Request Demo

Last update 14 Feb 2026

Zion Pharma Ltd.

Last update 14 Feb 2026

Overview

Tags

Neoplasms

Respiratory Diseases

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Neoplasms | 2 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 2 |

Related

2

Drugs associated with Zion Pharma Ltd.Target |

Mechanism ATM inhibitors |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 1 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism SMARCA2 inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

100 Clinical Results associated with Zion Pharma Ltd.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Zion Pharma Ltd.

Login to view more data

13

News (Medical) associated with Zion Pharma Ltd.23 Oct 2025

Roche on Thursday reported stagnant sales in its pharmaceutical unit for the third quarter, hit by currency effects and a decline for two of its top selling drugs, Hemlibra and Vabysmo. The division generated revenue of CHF 11.6 billion ($14.5 billion) in the three-month period, up 7% when stripping out currency effects, as the company's overall sales slipped 1% to CHF 14.9 billion, missing analyst expectations of CHF 15.2 billion.Sales of Hemlibra declined 3% to CHF 1.1 billion, down 9% in the US as a result of buying patterns for the haemophilia A therapy, while revenue from Vabysmo fell by the same percentage to CHF 996 million, hit by a contraction in the US branded market, where sales of the eye-disease treatment dropped 11%. When stripping out currency effects, the two drugs posted growth of 4% in the quarter.Along with the declines for Hemlibra and Vabysmo, Roche's best seller Ocrevus saw a 1% drop in quarterly sales to CHF 1.7 billion, although growth was 6% on a constant exchange rate basis. Other declines were seen for Perjeta (-21% to CHF 703 million) — as patients switch to the newer breast cancer drug Phesgo — as well as for Avastin (-17% to CHF 241 million) and Herceptin (-20% to CHF 257 million) due to continued biosimilar erosion.While biosimilar competition is here to stay for a number of Roche's medicines, including an increased impact on Actemra, the drugmaker indicated that the overall hit this year is expected to be CHF 800 million, down from an earlier forecast of CHF 1 billion.Speaking Thursday on an analyst call, Teresa Graham, chief executive of Roche's pharmaceuticals unit, said that regarding the impact of patent expiries in 2025, "the pace picks up in Q4, and that is largely due to Actemra." She added "we are starting to see that kick in the US… and we would expect that to accelerate as we go through the end of the year."Roche said that bright spots in the quarter include Xolair, with sales climbing 25% to CHF 781 million, and Phesgo, which saw revenue jump 42% to CHF 630 million.Raised profit guidanceDespite the below par quarterly sales performance, Roche maintained its full-year outlook for revenue growth in the mid-single digits and even hiked its earnings forecast. The company expects core earnings per share to grow this year in the high single-digit to low double-digit range, up from an earlier estimate of high single-digit growth.CEO Thomas Schinecker said that Roche's growth momentum, its efforts to mitigate any short-term impact of US tariffs, and cost control measures drove the increase in guidance. "Our earnings were growing in the low double-digit range. And that made us comfortable that we can increase our guidance," Schinecker noted.Commenting on the outlook, Vontobel analyst Stefan Schneider expressed surprise at the raised profit guidance, given that third-quarter sales came in below expectations, with most of Roche's big hitters missing estimates.Meanwhile, Schinecker also indicated that talks with the US government have taken place and are ongoing with respect to an agreement around drug pricing. However, he declined to comment on how such a deal would stack up against similar ones reached between the Trump administration and AstraZeneca and Pfizer. "We are in constant exchange with the US government, that is as much as I can say at the moment."Focus on pipelineWith continued biosimilar pressure on Roche's revenue, the drugmaker is hoping that acquisitions — including a recent deal to buy 89bio for $2.4 billion — and its internal pipeline will help offset declines. "Our momentum is…reflected in our pipeline with a number of positive clinical read-outs and a record 10 potentially transformative medicines progressing into the final phase of development," remarked Schinecker. In the third quarter, Roche moved the dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist CT-388 into late-stage development, with Phase III progression also for CT-868 in type 1 diabetes; the RNAi therapeutic zilebesiran for uncontrolled hypertension; cevostamab in multiple myeloma; and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor RG6596 for HER2+ breast cancer, which is partnered with Zion Pharma.Meanwhile, pivotal Phase III readouts are still expected this year for Gazyva (obinutuzumab) in systemic lupus erythematosus, fenebrutinib in primary-progressive multiple sclerosis and PiaSky (crovalimab) for atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome. "By the end of the decade, we expect Phase III…results for up to 19 new medicines," Schinecker noted.($1 = CHF 0.797584)

AcquisitionPhase 3BiosimilarFinancial Statement

16 Jan 2025

Roche has a big problem. With competition threatening some of its older and most lucrative biologic drugs, the Swiss pharmaceutical giant expects that, in three years time, sales from these assets will decline by roughly $8 billion.Despite this looming danger, Roches leaders have, at least publicly, put on a brave face. Theyve reshaped the companys structure and research priorities, and assured shareholders that new products and a handful of experimental medicines should more than make up for the financial losses. Some of those assets were developed internally, but others came from a recent tear of dealmaking.Since the summer of 2023, Roche has inked three acquisitions worth more than $1 billion including the $7.2 billion purchase of Televant and entered into a laundry list of licensing agreements and research pacts. Those smaller deals include a partnership with AI chipmaker Nvidia, several bets on genetic medicines, as well as investments into hot areas of science like protein degraders and a class of cancer therapies known as ADCs.Critical investors could argue Roches dealmaking is a bit scattered. The companys main interests span five research fields, from oncology, immunology and neuroscience to cardiometabolic and ophthalmology. But perhaps expectedly, Boris Zatra, the longtime head of business development for Roche Group, doesnt see it that way.We make sure we try to look at everything that's available, Zatra said. The art is to make sure your funnel is efficient. You don't want to miss something, but you also cannot boil the ocean.Zatra, who Roche appointed as head of corporate business development last year, spoke to BioPharma Dive about the tenets of the companys dealmaking strategy. He also explained why Roche hasnt done supersized acquisitions lately, and how it plans to tap into the rapidly advancing Chinese biotechnology market.The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.BIOPHARMA DIVE: You were Roches head of business group development for 12 years, a period which brought the rise of immuno-oncology, the ups and downs of cell and gene therapy, and, more recently, a bit of a resurgence in neuroscience and a huge push into obesity drugs. How has Roches BD strategy changed over that time?BORIS ZATRA: I'm not sure the strategy would have changed. The biggest change I witnessed is the reorganization we did last year, where we decided to bring my team and the partnering team into one team corporate business development which basically provides under one umbrella end-to-end BD capabilities.Why did we do that? There are internal factors and external factors. On the internal side, youve heard of our One Pharma strategy, the bar on R&D excellence. We went through quite a long process to make sure we really define what we are after. Our ambitions are clear. They are high.On the external side, what I would say is the innovation across therapeutic areas, across modalities, across geographies is very exciting, but that's a huge space to search. It's really important to be structured, to be systematic, to be rigorous, to make sure that everybody knows how they fit, what we want to do, what's our risk appetite.All things being equal, executing a deal today is probably more challenging than it was four or five years ago. It's more complicated, it's more competitive, it's more expensive, it's more intimidating, its more sophisticated.Outside of Televant, Roche hasnt made a $5+ billion acquisition in quite some time. In fact, the company seems much more interested in smaller research partnerships. Do you see the average size of your deals changing anytime soon?ZATRA: If you look at our size as a company and our financial means, yes, it's been a while since we have been in a deal environment where we would max out. I think that's been a constraint.In terms of looking ahead: if you take 2023 and 2024, I think that's a relatively good representation of what we aspire to continue doing. 2023 with Carmotand Televant, you have more late-stage, building up capabilities in an accelerated way. In 2024, it was a bit more spread. Regor was Phase 1 oncology, CDK4/6 with ADCs.There is recognition that we also have to take a portfolio approach. We have to invest in early-stage, mid-stage and late-stage.By design, you would want to place many more bets at an early stage, because it also takes more of those to make it all the way through. We clearly aspire and hope that we will be doing deals across the spectrum.A sign with the Roche logo stands in front of a tall building.Permission granted by RocheAn analyst once told me that larger, acquiring companies have an internal ceiling for things like premiums. Your Poseida deal had a premium over 200%. Do premiums and things like that influence your teams BD decisions?ZATRA: The answer is yes and no. When we do deals, we have to be comfortable with the valuation we pay. Youre referring specifically about public deals. In the case of public deals, you have a price reference, and then there is a premium being paid. If the deal happened, it means the seller and the buyer reached an agreement on price.We're sophisticated players. We look at trading multiples. We look at transaction multiples of similar deals. It's not always easy, but at least weve got benchmarks. We do the bottom-up valuation, really looking at the prospects, the platforms, the compounds, assuming they make it all the way to market with the probability adjusted. We do a deal where we can justify the value.There is a benchmark for premium. Typically, you will pay the average, which is in the 60% to 80% branch. Where the data gets a bit more complicated with respect to premium is when you get into smaller [deals]. First, the comparisons are a bit more complicated. And when you get to the sub-$1 billion market cap, then youve got liquidity [considerations].The smaller deals tend to attract sometimes some of the highest premiums. That's because perhaps the valuation attributed by the market was not fully reflective of the intrinsic value of the asset.One trend thats accelerated is the number of deals involving assets from China. Roche itself recently inked deals with the Chinese biotechs Regor, Innovent and Zion Pharma. Whats driving this, do you expect it to continue and how will it impact biotech in the U.S.?ZATRA: China is establishing itself as the second largest place of innovation outside of the U.S. We saw an inflection point last year, which was really outlined by the deals which happened. And it was not only the deals which happened in 2024, but also, if you take the example of bispecifics, the PD1/VEGF [drugs]. You had the Akeso-Summit relationship and the readouts, which put a huge focus on what's happening in China.I don't know if this will change, but my sense is: to create innovation, you need to create an ecosystem. You need the entrepreneurs, you need the capital, you need the science, you need the universities. You need all that ecosystem to work in a very synergistic way. You don't create that out of nowhere. So when it happens, to that level of maturity, my sense is this is pretty real and pretty solid. I don't think this will necessarily change.The trend I'm seeing more is people wanting to ensure they are equipped to screen and to tap into that market. Because it is a bit more complicated. That market is not highly intermediated. The opportunities they are not in databases. You really have to go on the ground. And if you take a given target, you have potentially 10, 20 companies working on that target. So then, the art becomes to know all of those companies, and then to filter through which of those are really interesting.To exploit the potential of that market, from a BD perspective, you need to be equipped for that. It's less interrogated, less sophisticated, less mature, probably, as a BD market than the U.S. is.One of the main areas people think of when they think of Roche is oncology. What do you see as the role for these emerging PD-1/VEGF drugs? Are you convinced theyll be the next big thing in immunotherapy?ZATRA: It's very difficult to comment. What is for sure is some data that has been published has been very impressive. The questions we need to answer are: Do we understand exactly what is happening? What exact mechanism? Because those components are not new. VEGF is not new. PD-1 is not new. So what makes it so special when you bind them the way they've been bound as bispecifics?There are now tens of companies getting into this space. Unless I'm wrong, I don't think there's been a lot of disclosure of overall survival data. Clearly, as we know in that space, overall survival will always be very important.I think it's very exciting, and let's see how things unfold. I think maybe later this year, at latest, there will be more data that will shed a better light as to how big of an opportunity these will be for patients. '

AcquisitionPhase 1

28 Nov 2024

The series A investment round secures resources for advancing global Phase I/II clinical programs and orchestrating the company's global footprint expansion.

SHANGHAI, Nov. 28, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- Allink Biotherapeutics, a clinical-stage biotechnology company pioneering next-generation bispecific antibody and antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) therapeutics, today announced the successful completion of a $42 million Series A financing. The financing round was led by Lanchi Ventures, a preeminent global early-stage technology investor known for backing breakthrough innovations, with participation from an elite syndicate of new investors including Yuanbio Venture Capital, Legend Capital and C&D Emerging Industry Equity Investment, alongside strong support from existing shareholders Gaorong Ventures and Med-Fine Capital.

"Since our company's inception a little over a year ago, AllinkBio has rapidly advanced from lead asset PCC to clinical development stage," said Hui Feng, Ph.D., Founder and Chief Executive Officer of AllinkBio. "We are grateful for the continued support from existing shareholders and delighted to welcome new investors who recognize both our scientific excellence and capability of translating scientific findings into clinical applications. Their support enables us to accelerate the development of our diverse pipeline spanning multiple modalities including next-generation ADCs and bispecific antibodies targeting oncology and immunology diseases. Looking ahead, we are poised to achieve multiple pipeline milestones in the coming months as we pursue our long-term mission of bringing innovative therapeutics to patients with significant unmet medical needs."

"AllinkBio's exceptional execution speed and quality in advancing its lead program from preclinical to clinical stage, led by Dr. Feng, one of the leading figures in China's biopharmaceutical industry, demonstrates the company's high competitiveness in the field," said Lanchi Ventures. "AllinkBio's innovative approach to ADC development presents a compelling opportunity in the targeted oncology therapeutics space."

"Our continued investment in AllinkBio reflects our strong conviction in the company's scientific excellence and execution capabilities," said Jiangtao Yu, Ph.D., Managing Director at Gaorong Ventures. "Since our initial investment, we have been impressed by the company's rapid advancement in both platform development and pipeline progression. We are excited to strengthen our commitment through this Series A financing."

"We are delighted to have witnessed the fast and steady development of AllinkBio. Dr. Feng and his team's dedicated work in progressing two highly promising ADC drug candidates into clinical stage within one and half years since company inception has been really impressive. We believe the company has great potential and will continuously support its endeavor in developing innovative drugs for patients in need globally." said Angel Round lead investor Vince Deng, Ph.D., Partner of Med-Fine Capital.

The Series A financing proceeds will be deployed to advance:

Global clinical development of lead candidates ALK201 and ALK202 through Phase 1 studies in Australia, the United States and China

Enrichment of current portfolio by developing multiple highly competitive new assets in oncology and immunology

Further development of the company's proprietary bispecific antibody and ADC technology platform

Global footprint expansion to achieve world prominence

The successful completion of this round of financing marks a pivotal moment in AllinkBio's growth trajectory. With the new financial resources in place, combined with the company's efficient R&D capabilities, AllinkBio is well-positioned for expedited growth toward new heights on both its product and corporate development fronts.

About AllinkBio

Founded in 2023, AllinkBio is a clinical stage biotechnology company leveraging its innovative proprietary platforms in bispecific antibodies and ADCs to develop a diverse pipeline of First-in-Class (FIC) and Best-in-Class (BIC) therapeutics. AllinkBio aims to develop treatment paradigm shifting new drugs for patients in the oncology and immunology disease areas and address critical unmet medical needs globally.

About Lanchi Ventures

Lanchi Ventures (LCV), a leading early-stage venture capital firm with offices in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Beijing, focuses on investing in entrepreneurs who leverage technological innovations to create a sustainable impact. With its heritage in Silicon Valley since 1998, Lanchi Ventures (LCV) manages over $2 billion in capital through multiple funds and has invested in over 200 portfolio companies, including Gaussian Robotics, TCab, UniUni, Agibot, Galbot, Moonshot, Li Auto (NASDAQ: LI), QingCloud (688316.SH), WaterDrop (NYSE: WDH), Ganji/58.com, Guazi, etc. The firm has been recognized by Forbes, Fortune, Preqin, and others. For further information, please visit .

About Gaorong Ventures

Founded in 2014, Gaorong Ventures is focused on early and growth-stage investments, with a specialty in new technology, healthcare, internet and new consumption. We have 24 IPO portfolios, amongst which, many of them have advanced to be leaders in their perspective industries, including Pinduoduo (NASDAQ: PDD), Huya (NYSE: HUYA), BOSS Zhipin (NASDAQ: BZ), Roborock (688169.SH), etc. We continue to invest in the healthcare industry and are committed to discovering and accompanying leading companies in the fields of drug discovery, medical instrumentation and testing, digital health and medical services. Representative examples include Alto Neuroscience(NYSE: ANRO), ProfoundBio (acquired by Genmab), Sironax, Cornerstone Robotics, HYGEA, United Family Healthcare, Saint Bella, etc.

About Yuanbio Venture Capital

Yuanbio Venture Capital is a leading healthcare investment firm focusing on early and growth stage companies. Based in Suzhou bioBay, YuanBio keeps a global vision. With both RMB and USD funds, YuanBio has built up a portfolio of over 190 companies, covering biotech, medical devices, IVD, and healthcare services fields. The firm has seen great investment returns with 19 of its portfolio companies listed on the STAR, Hong Kong Stock Exchange and Nasdaq. YuanBio has received multiple awards as one of the leading healthcare VCs in China. With passion, dedication and expertise, YuanBio strives to become one of the most successful healthcare venture capital firms in China.

About Med-Fine Capital

Med-Fine Capital is a leading healthcare-focused venture capital firm in China, known for its capability of identifying promising entrepreneurs and investing in their NewCo formation round. Med-Fine manages multiple RMB and USD funds, investing across the healthcare sector including biotech, medical devices, diagnostics, healthcare technology and services. To date, it has grown a portfolio of approximately 70 companies, including Hanyu Medical, Mabworks, ImmVira Pharma, Zion Pharma, LYNK Pharmaceuticals, Eccogene, Pharma Legacy, MagAssist, Alebund, Allorion Therapeutics, Allink Biotherapeutics, Castalysis Bioscience, and VelaVigo. Med-Fine is dedicated to becoming a reputable investment institution with global impact.

About Legend Capital

Founded in 2001, Legend Capital is a leading VC&PE investor focusing on the early-stage and growth-stage opportunities in China, with offices across Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Seoul and Singapore. It currently manages USD and RMB funds of over US$10 billion and has invested in around 600 companies, covering technology, healthcare, consumer, enterprise service and intelligent manufacturing sectors. Over the years, Legend Capital has become a widely recognized name in bridging key resources in China and overseas through cross-border activities, and a valuable partner to Chinese and overseas investors. Legend Capital values long-term sustainable investment and incorporates ESG into its long-term development strategy. As a UNPRI signatory since November 2019, Legend Capital is among the first group of top VC/PE firms in China to join the initiative.

About C&D Emerging Industry Equity Investment

C&D Emerging Industry Equity Investment is a professional equity asset management institution under C&D Group (Fortune Global 500). Established in 2014, our mission is to "create new value and help more emerging enterprises achieve better development." We specialize in new economic fields such as healthcare, advanced manufacturing, TMT/consumption.

SOURCE Allink Biotherapeutics

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

Phase 1ADC

100 Deals associated with Zion Pharma Ltd.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Zion Pharma Ltd.

Login to view more data

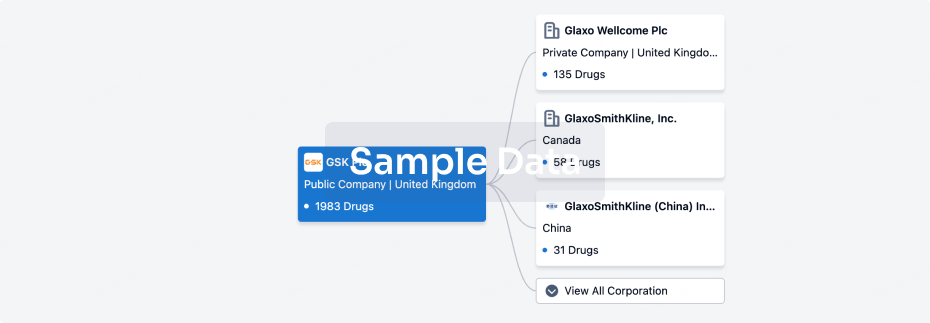

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 13 Mar 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Preclinical

2

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

ZN-B-2262 ( ATM ) | Solid tumor More | Preclinical |

ZN-7035 ( SMARCA2 ) | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

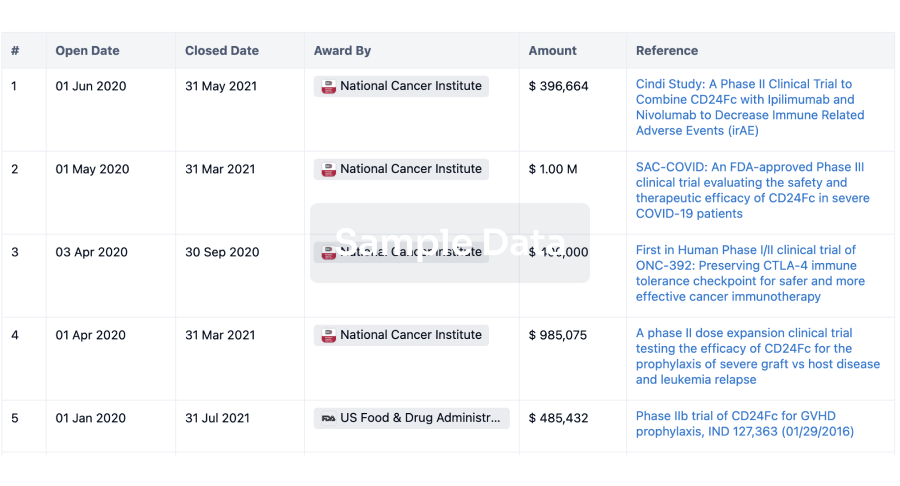

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free