Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Veterans Administration Medical Center

Private Company|California, United States

Private Company|California, United States

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Tags

Nervous System Diseases

Respiratory Diseases

Digestive System Disorders

Small molecule drug

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Neoplasms | 1 |

| Nervous System Diseases | 1 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 1 |

Related

3

Drugs associated with Veterans Administration Medical CenterTarget- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism β-lactamase inhibitors |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePending |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism Bacterial DNA gyrase inhibitors |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePending |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

100 Clinical Results associated with Veterans Administration Medical Center

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Veterans Administration Medical Center

Login to view more data

4,485

Literatures (Medical) associated with Veterans Administration Medical Center16 Apr 2025·Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network

The Financial Toxicity Tumor Board: 5-Year Update on Practice and a Guide to Implementation

Article

Author: Blackley, Kris ; Wheeler, Mellisa ; Moroe, Jaynie ; Mesa, Ruben ; Hensel, Caitlin ; Knight, Thomas G. ; Feild, Donna ; Turan, Wendy Jo ; Chai, Seungjean ; Raghavan, Derek ; Warden, Hughes R.

01 Apr 2025·Molecular Psychiatry

Cortico-limbic volume abnormalities in late life depression are distinct from β amyloid and white matter pathologies

Article

Author: Insel, Philip S. ; Saykin, Andrew J ; Insel, Philip S ; Rhodes, Emma ; Bickford, David ; Weiner, Michael W. ; Tosun, Duygu ; Morin, Ruth ; Koeppe, Robert ; Raman, Rema ; Kassel, Michelle ; Burns, Emily ; Kryza-Lacombe, Maria ; Toga, Arthur ; Butters, Meryl A ; Butters, Meryl A. ; Mackin, R. Scott ; Landau, Susan ; Jack, Clifford ; Mackin, R Scott ; Aisen, Paul ; Weiner, Michael W ; Saykin, Andrew J. ; Nelson, Craig

03 Mar 2025·Journal of Clinical Investigation

Patterns of autoantibody expression in multiple sclerosis identified through development of an autoantigen discovery technology

Article

Author: Tedder, Thomas ; Harlow, Danielle E ; Heuler, Joshua ; Lanker, Stefan ; Zhu, Minghua ; Kountikov, Evgueni ; Zhang, Weiguo ; Hayward, Brooke ; DiCillo, Europe B ; Piette, Elizabeth R ; Pisetsky, David ; Korich, Julie ; Bennett, Jeffrey L

60

News (Medical) associated with Veterans Administration Medical Center09 Mar 2025

PARIS, France and TARRYTOWN, NY, USA I March 8, 2025 I

Positive results from the pivotal ADEPT phase 2/3 study evaluating the investigational use of Dupixent (dupilumab) in adults with moderate-to-severe bullous pemphigoid (BP) were shared in a late-breaking oral presentation at the 2025 American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting. BP is a chronic, debilitating, and relapsing skin disease with underlying type 2 inflammation and characterized by intense itch and blisters, reddening of the skin, and painful lesions.

Victoria Werth, MD

Chief of the Division of Dermatology at the Philadelphia Veterans Administration Hospital, Professor of Dermatology and Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and the Veteran’s Administration Medical Center, and principal investigator of the study

“People with bullous pemphigoid live with unrelenting itch, blisters, and painful lesions that can be debilitating and make it difficult to function daily. Moreover, current treatment options can be challenging for this primarily elderly patient population because they work by suppressing their immune system. By targeting the underlying type 2 inflammation, which is a key driver for bullous pemphigoid, Dupixent is the first investigational biologic to show sustained disease remission and reduce disease severity and itch compared to placebo in a clinical study.”

The ADEPT study

met all

primary and key secondary endpoints, enrolling 106 adults with moderate-to-severe BP who were randomized to receive Dupixent 300 mg (n=53) every two weeks after an initial loading dose or placebo (n=53) added to standard-of-care oral corticosteroids (OCS). During treatment, all patients underwent a protocol-defined OCS tapering regimen if control of disease activity was maintained. Sustained disease remission was defined as complete clinical remission with completion of OCS taper by week 16 without relapse and no rescue therapy use during the 36-week treatment period.

As presented at AAD, results for Dupixent-treated patients at 36 weeks, compared to those treated with placebo, were as follows:

In this elderly population, overall rates of adverse events (AEs) were 96% (n=51) for Dupixent and 96% (n=51) for placebo. AEs more commonly observed with Dupixent compared to placebo in at least 3 patients included peripheral edema (n=8 vs. n=5), arthralgia (n=5 vs. n=3), back pain (n=4 vs. n=2), blurred vision (n=4 vs. n=0), hypertension (n=4 vs. n=3), asthma (n=4 vs. n=1), conjunctivitis (n=4 vs. n=0), constipation (n=4 vs. n=1), upper respiratory tract infection (n=3 vs. n=1), limb injury (n=3 vs. n=2), and insomnia (n=3 vs. n=2). There were no AEs leading to death in the Dupixent group and 2 AEs leading to death in the placebo group.

In February, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

accepted

for priority review the supplemental biologics license application for Dupixent to treat BP. The FDA decision is expected by June 20,2025. Dupixent was previously granted orphan drug designation by the FDA for BP, which applies to investigational medicines intended for the treatment of rare diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. Additional applications are also under review around the world, including in the EU.

The safety and efficacy of Dupixent in BP are currently under clinical investigation and have not been evaluated by any regulatory authority.

About BP

BP is a chronic, debilitating, and relapsing skin disease with underlying type 2 inflammation that typically occurs in an elderly population. It is characterized by intense itch and blisters, reddening of the skin, and painful lesions. The blisters and rash can form over much of the body and cause the skin to bleed and crust, resulting in patients being more prone to infection and affecting their daily functioning. Approximately 27,000 adults in the US live with BP that is uncontrolled by systemic corticosteroids.

About the Dupixent BP pivotal study

ADEPT is a randomized, phase 2/3, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of Dupixent in 106 adults with moderate-to-severe BP for a 52-week treatment period. After randomization, patients received Dupixent or placebo every two weeks, with OCS treatment. During treatment, OCS taper was initiated after patients experienced two weeks of sustained control of disease activity. OCS tapering could start between four to six weeks after randomization and was continued as long as disease control was maintained, with the intent of completion by 16 weeks. After OCS tapering, patients were only treated with Dupixent or placebo for at least 20 weeks, unless rescue treatment was required.

The primary endpoint evaluated the proportion of patients achieving sustained disease remission at 36 weeks. Sustained disease remission was defined as complete clinical remission with completion of OCS taper by 16 weeks without relapse and no rescue therapy use during the 36-week treatment period. Relapse was defined as appearance of ≥3 new lesions a month or ≥1 large lesion or urticarial plaque (>10 cm in diameter) that did not heal within a week. Rescue therapy could include treatment with high-potency topical corticosteroids, OCS (including increase of OCS dose during the taper or re-initiation of OCS after completion of the OCS taper), systemic non-steroidal immunosuppressive medications, or immunomodulating biologics.

Select secondary endpoints evaluated at 36 weeks included:

About Dupixent

Dupixent (dupilumab) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the signaling of the interleukin-4 (IL4) and interleukin-13 (IL13) pathways and is not an immunosuppressant. The Dupixent development program has shown significant clinical benefit and a decrease in type 2 inflammation in phase 3 studies, establishing that IL4 and IL13 are two of the key and central drivers of the type 2 inflammation that plays a major role in multiple related and often co-morbid diseases.

Dupixent has received regulatory approvals in more than 60 countries in one or more indications including certain patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, eosinophilic esophagitis, prurigo nodularis, chronic spontaneous urticaria, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in different age populations. More than one million patients are being treated with Dupixent globally.

Dupilumab development program

Dupilumab is being jointly developed by Sanofi and Regeneron under a global collaboration agreement. To date, dupilumab has been studied across more than 60 clinical studies involving more than 10,000 patients with various chronic diseases driven in part by type 2 inflammation.

In addition to the currently approved indications, Sanofi and Regeneron are studying dupilumab in a broad range of diseases driven by type 2 inflammation or other allergic processes in phase 3 studies, including chronic pruritus of unknown origin, bullous pemphigoid, and lichen simplex chronicus. These potential uses of dupilumab are currently under clinical investigation, and the safety and efficacy in these conditions have not been fully evaluated by any regulatory authority.

About Regeneron

Regeneron (NASDAQ: REGN) is a leading biotechnology company that invents, develops and commercializes life-transforming medicines for people with serious diseases. Founded and led by physician-scientists, our unique ability to repeatedly and consistently translate science into medicine has led to numerous approved treatments and product candidates in development, most of which were homegrown in our laboratories. Our medicines and pipeline are designed to help patients with eye diseases, allergic and inflammatory diseases, cancer, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, neurological diseases, hematologic conditions, infectious diseases, and rare diseases.

Regeneron pushes the boundaries of scientific discovery and accelerates drug development using our proprietary technologies, such as

VelociSuite

®

,

which produces optimized fully human antibodies and new classes of bispecific antibodies. We are shaping the next frontier of medicine with data-powered insights from the Regeneron Genetics Center

®

and pioneering genetic medicine platforms, enabling us to identify innovative targets and complementary approaches to potentially treat or cure diseases.

For more information, please visit

www.Regeneron.com

or follow Regeneron on

LinkedIn

,

Instagram

,

Facebook

or

X

.

About Sanofi

We are an innovative global healthcare company, driven by one purpose: we chase the miracles of science to improve people’s lives. Our team, across the world, is dedicated to transforming the practice of medicine by working to turn the impossible into the possible. We provide potentially life-changing treatment options and life-saving vaccine protection to millions of people globally, while putting sustainability and social responsibility at the center of our ambitions.

SOURCE:

Sanofi

Clinical ResultPhase 3

04 Mar 2025

Research demonstrates the ability of copper-impregnated surfaces to kill both forms of the HAI-causing organism

TEMPLE, Texas, March 4, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- A federally-funded study published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology demonstrates the efficacy of copper-impregnated surface, EOSCU, in significantly reducing Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile or C. diff) spores. C. diff spores can persist on healthcare surfaces for months and cause HAIs among hospitalized patients. This research, conducted at Central Texas Veterans Health Care System in Temple, TX, investigated EOSCU, an American-made product manufactured by EOS Surfaces in Norfolk, Virginia.

Continue Reading

EOScu is an EPA-registered, copper-infused solid surface that kills >99.9% of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in under 2 hours, keeping surfaces safe between cleanings and protecting patients from healthcare-associated infections.

"At EOS Surfaces, we have always placed science at the heart of everything we do, and partnering with the Veterans Administration on this project has been a true honor," says Ken Trinder, CEO of EOS Surfaces and inventor of EOSCU. "This collaboration not only underscores the importance of EOSCU in advancing patient safety but also deepens our understanding of the science behind its effectiveness. We are proud to contribute to the health and safety of those who have served our country and remain committed to delivering solutions that make a measurable impact for patients nation-wide."

Key Findings:

Copper-impregnated EOSCU bedrail and table surfaces achieved a 97.3% and 96.8% reduction in C. difficile spores, respectively, after four hours of contact.

Even in the presence of organic material, which can impede antimicrobial efficacy, EOSCU surfaces showed over 91% spore reduction.

The study highlights EOSCU's continuous antimicrobial activity, addressing gaps in traditional cleaning methods that have been proven to be inadequate in eradicating C. difficile spores.

Why This Matters:

Healthcare-associated infections pose a major challenge to hospitals worldwide, increasing patient mortality, length of stay, and healthcare costs. C. difficile spores, in particular, are highly resilient and capable of surviving on hospital surfaces for months and resisting many hospital-grade disinfectants. C. difficile infections (CDIs) are life-threatening and are the leading cause of HAIs among hospitalized patients.

This study underscores how to overcome some of the limitations of current decontamination methods, such as chemical disinfectants and "no-touch" technologies, which are episodic and do not provide continuous disinfection like EOSCU.

Applications and Future Research:

The study provides compelling evidence for integrating copper-impregnated EOSCU into high-touch patient areas, such as bedrails and overbed tables, in healthcare facilities. The research team also highlighted the need for further exploration into the long-term impact of copper-impregnated surfaces on infection rates and their cost-effectiveness as part of infection control strategies.

What Experts Say:

"A major problem with standard practice for prevention of C.difficile infection is the reliance on daily or terminal disinfection protocols. The spread of C.difficele spores however can be direct contact or aerosolization of spores (e.g. by toilet flushing) and thereby potentially spread to a broad area thereby not influenced by the standard disinfection protocols, with the related infection risks. Although the treatment of C.difficele infection and disinfection has shown considerable progress in risk reduction, these approaches remain unfortunately inadequate, given the scope and consequences of infection. This copper technology is the first of a kind targeting hard surface area exposures, to replace a reactive with a proactive and extremely effective approach. The clinical implications and values are potentially limitless both for patient outcomes as well as overall healthcare system cost savings. Notably, this was a study funded by the National Institute of Health, further highlighting the high-level scientific interest and support of this exciting technology." Internationally-known gastroenterologist, Dr. David A Johnson MD MACG FASGE MVGS MACP, Professor of Medicine/Chief of Gastroenterology, Eastern VA Medical School/Old Dominion University (Not associated with the study.)

About the Study:

The research, titled "Efficacy of Copper-Impregnated Antimicrobial Surfaces Against Clostridioides difficile Spores," was conducted by the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System's Temple, TX. The full article is available through Cambridge University Press at .

About EOSCU:

EOSCU is manufactured in the United States using a patented process to incorporate varying levels of Cu into different preventive biocidal polymer matrixes. EOSCU is available in traditional design and build materials such as horizontal solid surfaces and bowls, and other resin-based products such as hospital bed rails, grab bars, and other high touch surfaces. EOSCU is based and manufactured in Norfolk VA.

Media Contact:

Erica Mitchell

EOS Surfaces

[email protected]

800-719-3671

SOURCE EOS Surfaces, LLC

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

Clinical Result

11 Dec 2024

VANCOUVER, British Columbia & DALLAS--(

BUSINESS WIRE

)--Alpha Cognition Inc. (Nasdaq: ACOG) (CSE: ACOG) (“Alpha Cognition” [ACI], or the “Company”), a biopharmaceutical company developing novel therapies for debilitating neurodegenerative disorders, today announced interim preclinical data that supports the continued development of ALPHA-1062 for the treatment of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). The interim data provides evidence of benefit for ALPHA-1062, in the treatment of mTBI resulting from repetitive blast trauma, a highly relevant military injury. Blast caused mTBI is considered to be the signature injury effecting soldiers where brain injury from explosive devices and artillery fire blast exposure is highly prevalent.

ACI previously documented extensive functional and neuropathological protection, provided by ALPHA-1062 administration, following a single moderate traumatic brain injury. This second pre-clinical study in a rodent model, supported by the US Department of Defense (DOD), is a collaboration with investigators at the Seattle Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Research (affiliated with both the University of Washington and the Veterans Administration). The study is ongoing, with interim data demonstrating that ALPHA-1062 administration following 3 consecutive days of blast induced mTBI, results in a reduction of TBI associated neuropathology.

Key findings demonstrated that, ALPHA-1062 administration reduced levels of neuroinflammation markers and neuropathology that occurs after blast trauma. High dose ALPHA-1062 reduced the levels of myeloid cell activation [CD 68] across multiple brain regions one month after blast. High dose ALPHA-1062 also demonstrated the ability to reduce midbrain astrogliosis [GFAP]. Astrogliosis is a process where brain cells called astrocytes become larger, multiply, and change in response to injury or disease in the brain. “These outcomes indicate a protective effect of ALPHA-1062, and demonstrated a reduction of neuropathology. The data provide further support for the continued development of ALPHA-1062 for the treatment of acute mild traumatic brain injury,” said Denis Kay, ACI’s Chief Scientific Officer. Further analysis of neuropathology and neurobehavioral [functional recovery] data is ongoing with the final study report due Q2/2025.

About Alpha Cognition Inc.

Alpha Cognition Inc. is a clinical stage, biopharmaceutical company dedicated to developing treatments for patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Cognitive Impairment with mild Traumatic Brain Injury (“mTBI”), for which there are currently no approved treatment options.

ALPHA-1062, is a patented new chemical entity being developed as a new generation acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, with expected minimal gastrointestinal side effects. ALPHA-1062’s active metabolite is differentiated from donepezil and rivastigmine in that it binds neuronal nicotinic receptors, most notably the alpha-7 subtype, which is known to have a positive effect on cognition. ALPHA-1062 is also being developed in combination with memantine to treat moderate to severe Alzheimer’s dementia.

An intranasal formulation of ALPHA-1062 has demonstrated potent preservation brain structure and function in a preclinical model of moderate TBI, where enhanced recovery from the brain injury was also seen. The intranasal formulation is currently being evaluated for its ability to provide protection from a military relevant model of repeated mild TBI, in a program sponsored by the US Department of Defense.

Neither Canadian Securities Exchange (the “CSE”) or the OTC Markets Group, accepts responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this release.

Forward-looking Statements

This news release includes forward-looking statements within the meaning of applicable securities laws. Except for statements of historical fact, any information contained in this news release may be a forward‐looking statement that reflects the Company’s current views about future events and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties, assumptions and other factors that may cause the actual results, levels of activity, performance or achievements to be materially different from the information expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. In some cases, you can identify forward‐looking statements by the words “may,” “might,” “will,” “could,” “would,” “should,” “expect,” “intend,” “plan,” “objective,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “project,” “potential,” “target,” “seek,” “contemplate,” “continue” and “ongoing,” or the negative of these terms, or other comparable terminology intended to identify statements about the future. Forward‐looking statements may include statements regarding the TBI out-licensing plan and associated financing, the availability of funding pursuant to financings, the Company’s business strategy, market size, potential growth opportunities, capital requirements, clinical development activities, the timing and results of clinical trials, regulatory submissions, potential regulatory approval and commercialization of the Company’s products. Although the Company believes to have a reasonable basis for each forward-looking statement, we caution you that these statements are based on a combination of facts and factors currently known by us and our expectations of the future, about which we cannot be certain. The Company cannot assure that the actual results will be consistent with these forward-looking statements. These forward‐looking statements speak only as of the date of this news release and the Company undertakes no obligation to revise or update any forward‐looking statements for any reason, even if new information becomes available in the future.

100 Deals associated with Veterans Administration Medical Center

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Veterans Administration Medical Center

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 10 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Preclinical

1

2

Other

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Docosahexaenoic acid | Coronary Disease More | Preclinical |

PD-117596 ( Bacterial DNA gyrase ) | Bacterial Infections More | Pending |

BL-P2090 ( β-lactamase ) | Tuberculosis More | Pending |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

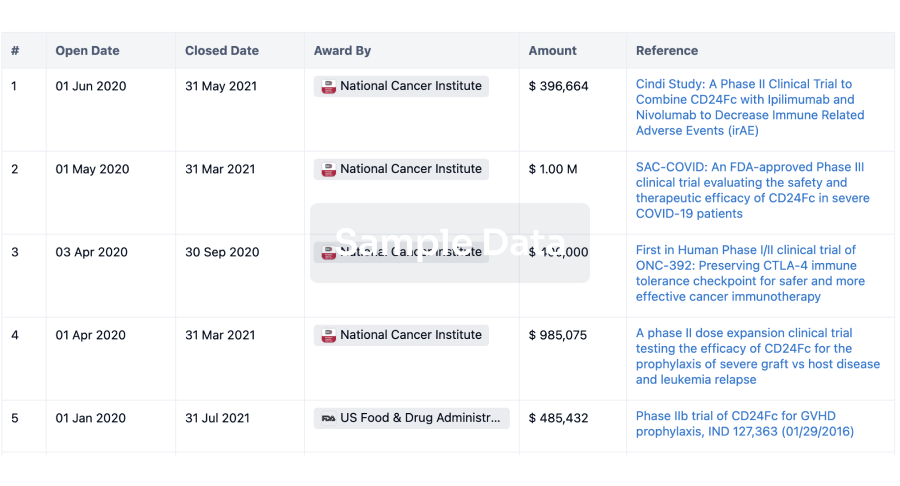

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free