Request Demo

Last update 17 Feb 2026

Neutrolis, Inc.

Last update 17 Feb 2026

Overview

Tags

Skin and Musculoskeletal Diseases

Immune System Diseases

Other Diseases

Enzyme

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Disease Domain | Count |

|---|---|

| Immune System Diseases | 1 |

| Infectious Diseases | 1 |

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Enzyme | 4 |

Related

4

Drugs associated with Neutrolis, Inc.Target- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 1 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 1 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

3

Clinical Trials associated with Neutrolis, Inc.NCT07237659

A Phase 1a/b, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Safety of NTR-1011 in Healthy Adults and Adult Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

This phase 1a and 1b study is designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, immunogenicity, and preliminary efficacy of NTR-1011 in healthy adults and in adult patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. The main goals of this study are to determine the safety profile of NTR-1011 across subcutaneous and intravenous dose levels, understand how the drug behaves in the body, characterize its biological activity through relevant pharmacodynamic markers, assess the potential for immune responses to treatment, and explore early signals of clinical benefit in autoimmune disease settings.

This is a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study that begins with a single ascending dose evaluation in healthy volunteers followed by a multiple dose assessment in patients. The design is intended to define the highest safe and well tolerated dose, establish a robust PK and PD baseline, and generate initial patient level evidence to support dose selection and advancement into subsequent clinical development.

This is a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study that begins with a single ascending dose evaluation in healthy volunteers followed by a multiple dose assessment in patients. The design is intended to define the highest safe and well tolerated dose, establish a robust PK and PD baseline, and generate initial patient level evidence to support dose selection and advancement into subsequent clinical development.

Start Date04 Sep 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

CTIS2024-512196-12-00

A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, single-ascending-dose, Phase 1a/b study to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity of intravenous NTR-641 in healthy adults and patients with acute ischemic stroke

Start Date14 Oct 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT04941183

A Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind, Single-ascending-dose and Multiple-ascending-dose, Phase 1 Study to Assess the Safety and Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Immunogenicity of IV NTR-441 Solution in HV Adults and COVID-19 Patients

This first-in-human clinical study is a Phase 1a/ 1b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the safety, tolerability, and PK/PD of NTR-441 in healthy subjects and patients with COVID-19 after single ascending IV infusion doses and multiple ascending IV infusion doses.

Start Date14 Apr 2021 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Neutrolis, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Neutrolis, Inc.

Login to view more data

1

Literatures (Medical) associated with Neutrolis, Inc.Frontiers in immunology

Targeting NETs using dual-active DNase1 variants

Article

Author: Wolska, Nina ; Khong, Danika ; Butler, Lynn M ; Gerwers, Julian C ; Mailer, Reiner K ; Fuchs, Tobias A ; Maas, Coen ; Omidi, Maryam ; Preston, Roger J S ; Renné, Thomas ; Göbel, Josephine ; Odeberg, Jacob ; Stavrou, Evi X ; Englert, Hanna ; Frye, Maike ; Beerens, Manu ; Konrath, Sandra

Background:

Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) are key mediators of immunothrombotic mechanisms and defective clearance of NETs from the circulation underlies an array of thrombotic, inflammatory, infectious, and autoimmune diseases. Efficient NET degradation depends on the combined activity of two distinct DNases, DNase1 and DNase1-like 3 (DNase1L3) that preferentially digest double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and chromatin, respectively.

Methods:

Here, we engineered a dual-active DNase with combined DNase1 and DNase1L3 activities and characterized the enzyme for its NET degrading potential in vitro. Furthermore, we produced a mouse model with transgenic expression of the dual-active DNase and analyzed body fluids of these animals for DNase1 and DNase 1L3 activities. We systematically substituted 20 amino acid stretches in DNase1 that were not conserved among DNase1 and DNase1L3 with homologous DNase1L3 sequences.

Results:

We found that the ability of DNase1L3 to degrade chromatin is embedded into three discrete areas of the enzyme's core body, not the C-terminal domain as suggested by the state-of-the-art. Further, combined transfer of the aforementioned areas of DNase1L3 to DNase1 generated a dual-active DNase1 enzyme with additional chromatin degrading activity. The dual-active DNase1 mutant was superior to native DNase1 and DNase1L3 in degrading dsDNA and chromatin, respectively. Transgenic expression of the dual-active DNase1 mutant in hepatocytes of mice lacking endogenous DNases revealed that the engineered enzyme was stable in the circulation, released into serum and filtered to the bile but not into the urine.

Conclusion:

Therefore, the dual-active DNase1 mutant is a promising tool for neutralization of DNA and NETs with potential therapeutic applications for interference with thromboinflammatory disease states.

5

News (Medical) associated with Neutrolis, Inc.01 Nov 2025

Welcome back to Endpoints Weekly, and welcome to November. This week kicked off with quarterly earnings results from a handful of companies, including Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis and Bristol Myers Squibb. Then on Thursday, Novo Nordisk made waves when it announced that it submitted an unsolicited bid for the obesity biotech Metsera, a month after Pfizer disclosed its plans to acquire it. The Endpoints team is following the saga closely, so stay tuned for more details.

Novartis also made headlines this week for its $12 billion offer to buy out a neuromuscular drug developer. And Ryan Cross has an exclusive on a low-profile biotech targeting one of the immune system’s natural defenses to potentially treat autoimmune disease.

We’ll have reporters covering earnings results next week from Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Moderna and more. Until then, have a great weekend! —

Nicole DeFeudis

🤼 Novo Nordisk shocked the industry this week

by announcing it made

an unsolicited bid

for obesity biotech Metsera for $6.5 billion upfront. Pfizer, which had announced its intent to buy out Metsera last month for $4.9 billion upfront, almost immediately came out swinging, saying Novo’s bid was “in violation” of antitrust law. This is going to be one of those stories where things can change quickly — evidenced by Pfizer

suing Metsera and Novo

late Friday — and we’ll have you covered from every angle.

From Novo’s side, the bid comes ahead of new CEO

Maziar Mike Doustdar’s

first earnings call next week. The Danish drugmaker has been in the midst of “turning the [bleeping] tanker,” as Logan Roy from HBO’s “Succession” would say. As Elizabeth Cairns and Kyle LaHucik

wrote earlier this week

, Novo has faced significant pressure from GLP-1 competitor Eli Lilly, laying off thousands of staffers and cutting back on pipeline projects. But with this week’s Metsera offer, Doustdar appears to be

chasing the deals his predecessors wouldn’t

, Liz writes.

For Pfizer, analysts say CEO Albert Bourla could be leveraging

his relationship with President Donald Trump, with a company statement emphasizing the anticompetitive nature of the bid by letting Novo Nordisk take over “an emerging American challenger.” The stakes for Pfizer are high, as it dropped an oral GLP-1 called danuglipron when it caused intolerable liver side effects in one patient earlier this year. The back-and-forth will also

pose a test to Trump’s FTC

, Jared Whitlock writes.

Metsera, meanwhile, appears content to let Novo and Pfizer

duke it out to try to drive up the price. The biotech also put out a statement this week that said it views Novo’s offer as a “superior proposal,” which would legally give Pfizer until Nov. 4 to submit a counterbid. But Pfizer noted in its own statement that the Novo offer is “illusory and cannot qualify as a superior proposal” and subsequently sued to enforce the transaction.

What’s next in this unfolding saga?

Kyle LaHucik takes a look at

six burning questions

going forward, while Elizabeth Cairns asks

what Metsera might bring to Novo

. We also broke down the news on

an emergency session of Post-Hoc Live

, where Kyle and Drew Armstrong chatted with analyst Evan Seigerman. Pfizer is expected to report its third-quarter earnings on Nov. 4.

💰 Novartis

has offered

about $12 billion to acquire Avidity Biosciences,

a neuromuscular drugmaker that’s months away from submitting its lead candidate to the FDA. It’s the second-largest deal announcement of the year. But Novartis

CEO Vas Narasimhan said

during the company’s third-quarter earnings call on Thursday that the deal could have been “twice as big” if they had waited for a Phase 3 readout, which is expected to come next year.

“In our view, the phase-appropriate risk was reasonable given the data that we’ve seen,” Narasimhan said.

Novartis is getting three candidates in late-stage testing

for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), and myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1). Meanwhile, Avidity plans to spin out its early-stage R&D work in precision cardiology into a separate company that will maintain partnerships with Bristol Myers Squibb and Eli Lilly.

The spinout will be led by Avidity’s current chief program officer Kathleen Gallagher.

The new company will be publicly traded and get $270 million in cash to support its pipeline.

📊 Biopharma companies are diving headfirst into earnings season,

with several big names reporting third-quarter results this week. Here are some of the highlights:

🧬 A new startup called Neutrolis

is taking a look at how one of the strangest ways the immune system defends our bodies from invaders can be leveraged to create new drugs. Ryan Cross took

an in-depth look at this process

that involves neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs, as Neutrolis has put together more than $50 million in seed and Series A financing.

Along with the funding, Neutrolis put out data

this week from a Phase 1 study, showing the drug can quickly chop up NETs and potentially help those with autoimmune disorders get a “reset.”

Most promising was the data from one patient.

Within six hours of infusing him with the treatment, more than 80% of the rashes that covered him from head to toe were cleared, arthritis in multiple joints was resolved, and inflammation in his eyes was reduced.

✅ BridgeBio touted multiple late-stage wins this week,

including in a rare disease called limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2I/R9. At the

study’s interim analysis,

BridgeBio’s drug BBP-418 showed a positive result on a specific protein that was originally expected to be used as a surrogate endpoint to seek accelerated approval. But because BBP-418 also hit statistical significance on multiple endpoints, BridgeBio will now ask the FDA whether there is a path to full approval.

In another study, BridgeBio’s oral drug encaleret hit the primary endpoint

for a genetic thyroid disorder called autosomal dominant hypocalcemia type 1, or ADH1. Based on the data, the biotech said it plans to file for full FDA approval in the first half of next year. Read more from Max Gelman

here

.

AcquisitionClinical ResultPhase 1

29 Oct 2025

Of the immune system’s many defenses, neutrophils may have one of the strangest. The cells eject their DNA to enmesh bacterial invaders in spiderweb-like tangles called neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs. But making too many of these cobwebs, or not clearing them quickly enough, can exacerbate autoimmune diseases.

Now, a startup that’s kept a low profile since its founding eight years ago is emerging with a new way to solve that problem. Neutrolis has developed a drug based on a DNA-chopping enzyme and has conducted the first clinical test, suggesting that directly targeting and sweeping up NETs may provide a new way to treat conditions like arthritis and lupus.

In an interview with

Endpoints News

, the company said it has finished testing its enzyme therapy in a 51-person Phase 1 safety study that demonstrated the drug’s ability to quickly chop up NETs. But the most dramatic evidence of the drug’s potential came from a single patient whose symptoms were reduced within hours of receiving the therapy through an expanded access program.

The 17-year-old boy was born without an enzyme called DNASE1L3, which is the body’s natural way of removing NETs. Neutrolis uses a modified version of the enzyme in its drug, and within 6 hours of infusing him with the treatment, more than 80% of the rashes that covered him from head to toe were cleared, arthritis in multiple joints resolved and inflammation in his eyes was reduced.

“I’ve practiced rheumatology for over 30 years. And I have never seen anything like this before in my life,” Neutrolis’ Chief Medical Officer Andreas Reiff told Endpoints.

The company is presenting the data at ACR Convergence, the American College of Rheumatology’s annual meeting, in Chicago on Wednesday.

The boy had to stop receiving weekly infusions of the drug after 3 months because he developed an immune reaction to the enzyme. Neutrolis has since developed a new version of its drug, and the company plans to start a pair of Phase 2a studies in patients with arthritis and lupus in the first half of 2026.

Neutrolis was co-founded by immunologists Tobias Fox and Abdul Hakkin in 2017, both of whom have studied NETs for nearly two decades.

The Cambridge, MA-based startup has a small team of about 10 people. CEO Anthony Aiudi said that the company has raised more than $50 million in seed and Series A funding, mostly from Morningside Capital, where he was an investor before becoming Neutrolis’ CEO in June.

Neutrophils are the most abundant immune cells in the body, and a relatively obscure but growing body of research suggests that some people make antibodies that attack NETs, which can trigger more inflammation, which then triggers the release of more NETs in a vicious cycle that fuels autoimmune disease.

“As with so many immune mechanisms, what is beneficial on one side can do a lot of harm if it’s uncontrolled,” Fox said, who is also chief scientific officer of Neutrolis. “The very same mechanisms that kill bacteria can also kill our own cells.”

Neutrolis’ mid-stage studies will focus on systemic lupus erythematosus patients who make autoantibodies against double-stranded DNA — what NETs are made of — and in rheumatoid arthritis patients who make autoantibodies against a protein called ACPA, which is found in NETs.

Aiudi said the company is about to begin fundraising for a Series B round of roughly $60 million, which would provide the startup with 24 to 30 months of runway to complete these studies.

The company’s first therapy, called NTL-441, is made from the DNASE1L3 enzyme fused to the plasma protein albumin to improve the drug’s half-life. The enzyme chops NETs into smaller fragments, which the company can measure as a biomarker to see if the drug is working.

Neutrolis first tested multiple dose levels of the drug in 35 healthy volunteers without NETs. The company then tested the drug in 16 patients hospitalized with Covid-19 who had a “high NET burden” that can cause immunothrombosis.

In Covid-19 patients, the drug increased DNA biomarkers, suggesting the enzyme chopped up excess NETs, but its benefits were unclear. Fox said the company saw “signals” of efficacy but “nothing statistically significant due to the heterogeneity of the patient population.”

The patient with the DNASE1L3 deficiency offered a more direct way to test the potential efficacy of the therapy. Despite a heavy regimen of immunosuppressants, the boy still had many uncontrolled symptoms, and his rheumatologist was considering a bone marrow transplant before learning about Neutrolis’ treatment.

Within hours of infusing the drug, the patient’s arthritis, eye redness and rash were all reduced. Common measures of inflammation — such as complement proteins and cytokines — didn’t coincide with the patient’s improvement, but a spike in bits of broken-down NETs did.

“This is, in our view, the very first time to validate NETs as a foundational driver of disease,” Fox said. “I still get goosebumps today.”

The patient, who had never been exposed to DNASE1L3 before, developed anti-drug antibodies to the enzyme and stopped receiving it about five months ago. Some symptoms have returned, but his joint inflammation and swelling haven’t recurred, Reiff said.

Three other people in the Phase 1 study also developed high levels of antibody-drug antibodies to the linker between the DNASE1L3 enzyme and albumin. The company has made a second-generation drug called NTR-1011 that it hopes will solve that problem. It is currently in a Phase 1 study.

Going forward, Neutrolis is focusing on more common conditions, where it hopes an initial burst of its therapy will clear out excess NETs, and chronic treatment will keep further buildup at bay. “Rather than suppressing the immune system, we’re finding a way to reset it,” Aiudi said

Phase 1Immunotherapy

02 Jan 2025

Dec. 23, 2024 -- Neutrolis Inc., a clinical stage biotech company focused on targeting Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, today announced that it has entered into an exclusive licensing agreement with the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC). Under the agreement, Neutrolis has acquired the rights to intellectual property that covers the use of topical DNase enzymes in the eye. Neutrolis is developing L304, a novel DNase generated using its proprietary exDNASE™ platform, to target Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) as a potential treatment for dry eye disease (DED).

The basis of the issued patent stems from the pioneering basic and clinical research work in the use of topical DNase conducted by Sandeep Jain, M.D., BA Field Professor of Ophthalmology and Director of Dry Eye and Ocular Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD) Clinic at Department of Ophthalmology, UIC College of Medicine, and an advisor to Neutrolis. Two recently completed early phase clinical trials led by Dr. Jain, funded in part by grants from the National Eye Institute/NIH and Research to Prevent Blindness, established the feasibility of DNase therapies in moderate to severe DED and in ocular GvHD. Neutrolis plans to leverage this licensed patent and the learnings from the clinical studies to advance its proprietary L304 program in moderate to severe DED.

“It is clear that NETs contribute to DED and this licensing agreement represents an important step in bringing our innovative treatments to patients who live with the daily challenges of DED,” said Toby Fox, Ph.D., co-founder and chief executive officer of Neutrolis.

“Our work demonstrates that NETs have an underlying role in DED and I am delighted to be working in an advisory capacity with Neutrolis, a company leading the field of NET-based disease biology and dedicated to transforming inflammatory and autoimmune disease treatment with their novel approach,” said Dr. Jain. “There is a need for new therapies that have the potential to redefine the standard of care for patients with moderate to severe dry eye disease.”

“Dr. Jain and his team have laid the groundwork for the use of topical DNase in the eye as a treatment for DED that results from inflammation,” said Abdul Hakkim, Ph.D., chief operating officer and co-founder, Neutrolis. “His research and clinical experience provide additional valuable support for the further development of L304.”

DED occurs when the eyes fail to produce adequate tears or when the tears produced are not effective in maintaining eye moisture. This condition can lead to discomfort and, in some cases, vision problems. Autoimmune disorders like Sjögren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and ocular graft-versus-host disease can worsen dry eye symptoms. Approximately one-third of patients visiting ophthalmology clinics report dry eye symptoms, making it a prevalent issue in eye care. It affects millions of people annually, particularly older adults and women. DED represents the third largest segment within the ophthalmology market. The global market for dry eye treatments is projected to exceed USD 6.5 billion by 2027.

Neutrolis is revolutionizing the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases by developing first-in-class, non-immunosuppressive therapies that target Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs). NETs are web-like structures composed of DNA, histones and antimicrobial proteins released by neutrophils that can lead to tissue damage and chronic inflammation and play a critical role in the progression of immune-mediated inflammatory disorders. The extracellular DNA and proteins within NETs trigger autoantibodies, fueling flares in these conditions. The company’s exDNASE™ platform powers the development of analogs of naturally occurring enzymes that disassemble NETs. By addressing the underlying cause of NET-driven diseases, such as lupus, dry eye disease, and other chronic autoimmune conditions, Neutrolis aims to advance transformational therapies for patients. For more information, please visit neutrolis.com.

The content above comes from the network. if any infringement, please contact us to modify.

License out/in

100 Deals associated with Neutrolis, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Neutrolis, Inc.

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 18 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Preclinical

2

2

Phase 1

Other

7

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

NTR-1011 | Rheumatoid Arthritis More | Phase 1 |

L304 | Ocular inflammation More | Preclinical |

NTR-L301 | Skin Diseases More | Discontinued |

NTR-441 ( LEKTI ) | COVID-19 More | Discontinued |

NTR-452 ( LEKTI ) | Autoimmune Diseases More | Discontinued |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

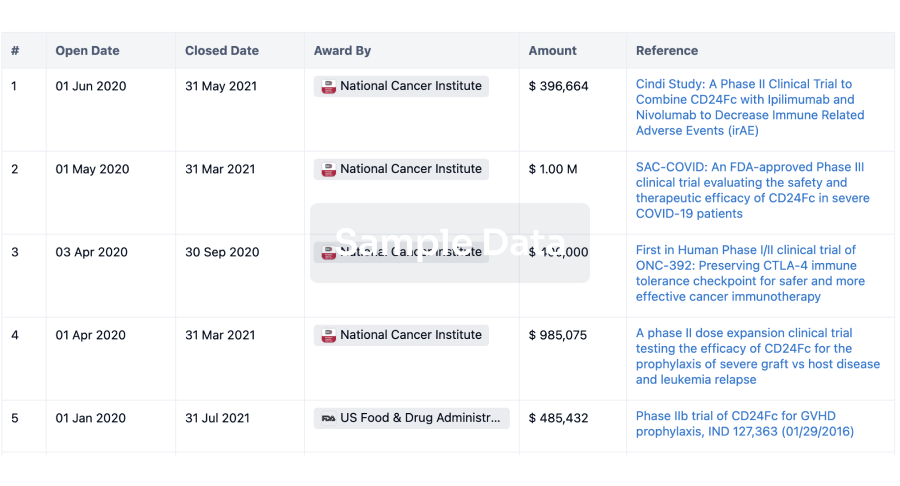

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free