Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Insitro, Inc.

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Tags

Nervous System Diseases

Digestive System Disorders

Neoplasms

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Neoplasms | 1 |

| Nervous System Diseases | 1 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| WRN(WRN RecQ like helicase) | 1 |

Related

2

Drugs associated with Insitro, Inc.Target |

Mechanism WRN inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

100 Clinical Results associated with Insitro, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Insitro, Inc.

Login to view more data

12

Literatures (Medical) associated with Insitro, Inc.01 Jun 2025·STAR Protocols

Protocol for in vitro phase separation of N terminus of CIDEC proteins

Article

Author: Lyu, Xuchao ; Lu, Yiming ; Zhu, Zanzan ; Chen, Feng-Jung ; Wang, Jianqin ; Li, Peng

03 Apr 2025·The Journal of Physical Chemistry B

Application of Amber Suppression To Study the Role of Tyr M210 in Electron Transfer in Rhodobacter sphaeroides Photosynthetic Reaction Centers

Article

Author: Boxer, Steven G. ; Tran, Khoi N. ; Faries, Kaitlyn M. ; Mathews, Irimpan I. ; Kirmaier, Christine ; Weaver, Jared B. ; Magdaong, Nikki Cecil Macasinag ; Holten, Dewey ; Kirsh, Jacob M.

01 Jun 2024·Contemporary Clinical Trials

Getting our ducks in a row: The need for data utility comparisons of healthcare systems data for clinical trials

Article

Author: Cannings-John, Rebecca ; Mintz, Harriet ; Wright-Hughes, Alexandra ; Apostolidou, Sophia ; Farrin, Amanda J ; Murray, Macey L ; Pinches, Heather ; Carpenter, James ; Robling, Michael ; Love, Sharon B ; Clayton, Tim ; Harper, Charlie ; Menon, Usha ; Mafham, Marion ; Cosgriff, Rebecca ; Lugg-Widger, Fiona ; Ahmed, Saiam ; Gentry-Maharaj, Aleksandra ; Clout, Madeleine ; Gilbert, Duncan C ; Langley, Ruth E ; Mackenzie, Isla S ; Yorke-Edwards, Victoria ; James, Nicholas D ; Sydes, Matthew R ; Lessels, Sarah ; Bliss, Judith M ; Bloomfield, Claire

34

News (Medical) associated with Insitro, Inc.19 Mar 2025

Insight’s ophthalmic imaging bioresource includes 35 million images of the eye. Credit: PeopleImages.com – Yuri A/Shutterstock.

Moorfields Eye Hospital’s Insight Health Data Research Hub and insitro have announced a partnership to develop an AI foundation model for the genetic discovery of ocular biomarkers and therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative and associated conditions.

Insight’s ophthalmic imaging bioresource includes 35 million images of the eye.

Among these are optical coherence tomography (OCT) images, connected to decades of clinical info encompassing chronic metabolic, neurodegenerative and ophthalmic disorders related to ageing.

The AI model will support Insitro’s neuroscience programmes, focusing on detecting OCT-based signatures related to the risk and progression of dementia.

Moorfields Eye Hospital, as part of National Health Service (NHS), gathers a significant volume of OCT images prior to a diagnosis of dementia. It expedites insitro’s offerings in discovering biological targets backed by human genetics.

This collection is crucial to develop a model to distinguish between the OCTs of individuals who develop this condition and those who do not.

The scale of the OCT images, combined with dementia diagnosis data, will facilitate the creation of a quality model for insitro’s drug discovery initiatives.

insitro founder and CEO Daphne Koller stated: “OCT data at this scale contains a treasure trove of information about human health, providing a new window into diseases of the brain, the eye and more.

“Building a world-class foundation model with Insight at Moorfields will help us unravel disease biology and identify novel targets, including for our programmes in neurodegenerative diseases.”

The combined effort is set to leverage the Insight-developed eye research data infrastructure at Moorfields, which has been instrumental in the field of Oculomics.

Foundation models are adaptable across multiple tasks ,eliminating the requirement for task-specific training from the ground up.

insitro teamed up with Eli Lilly in October 2024

to develop treatments for metabolic diseases.

21 Dec 2024

Welcome back to Endpoints Weekly, your review of the week’s top biopharma headlines. Want this in your inbox every Saturday morning? Current Endpoints readers

can visit their reader profile

to add Endpoints Weekly. New to Endpoints? Sign up

here

.

A reminder that our newsletters are going dark starting next Tuesday, December 24, which includes the Weekly next weekend. We’ll be back to regular programming in the new year starting January 2nd. Hope you all have a wonderful holiday season! —

Max Gelman

We revealed our (newly) annual tradition of naming

this year’s winners and losers in biopharma

. Check out how we rated megadeals vs. megarounds, regulatory flexibility vs. authority, CRISPR stocks vs. RNA editing, and many more. Plus, it’s the only story each year we’re allowed to use emojis, so please indulge us with our frivolity. 😀

Novo Nordisk

reported

the highly anticipated Phase 3 data for CagriSema on Friday, saying patients managed 22.7% weight loss after 68 weeks. That figure came in below the benchmark the company and many analysts had set as a bar for success, sending Novo’s stock down nearly 20%. Novo had hoped CagriSema could represent a next-generation GLP-1 drug with once-weekly injections as opposed to daily, but those goals become significantly more challenging with Friday’s data.

Late to the GLP-1 game, Merck

made its move

this week by licensing an oral GLP-1 candidate from the Chinese company Hansoh Pharma. Merck will pay $112 million upfront and up to $1.9 billion in biobucks, adding to a busy year of dealmaking for the company in China. Merck has been open about its ability to do multibillion-dollar deals, and CEO Rob Davis has emphasized the importance of combination approaches, particularly in obesity. The move also disappointed the vocal crowd of Viking Therapeutics enthusiasts, who were hoping for a Merck takeout.

A review of public statements by Andrew Ferguson and Mark Meador — President-elect Donald Trump’s picks for the Federal Trade Commission — shows a strong focus on big tech and far less about drugmakers. While pharma mergers were the subject of increased scrutiny under current FDA Commissioner Lina Khan, Ferguson and Meador have hinted at a more traditional review of consolidation. What happens with pharmacy benefit managers, which have been the subject of

bipartisan interest

, remains to be seen. Check out Jared Whitlock’s analysis

here.

Non-opioid painkillers is an area where Vertex, long known for cystic fibrosis, has been attempting to push into for several years. But a readout this week demonstrated that, while a Phase 2 study met its primary endpoint, the company’s drug performed similarly to placebo in the trial — raising

major questions

about the drug’s efficacy in the study and its future in chronic pain. The pill targets peripheral neurons and blocks a sodium channel important for pain signaling called NaV1.8.

SPOTLIGHT

Chicago’s biotech scene is growing up. What’s fueling it?

Exclusive: Insitro makes headway on the harder road, discovering new ALS drug target

David Epstein gets $140M for Ottimo’s bifunctional take on hot PD-1xVEGF field

MORE IN R&D

PEOPLE

DEALS

MORE IN FDA

MORE IN PHARMA

MORE IN MANUFACTURING

MORE IN HEALTH TECH

Clinical ResultPhase 3Phase 2

18 Dec 2024

SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif.--(

BUSINESS WIRE

)--insitro, a machine learning-enabled drug discovery and development company, today announced it has received $25 million from Bristol Myers Squibb (NYSE: BMY) representing both the achievement of discovery milestones and the selection of the first novel target for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that was identified and validated by insitro. The companies signed a collaboration agreement in 2020 to discover new therapies for this disease that lacks any disease modifying treatment.

ALS is a devastating disease that occurs sporadically. It causes the progressive degeneration of nerve cells in the spinal cord and brain, leading to muscle spasms, impaired speech and gait, and eventual respiratory failure. Life expectancy from diagnosis is three to five years, and all cases are fatal.

To disentangle the complexity of ALS biology, insitro built and scaled a platform, using machine learning (ML), for drug discovery with three distinct proprietary elements, including:

A collection of more than 200 engineered and patient ALS cell lines representing a comprehensive collection of ALS genetics and sporadic patients, complemented by a unique protocol for rapid, ML-enabled differentiation of motor neurons that model the disease;

High-content imaging capabilities, fit-for-purpose for machine learning (ML), to identify disease mechanisms; and

A proprietary, ML-enabled technology for pooled optical screening in human cells (POSH) to uncover genetic modifiers of disease-relevant cellular phenotypes.

Powered by this platform, researchers identified several novel gene targets that rescue functional deficits found in ALS patients. Knockdown of these targets reverted protein and RNA profiles that are found in ALS patient spinal cords, including proven markers of ALS pathology. These effects were also observed in cell lines capturing the genetics of ALS patients. The first credentialed target from the collaboration is now moving into drug discovery, while other targets continue to be studied.

“ALS is a grievous disease that causes immense suffering. Identifying potentially transformative targets with high conviction for such a complex disease is a testament to insitro’s state-of-the-art disease models and our cutting-edge cell-ML platform,” said Daphne Koller, Ph.D., founder and CEO of insitro. “Our team’s hard work and determination has been matched by the quality of our partnership with Bristol Myers Squibb scientists and leaders, who understood and invested in our vision early on. Thanks to both of those factors, our scientists were able to uncover meaningful insights and surface potentially viable targets that we hope will lead to meaningful treatments for patients in need.”

“Bristol Myers Squibb is committed to unlocking new frontiers in neuroscience, based on validated targets linked to causal human biology,” said Richard Hargreaves, Senior Vice President and Head of Bristol Myers Squibb’s Neuroscience Thematic Research Center. “We look forward to working with insitro to advance drug discovery for this novel target, as we strive to tackle some of the most pressing areas of unmet patient needs.”

With the selection of the first candidate target, the parties will continue to work closely to advance therapeutics targeted to this high value target and pathway. Bristol Myers Squibb will progress the program through clinical development and maintains the option for the selection of additional targets.

Under the terms of the collaboration agreement, insitro received a $50 million upfront payment and is eligible to receive up to more than $2 billion in further development, regulatory and commercial milestones in addition to royalty payments on net product sales.

About insitro

insitro is a machine learning-enabled drug discovery and development company creating a new approach for target and drug discovery. We integrate multimodal data from human cohorts and cellular models with the power of AI and machine learning. insitro is uncovering genetic targets and new therapeutic hypotheses, leveraging human and cell data to increase the probability of success. These insights provide the starting point for discovering new molecules, which we either build with our in-house, AI-enabled drug discovery platforms or with partners that extend our impact. With more than $700 million in capital raised to date, insitro is building a "pipeline through platform" with a focus on metabolic disease, neurodegeneration and oncology. Approaching the clinic, insitro aims to deploy its AI models to run smaller, better powered trials, enrolling the patients who can benefit most. Learn more at insitro.com

License out/in

100 Deals associated with Insitro, Inc.

Login to view more data

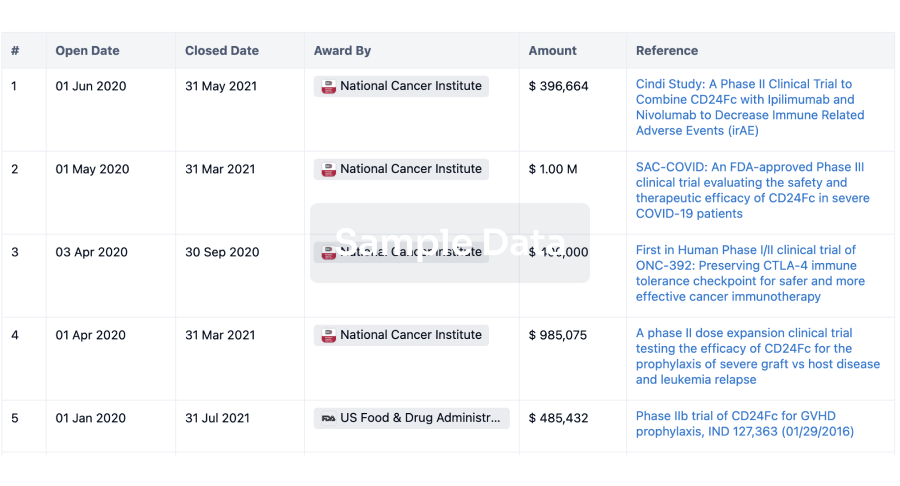

100 Translational Medicine associated with Insitro, Inc.

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 04 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Preclinical

2

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

MOMA-341 ( WRN ) | Neoplasms More | Preclinical |

Neurodegenerative diseases(Insitro) | Neurodegenerative Diseases More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free