Request Demo

Last update 19 Oct 2025

Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Last update 19 Oct 2025

Overview

Tags

Skin and Musculoskeletal Diseases

Immune System Diseases

Otorhinolaryngologic Diseases

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Immune System Diseases | 1 |

| Infectious Diseases | 1 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 2 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| IKKε x TBK1 | 1 |

| H1 receptor(Histamine H1 receptor) | 1 |

Related

2

Drugs associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.Target |

Mechanism IKKε inhibitors [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date17 Dec 1996 |

Target |

Mechanism H1 receptor antagonists |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. Japan |

First Approval Date17 Jan 1970 |

10

Clinical Trials associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.CTR20241159

恩格列净二甲双胍缓释片(25mg/1000mg)在中国健康受试者中空腹和餐后给药条件下随机、开放、单剂量、两制剂、两序列、两周期、双交叉生物等效性试验

[Translation] A randomized, open-label, single-dose, two-formulation, two-sequence, two-period, double-crossover bioequivalence study of empagliflozin metformin extended-release tablets (25 mg/1000 mg) in Chinese healthy subjects under fasting and fed conditions

按有关生物等效性试验的规定,选择Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc持证,Patheon Pharmaceuticals Inc.生产的恩格列净二甲双胍缓释片(商品名:Synjardy® XR,规格:25mg/1000mg)为参比制剂,对山东力诺制药有限公司提供的受试制剂恩格列净二甲双胍缓释片(规格:25mg/1000mg)进行空腹和餐后给药人体生物等效性试验,比较受试制剂中药物的吸收速度和吸收程度与参比制剂的差异是否在可接受的范围内,评价两种制剂在空腹和餐后给药条件下的生物等效性。同时观察健康受试者口服受试制剂和参比制剂后的安全性。

[Translation]

According to the relevant provisions of bioequivalence tests, Empagliflozin Metformin Sustained-Release Tablets (trade name: Synjardy® XR, specification: 25mg/1000mg) licensed by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and produced by Patheon Pharmaceuticals Inc. were selected as the reference preparation. The human bioequivalence test of the test preparation Empagliflozin Metformin Sustained-Release Tablets (specification: 25mg/1000mg) provided by Shandong Linuo Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. was conducted on fasting and postprandial administration to compare whether the absorption rate and degree of the drug in the test preparation were within the acceptable range with the reference preparation, and to evaluate the bioequivalence of the two preparations under fasting and postprandial administration conditions. At the same time, the safety of the test preparation and the reference preparation after oral administration was observed in healthy subjects.

Start Date29 Apr 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

CTR20240176

盐酸鲁拉西酮片在中国成年健康受试者中的一项单中心、随机、开放、空腹和餐后单次给药、两制剂、两序列、四周期、完全重复交叉生物等效性研究

[Translation] A single-center, randomized, open-label, fasting and postprandial single-dose, two-formulation, two-sequence, four-period, fully repeated crossover bioequivalence study of lurasidone hydrochloride tablets in healthy adult Chinese subjects

主要研究目的:

考察单次口服(空腹/餐后)受试制剂盐酸鲁拉西酮片【规格:40 mg(按C28H36N4O2S?HCl计)】与参比制剂【商品名:罗舒达®,规格:40 mg(按C28H36N4O2S?HCl计)】在中国健康人体的相对生物利用度,分析两种制剂的药代动力学参数,评价两制剂的生物等效性,为该药的申报及临床用药提供参考依据。

次要研究目的:

评价单次口服(空腹/餐后)受试制剂和参比制剂在中国成年健康受试者中的安全性。

[Translation]

Main research objectives:

To investigate the relative bioavailability of the test preparation lurasidone hydrochloride tablets [Specification: 40 mg (calculated as C28H36N4O2S?HCl)] and the reference preparation [trade name: Luo Shuda®, specification: 40 mg (calculated as C28H36N4O2S?HCl)] in healthy Chinese subjects after a single oral administration (fasting/after meals), analyze the pharmacokinetic parameters of the two preparations, evaluate the bioequivalence of the two preparations, and provide a reference for the application and clinical use of the drug.

Secondary research objectives:

To evaluate the safety of the test preparation and the reference preparation in healthy Chinese adult subjects after a single oral administration (fasting/after meals).

Start Date20 Feb 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

CTR20233011

中国健康受试者空腹及餐后状态下单次口服吡拉西坦片的单中心、开放、随机、两制剂、两序列、两周期、双交叉人体生物等效性试验

[Translation] A single-center, open-label, randomized, two-formulation, two-sequence, two-period, double-crossover bioequivalence study of a single oral dose of piracetam tablets in Chinese healthy volunteers under fasting and fed conditions

研究健康受试者空腹及餐后单次口服受试制剂吡拉西坦片(山东力诺制药有限公司,规格:0.8g)与参比制剂吡拉西坦片(商品名:Nootropil®,规格:0.8g)在吸收程度和速度方面是否存在差异,评价受试制剂和参比制剂在空腹及餐后条件下给药时的生物等效性,观察受试制剂和参比制剂在健康受试者中的安全性。

[Translation]

To investigate whether there are differences in the extent and rate of absorption of the test preparation piracetam tablets (Shandong Linuo Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., specification: 0.8g) and the reference preparation piracetam tablets (trade name: Nootropil®, specification: 0.8g) taken orally on an empty stomach or after a meal in healthy subjects, to evaluate the bioequivalence of the test preparation and the reference preparation when administered on an empty stomach or after a meal, and to observe the safety of the test preparation and the reference preparation in healthy subjects.

Start Date27 Sep 2023 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Login to view more data

2

Literatures (Medical) associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.01 Dec 2023·Current medicinal chemistry

YF343, A Novel Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, Combined with CQ

to Inhibit- Autophagy, Contributes to Increased Apoptosis in Triple-

Negative Breast Cancer

Article

Author: Lu, Wen-xia ; Qiu, Huiran ; Yang, Fei-fei ; Duan, Wen-qi ; Zhang, Hua ; Liu, Na ; Ge, Di ; Zhang, Jing ; Wu, Yong-mei ; Lin, Yan ; Luo, Tingting ; Han, Li-na

Background::

Compounds that target tumor epigenetic events are likely to constitute

a prominent strategy for anticancer treatment. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis)

have been developed as prospective candidates in anticancer drug development,

and currently, many of them are under clinical investigation. We assessed the anticancer

efficacy of a now hydroxamate-based HDACi, YF-343, in triple-negative breast cancer

development and studied its potential mechanisms.

Methods::

YF-343 was estimated as a novel HDACi by the HDACi drug screening kit.

The biological effects of YF-343 in a panel of breast cancer cell lines were analyzed by

Western blot and flow cytometry. YF-343 exhibited notable cytotoxicity, promoted apoptosis,

and induced cell cycle arrest. Furthermore, it also induced autophagy, which plays

a pro-survival role in breast cancer cells.

Results::

The combination of YF-343 with an autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) significantly

suppressed breast tumor progression as compared to the YF-343 treatment alone

both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, the molecular mechanism of YF-343 on autophagy

was elucidated by gene chip expression profiles, qPCR analysis, luciferase reporter

gene assay, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, immunohistochemical analysis,

and other methods. E2F7, a transcription factor, promoted the expression of ATG2A

via binding to the ATG2A promoter region and then induced autophagy in triple-negative

breast cancer cells treated with YF-343.

Conclusion::

Our studies have illustrated the mechanisms for potential action of YF-343

on tumor growth in breast cancer models with pro-survival autophagy. The combination

therapy of YF-343 and CQ maybe a promising strategy for breast cancer therapy.

01 Sep 2022·Analytica chimica acta

An extracellular matrix biosensing mimetic for evaluating cathepsin as a host target for COVID-19

Article

Author: Liu, Hongkai ; Wang, Ying ; Hu, Jianguo ; Lin, Xia ; Li, Jinlong ; Li, Hao ; Liu, Chen ; Hou, Wenmin ; Zhou, Lei

To combat the new virus currently ravaging the whole world, every possible anti-virus strategy should be explored. As the main strategy of targeting the virus itself is being frustrated by the rapid mutation of the virus, people are seeking an alternative "host targeting" strategy: neutralizing proteins in the human body that cooperate with the virus. The cathepsin family is such a group of promising host targets, the main biological function of which is to digest the extracellular matrix (ECM) to clear a path for virus spreading. To evaluate the potential of cathepsin as a host target, we have constructed a biosensing interface mimicking the ECM, which can detect cathepsin from 3.3 pM to 33 nM with the limit of detection of 1 pM. Based on our quantitative analysis enabled by this biosensing interface, it is clear that patients with background diseases such as chronic inflammation and tumor, tend to have higher cathepsin activity, confirming the potential of cathepsin to serve as a host target for combating COVID-19 virus.

1

News (Medical) associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.22 Dec 2023

Financial consideration is the most important factor why foreign pharmas outsource commercialization in China.

Big Pharma companies have often talked about the major opportunities that await in China. But as price cuts play out and internal priorities shift, multinational companies are reworking their business models in the country.

In the last few months of 2023, Pfizer, GSK, Sanofi and Biogen have each tapped local partners to help commercialize their products in China. With marketing responsibilities shifting to other firms, job cuts were expected at each of those large drugmakers.

It’s not a new approach for foreign drugmakers to tap local partners in China, Justin Wang, head of L.E.K. Consulting’s China practice, pointed out in an email interview with Fierce Pharma. But these deals are on the rise lately, Wang explained, partly because “there is increasing pricing and competitive pressure in the market, especially for mature products, leaving reduced [return on investment] for in-house commercial resources.”

Pfizer in November unveiled a deal with Keyuan Pharma, granting the Shanghai Pharma subsidiary exclusive rights to distribute and promote its pneumococcal vaccine Prevenar 13 (known as Prevnar 13 in the U.S.) in China.

“We believe that this partnership will leverage the synergies of both companies and make Prevenar 13 available to a much broader population in China,” a Pfizer spokesperson told Fierce Pharma.

Pfizer’s announcement came about a month after GSK signed on Chongqing Zhifei Biological Products to distribute its shingles vaccine, Shingrix, in China. Zhifei made a name as the marketer of Merck’s HPV shot Gardasil in China. Thanks to Gardasil’s impressive growth in the country, Merck earlier this year surpassed AstraZeneca as China’s largest foreign pharma company by sales. Before AZ, that title belonged to Pfizer.

Local companies have strong track records from prior Big Pharma partnerships, Wang noted, so that’s another reason why the deals are gaining in popularity in recent months. With the two new collaborations, three of the world’s top-selling vaccines are now all handled by local firms in China.

The vaccine commercialization model is different in China than in the U.S. As local Chinese CDC agencies serve as direct customers of the immunizations, vaccines have no commercial synergies with other drugs, Wang explained.

Chinese regulators divide vaccines into two types: mandatory and voluntary. Gardasil, Prevnar and Shingrix all belong to the Class 2 voluntary group. The Class 2 vaccines require heavy investment and intensive market education, which can be burdensome for foreign pharma companies. Zhifei, for example, has assembled a commercial team of more than 3,000 people, he noted.

Pfizer’s existing Prevenar China team—reportedly 400 people strong—is being disbanded, according to local reports. Pfizer’s spokesperson declined to comment on the number of jobs affected by the Keyuan deal.

The move comes as Pfizer cuts costs around the globe to save $4 billion annually by the end of 2024 in response to declining COVID product sales. The company’s spokesperson said the Keyuan partnership is “independent of any other company initiative or business decision.”

It’s not just vaccines

At GSK, it appears the company is further restructuring its China business beyond the Shingrix pact. According to local reports from a few days ago, the British drugmaker is outsourcing commercialization of two older meds, the COPD inhaler Anoro and the anti-epileptic Lamictal.

Sales staffers supporting those drugs are also expected to be let go, according to the reports. GSK declined to comment on this subject.

Beyond Pfizer and GSK, Biogen has established a strategic partnership with a local company for its multiple sclerosis portfolio in China, a company spokesperson confirmed with Fierce Pharma. Biogen sells MS drugs Fampyra and Tecfidera in the country.

Similar to Pfizer, Biogen is also undergoing a companywide cost-cutting initiative, which aims to reduce its workforce by 1,000 and save $1 billion in operating expenses by 2025.

Almost simultaneous to the Biogen accord, Sanofi China unveiled a “broad and deep” collaboration with Shanghai Pharma. The two companies will partner on treatments for cardiovascular diseases, central nervous system disorders and cancer so that Sanofi can build a business model that “better fits the local market and optimizes operations,” the French pharma said in a Dec. 14 release published on its official WeChat account.

Sanofi wouldn’t comment on the exact products involved. Local reports said the company is delegating marketing responsibilities around MS drug Aubagio, the thrombosis med Clexane (also known as Lovenox), anti-serum phosphorus therapy Renvela, as well as chemotherapies oxaliplatin and docetaxel.

“To support the execution of our strategy, we are looking at adjusting our organization setup and optimizing our commercial presence, identifying partners capable of ensuring the sustainable distribution of our portfolio of medicines for patients,” a Sanofi spokesperson told Fierce Pharma.

As part of its third-quarter earnings, Sanofi launched an initiative to save up to 2 billion euros from 2024 to the end of 2025. The company’s recent corporate update led to a rare, 20% price drop in Sanofi’s stock.

In striking the deals, both Sanofi and Biogen have opted not to pursue selling MS meds on their own in the country. That’s despite Biogen winning national coverage for Tecfidera.

MS is a rare disease in China with a very low diagnosis rate, making it a tough market, L.E.K.’s Wang noted.

“Rare disease drugs are not easy for any pharma to manage in China,” Wang said. “You need to establish the diagnosis and treatment protocols and referral networks to find the right patients.”

Commercial trade-offs

Meanwhile, China’s National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) poses a sticking point for some products because it does not allow the high prices for rare disease medicines that are seen in the U.S. Therefore, market access remains a challenge for medicines with high prices, Wang added.

The NRDL represents a trade-off between sharp discounts and a large patient base, and calculations around revenue, profitability and commercial investment determine whether a drug is better off staying outside of the program, Wang said.

Even after winning national coverage, drugs aren’t guaranteed commercial success under NRDL. While national insurance opens up broader market access, “you still need efforts to be listed in each hospital’s formulary, educate physicians, and ensure reimbursement implementation in local jurisdictions,” Wang noted.

Therefore, a company typically needs to ramp up marketing investment to be able to reap the benefits of NRDL.

Lately, many Western pharma companies have decided not to pursue NRDL coverage for some of their drugs. None of the major PD-1/L1 inhibitors are currently on the NRDL, and foreign pharmas’ antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), including AZ and Daiichi Sankyo’s Enhertu and Gilead Sciences’ Trodelvy, also didn’t make the cut.

Besides the NRDL, China’s volume-based procurement (VBP) program is designed to cut prices for older off-patent meds. Foreign pharmas have formed several local partnerships for mature products that need deeper “coverage” than market education, Wang noted. These deals also depend on the pharma company’s interest to explore “lower-tier” markets outside the major cities, he said.

Various forms of engagement

Financial trade-offs appear to be the most important factor accelerating the trend of Big Pharma companies reducing their marketing responsibilities in China, Wang said. But geopolitical risk is “certainly something influencing decision-making—especially at the HQs.”

The volatile political environment means some smaller drugmakers may be hesitant to go big on China, but large pharmas are still committed to investing in China in various forms, Wang noted.

For example, as part of GSK’s reshuffling in China, the company set a goal to become a top 10 foreign pharma in China by 2030. The U.K. drugmaker recently also in-licensed two ADCs from Chinese biotech Hansoh Pharmaceutical.

“You can find molecules in China and [often] the Chinese companies just want the [domestic] rights so you can negotiate … [to] take it globally,” GSK’s chief commercial officer, Luke Miels, recently told The Financial Times

“A key theme we see is that [Big Pharma companies] are actively optimizing their commercial models,” L.E.K.’s Wang observes, “on the one hand exploring various forms of partnerships to access external resources, and on the other hand increasing in-house team efficiencies through new digital/omnichannel customer engagement models.”

VaccineLicense out/in

100 Deals associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Shandong Keyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Login to view more data

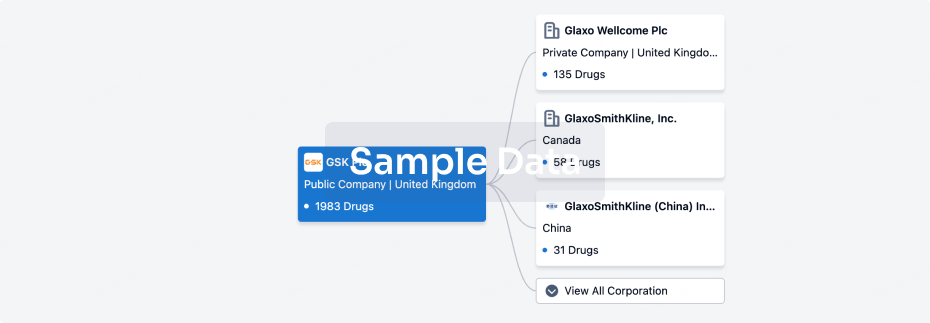

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 18 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Approved

2

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Clemastine Fumarate ( H1 receptor ) | Rhinitis, Allergic More | Approved |

Amlexanox ( IKKε x TBK1 ) | Ulcer More | Approved |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

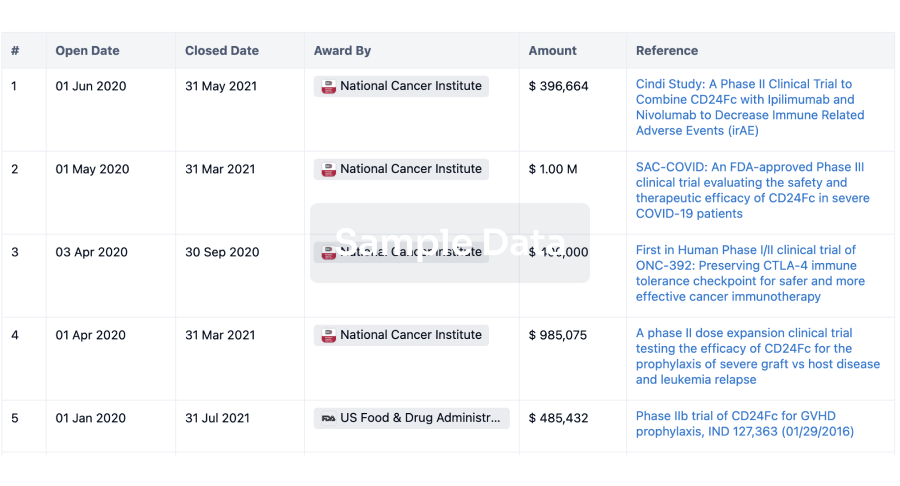

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free