Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

NCOR2

Last update 08 May 2025

Basic Info

Synonyms CTG repeat protein 26, CTG26, N-CoR2 + [11] |

Introduction Transcriptional corepressor that mediates the transcriptional repression activity of some nuclear receptors by promoting chromatin condensation, thus preventing access of the basal transcription (PubMed:10077563, PubMed:10097068, PubMed:18212045, PubMed:20812024, PubMed:22230954, PubMed:23911289). Acts by recruiting chromatin modifiers, such as histone deacetylases HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 (PubMed:22230954). Required to activate the histone deacetylase activity of HDAC3 (PubMed:22230954). Involved in the regulation BCL6-dependent of the germinal center (GC) reactions, mainly through the control of the GC B-cells proliferation and survival (PubMed:18212045, PubMed:23911289). Recruited by ZBTB7A to the androgen response elements/ARE on target genes, negatively regulates androgen receptor signaling and androgen-induced cell proliferation (PubMed:20812024).

Isoform 1 and isoform 4 have different affinities for different nuclear receptors.

Isoform 1 and isoform 4 have different affinities for different nuclear receptors. |

Related

1

Drugs associated with NCOR2Target |

Mechanism NCOR2 inhibitors |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest Phase- |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date20 Jan 1800 |

100 Clinical Results associated with NCOR2

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with NCOR2

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with NCOR2

Login to view more data

912

Literatures (Medical) associated with NCOR201 Jun 2025·European Journal of Nutrition

Vitamin D deficiency promotes intervertebral disc degeneration via p38/NCoR2-mediated extracellular matrix degradation

Article

Author: Chen, Chao ; Wang, Bing ; He, Qicong ; Wang, Xuenan ; Zhan, Enyu ; Li, Xingguo ; Hu, Yaoquan ; Lv, Zhengpin ; Zhang, Fan

01 Apr 2025·Human Pathology

Hydroa vacciniforme lymphoproliferative disorder, a clinicopathologic and genetic analysis

Article

Author: Zhang, Weiwei ; Molina-Kirsch, Hernan ; Postigo, Mauricio ; Chan, Wing C ; Nakunam, Yasodha ; Beltran, Brady ; Medina, Ivan Maza ; Song, Joo Y ; Saleem, Atif ; Vasquez, Liliana ; Pupwe, George

04 Mar 2025·Hemoglobin

Molecular Characterization of Complex Thalassemia with Multiple Variants in β-Globin Gene Cluster and the Identification of a Novel Structural Rearrangement in γ-Globin Gene

Article

Author: Zhou, Jihui ; Liu, Yanqiu ; Huang, Ting ; Shao, Junhui ; Luo, Haiyan ; Fang, Yuan ; Ma, Pengpeng ; Zou, Yongyi ; Yang, Bicheng ; Xu, Yonghua ; Yang, Yan

2

News (Medical) associated with NCOR222 Feb 2024

The drug works by targeting a component of the process that turns sperm stem cells into sperm.

A drug with a past life as a potential anti-cancer agent might someday have a new job as "the pill" for men, new data in mice suggest.

In a journal article published Feb. 20 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers at the Salk Institute explained how they discovered that an oral HDAC inhibitor called entinostat acts like an “off-on” switch for sperm creation that keeps male mice from reproducing without any effect on their libido. Within 60 to 90 days of stopping the pill, the mice were able to impregnate female animals again without any harm to the resulting offspring.

Effective male contraceptives are a long time coming, senior author Ronald Evans, Ph.D., told Fierce Biotech Research in an interview. Researchers have been trying for decades to develop a noninvasive, reversible, easily accessible drug candidate that is as effective as the birth control pill is for women, with no success so far.

“Our game-changing or transformative results are that it’s now possible to have a male equivalent of the pill that’s able to give men control as well, without having to rely on condoms,” Evans said. (Of course, this wouldn’t eliminate the need for condoms—they’re still necessary to protect against some types of sexually transmitted disease.)

Sperm production is a complex process with many components, a limiting factor in coming up with drugs to block it. Hormonal candidates, such as the drug DMAU, have mainly focused on blocking testosterone—a route that varies in effectiveness depending on the patient population and can come with side effects. A non-hormonal injectable drug called RISUG is making its way through clinical trials in India, and a version called Vasalgel is in development in the U.S. However, both of these require either an injection or an in-office procedure.

One non-hormonal mechanism that scientists have long considered is blocking receptors for retinoic acid, a form of vitamin A that is critical to the process whereby sperm stem cells differentiate into fully functional sperm. But while this does stop sperm production in mice and rats, it comes at a cost: Retinoic acid is needed for a wide range of processes throughout the body, so inhibiting its activity systemically can lead to serious side effects, Evans explained.

“You can kind of get it to work the way you want, but it’s not specific enough to be a useful way to address the challenge of controlling spermatogenesis,” he said. Researchers have largely abandoned the effort in favor of other approaches.

But in the new study, Evans’ lab—which was the first to clone the receptor for retinoic acid—learned that there’s another way to go about blocking its role in sperm production without systemic effects. While studying a gene regulatory factor called SMRT, one of the researchers in his lab pointed out that it was part of a complex of proteins that were involved in regulating retinoic acid receptors in sperm creation.

“He suggested that maybe we should actually not target the retinoic acid receptor itself, but target SMRT,” Evans recalled. Not only would doing so be easier than targeting the receptor directly, but it would also be safer because the target’s systemic effects are more limited, he added.

This led the team to see if blocking SMRT with entinostat, which Evans co-developed under his former company Syndax, would be a solution, as SMRT’s function is controlled by the same components that are interrupted by HDAC inhibitors. They gave male mice one of three different doses of the drug once a day for 60 days, then tested their ability to mate. They also tested whether taking mice off the drug would restore sperm production—and whether it would affect the health of their offspring.

To their surprise, the approach was a success.

“[The researcher] came back and said, ‘It really works.’ I said, ‘What do you mean it really works?’” Evans recalled. “He said, ‘It’s a total contraceptive. The mice’s libido is totally normal. And if you take it away, [their ability to reproduce] comes back.’”

None of the mice that were on the drug sired offspring during the treatment period, compared to litters of around 10 pups each from control males. Sixty days after stopping the treatment, mice in the experimental groups were able to impregnate females again to the same degree as controls. All of the pups were born healthy.

During the treatment period, the researchers noticed that the animals’ testis size was “dose-dependently reduced” as their sperm production capacity fell. This was mostly recovered after 60 days off the drug, figures in the article showed. There were no other discernible side effects, such as weight loss that would indicate a change in testosterone levels, the researchers wrote in their paper.

“As a proof of principle, our findings indicate that chronic, oral administration of MS-275 transiently blocks male fertility without permanently affecting reproductive capacity or the genomic integrity of sperm,” they wrote.

Evans now hopes to test entinostat as a male contraceptive in larger animals and eventually in humans. The drug already has FDA breakthrough status for advanced breast cancer and has been studied in clinical trials for pancreatic cancer, brain cancer, melanoma and other cancers, so safety in humans has already been established, he said.

Given the results, Evans’ team has no plans to look at whether other HDAC inhibitors have birth control potential as well, he said, though they might look at other medical uses for entinostat. But for now, its use as a male contraceptive “is at the top of the list,” he said.

“That’s where we want to focus and see if there is a company that wants to actually develop this. Or do we have to start our own?” Evans, a serial biotech entrepreneur, said. “That’s kind of fun to think about.”

Clinical Result

20 Feb 2024

Scientists discovered a new target for reversible, non-hormonal male birth control. The drug, an HDAC inhibitor, blocked sperm production and fertility in male mice without affecting libido or future reproduction.

Surveys show most men in the United States are interested in using male contraceptives, yet their options remain limited to unreliable condoms or invasive vasectomies. Recent attempts to develop drugs that block sperm production, maturation, or fertilization have had limited success, providing incomplete protection or severe side effects. New approaches to male contraception are needed, but because sperm development is so complex, researchers have struggled to identify parts of the process that can be safely and effectively tinkered with.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have found a new method of interrupting sperm production, which is both non-hormonal and reversible. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on February 20, 2024, implicates a new protein complex in regulating gene expression during sperm production. The researchers demonstrate that treating male mice with an existing class of drugs, called HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitors, can interrupt the function of this protein complex and block fertility without affecting libido.

"Most experimental male birth control drugs use a hammer approach to blocking sperm production, but ours is much more subtle," says senior author Ronald Evans, professor, director of the Gene Expression Laboratory, and March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology at Salk. "This makes it a promising therapeutic approach, which we hope to see in development for human clinical trials soon."

The human body produces several million new sperm per day. To do this, sperm stem cells in the testes continuously make more of themselves, until a signal tells them it's time to turn into sperm -- a process called spermatogenesis. This signal comes in the form of retinoic acid, a product of vitamin A. Pulses of retinoic acid bind to retinoic acid receptors in the cells, and when the system is aligned just right, this initiates a complex genetic program that turns the stem cells into mature sperm.

Salk scientists found that for this to work, retinoic acid receptors must bind with a protein called SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors). SMRT then recruits HDACs, and this complex of proteins goes on to synchronize the expression of genes that produce sperm.

Previous groups have tried to stop sperm production by directly blocking retinoic acid or its receptor. But retinoic acid is important to multiple organ systems, so interrupting it throughout the body can lead to various side effects -- a reason many previous studies and trials have failed to produce a viable drug. Evans and his colleagues instead asked whether they could modulate one of the molecules downstream of retinoic acid to produce a more targeted effect.

The researchers first looked at a line of genetically engineered mice that had previously been developed in the lab, in which the SMRT protein was mutated and could no longer bind to retinoic acid receptors. Without this SMRT-retinoic acid receptor interaction, the mice were not able to produce mature sperm. However, they displayed normal testosterone levels and mounting behavior, indicating that their desire to mate was not affected.

To see whether they could replicate these genetic results with pharmacological intervention, the researchers treated normal mice with MS-275, an oral HDAC inhibitor with FDA breakthrough status. By blocking the activity of the SMRT-retinoic acid receptor-HDAC complex, the drug successfully stopped sperm production without producing obvious side effects.

Another remarkable thing also happened once the treatment was stopped: Within 60 days of going off the pill, the animals' fertility was completely restored, and all subsequent offspring were developmentally healthy.

The authors say their strategy of inhibiting molecules downstream of retinoic acid is key to achieving this reversibility.

Think of retinoic acid and the sperm-producing genes as two dancers in a waltz. Their rhythm and steps need to be coordinated with each other for the dance to work. But if you throw something in that makes the genes miss a step, the two are suddenly out of sync and the dance falls apart. In this case, the HDAC inhibitor causes the genes' misstep, halting the dance of sperm production.

However, if the dancer can find its footing and get back in step with its partner, the waltz can resume. In the same way, the authors say that removing the HDAC inhibitor allows the sperm-producing genes to get back in sync with the pulses of retinoic acid, turning sperm production back on as desired.

"It's all about timing," says co-author Michael Downes, a senior staff scientist in Evans' lab. "When we add the drug, the stem cells fall out of sync with the pulses of retinoic acid, and sperm production is halted, but as soon as we take the drug away, the stem cells can reestablish their coordination with retinoic acid and sperm production will start up again."

The authors say the drug doesn't damage the sperm stem cells or their genomic integrity. While the drug was present, the sperm stem cells simply continued regenerating as stem cells, and when the drug was later removed, the cells could regain their ability to differentiate into mature sperm.

"We weren't necessarily looking to develop male contraceptives when we discovered SMRT and generated this mouse line, but when we saw that their fertility was interrupted, we were able to follow the science and discover a potential therapeutic," says first author Suk-Hyun Hong, a staff researcher in Evans' lab. "It's a great example of how Salk's foundational biological research can lead to major translational impact."

Other authors include Glenda Castro, Dan Wang, Russell Nofsinger, Annette R. Atkins, and Ruth T. Yu of Salk, Maureen Kane, Alexandra Folias, and Joseph L. Napoli of UC Berkeley, Paolo Sassone-Corsiof UC Irvine, Dirk G. de Rooij of Utrecht University, and Christopher Liddle of the University of Sydney.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA265762 and CA220468) and the Next Generation Sequencing and Flow Cytometry Cores at Salk, funded by the Salk Cancer Center (NCI grant NIH-NCI CCSG: P30 014195).

Analysis

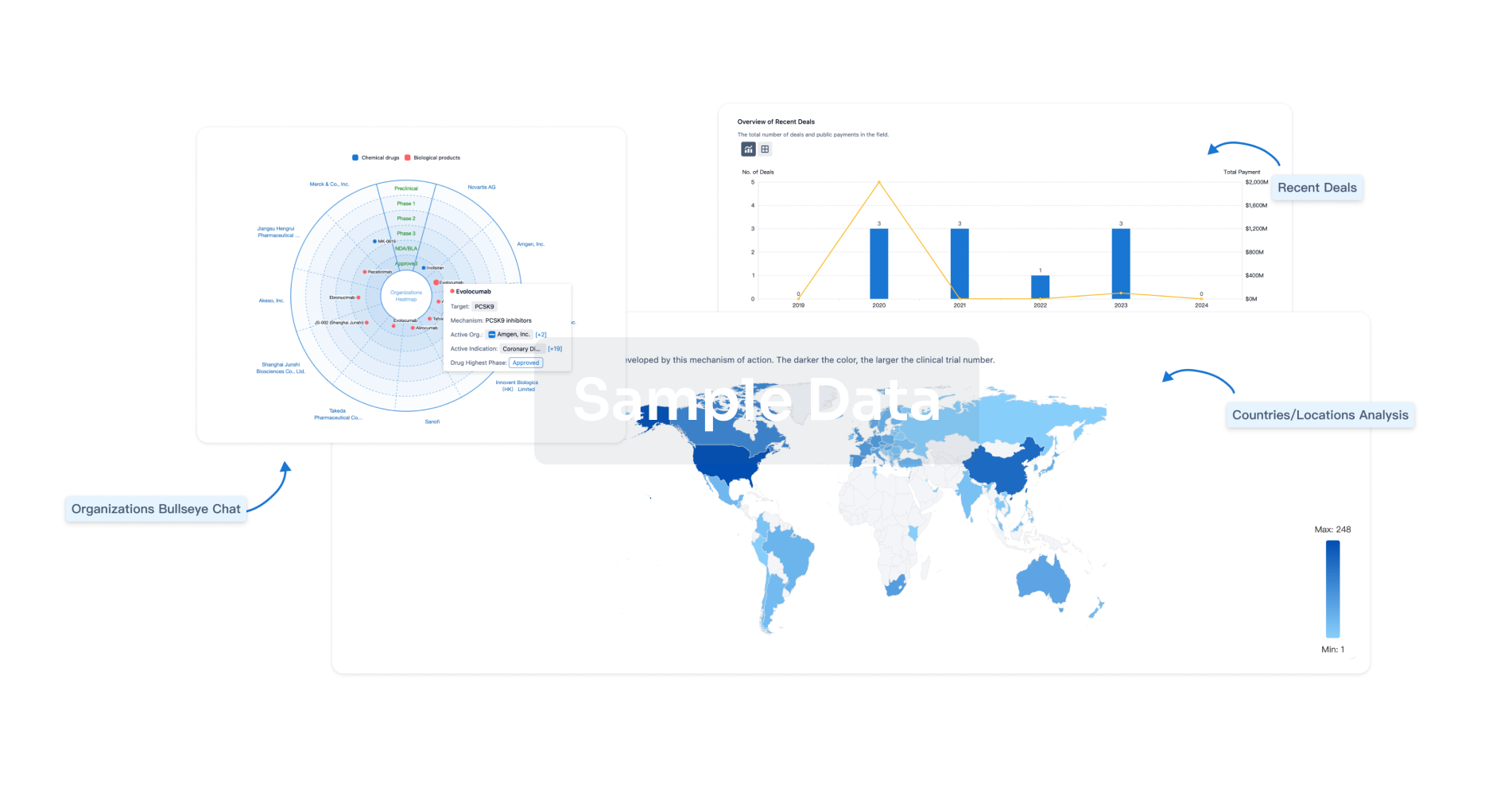

Perform a panoramic analysis of this field.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free