Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Jaguar Gene Therapy LLC

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Tags

Endocrinology and Metabolic Disease

Other Diseases

Nervous System Diseases

AAV based gene therapy

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| AAV based gene therapy | 7 |

Related

7

Drugs associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLCTarget |

Mechanism SHANK3 modulators [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 1/2 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism PAX4 modulators [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism GALT modulators [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

1

Clinical Trials associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLCNCT06662188

A Phase 1/2, Multicenter, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation, Safety, Tolerability, and Clinical Activity Study of a Single Dose of JAG201 Gene Therapy Delivered Via Intracerebroventricular Administration in Participants with SHANK3 Haploinsufficiency

This is a Phase 1/2, first in human, open-label, dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and clinical activity of a single dose of JAG201 administered via intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection in pediatric and adult participants with SHANK3 haploinsufficiency resulting from SHANK3 loss of function mutations and chromosomal deletions encompassing the SHANK3 gene. Clinical data will be evaluated for safety, tolerability, and preliminary clinical activity of JAG201 in pediatric and adult participants with SHANK3 haploinsufficiency. The pediatric cohorts will start enrolling first and the enrollment for adult cohorts may be initiated at a later timepoint in the study.

Start Date07 Jan 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLC

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLC

Login to view more data

22

News (Medical) associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLC17 Dec 2024

CHICAGO —

Over the years, a handful of cities have tried catching up to the flourishing biotech hubs in Boston or the San Francisco Bay Area. Chicago, the third-largest city in the US, is putting together its best attempt.

The growth in the Chicago-area biotech landscape is due to several reasons, including better collaboration between local research institutions, the opening of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub last year, new incubators and brand-new lab space.

“We don’t want to just compete with traditional biotech hubs,” said John Conrad, CEO of the Illinois Biotechnology Innovation Organization. “We’re really focused on redefining what a biotech ecosystem can be in the city of Chicago.”

The city ranked 10th in the US for biopharma R&D employment in 2023, with 13,080 jobs, according to a

report

from real estate firm CBRE. But it punched above its weight in biopharma manufacturing roles, ranking third nationally with 60,320 workers.

“People use the word ‘boom.’ I don’t like those types of hyperbolic statements,” said John Flavin, CEO of a biotech incubator called Portal Innovations. “If you look at the data, it would support steady growth, and I see that continuing in Chicago.”

Portal, which is home to about 50 startups in Chicago that employ approximately 250 people, hosts quarterly meetings with venture capital firms that assess its startups. A year and a half ago, there wasn’t as much interest from investors, Flavin said.

“It’s very tenacious greenshoots,” said Michelle Hoffmann, executive director of the Chicago Biomedical Consortium. She moved to Chicago in 2019 after spending 17 years working in Boston’s biotech ecosystem. “Here what you’re seeing is an amazing effort to bootstrap.”

Industry leaders who spoke with

Endpoints News

pointed to a variety of factors driving Chicago’s biotech growth. The city recently

ranked 10th

on

R&D World

’s top 10 US biopharma hubs list based on patent filings, NIH funding and real estate metrics.

Chicago has 8.2 million square feet of occupied and vacant space for life sciences companies, according to a Cushman & Wakefield

report

in February. That’s well short of Boston’s 44.5 million square feet, but similar in size to Los Angeles (8.6 million), Seattle (9.8 million) and Raleigh-Durham (12.2 million).

“Over the last 24 months, we’ve seen a huge shift and now there’s actually available space,” said Max Zwolan, a VP at JLL who mainly focuses on life sciences.

At about 700,000 square feet, last year was Chicago’s best year in terms of leasing for R&D, manufacturing and other biotech space, according to Zwolan. In recent years, developers have constructed new labs that help retain local entrepreneurs and their startups who would have picked up their research and headed to the coasts a few years ago.

Coupled with the new lab space is an influx of attention on local biomedical research after the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative opened its Chicago biohub last year. Local leaders say the biohub has elevated the collaborative spirit with the region’s universities, which include Northwestern University, the University of Chicago and University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“At the biohub, we’re off to a really strong start, and I think that’s a testament to the talent pool that we have here in Chicago, as well as our ability to recruit from the coasts,” said Shana Kelley, president of CZ Biohub Chicago.

The biohub, which currently has a team of 30 people, plans to double in size next year.

“Everyone in the community here knows that we have all the necessary ingredients,” Kelley said.

The biohub shares a building with Flavin’s Portal Innovations. It’s one of multiple incubators and accelerators trying to foster new biotechs. There’s Fulton Labs in the West Loop, Illinois Science + Technology Park (ISTP) in suburban Skokie, and Chicago Technology Park (CTP) at the University of Illinois Chicago, among others. ISTP has housed companies like COUR Pharmaceuticals, which raised

$105 million in January

, while CTP is home to

CellTrans

, which received FDA approval last year for a diabetes islet cell therapy.

“When I started Vanqua, yes, we had the opportunity to go to either of the coasts,” Vanqua Bio CEO Jim Sullivan said. The company’s research came out of a local Northwestern University lab, and it’s now located at Fulton Labs. “That was absolutely a discussion with investors at the time, but there was a real desire to see: Can we build it in Chicago?”

Vanqua is one of multiple Chicago biotechs that have turned into clinical-stage companies in recent years. It

extended

its Series B by $45 million in July and

has produced

Phase 1 data for its experimental oral medicine for certain patients with Parkinson’s. COUR, meanwhile

,

has several drugs in development and inked a deal

with Roche’s Genentech

this month.

Alongside those successes is a belief that Chicago’s potential, in part, stems from a better quality of life than the coastal hubs. “The work-life balance and cost-efficiency of space is also fantastic,” said COUR CEO Dannielle Appelhans, a Chicago-area native.

“Most of the Midwest people who flock to those [coastal] cities don’t want to go,” said Joe Nolan, CEO of Jaguar Gene Therapy, a Deerfield-backed company that expects to enter the clinic early next year.

Insiders also say that because Chicago has fewer biotech startups, that means the turnover of scientists — perhaps the most crucial piece of a small biotech — is less of a fear for executives and investors. There is a small but influential set of big drugmakers based in the region, including AbbVie and Horizon, which has rebranded its massive building with Amgen insignia following its $28 billion takeover.

Ryan Clarke got a PhD from the University of Illinois Chicago and then moved to Boston to work at cell therapy company Sana Biotechnology. He found the employee turnover frustrating and moved home to Chicago during the pandemic to create his own cell therapy startup based on his PhD research. It’s called Syntax Bio, and it recently closed the first part of its Series A.

“It was like a revolving door at a lot of well-capitalized startups. That was a scary thing to see, because a lot of people would just get acclimated with a project and then they’d be looking around for what would be the next best thing down the street,” Clarke said. “In Chicago, that was definitely not going to be the case.”

Phase 1AcquisitionCell Therapy

09 Jul 2024

The company recently conducted a Type C meeting with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is cleared to proceed with dosing of pediatric patients (2+ years) with JAG201 with expansion into adults (18+ years) following the pediatric cohort

The first gene therapy clinical trial to evaluate therapeutic impact in a genetic form of autism and Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Site initiation to begin immediately and patient enrollment anticipated in Q12025.

There are currently no treatments for the ~46,000 individuals in the U.S. with autism due to SHANK3 haploinsufficiency and those diagnosed with Phelan-McDermid syndrome

JAG201 has been granted Rare Pediatric Disease designation and Fast Track designation by the FDA

LAKE FOREST, Ill.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Jaguar Gene Therapy, a clinical-stage biotechnology company accelerating breakthroughs in gene therapy for patients suffering from severe genetic diseases including those that impact sizeable patient populations, today announced the receipt of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) responses from a Type C meeting regarding the Phase I clinical trial for JAG201, a gene replacement therapy that targets a genetic form of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) where a SHANK3 mutation or deletion is present, and Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Specifically, the company received the FDA’s agreement to administer JAG201 to both pediatric and adult patients. Jaguar Gene Therapy plans to dose the first pediatric patient in Q1 of 2025 with expansion into adults following the pediatric cohort.

“We are pleased to have reached agreement with the FDA to dose both pediatric and adult patients in our initial Phase I clinical trial of JAG201. Our preclinical data suggest that the administration of the gene therapy early in life provides a clear potential for benefits to be realized,” said Joe Nolan, CEO of Jaguar Gene Therapy. “Our hope is that potential early success in the pediatric population will open the door to evaluating JAG201 in broader patient populations. We look forward to continuing to work with the FDA, key opinion leaders and advocacy organizations in our efforts to bring forward a gene therapy treatment for autism spectrum disorder due to SHANK3 haploinsufficiency and genetically confirmed Phelan-McDermid syndrome.”

“I think intervening earlier in a patient’s course of illness to address the underlying deficits caused by the SHANK3 deficiency while individuals are still actively undergoing development will provide a greater potential for benefit,” said Alexander Kolevzon, M.D., Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “There is an incredibly high unmet need among people living with Phelan-McDermid syndrome, and we expect there will be many eligible patients to participate in this important clinical trial.”

JAG201 delivers a functional SHANK3 minigene via an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) vector to target neurons in the central nervous system. The therapy is administered via a one-time unilateral intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection, targeting the entire brain and spinal cord. JAG201 is designed to transduce haploinsufficient neurons to provide proper SHANK3 levels and to durably restore the synaptic function required for learning and memory, which underlie appropriate neurodevelopment and maintenance of cognitive, communicative, social and motor skills. The program is exclusively licensed from Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Recently, the FDA granted Rare Pediatric Disease designation for JAG201. The designation is granted for products that treat serious and life-threatening rare pediatric diseases. Under this program, companies are eligible to receive a priority review voucher for a subsequent marketing application for a different product following approval of a product with Rare Pediatric Disease designation.

The FDA has also granted Fast Track designation for JAG201 based on the potential for the therapy to address a high unmet medical need for patients living with ASD where a SHANK3 mutation or deletion is present, and Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Currently, there are no therapeutic treatments approved for SHANK3 haploinsufficiency. Fast Track status allows for enhanced communication and collaboration between the FDA and drug developers, potentially accelerating the delivery of treatments to patients.

About SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in ASD and Phelan-McDermid syndrome

SHANK3 haploinsufficiency leads to synaptic dysfunction, disrupting communication between nerve cells. It causes a reduction of several key receptors and signaling proteins at excitatory synapses, resulting in impaired synaptic formation and function. Adequate synapse function is an essential prerequisite of all neuronal processing, including higher cognitive functions and learning.

SHANK3 haploinsufficiency causes Phelan-McDermid syndrome (also known as 22q13.3 deletion syndrome), a rare genetic disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000.1,2 Genetic sequencing studies indicate that SHANK3 mutations may be present in approximately 0.5%-0.69% of patients with ASD, equating to around 46,000 patients in the U.S., including approximately 10,000 pediatric patients under the age of 18, although diagnosed cases are perceived as low by clinical experts given the barriers of access and low adoption of genetic testing in the diagnostic journey of ASD.3,4,5,6 In the subset of ASD patients who also have moderate to profound intellectual disability (ID), the prevalence of SHANK3 mutations increases from less than 1% to 2.12%.3,7

About Jaguar Gene Therapy

Jaguar Gene Therapy, LLC is a clinical-stage biotechnology company dedicated to accelerating breakthroughs in gene therapy for patients suffering from severe genetic diseases including those that impact sizeable patient populations. The company is made up of a proven team of experts who have first-hand experience in bringing novel gene therapy treatments to patients and their families. Jaguar is rapidly advancing an initial pipeline of three programs. The company’s lead program targets severe neurodevelopmental disorders caused by SHANK3 haploinsufficiency, due to loss of function mutations or deletions in SHANK3 including a genetic form of autism spectrum disorder and Phelan-McDermid syndrome. A clinical trial in pediatric patients is planned to begin in Q1 of 2025. The second pipeline program targets Type 1 galactosemia and the third targets Type 1 diabetes. Jaguar’s key investors include Deerfield Management Company, ARCH Venture Partners and Eli Lilly and Company. For more information, please visit and follow Jaguar Gene Therapy on LinkedIn.

References

1. Costales JL et al. Neurotherapeutics 2015; 12 (3): 620–630.

2. What is Phelan-McDermid syndrome? Available at: . Accessed January 2023.

3. Betancur C et al. Mol Autism 2013; 4 (1): 17.

4. Jaguar Gene Therapy market research, 2022; data on file.

5.

6.

7. Leblond CS et al. PLoS Genet 2014; 10 (9): e1004580.

Disclosure

Dr. Alexander Kolevzon has served as a paid consultant for Jaguar Gene Therapy.

Fast TrackPhase 1Gene Therapy

28 Feb 2024

Panelists from left to right: MeiraGTx CEO Alexandra Forbes, Jaguar Gene Therapy CEO Joe Nolan, and Lexeo Therapeutics CEO Nolan Townsend. Credit: Justine Ra/GlobalData

With

gene therapy

programs, it is challenging to maintain the balancing act between the benefit and risk of a given indication, explained Nolan Townsend, CEO of Lexeo Therapeutics.

Townsend was speaking at the two-day 2024 BIO CEO & Investor Conference in New York conference. On 6 February,

scalability

and development were the stars of discussions, with experts outlining the various factors involved in developing gene therapies.

There has been a progression in development from small, orphan monogenic diseases into areas of higher risk and unmet need that can encompass disease states that are harder to treat, said Joe Nolan, CEO of the US-based biotech Jaguar Gene Therapy

The gene therapy field has experienced more clinical holds than both biologics and small molecules because there were many unanswered questions on the ideal chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC), dosage, immune suppression regimen, and routes of administration, said Townsend. But as the field has begun answering these questions, the risk profile of gene therapies will substantially decrease over time, he added.

Aside from the balance of benefit and risk, another important consideration when developing gene therapies is determining how optimised the technology is to address a particular indication and how minimal a dose a patient can receive, said Alexandra Forbes, CEO of

MeiraGTx

. She provided an example of how MeiraGTx Parkinson’s program takes into account the smallest possible dosage and in turn, is associated with a lower cost of goods.

See Also:

Biotech execs say IRA is causing unintended effects for cancer drug development

AbbVie licenses OSE’s chronic inflammation therapy for $48m upfront

Providing a product at a price that the market can afford is essential, Forbes said. In addition, there needs to be a heavy emphasis on the budget impact of a given disease to move toward developing a cost-saving gene therapy, added Townsend.

Manufacturing is critical for therapy development

“Manufacturing your gene therapy is essential to your entire clinical development,” explained Forbes. MeiraGTx built its own facility as a startup because the processes required for the company’s biologics license application (BLA) study were not broadly available across CMOs at the time of study. The benefit of having manufacturing capacity/capability is the facilitation of commercialisation and scalability, with the bonus of established regulatory interactions and positive impact on cost of goods, she added.

However, it is difficult to find people who understand the level of detail required when manufacturing commercially viable gene therapy product, Nolan said.

The future of the gene therapy field lies in commercial-scale processes that are used in products like biologics, especially as technology catches up to the commercial demands of gene therapy indications, said Townsend.

Gene Therapy

100 Deals associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLC

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Jaguar Gene Therapy LLC

Login to view more data

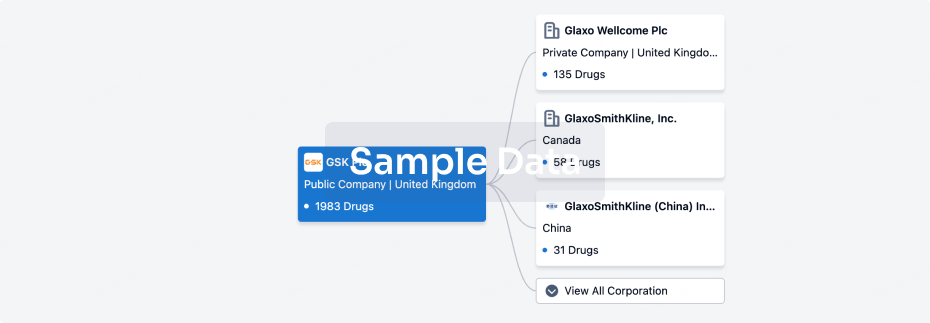

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 03 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

4

2

Preclinical

Phase 2 Clinical

1

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

JAG-201 ( SHANK3 ) | Phelan-McDermid syndrome More | Phase 2 Clinical |

JAG-301 ( PAX4 ) | Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1 More | Preclinical |

JAG-101 ( GALT ) | Galactosemias More | Preclinical |

WO2024178401 ( SHANK3 ) | Other Diseases More | Discovery |

WO2023102442 ( PAX4 ) | Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases More | Discovery |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

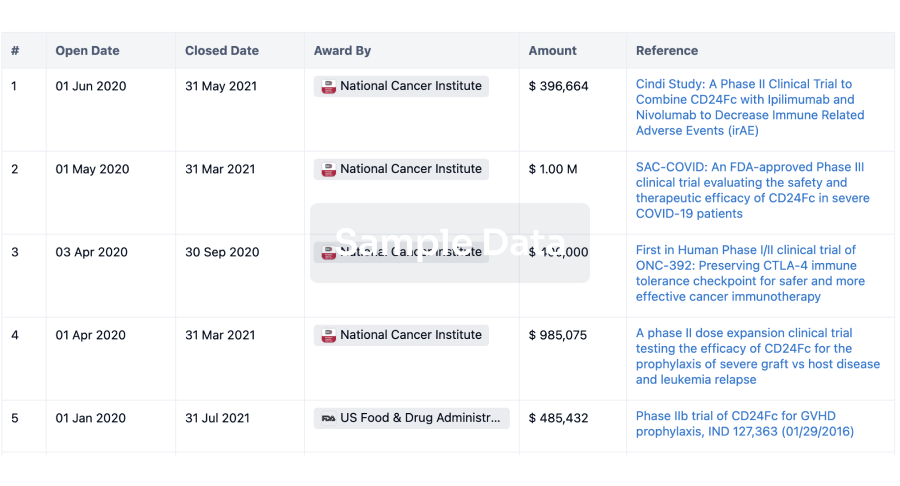

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free