLOVER™ Site-Specific Gene Editing System and nanoparticle and hybrid gene delivery technologies. The Company has formed global strategic collaborations with Roche and Takeda to unlock the promise of cell and gene therapies for patients. Learn more at and connect with Poseida on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Forward-Looking Statements

Statements contained in this press release regarding matters that are not historical facts are "forward-looking statements" within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Such forward-looking statements include statements regarding, among other things, expected plans with respect to clinical trials; the potential benefits of Poseida's technology platforms and product candidates; and Poseida's plans and strategy with respect to developing its technologies and product candidates. Because such statements are subject to risks and uncertainties, actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements are based upon Poseida's current expectations and involve assumptions that may never materialize or may prove to be incorrect. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in such forward-looking statements as a result of various risks and uncertainties, which include, without limitation, Poseida's reliance on third parties for various aspects of its business; risks and uncertainties associated with development and regulatory approval of novel product candidates in the biopharmaceutical industry; Poseida's ability to retain key scientific or management personnel; and the other risks described in Poseida's filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. All forward-looking statements contained in this press release speak only as of the date on which they were made. Poseida undertakes no obligation to update such statements to reflect events that occur or circumstances that exist after the date on which they were made, except as required by law.

SOURCE Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

License out/inGene TherapyASHClinical ResultClinical Study

10 Dec 2022

Scientists present on novel therapeutic approaches and new treatment paradigms

NEW ORLEANS, La., Dec. 10, 2022 /PRNewswire/ -- New research being presented at the 64th American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition focuses on a variety of approaches for several hematologic diseases to improve outcomes and quality care.

"These studies represent a potpourri of novel approaches and new drug targets across classical hematology, malignant disease, and genetic disorders," said press briefing moderator

Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and former president of ASH. "These are all exciting advances and give a glimpse into the incredible breadth and scope of research inquiries to find better treatments and even cures, especially for patients who are heavily pre-treated and don't have a lot of other treatment options."

The first study shows additional disease control and promising response rates for individuals with treatment-refractory multiple myeloma by adding an immunotherapy that has a different target than existing therapies.

In the second study, researchers report that more than half of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), a rare chronic disorder that causes dangerously low platelet levels, treated with efgartigimod experienced improvements in their platelet count, cutting the risk of dangerous bleeding. According to Dr. Lee, the drug's novel mechanism may be generalizable to other diseases.

The third study finds that people with beta thalassemia who received one-time gene therapy were free of burdensome transfusions and had marked improvements in their quality of life. "These long-term data show that this approach could be a curative, one-time therapy for patients," Dr. Lee said.

The fourth study, which looked at the cost-effectiveness of gene therapy for sickle cell disease (SCD) using innovative modeling that adjusts for health inequities, suggests that gene therapy could be an equitable therapeutic strategy for all people with SCD.

Of course, the drugs studied will be costly, so the question of their implementation into practice and equity in terms of access will need to be addressed, Dr. Lee added.

The press briefing will take place on Saturday, December 10, at 10:30 a.m. Central time in press briefing room 346, Ernest N. Morial Convention Center.

Talquetamab Generates High Response Rate in Patients with Hard-to-treat Multiple Myeloma

157: Talquetamab, a G Protein-Coupled Receptor Family C Group 5 Member D x CD3 Bispecific Antibody, in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM): Phase 1/2 Results from MonumenTAL-1

In an early-phase trial, nearly three-quarters of patients who received talquetamab, a first-in-class experimental immunotherapy for multiple myeloma, saw a significant reduction in cancer burden within a few months. The study participants had all been previously treated with at least three different therapies without achieving lasting remission, suggesting talquetamab could offer new hope for patients with hard-to-treat multiple myeloma.

"This means that three-quarters of these patients are looking at a new lease on life," said

Ajai Chari, MD, of The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai in New York. "We're hoping that this will soon become available so that patients can benefit."

Talquetamab binds to both T cells and multiple myeloma cells. This activates an immune response to destroy myeloma cells by bringing T cells to the cancer, a strategy that researchers described as "bringing your army to the enemy." It also uses a different target than other approved therapies; in this case, the target is a receptor expressed on the surface of cancer cells known as GPRC5D.

Multiple myeloma is a blood cancer that forms in plasma cells. Several treatments are available, but the prognosis can be very poor and many patients survive less than a year if the disease doesn't respond to therapy or returns after several different treatments.

The study enrolled a total of 288 patients who were unable to tolerate existing therapies or showed disease progression after at least three multiple myeloma therapies. After an initial phase generated encouraging results in terms of safety and efficacy, researchers began enrolling additional patients to assess the agent's efficacy with two different dosing regimens—0.4 mg/kg weekly and 0.8 mg/kg every other week. Data from patients who had received these same dosing regimens in the first phase were included in the analysis for the second phase.

Seventy-four percent of those receiving 0.4 mg/kg of talquetamab weekly and 73% of those receiving 0.8 mg/kg every other week saw a measurable improvement of their cancer following treatment, the primary endpoint for the trial's second phase. More than 30% of patients in both groups had a complete response (no detection of myeloma-specific markers) or better and nearly 60% had a "very good partial response" or better (indicating the cancer was substantially reduced but not necessarily down to zero). The median time to a measurable response was approximately 1.2 months in both dosing groups and the median duration of response is 9.3 months to date with weekly dosing. Researchers are continuing to collect data on the duration of response in the group receiving 0.8 mg/kg every other week and for patients in both dosing groups who had a complete response or better.

Side effects were relatively frequent, but typically mild. About three-quarters of patients experienced cytokine release syndrome (a sign of immune activation common with therapies that redirect T cells, typically causing a fever); 60% experienced skin-related side effects such as rash; about half reported taste changes; and about half reported nail disorders. Researchers said 5-6% of patients stopped talquetamab treatment early due to side effects.

The response rate observed in this cohort, which Dr. Chari explained is higher than that of most currently accessible therapies, suggests talquetamab could offer a viable option for patients with hard-to-treat myeloma, offering a chance to extend patient lifespans.

In a separate cohort, 51 patients who had previously received therapies that redirect T cells showed a response to talquetamab. In addition, several other studies are underway to assess the use of talquetamab in combination with other existing and investigational multiple myeloma therapies, which could allow patients to have similar or improved benefits, potentially in earlier stages of treatment.

This study was funded by Janssen Research & Development LLC.

Ajai Chari, The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai, will present this study during an oral presentation on Saturday, December 10, 2022, at 12:00 noon in R02-R05.

Improvements in Platelet Count Observed in More Than Half of Patients with ITP Treated with Efgartigimod

3: Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Efgartigimod in Adults with Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia: Results of a Phase 3, Multicenter, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial (ADVANCE IV)

More than half of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), a rare chronic disorder that causes dangerously low platelet levels, treated with the novel agent efgartigimod (EFG) experienced improvements in their platelet count. For people with ITP, this improvement could mean less time away from work or school, fewer limitations on activities due to a risk of bleeding caused by trauma, and less worrying about spontaneous bleeding such as nosebleeds.

"This is exciting news because existing treatments fail to improve platelet counts for as many as 30% of adults with chronic ITP," said

Catherine Broome, MD, associate professor of medicine at the Georgetown Lombardi Cancer Center in Washington, DC, and the study's principal investigator. "The trial results show that the therapy was both efficacious and well tolerated."

ITP is an autoimmune disease in which the body produces immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies that bind to and increase the clearance of platelets (blood cells that help the body control bleeding) from blood circulation. Healthy people have a platelet count of between 150,000 and 400,000 per microliter of blood, whereas patients with ITP often have a platelet count of less than 50,000 per microliter and in some cases less than 20,000. Patients enrolled in this study had an average platelet count of less than 30,000 and at least two prior ITP treatments or one prior and one concurrent treatment.

ITP can be treated in a variety of ways, including with medications that suppress the immune system and decrease the production of IgG autoantibodies. Steroids are one of the most commonly used therapies, but long-term use of these medications can cause serious side effects such as weight gain, insomnia, and loss of bone density. EFG is a novel medication that reduces levels of IgG, including the autoantibodies that increase the clearance of platelets in patients with ITP.

In the ADVANCE IV study, Dr. Broome and her colleagues enrolled 131 patients in six countries. The patients' average age was 50, and 54% were women. The mean time since their ITP diagnosis was about 10 years, and two-thirds had received three or more previous ITP therapies that had either not worked or had caused intolerable side effects. Study participants were randomly assigned to receive intravenous infusions of either EFG or a placebo for 24 weeks; two thirds received EFG and one third the placebo. Infusions were given weekly for four weeks; after that, depending on response, some patients switched to getting an infusion every two weeks. The study was double blinded, meaning that neither the patients nor their doctors knew who was receiving EFG versus the placebo.

The study's primary endpoint was the number of participants who maintained a platelet level of more than 50,000 per microliter during weeks 19 through 24. Secondary endpoints included, among others, the number of bleeding episodes and the proportion of participants who had sustained platelet levels above 50,000 for at least six of the final eight weeks of the study.

At 24 weeks, 21.8% of participants treated with EFG, compared with 5% of those who received a placebo, met the primary endpoint. More than half (51.2%) of patients who received EFG, compared with 20% of those in the placebo group, met internationally recognized criteria for response to ITP, which include measuring bleeding episodes in addition to platelet count.

Adverse events such as bruising, headaches, and blood in urine occurred at roughly the same frequency in both groups of patients. Serious AEs were reported in 8.1% (7/86) of participants in the EFG group and in 15.6% (7/45) in the placebo group; however, none were treatment-related. These included bleeding or events related to bleeding (n=5), infections (n=4), and worsening primary ITP (n=3).

The patients treated with EFG are now being followed for a minimum of two years in a follow-up study to continue to evaluate safety and long-term platelet response. In addition, another phase III trial is currently testing a formulation of EFG that can be injected under the skin (subcutaneously) rather than into a vein. If this formulation is shown to be effective, Dr. Broome said, it could mean that patients could administer their own injections of the medication instead of having to go to a health care facility every week or two to receive the medication intravenously.

The study was funded by argenx, which manufactures EFG.

Catherine Broome, MD, Georgetown University School of Medicine, will present this study during a plenary presentation on Sunday, December 11, 2022, at 2:00 p.m. Central time in Hall E.

Patients Undergoing Gene Therapy for Beta Thalassemia Achieve Sustained Transfusion Independence, as well as Improved Quality of Life

2348: Long Term Outcomes of 63 Patients with Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia (TDT) Followed up to 7 Years Post-Treatment with betibeglogene autotemcel (beti-cel) Gene Therapy and Exploratory Analysis of Predictors of Successful Treatment Outcomes in Phase 3 Trials

3665:Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Treatment with betibeglogene autotemcel in Patients with Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia

In an international study – the largest to date of gene addition therapy for an inherited blood disorder – more than 80% of evaluable patients with a severe genetic condition, who had been dependent on regular blood transfusions to stay alive, remained transfusion-free three years after receiving a single infusion of their own blood-forming stem cells that had been altered to correct the genetic mutation that caused their disease. A separate study that assesses patient-reported outcomes and quality of life showed marked improvements in patients' ability to work, attend school, and be physically active after gene therapy. Among patients who were attending school, absenteeism caused by beta thalassemia symptoms declined by about half.

The patients have a severe form of beta thalassemia, an inherited disease in which the body makes too little hemoglobin, the molecule that, in red blood cells, carries oxygen to the body's cells. The disease is caused by a wide array of mutations in the beta-globin gene, which carries the instructions for the body to manufacture one of the proteins that make up hemoglobin. Patients in the gene therapy study received their own blood-forming stem cells that had been genetically modified by adding one or more healthy copies of the beta-globin gene.

"The main message from our findings is that therapy to add a healthy gene to the stem cells is a valid, safe, and potentially curative treatment option for many patients with beta thalassemia," said study author

Franco Locatelli, MD, professor of pediatrics at IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, in Rome, Italy. "Gene therapy resulted not only in sustained transfusion independence, but also in improved quality of life."

In beta thalassemia, a shortage of hemoglobin leads to a shortage of healthy red blood cells, causing anemia, symptoms of which include fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, dizziness, and headaches. People with the most severe form of the disease need lifelong regular blood transfusions, an adverse effect of which is iron overload, namely an excess level of iron in the body. Over time, despite the regular use of chelation therapy to reduce iron levels, iron overload can cause severe damage to multiple organs, including the heart, liver, pancreas, and joints, leading to complications such as heart failure, cirrhosis, diabetes, and osteoarthritis.

While relatively rare in the United States, beta thalassemia is common in other parts of the world, including the eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. It affects men and women about equally, and symptoms typically appear by age two.

In the analysis of long-term outcomes, 63 patients enrolled in four consecutive studies first underwent a procedure to harvest their blood-forming stem cells. Each patient's cells were sent to a laboratory, where healthy copies of the beta-globin gene were inserted into them. The genetically modified cells were frozen, shipped back, thawed, and re-infused into patients. Before the infusion, the same patients were treated with high-dose chemotherapy to kill their remaining unhealthy stem cells.

After completing two years of follow-up, patients could enroll in a long-term study to continue follow-up for up to 13 more years. The current study reports results for patients who have been followed for up to seven years (median of 3.5 years) since they received their genetically modified stem cells.

Forty-nine patients achieved transfusion independence, which was defined in the study as not needing a transfusion of red blood cells for at least one year while maintaining a hemoglobin level greater than 9 g/dL; all of them remained transfusion independent at three years of follow-up. The percentage of evaluable patients who completed the study and achieved transfusion independence was 68% in the two initial studies and 89% in two more-recent studies that used an optimized approach to prepare the genetically modified cells.

In a separate analysis of health-related quality of life, 93.8% of patients were working or looking for work three years after receiving gene therapy, whereas 68.8% had been doing so before gene therapy. Among patients who were in school, 44.4% reported missing school due to their illness compared with 83.3% who had reported missing school before gene therapy. Eighty percent of patients reported improvement in physical activity three years after gene therapy.

Eleven patients (18%) experienced one or more adverse events that may have been related to the treatment. No patient died because of the treatment and no cancers or other severe adverse effects were recorded.

The therapy, betibeglogene autotemcel (known as beti-cel), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in August as the first cell-based gene addition therapy for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with beta-thalassemia who require regular red blood cell transfusions.

While beta thalassemia can be cured by a transplant of healthy stem cells from a matched sibling donor, this treatment option is not available to the 75% of patients who lack a matched donor, Dr. Locatelli said. "Gene therapy is potentially applicable to a much larger number of patients because they don't need to have a matched donor," he said.

These studies were funded by bluebird bio, the maker of beti-cel.

Franco Locatelli, IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, will present these studies during poster presentations on Sunday, December 11, 2022, at 6:00 p.m. and Monday, December 12, 2022, at 6:00 p.m. Central Time in Hall D.

Gene Therapy Found to Be an Equitable, Potentially Cost-Effective Option for Individuals Living with Sickle Cell Disease in the U.S.

581: Gene Therapy Equity in Sickle Cell Disease: Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (DCEA) of Gene Therapy Vs. Standard-of-Care in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease in the United States

Gene therapy can be an equitable and potentially cost-effective therapeutic option for people in the United States with SCD despite a projected per-patient cost of over $2 million for one-time treatment, according to researchers, who conducted the first study to try to answer this question using a novel approach that factors health disparities into SCD patient care.

"In the United States, SCD predominantly affects African Americans, who have historically been a very marginalized population when it comes to health care," said

George Goshua, MD, MSc, the study's principal investigator and an assistant professor of medicine at Yale University School of Medicine. "Our study shows that, when we compare the costs of gene therapy and existing standard-of-care treatment for SCD using a technique that accounts for historical health disparities, gene therapy could be an equitable therapeutic strategy for all patients with SCD, whether their disease is mild, moderate, or severe."

SCD is the most common inherited red blood cell disorder in the United States, affecting an estimated 100,000 individuals, mostly African Americans. In people with SCD, the red blood cells, which are normally round, become crescent or sickle shaped. As these cells travel through the bloodstream, they can get stuck, cutting off blood flow and causing intense pain. People with SCD suffer from an array of physical complications, including acute pain crises, joint and organ damage, stroke, and reduced life expectancy. Additionally, this population is often stigmatized due to poor understanding among health care professionals and the public of the life-limiting effects of the disease.

This study, a collaboration between the Yale University School of Medicine and The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is believed to be the first in hematology to use a technique known as distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (DCEA), which accounts for historical health disparities by adding an "equity weight" to the calculation of a treatment's cost effectiveness. An equity weight, Dr. Goshua explained, is "a way of quantifying how much we prioritize health care equity." Because this has never been studied in SCD, he and his colleagues used a range of equity weights that have been used in other DCEA studies in the United States.

The researchers factored these equity weights into their analysis of 10 years of data on the annual cost of health care for patients with SCD who had private health insurance and were receiving any of several standard therapies, such as the drug hydroxyurea, antibiotics, blood transfusions, and stem cell transplantation. They examined factors including patients' gender and how frequently they were hospitalized for an acute pain crisis.

Dr. Goshua explained that several assumptions were made: that one-time gene therapy would cost $2.1 million (based on the cost of gene therapies for other diseases that have recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration); that gene therapy would be 100% effective in achieving disease remission; and that it would be offered to all patients with SCD in the United States aged 12 and older (the age limit applied in randomized trials of gene therapy to date).

Based on these assumptions, the investigators calculated that gene therapy would result in 25.5 discounted lifetime quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) compared with 16.0 for standard therapy. (QALYs, a measure of disease burden, are widely used to assess the value of medical interventions; one QALY equates to one year in perfect health.) They concluded that gene therapy "can be an equitable therapeutic strategy for patients with SCD in the United States" at a cost of between $1.4 million and $3.0 million per patient, depending on the equity weight used.

A limitation of the study, Dr. Goshua said, is the assumption that gene therapy for SCD would be 100% effective. "We don't yet have enough long-term data on effectiveness," he said. "If gene therapy for SCD turns out to be less than 100% effective – that is, if some people who undergo gene therapy relapse and need additional treatment – the maximum cost at which gene therapy for SCD would be an equitable therapeutic strategy would decrease."

George Goshua, MD, MSc Yale University School of Medicine, will present this study during an oral presentation on Sunday, December 11, 2022, at 1:00 p.m. in R06-R09.

Additional press briefings will take place throughout the meeting on health equity, advances in blood cancer research and care, optimizing pediatric care, and selected late-breaking abstracts. For the complete annual meeting program and abstracts visit . Follow ASH and #ASH22 on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Facebook for the most up-to-date information about the 2022 ASH Annual Meeting.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) () is the world's largest professional society of hematologists dedicated to furthering the understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disorders affecting the blood. For more than 60 years, the Society has led the development of hematology as a discipline by promoting research, patient care, education, training, and advocacy in hematology. ASH's flagship journal, Blood (), is the most cited peer-reviewed publication in the field, and Blood Advances (), is the Society's online, peer-reviewed open-access journal.

SOURCE American Society of Hematology

Clinical ResultPhase 3Drug ApprovalImmunotherapy

08 Dec 2022

39 Pediatric Providers to Join Phoenix Children's Medical Group

PHOENIX, Dec. 8, 2022 /PRNewswire/ -- Phoenix Children's, one of the fastest-growing pediatric healthcare systems in the country, today announced it finalized an agreement with Valley Anesthesiology Consultants to transfer 39 of its pediatric anesthesiologists to Phoenix Children's.

"We made the strategic decision to build an integrated and aligned medical group for all areas of operations at Phoenix Children's, including anesthesiology, to best serve the growing number of patient families in our community," said Robert L. Meyer, President and CEO of Phoenix Children's. "Retaining this talented group of pediatric anesthesiologists will help ensure Phoenix Children's growing network of hospitals and ambulatory locations can continue to deliver on the excellent clinical care families have come to expect from our health system."

The 39 experienced pediatric anesthesiologists were a part of Valley Anesthesiology Consultants, a leading medical group providing anesthesiology care in Arizona. Through the health system's collaboration with Valley Anesthesiology Consultants, the anesthesiologists have practiced extensively at Phoenix Children's and will be directly employed by Phoenix Children's Medical Group starting December 1, 2022.

"We will miss the team members who have become part of our Valley family but know the health system's transition will further support the growing needs of the community and the patients we all serve," said Ian Kallmeyer, MD, FASA, president of Valley Anesthesiology Consultants. "During our longstanding relationship with Phoenix Children's, we have healed and comforted families, improved patients' access to care and advanced the delivery of quality care. Families will continue to be in good hands with the anesthesiology team providing them care when they need it most."

Since 1983, Phoenix Children's and Valley Anesthesiology Consultants have worked closely to provide the best care possible to children and their families. This includes a shared commitment to clinical best practices and improved quality of care to support the needs of pediatric patients throughout Arizona.

About Phoenix Children's

Phoenix Children's is one of the nation's largest pediatric health systems. It comprises Phoenix Children's Hospital – Thomas Campus, Phoenix Children's Hospital – East Valley at Dignity Health Mercy Gilbert Medical Center, four pediatric specialty and urgent care centers, 11 community pediatric practices, 20 outpatient clinics, two ambulatory surgery centers and seven community-service-related outpatient clinics throughout the state of Arizona. The system provides world-class inpatient, outpatient, trauma, emergency and urgent care and has been serving children and families for nearly 40 years. Phoenix Children's Care Network includes more than 1,175 pediatric primary care providers and specialists who deliver care across more than 75 subspecialties. For more information, visit phoenixchildrens.org.

SOURCE Phoenix Children's

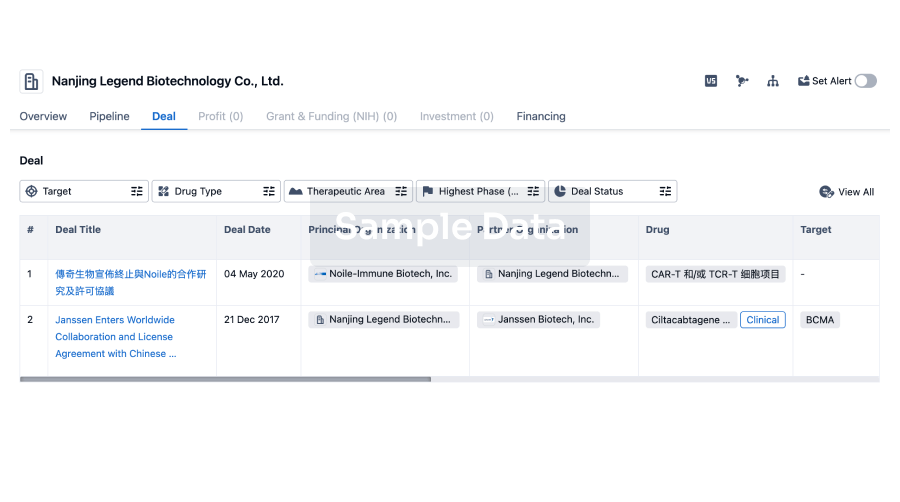

100 Deals associated with Action For Children

Login to view more data

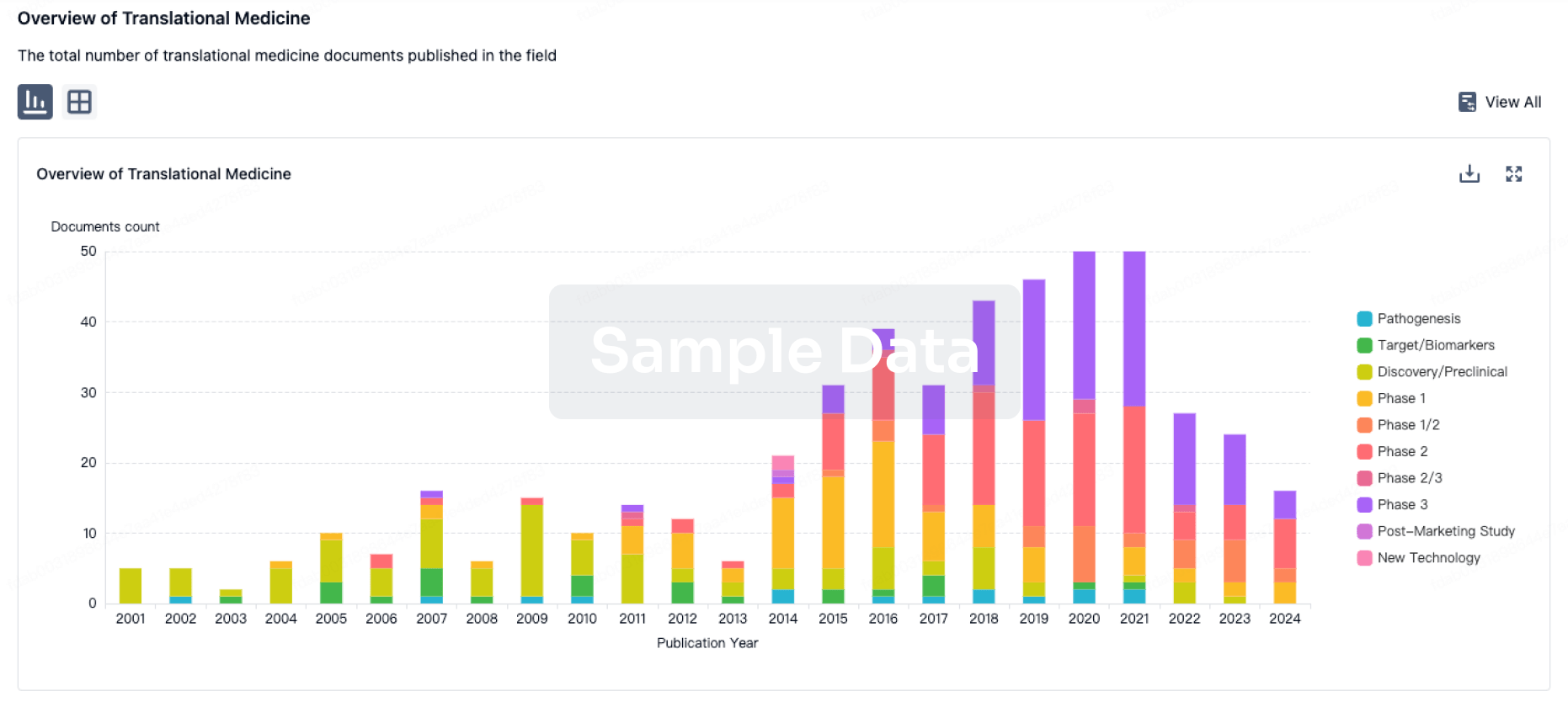

100 Translational Medicine associated with Action For Children

Login to view more data

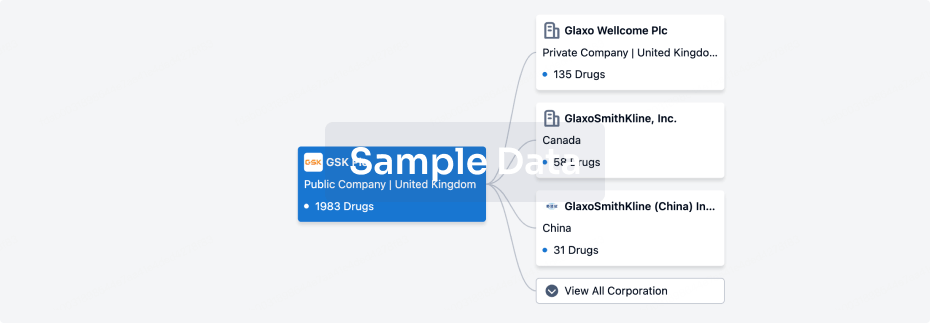

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 15 Jan 2025

No data posted

Login to keep update

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

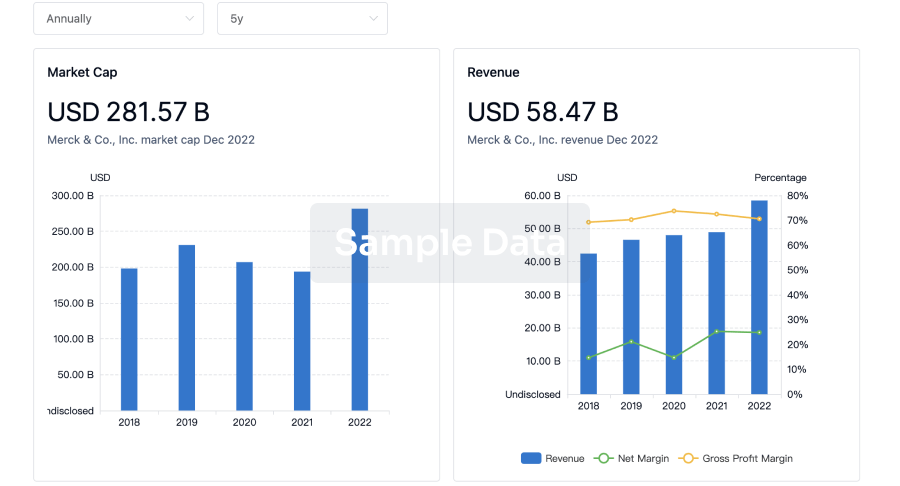

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

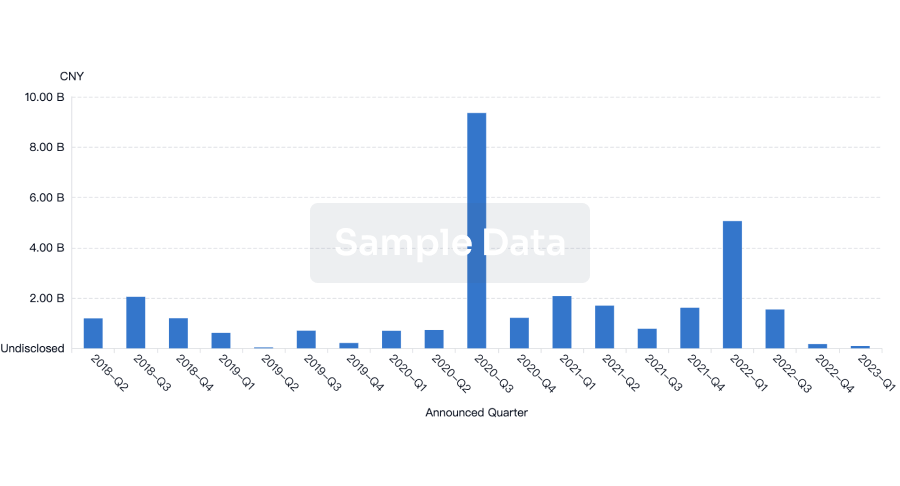

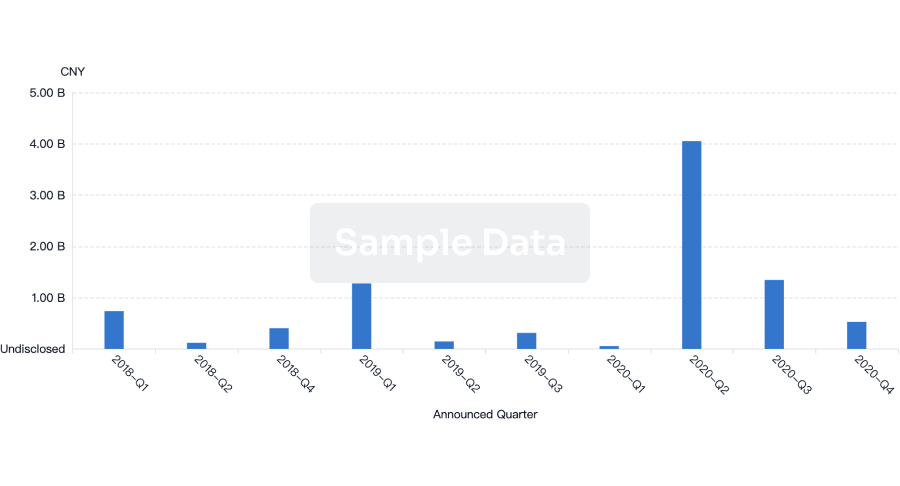

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

Chat with Hiro

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free