Request Demo

Last update 14 Feb 2026

Terran Biosciences

Last update 14 Feb 2026

Overview

Tags

Nervous System Diseases

Other Diseases

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Nervous System Diseases | 2 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 2 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| NIMA related kinase family | 1 |

Related

2

Drugs associated with Terran BiosciencesTarget- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

CN117956991

Patent MiningMechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseDiscovery |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

1

Clinical Trials associated with Terran BiosciencesNCT05727189

A Phase 1 Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetic Study of R-Idazoxan HCl Extended-Release (TR-01-XRR), S-Idazoxan HCl Extended-Release (TR-01-XRS) and Racemic Idazoxan HCl Extended-Release (TR-01-XR) in Healthy Participants

Four-part study of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of 3 forms of TR-01-XRR, 1 form of TR-01-XRS, and 1 form of TR-01-XR in healthy adults.

Start Date14 Feb 2023 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Terran Biosciences

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Terran Biosciences

Login to view more data

16

News (Medical) associated with Terran Biosciences21 Oct 2024

Seaport will use the $225m funding to advance its pipeline of experimental drugs for neuropsychiatric disorders. Credit: eamesBot via Shutterstock.

PureTech-founded Seaport Therapeutics has raised $225m in a Series B financing round to support the development of new prodrug treatments for psychiatric disorders.

Seaport plans to use the new funds to push forward its pipeline of experimental drugs, including its most advanced candidate, SPT-300, which is being advanced into a Phase IIb trial for major depressive disorder.

SPT-300 is an oral prodrug of brexanolone, a neurosteroid compound with known anti-depressant effects. Topline results from Seaport’s SPT-300 Phase IIa

proof-of-concept

trial were reported in November 2023, where the study met its primary endpoint of salivary cortisol response.

The financing was led by General Atlantic, with backing from several other major investors such as T Rowe Price, Foresite Capital, and

Goldman Sachs

. The latest funding comes after the company’s launch in April 2024, when it secured $100m in initial funding from founding investors ARCH Venture Partners, Sofinnova Investments, Third Rock Ventures, and co-founder

Puretech Health

.

The funding will also support Seaport’s Glyph technology platform, which helps drugs be absorbed more efficiently by using the body’s lymphatic system. This platform could improve the delivery of drugs that have a low bioavailability, or have side effects such as liver enzyme elevations or hepatoxicity, says the company.

See Also:

FDA approves Astellas’ VYLOY for gastric cancer treatment

Intercept’s liver disease drug Ocaliva faces FDA approval delay

The company has several other candidates in its pipeline, including SPT-320, an experimental prodrug of agomelatine being advanced into Phase I studies to treat generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). By leveraging Glyph, SPT-320 bypasses liver first-pass metabolism, allowing for lower dosing and reduced liver exposure. Seaport is also developing SPT-348 for mood and neuropsychiatric disorders and has several preclinical programmes under its belt.

Prodrugs are medications that start as inactive or less active, and once inside the body, are converted into the active form, usually through natural processes involving enzymes. Prodrugs can be used to enhance drug delivery, minimise side effects, and improve drug solubility and oral bioavailability.

In the announcement accompanying the financing, Seaport’s founder Steve Paul said: “The development of important new neuropsychiatric medicines is often halted due to poor drug-like properties or unacceptable tolerability, challenges that our Glyph platform can now uniquely address.”

The potential of prodrugs was recently in the spotlight in the case of xanomeline, which initially faced tolerability challenges, but once resolved,

was approved

Cobenfy (formerly KarXT) for schizophrenia. Xanomeline helps reduce symptoms of schizophrenia, but it can cause unpleasant side effects that include nausea and sweating. Trospium was added to the drug to block these side effects while still allowing xanomeline to work in the brain. Now, Cobenfy is expected to earn $2.99bn in revenues by 2030, as per GlobalData analysis.

GlobalData is the parent company of

Pharmaceutical Technology.

New York-based Terran Biosciences is taking it a step further by developing

two prodrug versions

of Cobenfy. Terran aims to curb issues surrounding medication adherence by optimising its dosing schedule to a more convenient once-daily oral regimen (TerXT), and a multi-month injectable (TerXT LAI).

Phase 2Drug ApprovalPhase 1Clinical Result

27 Sep 2024

Cobenfy introduces a new mechanism of action to the schizophrenia treatment landscape and an additional option for patients. Credit: 13_Phunkod via Shutterstock.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved

Bristol Myers Squibb

’s first-in-class schizophrenia drug Cobenfy (xanomeline-trospium), providing patients with a new treatment option not seen in decades.

The novel drug – named Cobenfy – introduces a new mechanism of action to the schizophrenia treatment landscape by targeting cholinergic receptors as opposed to dopamine receptors. The market for schizophrenia drugs has long been dominated by dopamine-blocking antipsychotics, which are associated with significant side effects such as Parkinsonian symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain.

Originally developed by

Karuna Therapeutics

and named KarXT, BMS inherited the drug as part of a $14bn acquisition, which was finalised in March 2024. The acquisition is set to pay off as Cobenfy is set to pull in $2.99bn in sales in 2030, according to GlobalData forecasts.

GlobalData is the parent company of

Pharmaceutical Technology

.

Cobenfy is a twice-daily pill that combines two drugs: one that targets muscarinic receptors M1 and M4, which increase activity in the parasympathetic nervous system, and another that lessens side effects from activating those receptors. Clinical trial data has shown that the drug relieves symptoms such as delusions without some of the drastic side effects caused by currently approved antipsychotics.

See Also:

Boehringer Ingelheim opens $66.8m new cancer research facility

AskBio and Belief BioMed partner to advance gene therapies

The excitement surrounding Cobenfy also stems from its ability to address both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Unlike dopamine receptors, M1 and M4 receptors work on positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions, and negative symptoms that include reduced emotional output, speech, and motivation.

Data from the

Phase III EMERGENT-3 trial

(NCT04738123) showed that the drug demonstrated an 8.4-point reduction in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score compared to placebo at week five. However, the new drug comes with side effects like any other therapy. The prescribing information includes warnings that Cobenfy can cause urinary retention, increased heart rate, decreased gastric movement, or angioedema (swelling beneath the skin) of the face and lips.

In the announcement accompanying the approval, Tiffany Farchione, director of the Division of Psychiatry, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said: “This drug takes the first new approach to schizophrenia treatment in decades. This approval offers a new alternative to the antipsychotic medications people with schizophrenia have previously been prescribed.”

Some experts have expressed concerns about the

twice-daily dosing schedule

of the drug, noting that treatment effectiveness often depends on consistent medication adherence – something that can be difficult for schizophrenia patients, especially given the side effects of traditional antipsychotics. However, in a Q1 2023 earnings call, Karuna’s former CEO Bill Meury suggested that adherence to Cobenfy could surpass standard schizophrenia treatments.

To tackle this issue, Terran Biosciences are developing a prodrug version of xanomeline-trospium, called TerXT. Terran’s candidates keep Cobenfy’s formulation while optimising its dosing schedule to a more convenient once-daily oral regimen, and a multi-month injectable.

BMS said patients can enrol in a patient assistance scheme called the Cobenfy Cares programme in late October when the drug is set to be available.

Phase 3AcquisitionDrug ApprovalClinical Result

19 Aug 2024

Bristol Myers Squibbs highly anticipated schizophrenia drug KarXT is fast approaching a September deadline for the Food and Drug Administration to decide on approval. Yet competition already looms for a market thats estimated to soon be worth billions of dollars.KarXT, a so-called muscarinic agonist, may become the first new kind of schizophrenia drug in decades. Close behind it is AbbVies emraclidine, which works in a similar fashion.People with schizophrenia experience a broad range of symptoms, from hallucinations and delusions to cognitive impairments and social withdrawal. Clinical testing has shown that, like KarXT, emraclidine, which AbbVie acquired from Cerevel Therapeutics in a multibillion-dollar deal, is effective at controlling symptoms without the debilitating side effects or drawbacks of traditional antipsychotics, which cause almost three-quarters of patients to abandon treatment.But experts say once-daily dosing versus twice-daily treatment, and a potentially more gut-friendly formulation, may give emraclidine an edge over KarXT, which Bristol Myers Squibb acquired in a $14 billion acquisition of Karuna Therapeutics.Emraclidine is designed to reduce the excess dopamine signaling that causes schizophrenic symptoms, but without blocking the receptors altogether. By blocking specific M4 receptors, rather than others more broadly, the drug could help patients deal with symptoms without the side effects that come with less precise treatment.A Phase 1b study found people who received emraclidine for six weeks saw statistically significant improvements on a standardized scale of symptom severity without side effects like weight gain, restlessness and movement disorders.By selectively targeting the M4 receptor, emraclidine resulted in infrequent gastrointestinal side effects, with rates similar to placebo, Dawn Carlson, AbbVies vice president of neuroscience development, wrote in an email.AbbVie is testing the drug in two mid-stage trials that support approval, and expects to release topline data later this year.According to Carlson, the Cerevel acquisition, finalized this month, not only gave AbbVie emraclidine but several preclinical and clinical-stage drugs that fit into the pharma giants existing portfolio.There are multiple programs in Cerevels pipeline across several psychiatric and neurological conditions such as schizophrenia, Parkinsons disease and mood disorders, where there continues to be significant unmet need for patients, she wrote.Emraclidine may also have applications outside of schizophrenia for dementia-related psychosis in diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinsons.Several other new schizophrenia drugs are advancing through testing. While many have the same dopamine or serotonin targets as traditional antipsychotics, others rely on novel approaches like KarXT and emraclidine.Neurocrine Biosciences is testing a muscarinic agonist in a Phase 2 study with Nxera Pharma. The company also has another mid-stage schizophrenia candidate called luvadaxistat. Boehringer Ingelheim is in Phase 3 with its drug iclepertin, a selective glycine transporter 1 inhibitor.Meanwhile, Terran Biosciences is looking to compete with a prodrug therapy thats meant to improve on KarXTs twice-daily dosing schedule with a once-daily pill. Its also developing a long-acting injection, dubbed TerXT LAI.Its unclear how either KarXT or emraclidine might compare to these investigational drugs. AbbVie has yet to conduct any head-to-head studies comparing emraclidine to other potential therapies.An increasingly competitive market may create hurdles for drug companies, but it could create new options for people with schizophrenia. The condition affects less than 1% of the population, but is among the top 15 leading causes of disability worldwide.There remains a significant unmet need for more therapies with different mechanisms of action in the treatment of schizophrenia, Carlson wrote. '

Phase 2Phase 1AcquisitionPhase 3Clinical Result

100 Deals associated with Terran Biosciences

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Terran Biosciences

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 06 Mar 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

1

1

Preclinical

Other

3

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

TerXT | Schizophrenia More | Preclinical |

CN117956991 ( NIMA related kinase family )Patent Mining | Nervous System Diseases More | Discovery |

Therapeutic program (CoNCERT Pharmaceuticals) | Central Nervous System Diseases More | Discontinued |

TR-36 | Depressive Disorder More | Pending |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

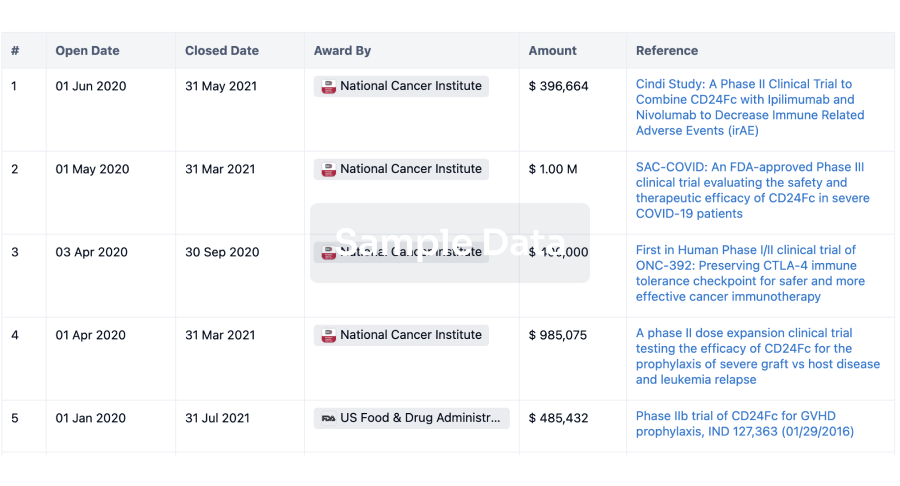

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free